Gemfields Bets on Gemstone Market’s Growth

January 26, 2015

Indeed, when Gemfields’ CEO Ian Harebottle speaks about the colored gemstone industry, the word “potential” comes up in just about every sentence. He believes that colored gemstones’ share of luxury goods sales could increase greatly around the world—potentially rivaling diamonds—if jewelry manufacturers and retailers could count on regular supplies, stable pricing, consistent grading, and increased marketing support. He has set his company’s goals on doing just that.

Gemfields, he believes, can be the change agent to lift gemstones to their rightful place in the market.

The company claims to be the world’s single largest known mining source of emeralds, with the production from its Kagem mine in Zambia, and is heading toward being able to make a similar claim for rubies, with its Montepuez mine in Mozambique. The company also operates the Kariba amethyst mine in southern Zambia.

The smaller emeralds have a combined weight of 125 ct. Photo by Robert Weldon/GIA,

courtesy Gemfields.

In a break from most emerald and ruby producers, Gemfields sells its production openly through auctions, instead of through a private dealer network. This, according to Harebottle, both ensures that the company receives market-based, competitive prices for its rough, and gives a much wider range of leading global dealers access to supplies.

The company’s ambitious strategy consists of simultaneously tackling the following challenges: consistency in its product line, pricing, and grading. And it does this from the moment they mine the gemstones. “Consistent supply,” says Harebottle, “is where everything must start.”

Consistency has always been one of the most problematic challenges to the industry. Usually, when a deposit is discovered, small-scale miners flock to an area while the pickings are relatively easy to find, only to abandon it after the deposit dwindles, if quality of the gem material declines, or when the cost of inefficient extraction is more than the return—especially if a new, more lucrative area is discovered. The Winza ruby and sapphire deposit in Tanzania, which was discovered in 2007, offers an excellent example. For two years, gems flowed plentifully from the mine, but now, scarcely six years later, the primary deposits have been largely worked out, and very little fine material is easily accessible and reaching the market.

Additionally, many small mining operations avoid paying taxes and duties and then abandon the area after the easy shallow pickings have been removed, leaving the deeper-lying goods in the ground.

Gemfields’ high cost structure, supporting more than 1100 employees in three countries, and the capital costs of securing and operating a mine, limits the company’s ability to withhold goods when the market is rising, like many major gem dealers do, but they are still able to retain at least one year’s worth of emerald and ruby inventory at any given time for continuity of supply. Gemfields prefers to manage obtainable prices by driving demand, rather than trying to do so by holding back supply. This age-old speculative practice invariably creates shortages that drive prices even higher, but stymie efforts by downstream retailers and dealers to create consistent jewelry lines.

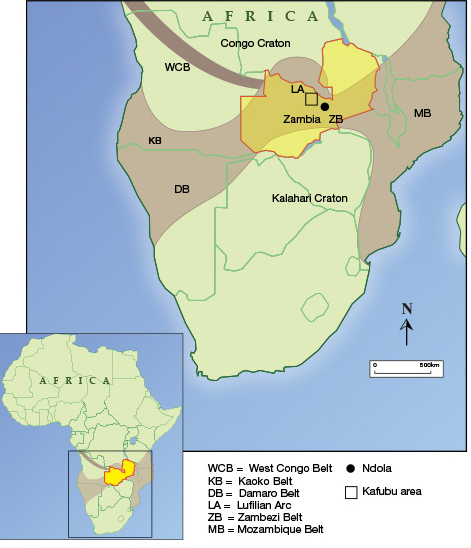

intersection of the continent’s Pan-African belts. Map reproduced from John et al., 2004.

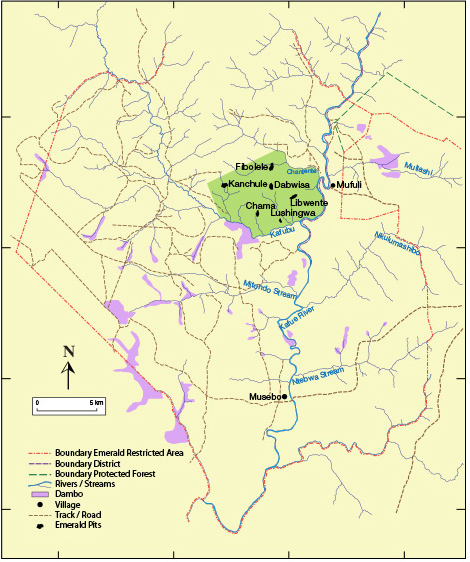

Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

From this rough, Gemfields established a detailed grading system to make its goods more appealing and understandable to the market. “It is the key to providing consistent supplies. Clients can know what they are buying, and count on goods being consistent at every sale. Confidence allows them to buy only what they need, in relatively large volumes, thereby allowing them to build out collections, improve their own economies of scale (in much the same way as many diamond sightholders are able to do) and further assist them in supporting these production runs with the associated marketing campaigns,” Harebottle says.

In the kilometer-long mining pit, workers perform a “quick sort,” washing the ore and then gathering the emerald crystals that have been blasted loose before the ore is sent to the washing plant. These are then placed through slots in padlocked and numbered boxes located nearby. The remaining ore is trucked out and sent to the crusher for further recovery.

However, security demands that even the matrix must be accounted for, Ameriya explained, adding that the cleaned crystal is weighed along with the pieces of waste matrix to determine if the numbers tally with the pre-cleaned weight.

The production is broken down into four basic grades: “premium emerald,” “emerald,” “beryl 1,” and “beryl 2.” After that, the premium emerald and emerald are run through sizing sieves to sort by weight. Next, they are divided by color: green with a secondary hue of yellow and green with a secondary hue of blue.

crystal before adding it to an assortment. Photo by Robert Weldon/GIA, courtesy Gemfields.

In its first year of operating Kagem (fiscal 2007), Gemfields reported that it mined 9.4 million carats of emerald and beryl. Production increased slightly the following year, but leapt to 28 million carats for fiscal 2009, after Kagem upgraded its processing capacity. In 2010, production fell back to 17.4 million carats then fluctuated greatly: 35 million in 2011, 21 million in 2012, and 30 million in 2013. The company reported it mined 20.2 million carats of emerald and beryl for fiscal 2014, down nearly 10 million carats from the previous year. With 8% representing the finer material, such production would work out to about 1.6 million carats in fiscal 2014.

Revenues too, have been volatile. In 2011, the company reported sales of $40.9 million, jumping to $83.7 million the following year. However, in 2013 Gemfields reported a revenues of just $48.4 million, and a loss of $22.8 million. Included in the debit side, however, were costs associated with its acquisition of the Fabergé brand ($90 million in stock transfers). Also, the relocation of its primary emerald auction from Singapore to Lusaka delayed at least one sale until after the fiscal year had closed. In 2014, revenues soared 230.8% to $160 million as Montepuez ruby production came online, and the rescheduled fiscal 2013 emerald auctions swelled the total. The company, once again, turned a profit of over $8 million.

MONTEPUEZ

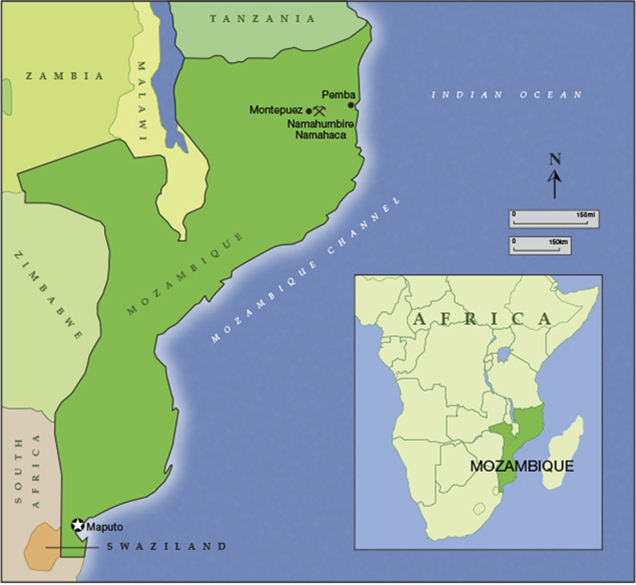

Though rubies from Mozambique dominate today’s gemological discussions, their discovery is relatively recent. Indeed, they are not mentioned in 20th-century gemological literature, or in pre-1990 geologic studies scrutinizing this East African country’s gem potential.Fine rubies are rarely plentiful anywhere, but they have been found in abundance in the Mozambique Belt, a geologic orogeny that stretches northward from Mozambique through Tanzania, Kenya, and Ethiopia. The Mozambique Belt yields many of East Africa’s gem materials, including tanzanite, tsavorite, a host of yellow, red, and color-change garnets, chrysoberyls, and, of course, rubies and sapphires that were discovered in Kenya and Tanzania in the mid-1900s.

Perhaps the greatest irony is that Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony now dusting itself off from decades of Communism and civil war following independence, will likely emerge as one of the most lucrative ruby sources in this century.

- Premium ruby: The highest qualities over 5 grams

- Ruby: The highest qualities below 5 grams and lower colors of about that weight

- Low ruby: These are segregated into three grades of color, size, and clarity. Much of this production has small fissures treated on-site with borax.

- Corundum

- Sapphire

- Small goods: -4.6 mm

The graders at Montepuez are helped by the fact that the source of most of the ruby and premium ruby is Mugloto, which produces material that is astonishingly homogenous in size and color, according to Gemfields. Unlike the numerous emerald grades at Kagem, the top ruby from Mugloto falls into only four basic grades—A to D—depending on color and saturation. The A and B grades have colors resembling Burmese Mogok material, while C and D colors resemble the slightly darker Thai material.

Mugloto produces 2 to 3 carats per metric ton of ore. The material in the primary deposit, Maninge Nice, varies from “sapphire” (highly included, tabular, and fissured pinkish material) to the fine, cuttable qualities. At 162 carats per ton, there’s a lot of it. In fact, the deposit is so rich that visitors to the area literally walk over ground speckled with corundum—of all qualities.

Unfavorable news reports about such “glass-filled rubies” sold as natural without disclosure have cropped up in the US and other countries during the past several years, leading many gemstone dealers to say that such goods undermine confidence in all rubies. However, Harebottle sees no threat from unfavorable publicity spilling over to Gemfields’ finer production.

“First, I have no issue with treatments so long as they are clearly disclosed! Next, I believe consumers will work out what’s best for them, especially when supported by grading reports from recognized and respected laboratories.”

So, for him it’s about [informed consumer] choices. Top-quality ruby is an expensive stone, whereas treated goods are much more affordable and ubiquitous. “Should there not be scope enough in the market for various qualities and treatments of ruby, without one affecting the other and with each perfectly suiting an individual consumers finances and purchasing needs?” Harebottle asks.

Indeed, the ore processing and washing equipment remains basic and relatively small, and the miners have been unearthing far more than this equipment can process. The company plans to at least double the capacity of the washing operation by the spring of 2015.

SALES

Gemfields’ open auctions are a radical departure from traditional colored stone industry practice and indeed much closer to that which has been applied within the diamond industry for the past many years.For as long as there has been a gemstone industry, most colored stone producers have sold privately through an established network of dealers, now mainly in South America and India for emerald and other gem materials, or in Thailand for corundum. As a result, prices have often been erratic, with huge variations on similar material.

But Gemfields believes auctions, supported by detailed grading, allow for more transparency and truer price discovery. Harebottle says this price discovery has resulted in a marked reduction in the overall volatility of the per carat/quality prices achieved at its annual emerald auctions which the company has run since 2011. “In the old days the variance between the lowest bids and the highest bids could have been as high as 10,000%.

We had a situation where many of the world’s experts were basically bidding on the same rough, and yet the prices they were offering could be quite varied at times. Now, though we still have some ‘cheeky’ customers [making low bids] on the odd occasion, the variance is far less and the prices offered are far more stable¾between 100 and 200% at most.” Harebottle attributes this to a natural settling-in of the buyers, but also because its customers are now able to better understand the run of production. According to Harebottle the process is as follows:

- All of Gemfields’ auctions operate on a straightforward closed bid/tender with reserve system.

- Before each auction, Gemfields works out its Minimum Reserve Prices (the lowest amount we are willing to accept for any given schedule), and this is placed in the sealed bid box before the auction starts.

- The auction attendees then have a number of days to evaluate the goods, after which they must place binding offers on each schedule. Gemfields doesn’t accept a single bid for the entire auction—all of the lots as a whole.

- These offers are written into bid-books, which are placed into the bid-box by the attendees. They can place more than one bid per schedule, but only the highest bid is considered.

- After the close of the auction, all of the bids are evaluated for each schedule, where the bids received are higher than the pre-set minimum reserve price (MRP). Each schedule goes to the highest bidder.

- After all of the bids have been evaluated, the attendees are notified which company won which schedule (just the company name and which schedule they won, not what they bid). Any schedule where the bids did not reach the reserve are also identified, but in this instance Gemfields does disclose what its expected MRP was so that the customers are at least able to have some idea as to the Company’s expectations going forward.

At first, the company had reservations about holding the auctions in Zambia—expressing fears that the key buyers may have been reluctant to attend. However, buyers have attended, and the most recent sale in November 2014, achieved a record per-carat price (nearly $66) for 530,000 carats, divided into 17 lots. More than 88% of the goods offered were sold. Harebottle says that this helps prove the international scope of the business.

Traded goods, or emeralds that are not mined by Gemfields themselves, are sold in Jaipur, India, where many of Gemfields’ clients do business, and where an established emerald cutting business has existed since Moghul times. Montepuez material is sold in Singapore.

Gemfields hopes to reduce the volatility of prices caused by the “here today, gone tomorrow” mentality that has pervaded the gem business. For gem dealers, this means the ability to replace their original stock with similar goods once it is sold. For jewelers and designers, such a model offers the ability to create repeatable jewelry lines from emerald and ruby, and most importantly it justifies the concerted marketing efforts required to bring colored gemstones back to the forefront of the discerning consumer’s minds.

Gemfields, in addition to its own production, buys material from local markets. Last year it acquired some $8.5 million worth of emeralds from open market sources, which it sold separately from its own production.

For Harebottle, segregation of this material is important, and a matter of accountability. “Even though we apply the well-recognized Know Your Customer protocols, we can’t know for sure what’s happened to these (outside) goods; how they were mined, or the extent to which the environments in which they were mined may have been treated, but we are able to guarantee that all taxes and royalties and are covered from the time they have reached our hands,” he says. In some cases, Gemfields believes it is buying back material poached from its own concession, or even filched at its sorting operations, despite intense security throughout its mine in Zambia, which is surrounded by a high chain link fence, security cameras, and guards at key spots throughout the mine checkpoints, and along the access roads.

Harebottle says he’s seen a lot of sad cases—garimpeiros who become ill or dehydrated working, as they do, without protection from the sun.

“We can understand their circumstances, but can’t condone the theft or destruction of the environment,” he says, noting that Gemfields and the government, by reserving certain areas for miners, try to achieve a balance that is fair to all.

Complicating matters, however, is that many garimpeiros are migrants from other areas, or other countries. “They carry these gemstones out of Mozambique illegally, paying no taxes or royalties, so neither the communities nor the country benefits,” he explains.

MARKETING

Gemfields’ sales model was derived, with modifications, from De Beers’ single channel marketing formula—a formula Harebottle used at his previous affiliation with the tanzanite mine, TanzaniteOne.Like De Beers, he and then CEO, Michael Nunn, wanted to manage supply and had the advantage of owning the largest concession in the world’s only tanzanite deposit. In tandem, they devised a sales strategy where they chose and vetted customers—or sightholders—who purchased their goods at regularly scheduled sales. In addition, they devised a rough tanzanite-grading grid to help sightholders fully understand the qualities they were buying. Finally, much like De Beers did throughout much of the last century, TanzaniteOne established a marketing arm, the Tanzanite Foundation, to help increase demand and gradually lift prices.

“Further, we wanted some sort of pricing guide for tanzanite, and we wanted certification [or identification reports] for the gem to help provide increased transparency for the trade and consumers alike,” Harebottle says.

Harebottle notes that much was learned from those experiences, including the fact that it is not necessary to control a large portion of the supply. “We thought that a De Beers style market share was the key. But we have changed our view.

“The key driver of value today is the position a product holds in the mind of the consumer,” he stresses. ”Much of this is achieved through advertising. Along with positioning our product at the forefront the consumers mind, there has to be a clear understanding of what Gemfields stands for: ethics, transparency, legacy, provenance, excellence and creativity.”

emerald from Kagem. Photo courtesy Alexandra Mor.

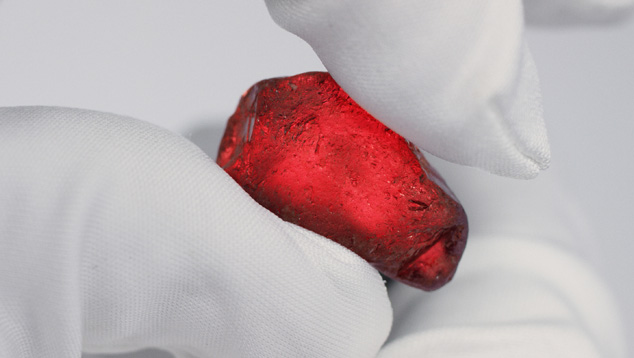

Referring to the 40.23 ct ruby, Harebottle says that Gemfields is committed to following the stone from the mine to its ultimate owner, after pre-forming, polishing and setting. (See Box A).

| Box A: Paydirt and Corporate Responsibility |

|

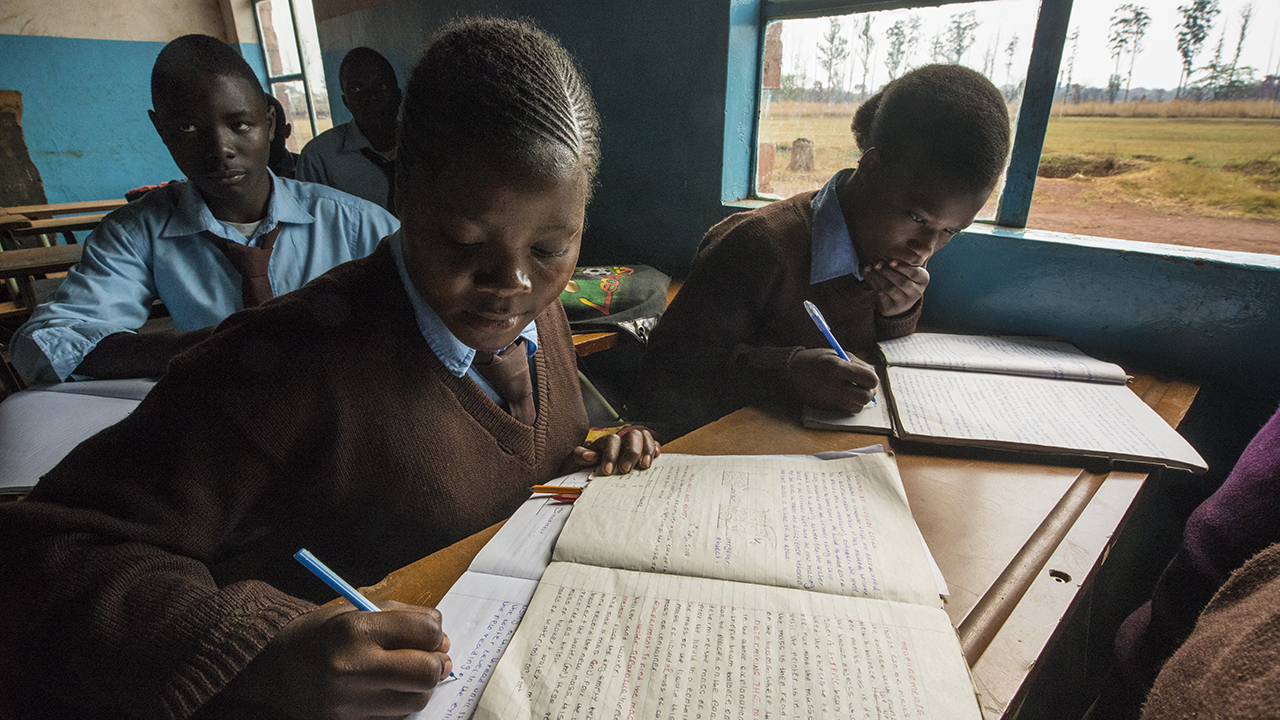

Joseph Chilambwe, Senior Manager in charge of community relations for the Kagem mine in northern Zambia, extends his arm in a sweeping arc at the acacia tree forest before us. “Kagem has taken on the responsibility for this entire area, from our mine to the highway.” The Kagem mine is the largest emerald mine in Zambia, operated by Gemfields in partnership with the national government. The area, extending about 12 miles to the main highway running to the copper mining town of Ndola—about a three-hour drive—had been sparsely populated before emeralds were discovered there. Today, there are small plots where families have settled – families of illegal miners, farmers, or simply people looking for an income—scattered throughout the forested rolling hills around the mine area.

Building a Sustainable Community

With Chilambwe at the wheel, we proceed down a reddish-brown dirt road that slices through the brush, on the way to a village called Kapila where Kagem has constructed a three classroom school. “This is the main road, which we maintain. But because the people are so scattered, we had to build eleven kilometers of additional roads so they can get to the classrooms,” he says.Turning into an abbreviated side road, he stops the car near several traditional houses that sit beside lush fields contrasting vividly against the surrounding dry scrub. “These families are part of the Kapila Green Farmers’ Cooperative that supplies our mine with fresh vegetables.” The fields are demarcated by well-tended irrigation ditches and yield cabbage, potatoes, onions, and several other staples. “In fact, the program is so successful that they’ve grown crops far in excess of the mine’s needs so we now have to find a way of getting them to market.” The school lies several miles past the farm, in an open field beside a formation of anthills that protrude from the landscape like monuments. The Kapila school, accommodating grades one to seven, for which Kagem provides all support, has three classrooms with teachers and aides also paid for by Kagem. Each classroom has three rows of wooden tables and benches that accommodate two or three students across, depending on the age group. The instruction consists of basic literacy (including English), mathematics, and home economics, though the instructors note proudly that at least one of their students has gone on to study at a university. Technology and computer training are limited by the lack of electricity in the region and the difficulties that some of the students have traversing the distance to the classrooms each day. “This school is not yet recognized by the government,” says Chilambwe, “so we still support it fully until then.” In Chapula, another five kilometers down the road, Kagem built a larger school with seven classroom blocks that serves children up to 10th grade, notes Chilambwe. Nearby is the Nkana clinic, designed to service basic medical needs for both Kapila and Chapula. We arrived too late to talk with the staff but Chilambwe told us it employs a nurse to handle routine care and has access to an ambulance for more serious cases. Montepuez in Northern Mozambique is also located in a relatively remote area, the closest major city being the port of Pemba, approximately a three-hour drive to the southwest. Our time at Montepuez was too limited to visit the surrounding areas but the mine’s project manager, Sanjay Kumar, explained that the company has developed drinking water wells for two local villages, Namanhumbir and Nacoja, both about ten miles from the mine site. It has also renovated the school and village market at Namanhumbir and contributed to renovating schools in several other villages. “There are a lot of other things that we do for the people in the area,” Krumar says. “There are thousands of illegal miners in our concession and sometimes we have to find medical care for those who have fallen from dehydration.” Gemfields had some major fence-mending to accomplish with the local community after it assumed control of the concession in 2012. Before then, there were numerous instances where guards at the mine shot at, and occasionally killed, illegal miners (garimpeiros). This long had been a problem in the area, according to local press reports. In one instance, shortly before Gemfields’ arrival, guards fired on 300 miners, killing one and wounding two others. Additionally, Gemfields announced at its December 2014 auction of Montepuez rubies that it has begun supporting anti-rhino poaching efforts by helping to fund the aerial surveillance of game preserves along the 300 mile-long border between Mozambique and South Africa. The African rhinos are highly endangered and Gemfields named a 40.23 ct. ruby it discovered in November 2014, the Rhino Ruby, to raise more awareness of the issue. |

Gemfields acquired some glamor of its own in 2013, when it bought the venerable Fabergé jewelry brand, which had been revived six years earlier. Harebottle says that the brand will provide the perfect platform for its gemstones and Gemfields desire to reinvigorate the jewelry sector as a whole. The brand operates about a dozen boutiques around the world and Fabergé designers have integrated Kagem emeralds and Montepuez rubies into its jewelry creations.

Can Gemfields accomplish all it has set out to do?

Doug Hucker, executive director of the American Gem Trade Association, likes the company’s emphasis on marketing and responsible mining practices. He also believes that steady supplies can be a great benefit, but doubts that Gemfields could bring order to a traditionally disordered trade.

“They want to establish consistent pricing. Perhaps they can for their product: Zambian emeralds. But Colombian emeralds are different goods,” he explains. “So it’s not likely that Gemfields’ prices will completely translate.”

Additionally, he says that “getting these (gem producers) to come together is like herding cats. Second, it takes immense resources and high market share to influence supplies and prices across-the-board. It is not certain Gemfields has the market share to do this.”

Harebottle realizes that the gemstone industry remains skeptical about Gemfields’ market initiatives, especially pricing. Many are particularly worried that detailed, consistent grading leads to commoditization. He doesn’t dispute that. Indeed, he believes that a Rapaport type price list would potentially be a boon to the industry in time as it supports increased consumer confidence, especially for stones over two carats, but he also understand many of the inherent challenges.

“Some short-term profits may be lost, but the industry will more than make up for that through increased sales because people will know the value of what they have purchased instead of dealing with (the current state of) huge variations in price and uncertainty.”

He admits that this is not a popular view among most colored stone dealers and producers who he believes are still stuck in the past, but that colored stone demand has come a long way in recent years, though from a low base. “Increasing transparency and increasing consistency of prices and supplies will result in more demand for colored gems across the board. I have no doubt about that and that it will be good for everyone when it happens.”

Russell Shor is Senior Industry Analyst, and Robert Weldon is Manager of Photography & Visual Communications.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors would like to acknowledge the kind assistance of Ian Harebottle, CEO of Gemfields. Numerous members of the Gemfields team, namely Vijay Ameriya, Joseph Chilambwe, Robert Gessner, Anna Haber, Ashim Roy, and Philippe Ressigeac were extremely helpful in showing the authors anything they asked to see.