Mine to Market: The ‘Adventure Story’ of Colored Stones

February 12, 2016

When it comes to selling colored stones, a retailer’s supply-chain knowledge has tangible benefits at the counter – or wherever the point of sale happens to be.

That’s what Andy Lucas, GIA’s education manager of field gemology, and Dr. Tao Hsu, technical editor and research specialist for Gems & Gemology, told local GIA alumni and Women’s Jewelry Association members at GIA's Carlsbad campus on Jan. 13. Lucas and Hsu have traveled the world together to discover and document what happens as a gemstone travels from the mine to the market.

The allure of colored stones has not changed much over the centuries, Lucas said, so retailers need to share the romance and adventure.

“The people who are more knowledgeable about the story are better at making customers feel comfortable, at gaining their trust and at piquing their interest,” he said.

Lucas acknowledged that the details of that story have evolved over the years.

“People today have more access to information … they’re more interested in mining, about the art of cutting,” he said. “There are also a lot of ethical issues that come into play, and people are interested in hearing about them.”

One of the first things that they noticed on their expeditions is that the technology at a colored gem’s source ranges from the large-scale mines operated by capital-rich companies, to the smaller artisanal mines. Both types of operations can both “complement and conflict with each other.”

Hsu cited the Kagem Mine, a primary emerald mine in Zambia, as one of the best examples of modern mechanized, large-scale mining she's seen.

“I was amazed at the size of the pit,” she said. “Their primary production is from this pit that’s over a kilometer long. The explosion that’s involved, because this is hard-rock mining, is quite amazing to see − and to feel the shake of the ground.” Hsu said that Gemfields, which owns the mine, adheres to a strict, consistent grading system for its emeralds.

“People today have more access to information … they’re more interested in mining, about the art of cutting. There are also a lot of ethical issues that come into play, and people are interested in hearing about them.”

Lucas shared examples of artisanal and small-scale mining, which some experts believe are responsible for 70 percent of colored stone production. Even within this category, situations are diverse.

He said operations in Africa “vary tremendously.” Some of the artisanal mines have “illegal mining, environmental destruction, and conflict with larger organized mining.”

“In Sri Lanka, it’s structured and legalized – there are partnerships with the mine owners, the people who put up the capital, the land owners, and the miners.” In Mozambique’s ruby mines, however, unlicensed miners called garimpeiros often mine on Gemfields’ property, which can be a problem since they don’t “have an investment in restoring the environment” as Gemfields does.

In Pailin, Cambodia, there is “more of a problematic situation,” with concerns such as bribery, disease and an overall lack of legal, formalized structure to the mining system.

“Artisanal mining is not one type of a situation around the world – it’s not always positive, it’s not always negative,” Lucas said. “One way forward is for the industry to provide opportunities for all artisanal miners to come into the formal system and be protected. This could help protect the environment and the rights of larger mining companies and their investors, as well as create a transparent supply chain.”

Lucas noted that one technological development is changing artisanal mining: the smart phone. “You have someone in the middle of nowhere, they take a picture and they email it to Bangkok for a quote,” he said. “The smart phone is revolutionizing the independent miner with connections all over the world.”

Another factor in the supply chain is that countries like Sri Lanka to Colombia cut gemstones at their source. In Colombia, for example, almost all emeralds are cut in-country. “They have become the experts in cutting Colombian emeralds,” he said.

Lucas said this is part of an overall trend. “The divisions that used to exist in jewelry mining, cutting and manufacturing are blurry. A lot more vertical integration and consolidation is going on,” he said.

The CEO of RMC Gems, for example, told Lucas that five or 10 years ago, he had a large number of small companies – other wholesalers, jewelry manufacturers and retailers − as clients. Most of those companies are gone or have consolidated, so now the companies he works most with are jewelry television programs, large jewelry manufacturers and retail chains.

“The small people are less and less able to compete and add value,” Lucas said. “The larger, vertically integrated, better-funded companies are taking over in the business.”

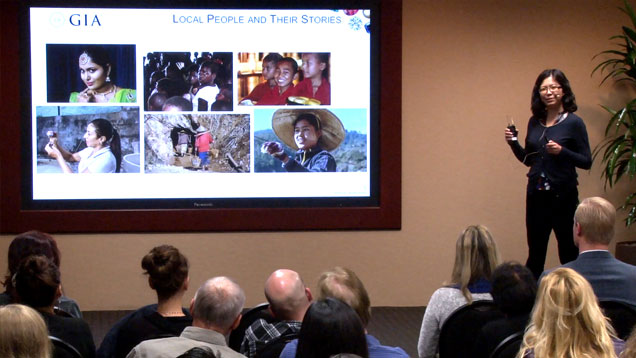

Dr. Tao Hsu explained that upon beginning her field research with GIA, she was struck by the stories of the diverse individuals and families around the world who make up the colored stone industry. Video image capture by Albert Salvato and Larry Lavitt

Dr. Tao Hsu explained that upon beginning her field research with GIA, she was struck by the stories of the diverse individuals and families around the world who make up the colored stone industry. Video image capture by Albert Salvato and Larry Lavitt

Hsu said you have to talk about China when you are talking about manufacturing, because “they manufacture everything for the rest of the world – including colored stones.”

She said one of the most striking aspects of a trip they took to China’s Guangdong province was that, regardless of the size of the facility, “everywhere you visited, you saw the focus and efficiency of the cutters.” In that particular area, where huge manufacturing facilities are clustered, companies are even promoting “China Cut” as a brand.

Lucas visited Jaipur, where he found “all types of sophistication levels,” calling it “an amazing place to see modernization and tradition side-by-side, hand-in-hand.”

He also learned more about a retail player that’s changing the landscape for colored stone manufacturers: jewelry television.

“The biggest growing market is jewelry television,” Lucas said, noting a colored stone manufacturer they interviewed there who loves that jewelry television goes from the high- to low-end and that they buy in “huge” volume.

One vertically integrated jewelry television entrepreneur told the GIA team his company’s team of 3,000 produces one million pieces of jewelry a month − by creating engaging programs that show the customer where the stones come from and how they are made into jewelry: the romance and adventure story.

“Their customer wants to be entertained. They come home and turn on the television – they’ll go to the mines, they’ll see the cutting,” Lucas said. They become engaged with the story of the stone and call in and make a purchase.

“I think you’re going to see an expansion of this,” Lucas said.

Hsu said the Chinese market, which the duo visited and wrote about in 2014, “is now the second largest market for jewelry and luxury goods.” The Chinese, she said, bought about half of the luxury goods in the world, particularly when shopping overseas as tourists.

The customers, companies and channels may evolve, but Lucas stressed that the story was still key.

He told of mine operator Marcelo Ribeiro, who had a unique emerald graded at GIA's New York lab and unsuccessfully tried to sell it to a New York wholesaler. Disappointed, Ribeiro took the stone to a show in Hong Kong. A high-end retail jeweler from Bangkok liked the color of the stone, but wanted to know more about it.

“Marcelo told him about the Belmont mine, the environmental protection, the sophistication in the operation, the family history, about the workers at the mine, their cutting at the mine,” Lucas said. “This guy was sold, he had a customer for it … and the mine-to-market story is what sold that stone.”

Jaime Kautsky, a contributing writer, is a GIA Diamonds Graduate and GIA Accredited Jewelry Professional and was an associate editor of The Loupe magazine.