A Visit to the Kagem Open-pit Emerald Mine in Zambia

December 31, 2014

Introduction

Today, strong and ever-expanding demand for colored gemstones has made the sourcing of these fine gems one of the industry’s biggest challenges. The Gemfields operation at Kagem is a model for possible future colored gemstone mining operations as well as for participation in the mine-to-market supply chain. The operation encompasses processing, sorting, and grading, all intricately tied to Gemfields’ marketing campaigns and auction systems. Gemfields offers expertise in capital investment, mining, marketing, best business practices, government and local partnerships, and sustainability—a complete strategy that carries all the way to its auctions.The GIA team was led by Vincent Pardieu, GIA Senior Manager of Field Gemology, based in Bangkok. Accompanying him were Andrew Lucas, Manager of Field Gemology in Carlsbad; Tao Hsu, Technical Editor of Gems & Gemology in Carlsbad; videographer Didier Gruel; and expedition guest Stanislas Detroyat. This was a return visit for both Vincent and Didier—the third for Vincent since 2011 and the second for Didier, who first visited along with Vincent in 2012. For the others, it was their first opportunity to observe the mine and its operation, which they had been following from afar for a number of years.

The GIA Team

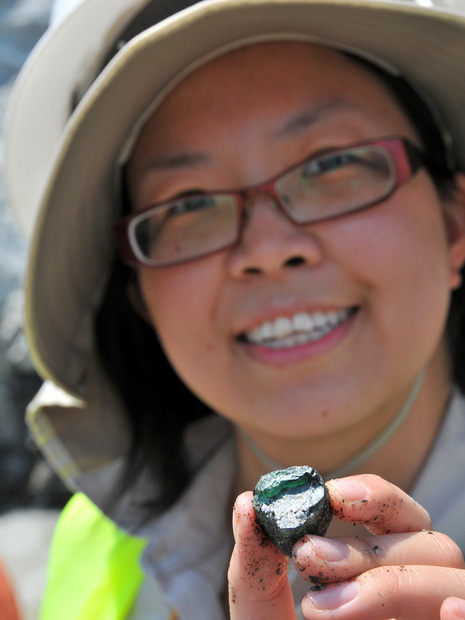

The team’s main objectives were to collect new on-site reference samples for the GIA Lab as well as to witness, document, and report on the evolution of the mining activity. The team was able to retrieve many pieces of emerald rough directly from the host rock to use for new reference samples, and to study the production at the sorting house. They spent several days observing operations at the mine and interviewing Gemfields’ management and staff, gaining a deep understanding of the mining operation and how it fits into Gemfields’ goals of revolutionizing the colored stone industry.

Tao Hsu collected one of the most impressive additions to the GIA emerald reference

database from Kagem’s Chama pit. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

database from Kagem’s Chama pit. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

The Country of Zambia

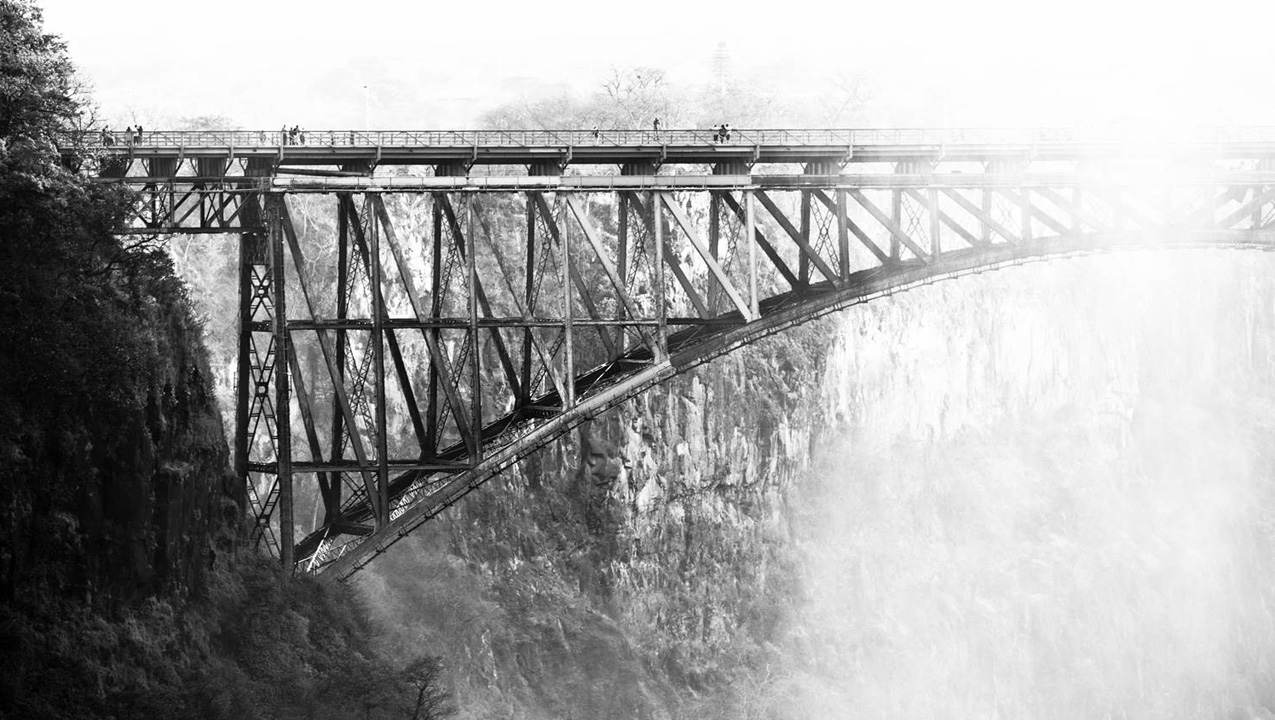

Zambia is a landlocked country in southern Africa, surrounded by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, and Angola. Its total area is 752,618 square kilometers. The climate is mostly tropical, with a rainy season from October to April that brings substantial amounts of rainfall. The terrain is mostly high plateau with some hills and mountains. While the country is landlocked, the Zambezi River forms a natural border with Zimbabwe and allows for transportation of materials by boat. The river has also given rise to a major tourist industry at Victoria Falls for both Zambia and Zimbabwe. Lake Kariba, the world’s largest reservoir by volume, also borders Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Victoria Falls and the Zambezi River

Zambia’s population consists of an estimated 14.5 million people, encompassing several different ethnic groups. The largest groups are the Bemba and Tonga. English is the official language because it’s a former British colony, but over 70 languages, mostly dialects, are spoken in the country. Most are related to the Bantu family of languages.

Zambezi River Wildlife

Growth of the Zambian economy was strong between 2005 and 2013, averaging over six percent a year. Traditionally, since its discovery in 1895, copper has been the country’s main source of revenue. The privatization of government-controlled copper mines in the 1990s and the surge in copper demand and prices over the last decade have made Zambia’s copper industry profitable. Over 43 percent of Zambia’s copper exports go to China, a major buyer. The presence of a strong mining culture around Kitwe, the capital of the Copperbelt Province where the Kafubu emerald mining area is located, had a direct impact on the establishment and success of emerald mining in Zambia. Zambia is known to produce several other types of gemstones, including amethyst, beryl, and garnets, but emeralds are Zambia’s most economically important gemstone export.

Local employees are hired to work at Kagem’s washing plant. Photo by Stanislas Detroyat.

History of Zambian Emerald Discoveries

Gem-quality emeralds are found in north-central Zambia, near the Kafubu River and about 45 km southwest of Kitwe, a town considered the hub of the famous Zambian Copperbelt Province. It is also home for numerous workers involved in the nearby emerald mine. Early European copper prospectors like William Collier had to wait until the 1920s, when a technical breakthrough made it profitable to mine their discoveries.The first discovery of beryl in the Kafubu area was made in 1928 by Dick and Baker, geologists from the Rhodesian Congo Border Concession Company. They completed their investigation in 1931, concluding that the deposit had little economic significance. This decision was probably due to the company’s main interest in copper at the time.

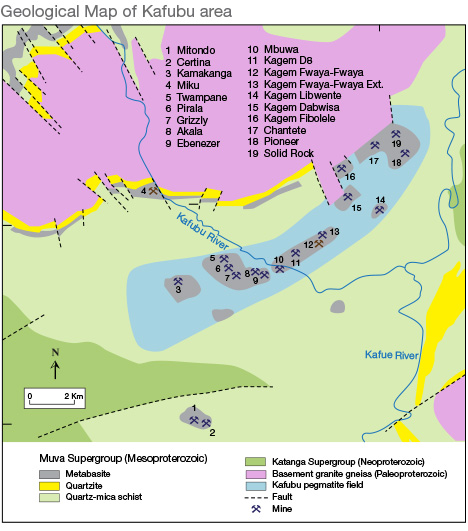

The Kafubu area is well known as one of the largest emerald-producing areas in the world.

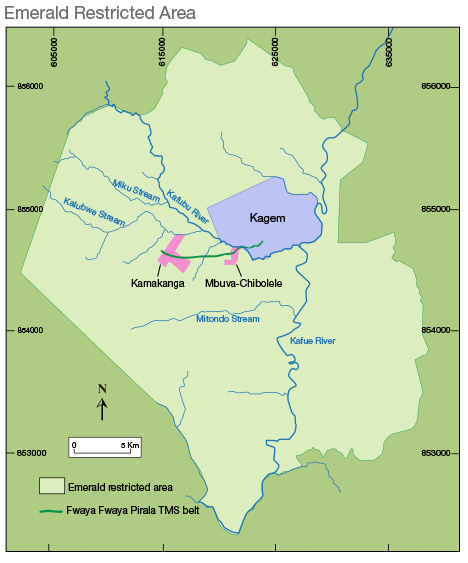

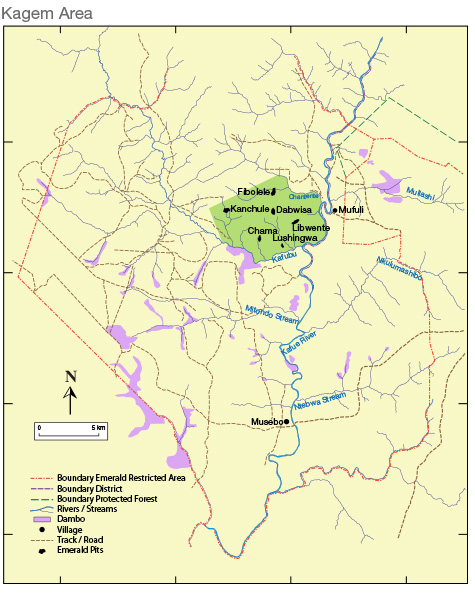

Although the initial prospects for beryl production were not overly encouraging, further exploration was undertaken by the Rhokana Company in the 1940s and by Rio Tinto Mineral Search of Africa in the 1950s. In 1966, the claim was passed on to a small private company, Miku Enterprises Ltd. The rights passed again to a government-owned company, Mindeco Ltd., in 1971. Zambia’s Geological Survey Department then mapped the Miku area and located the deposit. They published the results in 1972 and 1973.These works, plus discoveries made by some local miners of deposits called Kamakanga, Pirala, Fibolele, and Fwaya-fwaya, led to the rapid expansion of emerald exploration and production in the 1970s. Huge economic potential and extensive illegal mining soon forced the government to relocate the local population and form a “restricted zone” called the Ndola Rural Emerald Restricted Area (NRERA).

Ndola Rural Emerald Restricted Area (NRERA) is located within the Kafubu area.

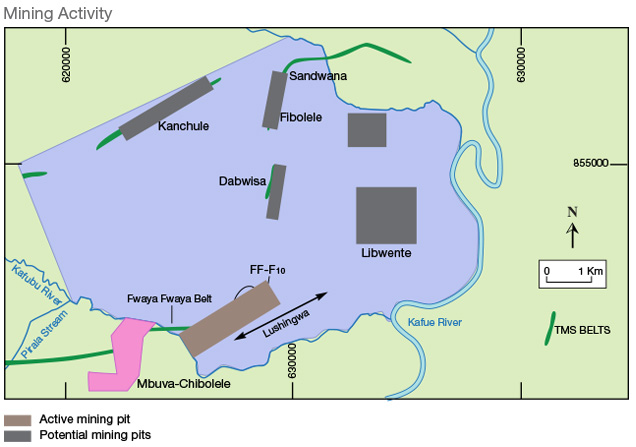

Kagem mine is on the north side of the Kafubu River. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

The establishment of this restricted area allowed only government-authorized mining by large-scale companies and small-scale local miners. In 1980, government-controlled Reserved Minerals Corp. took over all rights and delineated a mineralization area of about 170 square kilometers. The production from this area has since increased significantly. In the same year, Kagem Mining Ltd., 55 percent of which was owned by the Zambian government, was authorized to explore and mine in the Kafubu area. Since 1984, the mine has consistently produced some of the finest Zambian emeralds. Kagem properties are located on the north side of the Kafubu River. Hundreds of prospecting claims are also being worked outside of Kagem’s concession.Kagem mine is on the north side of the Kafubu River. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

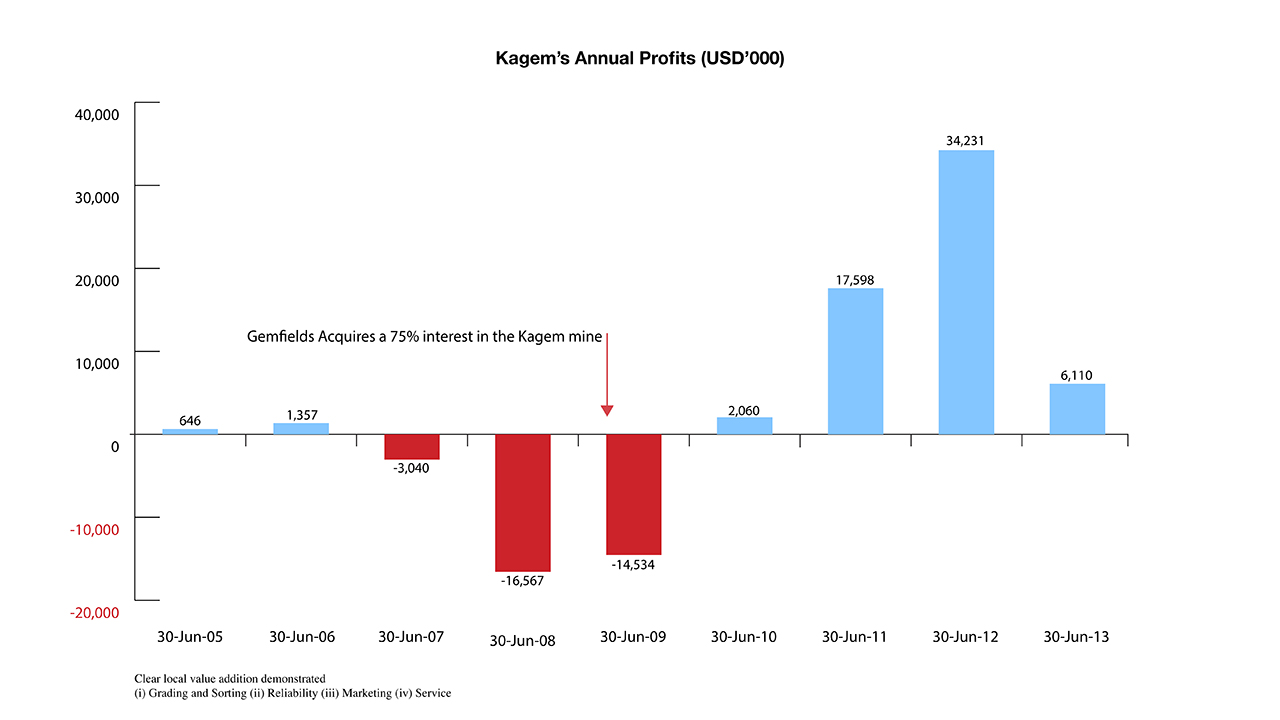

In 2004, the British public-listed Gemfields Resources PLC started systematic exploration near the Pirala mine, south of the Ndola River, and made some important discoveries. Mining began in 2005. By 2007, Gemfields had already acquired 100 percent ownership of two mines in the area. In June 2008, Gemfields formed a collaboration with the Zambian government, establishing a 75/25 ownership split of the Kagem emerald mine.

In 2008, before Gemfields took control, the floor of the big pit at Kagem had almost no minable ore. By the following year, its yield had increased greatly. Photo courtesy Gemfields.

When Gemfields acquired control of the mine in 2008, the main open pit was yielding almost no minable ore. The company invested huge amounts of capital and used its know-how to change the conditions there. By the time the fiscal year ended on June 30, 2009, Kagem had produced 27.6 million carats of emerald at an operating cost of about 40 cents per carat (data from Gemfields PLC operational updates, August, 2009). From 2009 to the present, Gemfields has held nine high-quality and six low-quality emerald rough auctions.The company also collaborates with Collector’s Edge Minerals, Inc., a Colorado company, to develop emerald specimens for marketing to mineral collectors. The first emerald specimens produced by Kagem debuted at the 2009 Denver Gem and Mineral Show. Kagem is now considered the world’s single largest emerald mine.

The Kagem mine yields fine emerald rough like this crystal in matrix. Photo by Stanislas Detroyat.

The key to Gemfields’ Kagem success story seems to be the company’s knowledge regarding mining primary deposits, raising capital, financial planning, and exploration. They have taken advantage of the already existing mechanized mining infrastructure in the Copperbelt Province, and also used their well-organized auction system to support their ability to obtain the best possible prices for their production.Regional and Local Geology

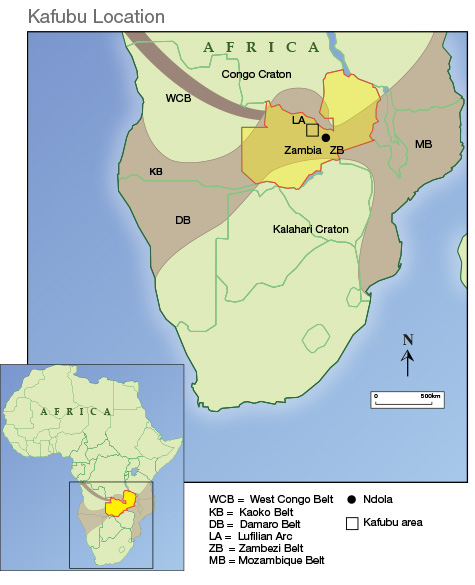

The Kafubu area is located geologically at the center of the transcontinental Pan-African belts in central-southern Africa. This is a critical area that separates the Congo craton to the north and the Kalahari to the south. In central Zambia, the Mesoproterozoic units are crosscut by the Pan-African Lufilian Arc and the Zambezi Belt. The crustal thickening and its intrusions are thought to be related to two corresponding orogenic events: the Mesoproterozoic (ca. 1300-1000 Ma [million years ago]) lrumde orogeny and the Late Proterozoic to Cambrian (ca. 750-500 Ma) Lufilian orogeny (John et al., 2004).

The Kafubu area is located in central Africa, at a critical intersection of the continent’s

Pan-African belts. Map reproduced from John et al., 2004.

Emeralds from Zambia can be of the same quality as their counterparts from other world-famous sources like Colombia, but they formed in quite different rock types. Unlike Colombian emeralds, emeralds from Zambia are rich in iron and have higher refractive index and specific gravity (Zwaan et.al., 2005). Emerald deposits in the Kafubu area occur within rocks of the Mesoproterozoic Muva Supergroup (1800-1100 Ma), composed of both metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks.Pan-African belts. Map reproduced from John et al., 2004.

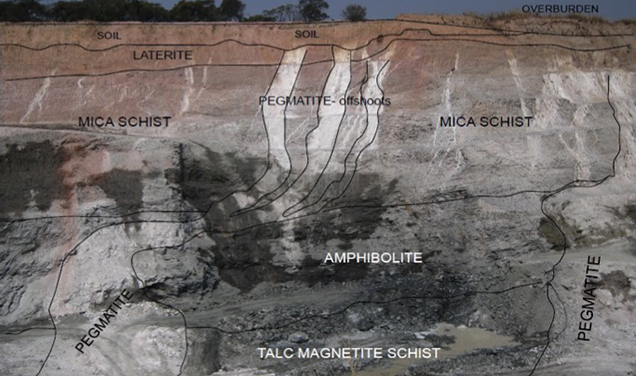

In the Kagem mine area, the Muva Supergroup overlays a basement complex that’s about 1,800 to 2,050 million years old. It consists of talc-magnetite schist, amphibolite, and quartz-mica schist, layered from the bottom to the top of the pit. These lithounits lie on top of mica schist and strike generally along ENE-WSW to NE-SW, with a low to moderate southerly dip. Pan-African pegmatites intrude into the entire unit. The pegmatites are believed to be related to neighboring granitic rocks that originated or were rejuvenated at the beginning of a global tectonic event.

All the Kagem emerald pits are located in the Mesoproterozoic Muva Supergroup. Besides

Kagem, there are many other emerald mining operations with similar geology in this area.

Map from Zwaan et al., 2005.

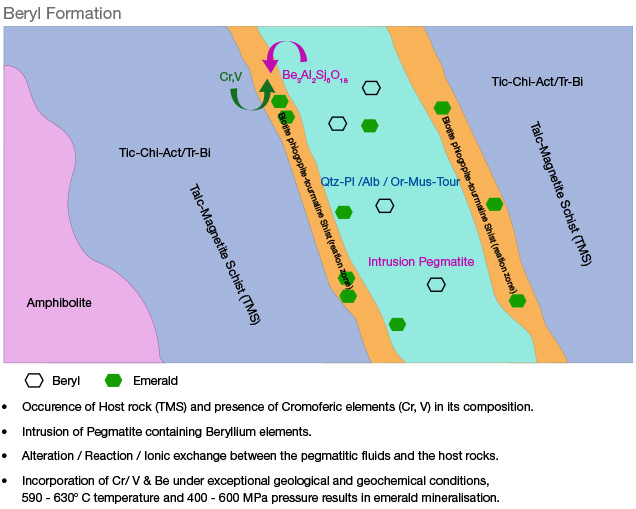

When the beryllium-rich magma and the fluid derived from it interacted with the surrounding chromium-and vanadium-rich host rock, ionic exchange occurred in the reaction zone between them. Within this reaction zone, the chemical components of chromium, vanadium, and beryllium mixed together under the right pressure and temperature conditions (400-600 MPa and ~590-630 °C) and chemical environment. These conditions led to the mineralization of both common beryl and emerald.Kagem, there are many other emerald mining operations with similar geology in this area.

Map from Zwaan et al., 2005.

The metasomatic reaction between the host rock and the pegmatite formed both common beryl and gem emeralds. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

There are two pegmatite phases in the mining pits inside the Kagem mine. Older, shallowly dipping (an average of about 16 degrees) quartz-tourmaline veins were crosscut by younger quartz-feldspar bodies. There are two schools of thought regarding the age relationship between the quartz-tourmaline veins and the pegmatites. Some believe that the emplacement of the quartz-tourmaline veins occurred toward the end phase of the pegmatite intrusion and others believe that they are older than the pegmatites. Both intrude into the talc-magnetite schist, whose parent rock, believed to be komatiite, formed during earlier orogenic events. Komatiite is a type of ultramafic volcanic rock that formed during the early history of the Earth (mainly between the Archean and Lower Proterozoic periods). It has extremely high magnesium content.Talc-magnetite schist provided emerald’s key element of chromium, while the pegmatites provided the beryllium. Based on previous research, it’s known that magnetite comprises up to about 4 percent of the total volume in the talc-magnetite schist and that the average chromium concentration in the magnetite is about 4-7 percent by weight.

Emeralds are found in both the reaction zones between the talc-magnetite schist and the pegmatites and in the quartz-tourmaline veins. The reaction zones are usually altered to phologopite-biotite-tourmaline aggregates, which are soft and easily disintegrated. The softness also provides an ideal environment for preservation of the emeralds. According to Kagem’s Senior Geologist, Robert Gessner, the best emeralds are usually found in the quartz-tourmaline veins. Kagem processes enormous amounts of ore annually, but only a tiny percentage produced from the emerald-bearing quartz veins is suitable as mineral specimens for collectors.

Robert Gessner, Kagem’s Senior Geologist, holds a piece of phologopite-biotite-tourmaline aggregate from the reaction zone. The rock is very soft and easy to break, and also provides ideal protection for the emerald crystal. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Typical layering from the bottom to the top of an open-pit operation starts with the oldest basement complex, consisting of gneisses, amphibolites, and kyanite-bearing schists (~2050-1800 Ma). It is followed by the talc-magnetite schist, with ages between 1800 and 1100 Ma; amphibolite; reddish brown quartz-mica schist; and topsoil about 3 to 5 meters thick. The talc-magnetite schist, amphibolite, and quartz-mica schist all belong to the Mesoproterozoic Muva Supergroup. Quartz-feldspar and quartz-tourmaline veins intrude into all of these units.

This is a general view of a cross-section of the big pit. The main rock units include pegmatite, mica schist, amphibolite, and talc-magnetite schist. Emerald is often found in the reaction zone between the pegmatite and the schist. Photo courtesy Gemfields.

In the Chama pit, the talc-magnetite bodies strike east to west while the pegmatites trend roughly north to south. The pegmatites trend toward the west due to some later deforming events. However, local variations are almost unavoidable. Shear zones, which are zones where deformation is notably higher than in the surrounding rock, and folds, are very common. Geologists guide the operation based on their onsite observations. There are some places where emeralds are more concentrated. When a quartz-tourmaline vein and a quartz-feldspar vein intersect each other in the talc-magnetite schist, this forms a “tri-junction.” The pressure and temperature conditions and an ample supply of the necessary chemical components create a nice environment for emeralds to form.

When a quartz-tourmaline vein and a quartz-feldspar vein intersect each other in the talc-magnetite schist, a “tri-junction” forms. The appearance of two pegmatite shoots makes this tri-junction ideal for the exchange of emerald-forming elements. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

There are many talc-magnetite schist belts in the NRERA. The most historically significant and productive of them is the Pirala Fwaya-Fwaya belt, which extends for 8.5 kilometers in an east-west direction. Two and a half kilometers of this belt lie within the Kagem license, which extends from the Kafubu River to Libwente. The largest operation, Kagem’s Chama pit, is located at the east-central part of the belt.Core drilling data proved a strike length of 2500 meters at Chama. The current open pit has dimensions of about 1000 meters by 600 meters and reaches a depth of up to 120 meters. Besides Kagem, there are at least five other mechanized mining operations and hundreds of active artisanal miners working in the area. The recent appearance of Chinese investors, previously involved in copper mining, is becoming more noticeable in multiple emerald mining operations.

The Mine

Zambia’s Kagem mine is located in the southern part of the Copperbelt Province, in the emerald mining area south of Kitwe. The first thing that catches your attention is its scale. Over a kilometer in length, it is enormous compared to most colored gemstone mining operations. The size of the pit is directly related to the geology, as the mining targets the phlogopite-biotite contact zone between the pegmatites and the talc-magnetite schist where the emeralds are found. The size of the pit is dictated by the need to access this contact zone.

The Kagem emerald mine lies in the Kafubu emerald mining area. Reproduced

courtesy Gemfields.

The mine had been operating under other management for 19 years when Gemfields came to Kagem six years ago. The operating Chama pit had a poorly excavated 60-meter highwall, covered with waste soil. The previous operation had targeted only outcropped contact zones, without removing waste or overburden. Miners were lowered into contact zones in excavator buckets.courtesy Gemfields.

Gemfields spent one year cleaning out the pit and removing the pegmatite and talc-magnetite schist to expose the emerald-bearing contact zones. Today, the highwall is 120 meters high, with professionally excavated benches of 10 meters each. Benches and berms provide a safe, stable highwall for mining operations. They removed a tremendous amount of rock, and the open pit is now 45 meters deeper, with a total depth of 105 meters.

Kagem increased the total depth of the Chama pit from 60 meters to 105 meters. The pit’s length is roughly 1 km. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Open-pit Mining Methodology

Kagem is primarily an open-pit mine. One advantage of open-pit mining is that it makes every carat of emerald accessible. An underground operation requires leaving walls, ceilings, and pillars intact for shafts and tunnels, limiting or eliminating access to the emeralds in those areas.Gemfields uses a strip-and-fill method to mine its deposits. A pushback occurs when they move the highwall of the pit farther back to continue exploiting the deposit. Since Gemfields took over, there have been four highwall pushbacks, with the fourth one now in progress. Ore production is currently taking place at the third pushback. The first three pushbacks were all 50 meters, and the fourth one is 75 meters. At the fourth pushback, three years of highwall waste stripping will provide enough ore for five years of mining. Based on resources estimated to be in excess of 1 billion carats, the mine is expected to have another 25 years of life.

An excavator strips the highwall of the pit and loads the material into the truck. The truck transports the material to its processing destination. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Gemfields uses a contractor to remove the mica schist/amphibolite waste during the highwall stripping process. The contractor removes about a half million tons a month, working 24 hours a day and seven days a week. Using its own operating fleet, Gemfields mines the potential emerald-bearing contact zones, which can vary from a couple of centimeters to a couple of meters. Exposed emerald crystals are removed by hand tools and sent to the sorting plant. The materials in the rest of the contact zone are loaded by the excavator into trucks and taken to the processing plant for recovery of any emeralds not seen and removed by hand tools.

Miners chisel the reaction zone rock to recover any emeralds it might contain. The chiseling

and recovery are supervised by geologists and security staff. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Daytime operations are reserved for production mining by Gemfields personnel of the phlogopite-magnetite schist contact zones. Daylight provides the best visibility for recovering emeralds by hand chiseling, and for security to minimize the possibility of theft. The strip-and-fill operation takes place before and after production mining.and recovery are supervised by geologists and security staff. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

The hard-rock overburden stripped away by the contractor and in-house fleet is used to fill in an area located at the opposite end of the pit that is already mined and exhausted—an area called the footwall. This helps to reduce the overall size of the pit and to keep environmental liability costs down. It also makes sound economic sense in that the shorter the distance they have to transport material, the lower the overall cost of mining per ton. The key to the strip-and-fill method is to find the right balance between waste rock removal and contact zone mining for the optimum continuing recovery of emerald.

The pit at Kagem is enormous. Its pushback wall is on the left, with benches. The footwall opposite that is filled in as new mining takes place. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

To protect the emeralds, Gemfields blasts the talc-magnetite schist and the pegmatite separately, but never the contact zones. The excavator then removes enough material to expose the contact zone for the recovery crew, called chiselmen. After excavators open up a contact zone, the team of chiselmen comes in with security personnel and chisels materials in the contact zone to recover the emeralds. Chiselmen have years of experience to guide them during this entirely hand-powered operation.

Blasting is an essential part of the mining operation. It begins the process of creating pushbacks to allow chiseling and ore removal. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Security and supervisory staff are always present during hand-chiseling of the exposed contact zone to recover the emeralds. This not only helps to secure the emeralds from theft but also helps to provide complete transparency of recovery. Any production found goes into a locked production box. The geology staff and security staff have keys to the boxes, which are secured and transported to the sorting house. Cobbing to remove schist from the emerald crystals is done at the sorting house and not at the pit. The mining process is designed to handle as much rock as possible while also taking care to not damage any crystals and to ensure the security of the recovered emerald crystals.

Chiseling for Treasure

Kagem monitors every piece of equipment for operational efficiency and surveys every ton of rock. Material from every contact zone is documented by location and production, and that documentation stays with it through final sorting of the emerald it yields. Every pushback and every sector of the pit is documented for amount of waste rock, number of contact zones, and production level, including quantity and quality of emerald. This information helps them project production for the next pushback.Gemfields’ five-year plan for the future involves removing the waste rock from the fourth pushback and mining the exposed contact zones. While colored stone mining recovery rates and qualities cannot be precisely projected, historical data can be used to estimate future production. The current mining and pushback plans were formulated in 2013.

To allow for the possibility of future additional exploration in key target areas, Gemfields doesn’t re-fill all of its mined pits. Instead, they leave them open and allow water to accumulate in them. To offset the carbon footprint, the mine’s waste areas are rehabilitated by covering them with soil and planting trees. The company’s goal is to practice sound, profitable mining that leaves the environment in a better state than when they found it. When Gemfields took over the mine six years ago, it had an environmental liability of more than $5 million. Today, that environmental liability has been brought down to around US$350,000.

Mining operations in Zambia have to contend with the wet conditions in the area. Although our visit was during the dry season, there was still water in the pit, due primarily to the presence of natural groundwater. During the rainy season, substantial rainfall fills areas of the pit with water and raises the groundwater level. Gemfields has planned the pit so the excessive water that accumulates during the rainy season will pool in the deepest areas, which are not being mined, while mining is going on in the more high-lying areas. Even so, Gemfields still uses large amounts of diesel fuel to operate the pumps that remove the water from the pits during the rainy season. The mud and constant rains make mining more difficult, but it can still be continued throughout the year. Smaller mining operations simply cannot afford the equipment needed to remove the water, so they often stop mining during the November to March rainy season.

There is always some water from rain or groundwater seepage in the pit. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

At Kagem, the geology department is intimately involved in planning and mine operation. As with Gemfields’ Montepuez ruby mine in Mozambique, they embrace the philosophy that geology dictates the mining. Another department is responsible for security and safety, and ensuring the highwalls are at the proper angles to be safe and secure.

Strip-and-fill Mining

Underground Exploration Pilot Project

For more than five years, Gemfields has been experimenting with a pilot underground operation. Its scale is not suitable for production, but they have learned a lot about the feasibility of an underground mine. Considering the extent of the underground ore that Gemfields now knows to exist, they will continue to pursue this project. Gemfields will increase the scale of underground operations as they learn more and get a better sense of its potential. The underground mining pilot project is being used along with the drilling project to better understand the entire deposit and how to successfully mine it.

To reach the working galleries, the underground mine starts with stairs leading to a

decline ramp. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Historically, Zambian emerald mining has always been done by the open-pit method. This is due partly to a number of local challenges to going underground, such as the amount of water in the area. While we were in the pilot underground mine, we observed that water was constantly dripping from the tunnel walls. The underground water level is generally high, but it is even higher during the rainy season. Thus far, Gemfields has been able to handle the water in the experimental mine.decline ramp. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

The pilot project looks at a number of unknown factors when deciding on techniques to be used for underground mining, including ventilation, rock supports, water seepage, and geology. The project started with a decline tunnel and within 5 meters they were into the talc-magnetite schist.

We went 30 meters down the current decline shaft and through horizontal tunnels to where the quartz-tourmaline and quartz-feldspar pegmatites vertically intersect the talc-magnetite schist, and the emerald-forming contact or reaction zones are seen. Over the last five and a half years, Gemfields has developed over 950 meters of underground mining, consisting of narrow tunnels and crosscuts. Every square meter of the underground operation has been surveyed and roof-bolted for safety. All the tons of rock removed were catalogued as part of the learning phase for future potential underground production.

Kagem Senior Geologist Robert Gessner explains the geology of Zambian emerald by showing formation zones in the underground mine. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Currently, Gemfields is using a rope and pulley system to haul the material out of the tunnels in bags. This system is cost effective but labor intensive. It has worked fine for the pilot learning project but would be a bottleneck if used for full commercial production. Over five and a half years, all 950 meters of this underground project have been worked by 19 miners drilling, removing, loading, and hauling the material out. The underground operation removes 20 tons of contact zone material a day. For comparison, a single truck in the open-pit operation removes that much material five times every hour.

While the underground ore is currently being removed by a pulley system, it will be

necessary to develop a system that allows for a far greater production capacity when

the project goes into full commercial production. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

The key to expanding the underground mine from a pilot project into production is to duplicate the production capacity of the open-pit mine, which is around 8,000 tons of ore a month. This would only be made possible by increasing the scale of the operation, installing a proper production hauling system, and engineering to support these larger systems. Columns are needed to support underground operations in mined areas as well as areas that are not being mined. Currently the main tunnel is 2x2 meters. To expand for production, the tunnels would need to be at least 6x3 meters. The future vision is to have a decline ramp where trucks could drive in and be loaded with ore as it’s removed from horizontal tunnels.necessary to develop a system that allows for a far greater production capacity when

the project goes into full commercial production. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Robert Gessner said that one of the big differences between the open pit and the underground operation is that in the open pit, even though all the ore goes to the washing plant, 65 percent of production is achieved in the pit and 35 percent through recovery at the washing plant.

For this pilot project as well as any future underground operations, all the ore will still go to the washing plant, but due to the fact that there is more contamination, the majority of production—about 80 percent—will be achieved at the washing plant before the ore goes to the sorting house. With this in mind, Gemfields has focused on expanding the capacity of its washing plant.

While this pilot project is ongoing, new open pits are expected to come into production in the future as a result of ongoing prospecting and exploration. This means open pit production is expected to continue to be the main source of Kagem emeralds for many years.

The current tunnels would have to be significantly expanded in order for the underground

operation to reach production levels anywhere near those of the open-pit operation.

Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

The underground operation is still in its experimental stages. However, the geology is more clearly visible in the underground tunnel. As additional tunnels are opened, they will add important information that can be used for other exploration projects.operation to reach production levels anywhere near those of the open-pit operation.

Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Prospecting and Exploration

Extensive prospecting and exploration are the keys to ensuring and securing the production and life of a large-scale mechanized mine like Kagem. Gemfields has invested a lot of capital in both core drilling and bulk sampling since it took over the mine.Since emerald prospecting in the Kafubu area has never paused in the past 100 years, earlier investigations formed a solid base for current and future work. Prospecting’s main goal is to better define the underground distribution of the ore-bearing schist and the quartz-tourmaline veins. Meanwhile, the exploration also allows the geologists to form a better estimate of how much waste and ore they need to handle to recover the emeralds. In earlier stages, both magnetic and radiometric surveys were used to locate the talc-magnetite schist and the quartz-tourmaline veins. Since the schist contains magnetite, it has a higher magnetic reactivity than other rocks in the area. The presence of certain elements in pegmatites and quartz-tourmaline veins allows them to be picked up by radiometric surveys.

After the location is targeted, finer resolution methods like core drilling, petrographic analysis, and geochemical analysis are applied to more accurately delineate the talc-magnetite bodies and the quartz-tourmaline veins. For the past three years, intensive core drilling and bulk sampling have been done by the mine’s exploration team within selected areas.

In addition to the big pit, Kagem has developed several bulk-sampling pits. Some of them will be in production in the near future. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

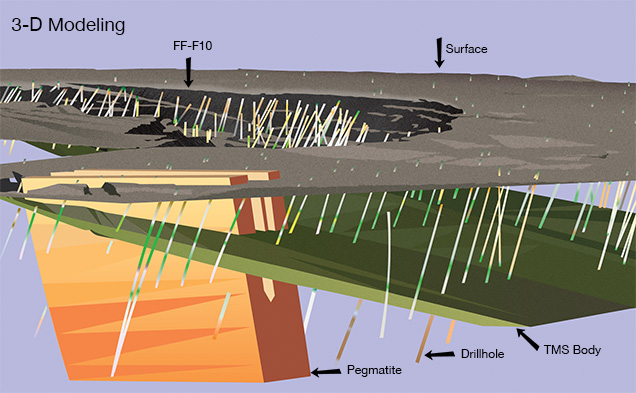

In the core library at the Kagem mine, thousands of boxes are stacked in the two storage rooms. Senior Geologist Robert Gessner explained that, for the past three years, Gemfields had done a huge amount of core drilling in some potentially productive areas within its property. The total drilling length is about 36 kilometers. Exploration teams work two shifts per day, six days per week. They must complete 30 meters of hard-rock drilling each day.After the core is removed, petrographic work and geochemical analysis are applied to the talc-magnetite schist body. The concentrations of trace elements chromium and vanadium were measured using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. The drilling cores are studied meter by meter and all the data is input into a geological three-dimensional modeling program called SURPAC to help construct a 3-D model of the underground geology. The modeling is focused on the distribution of the talc-magnetite schist and the reaction zones where emerald mineralization takes place.

After completing thousands of core drillings, geologists use the data to construct a 3-D model of the host rocks and the pegmatites below the earth’s surface. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

Every drill core is important as a reference for future mine planning, so they are all very well catalogued and preserved as individual sample assets. Mine personnel can easily access them for further study. The cost of core drilling is $500 per meter. The total amount that Gemfields has invested in this process is tremendous, but it’s a necessary expense for starting any serious mining project and allowing the miners to understand as much as possible about the geology of the area. It also helps them determine the most cost-effective mining technique. As Robert Gessner repeatedly said, “Mining is dictated by the geology.”

Core Library

After core drilling and geology modeling are done, the real digging begins. This is the pre-production stage called bulk sampling. As the geologists say, you can never be sure about the geology until you open and sample the pit. Excavators are used to open a bulk sampling pit. The property contains six potentially productive areas that need to be explored in addition to the big open pit now in production. Our team visited two of those potential pits, Fibolele and Libwente.

Fibolele is one of Kagem’s bulk sampling pits. All bulk sampling pits are tightly secured by a 24/7 patrol of security staff and dogs. Photo by Stanislas Detroyat.

When Vincent Pardieu visited the mine in 2011 and 2012, exploration and sampling of Fibolele had just started. The wall of this “baby pit” has been continually pushed back over the past two years. The goal of the bulk sampling projects is to determine the potential for a second open-pit operation. Security is tight at the testing pits. Guards and dogs patrol them 24/7, since the loss of any pockets of stones can change the project’s determination from profitable to unprofitable. At the time of the authors’ visit, this pit was showing a good return rate.Later, during our visit to the sorting house, we saw some interesting samples of promising quality coming from Fibolele. We were able to select some of these samples as reference specimens for the GIA Laboratory. We were told that, due to the promising results from phase-one sampling, this pit is now engaged in phase two of bulk sampling.

The authors visited another bulk sampling pit at the concession, called Libwente South. Gemfields has done about 17 kilometers of core drilling in this area, and results indicate great potential. In the three months before the authors’ visit, mine operators were working on removing the topsoil, and the teams are now trying to find a balance between mining costs and return. This pit will be in production in the very near future. Standing on the edge of the pit, the authors were able to clearly see the part of the quartz-tourmaline veins and the talc-magnetite schist bodies that have been exposed.

The Libwente South exploration pit is currently still in its early stages, but exploration results have shown that it has great potential. Photo by Stanislas Detroyat.

Production

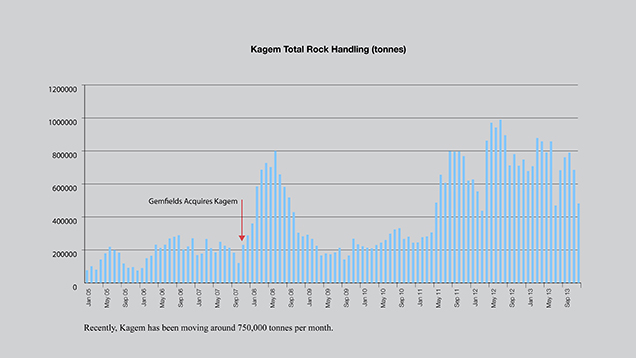

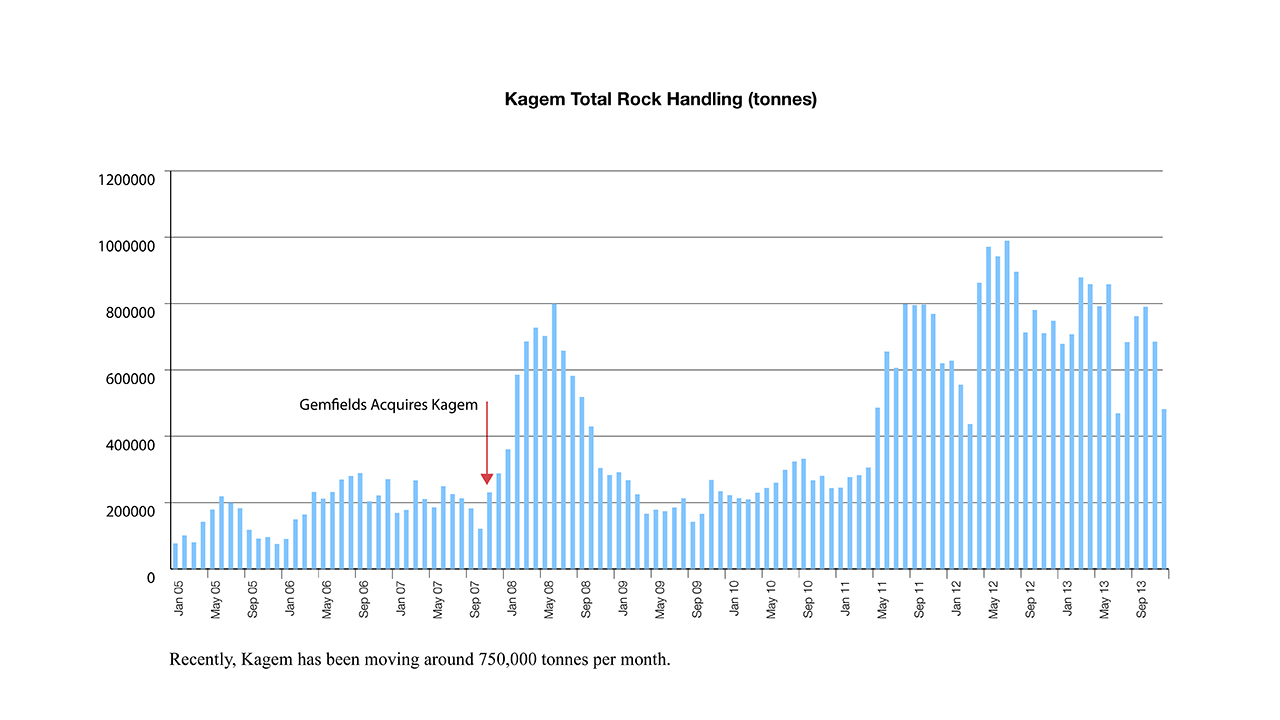

The phlogopite-biotite contact zones are associated with two pegmatites, a quartz-tourmaline pegmatite and a feldspar-tourmaline pegmatite. The better-quality emeralds are associated with the contact zones at the reaction areas with the quartz-tourmaline pegmatite. Gemfields auctions are broken into two quality ranges: one auction for lower-grade material and one auction for higher-grade material. The charts below show Kagem production amounts in terms of rock handling and total gemstone production since January 2005.

Rock-handling Totals

Production Levels

Expedition guest Stanislas Detroyat displays an emerald crystal from among the sorted

parcels of emeralds recovered from the pit. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

parcels of emeralds recovered from the pit. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Washing

Operations at the processing plant involve ore crushing and washing, with no introduction of chemicals. A triple-decker screen breaks the material down by size and final pickers pick out the emerald crystals by hand under the watchful eye of security.

The large quantity of production is evident at the Kagem mine when you see truck after truck removing ore from the pit for transport to the washing plant. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Once the ore is transported to the washing plant, it follows a process that is typical of sophisticated colored gemstone mining operations. Screens are used to break down the material by size and then washers remove the silt to expose the potential emerald-bearing schist for hand pickers to examine.During our visit we observed various interesting improvements that Gemfields has implemented in their washing plant, which was renovated in December 2013. The picking area was enclosed and the lighting and security environment improved. Its capacity is currently 40 tons per hour, but now it can operate 24/7 with three eight-hour working shifts, while during author Vincent Pardieu’s last visit it was only working two eight-hour shifts. Low-quality material is processed at night, while higher-quality ore is sent to the washing plant during the day. The plan is to continue improving the process in order to reach 150 tons per hour. When they reach that capacity, the Kagem washing plant will be able to absorb the quantities expected to be produced from new pits like Fibolele and also the underground operation when it reaches production level.

The Washing Plant

Sorting and Grading

Opening the safe box is the first task for Kagem’s sorting house staff. Different-sized boxes are used for ores or stones of different sizes. Emerald-bearing ores can be transferred directly from the open pit, from the underground mining operation, or from the washing plant, and each safe box has four locks to secure the stones inside and to allow for the assignment of security responsibilities to different departments. It can be weeks or even months between the time a box is opened and the time a stone is referenced. Very strict rules are applied at each step, throughout the entire process. Weight is checked at each step, and waste is retained to make sure the total weight is consistent.

Gemfields takes security very seriously. Each safe box has four locks to protect the interests of all parties. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

According to sorting house staff, they process about 200 kg of ore per day, for a total of 20 to 30 tons a year. Lower-quality materials are cobbed first to remove overburden, while the higher-quality materials are individually cleaned by high-pressure air.

Cobbing is an art and a very important step that removes highly included areas from

the emerald rough. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

In the sorting house, staff members do their best to recover every piece of emerald. The authors were introduced to a newly designed and installed in-house washing system by Mr. Etienne Marvillet, the mine’s production manager and one of the system’s designers. This machine’s operation is similar to the machines in the washing plant but on a much smaller scale designed to handle finer materials. It is a very handy tool for the sorting-house staff because it allows them to process the material onsite without going back to the washing plant. This also decreases the security risk and the total potential loss.the emerald rough. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

A first step in the process is to remove the emeralds from the schist. Photo by Vincent

Pardieu/GIA.

Gemfields’ ability to deliver quality parcels for auction is directly related to the quality of their reference sets. Gemfields has three reference sets, one at the sorting house at the Kagem mine in Zambia, one in India, and one in the UK. The reference sets were built from production at various locations in the mine over a number of years. This is a highly important aspect of the grading system, as incorporating older stock into the system helps to ensure consistent grading as new production comes forward.Pardieu/GIA.

The grading system is internal to Kagem production and has been a key to the success of their auctions. Buyers have come to trust the grading of the parcels and rely on them to be consistent over the years. Gemfields does not believe in offering mixed-quality mine runs in huge parcels. They believe their customers and shareholders are better served by offering properly graded parcels covering all their production grades.

This grader must determine the quality of this large emerald crystal so it can be

accurately represented at auction. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

The grading set has six size classifications that represent the range of sizes coming out of Kagem production. Size classification is important since small stones are often less included than larger ones. The production is then further classified by separating material with a strong blue secondary modifying hue from the purer green material. After the production is graded to this point, more stringent grading procedures refine it into further classifications. Gemfields then evaluates the color, clarity, and transparency. For transparency, graders separate cleaner facet-grade material from hazy material used for cabochons and beads. Once the stones are placed into purer green or modified-by-blue categories, they are graded into about 14 additional classifications.accurately represented at auction. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

The reference set allows for the consistent grading that has a lot to do with the success

of Gemfields auctions. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

of Gemfields auctions. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Collecting Reference Samples

In the Summer 2014 issue of Gems & Gemology, GIA researchers—including the Bangkok lab’s Vincent Pardieu—published a preliminary study on the three-phase inclusions in emeralds from different sources. They studied a selection of samples from the GIA global reference collection, including stones from the Kafubu area. The study was part of GIA‘s ongoing research on the determination of colored stone origin, with a focus on emerald, ruby, and sapphire. This research has taken place under the direction of the GIA Bangkok lab since 2008.

The ultimate goal for a field gemologist is to dig reference gemstone samples right out of the ground themselves while completely documenting the location and circumstances. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

The first day of our visit to the Kagem mine, we were taken down to the bottom of the large open pit. Miners were using an excavator to remove the ore from a local shear zone and we were allowed to pick emerald samples from the removed material. Vincent Pardieu collected several samples that were still in their matrix. All had outstanding color and transparency. Tao Hsu found a large emerald crystal with nice color and shape. Later, Vincent and Tao followed the big stone to the sorting house and witnessed it being cleaned. The rest of the samples will be kept in their matrix and shipped by Gemfields to the GIA Bangkok lab for further study.

As Tao looks on, a member of the sorting house staff uses a high-pressure air tool to

clean quality samples. The sample he’s working on is the one Tao collected earlier in

the day and it’s destined for the GIA reference database. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

During this visit, members of the group also collected samples from other mining operations in the Kafubu area. When researchers collect samples onsite and can verify that they came directly from the pit, the samples are considered type A samples—the most valuable category for research purposes. This and future collection expeditions will help to enrich the GIA reference collection. More complete studies based on these samples will be presented in future Gems & Gemology and GIA web articles.clean quality samples. The sample he’s working on is the one Tao collected earlier in

the day and it’s destined for the GIA reference database. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Preliminary Gemology

As with all emeralds, Kagem emeralds owe their rich green color to the presence of chromium and vanadium. That color is often modified by iron, which is commonly present in emeralds mined from pegmatites intruding into schists. The presence of iron is detected by chemical analysis using EDXRF or LA-ICP-MS, but also by studying UV-Vis spectra.Kagem emeralds form in a reaction zone within a quartz-tourmaline or quartz-feldspar pegmatite. With the presence of some talc, magnetite, and mica-rich schist, mineral inclusions of magnetite, mica, quartz, feldspar, or tourmaline are common. As fluids play an important role in the formation of these emeralds, they most commonly contain multiphase inclusions. The inclusions usually consist of a liquid and a gas bubble, and often a solid doubly refractive crystal.

There’s more information about the gemological characteristics of emeralds from the Kagem mine, and about methods the GIA Laboratory can use to separate them from emeralds from other deposits, in an article about emeralds with multiphase inclusions published in the Summer 2014 issue of Gems & Gemology.

Inclusions in Emerald

Mine Security

After the size of the pit, the next thing that struck us at Kagem was the level of security. According to a member of the security staff, there are 150 security guards and 50 security dogs working around the entire mining concession. When miners are in the pit, there are always two security guards monitoring the operation. The chiselmen were closely monitored as they removed the emeralds from the pit and placed them in the lock boxes.

Management and security personnel watch over the workers as they chisel the rock and place emeralds into the red lock boxes. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Everyone who leaves the pit undergoes a vehicle, bag, and body search. This includes visitors, Kagem staff, and Kagem management regardless of level. Security checks also occur at the washing plant and the sorting facility, as well as when you leave the mine grounds. The security procedures are applied evenly to everyone that goes through the check points. Closed circuit television monitoring also takes place in the sorting house.

Mine Security

Even with all that security, we still saw some people, described by the mine staff as illegal miners, trying to retrieve emerald-containing pieces of ore from the license areas and mine dumps. In the days following our visit, Vincent Pardieu, Stanislas Detroyat, and Didier Gruel spent several days visiting other emerald mining operations in the Kafubu area. During those visits, they met several of those individual miners, either in the early mornings as they returned from a long night of prospecting, or in the evenings when they were just setting out. Indeed, it seems that hundreds of people cross into the Kagem mine to look for emeralds. According to them, their main market is local or foreign merchants (mainly from West Africa), who wait for them each day in nearby villages or in Kitwe. Interestingly, among the most powerful tools used by these illegal miners and traders are mobile phones, which is why mobile phones are not allowed inside the Kagem operation.Gemfields and Kagem

Gemfields places great importance on the people involved in its Kagem mining operation. They devote a lot of time and effort to finding, recruiting, and keeping talented and highly motivated people with passion for their work. Gemfields also believes in developing people and helping them advance into higher positions and further the company as they further themselves. The working environment is very much focused on a team effort.

The Kagem operation provides employment and skill development for locals in a number of positions at the mine. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Another Gemfields advantage is the working capital they invest in properly running the mining operation. This allowed initial investment in equipment and the ability to spend a year cleaning the pit so the proper mining methodology could be implemented. By bringing in the proper equipment, building suitable structures, applying the correct techniques, and training the staff, Gemfields has been able to turn local employees, who were highly unmotivated under previous management, to being highly motivated.People from the Kagem mine state that since Gemfields took over and started producing, the mine has been profitable for the first time in its life. After its first 19 years, Gemfields came in and turned it into a profitable mining operation in just six years.

The Kagem mining operation is a colored stone mining project combining heavy investment with a high degree of sophistication. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Gemfields is a publicly traded company on the London Stock Exchange. It is a subsidiary of Pallinghurst, another publicly traded company with very strong experience in platinum mining. Gemfields owns 75 percent of the Kagem operation. The other 25 percent is owned by the Zambian government. The Kagem mine is the only operating emerald mine in Zambia that shares a percentage ownership with the government. Gemfields took over their 75 percent share from the previous management.Since it’s a publicly traded company, Gemfields’ corporate strategy boasts a high level of transparency—a quality that is not universal in the colored gemstone industry. This transparency has helped build the company’s relationships with its government partner at Kagem as well as with employees, shareholders, and the rest of the colored gemstone industry. The Zambian government has representatives on the Kagem board, including the chairmanship.

Community Relations and Employees

Gemfields has an active program devoted to evaluating local agricultural, educational, health, and cultural factors such as chiefdoms. The company works with local communities to identify ways of improving these components in a program devoted to social beneficiation.The company has assigned a full-time community project coordinator to work onsite to implement the program. Securing the food supply is probably the most important factor in many local communities. The Kagem operation fully supports two local farms, helping those local farmers support their own families, sell their products, and provide fresh vegetables to the mine.

Local farmers benefit from support by Gemfields’ Kagem mine. They can sell the

vegetables they produce in local markets and also for serving in the mine kitchen.

Photo by Robert Gessner.

To support basic education of the local population, Gemfields has provided a school and teachers’ quarters, while the Zambian government provides the teachers. A budget of $1.2 million has been approved for a two-year project to build a secondary school and health center in an area where none existed. The health center serves 5,000 local people. Children’s and maternity wards are also being developed.vegetables they produce in local markets and also for serving in the mine kitchen.

Photo by Robert Gessner.

Community Projects

A large part of Gemfields’ relationship with the local community comes from employing locals and training them in skills that prepare them for the future. New hires get a five-year contract rather than the two-year contract that is more normal for mining staff. Employees are bused in every week and taken home at the end of the week. Accommodations and meals are provided onsite and employees and their immediate families get medical coverage. Kagem is also proud of its safety record of over 3 million man-shifts without an injury.

Kagem’s excellent safety record is recognized by the Mines Safety Department of Zambia.

Courtesy Gemfields.

Gemfields’ Kagem operation currently has about 570 employees. About 50 expats hold most of the management positions. However, Gemfields is dedicated to training local employees to improve their skill levels in hopes that they will eventually take management positions and run the operation. Opportunities in Zambia for locals to become mining engineers and geologists are limited, but Gemfields’ goal is to train local employees in those professions.Courtesy Gemfields.

Kagem trains its local employees to help them gain mining skills that will benefit the

future of Zambian mineral resources. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

future of Zambian mineral resources. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

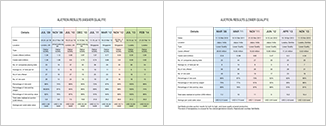

Auctions

Gemfields’ operational transparency is reflected in its auction system. Auction sales results are public knowledge, providing assurance to the Zambian government that they are being informed about actual production revenue and that the production was sold at market value. The auctions also provide complete revenue transparency to shareholders. Many in the colored gemstone industry find the Gemfields auction system to be a very transparent and fair way to offer rough gemstones for sale. All trade members invited to the auctions have an equal chance of acquiring the rough parcels they need.

Gemfields provides auction results for both its high- and lower-quality emerald production. This level of transparency is unusual for the colored gemstone industry. Reproduced courtesy Gemfields.

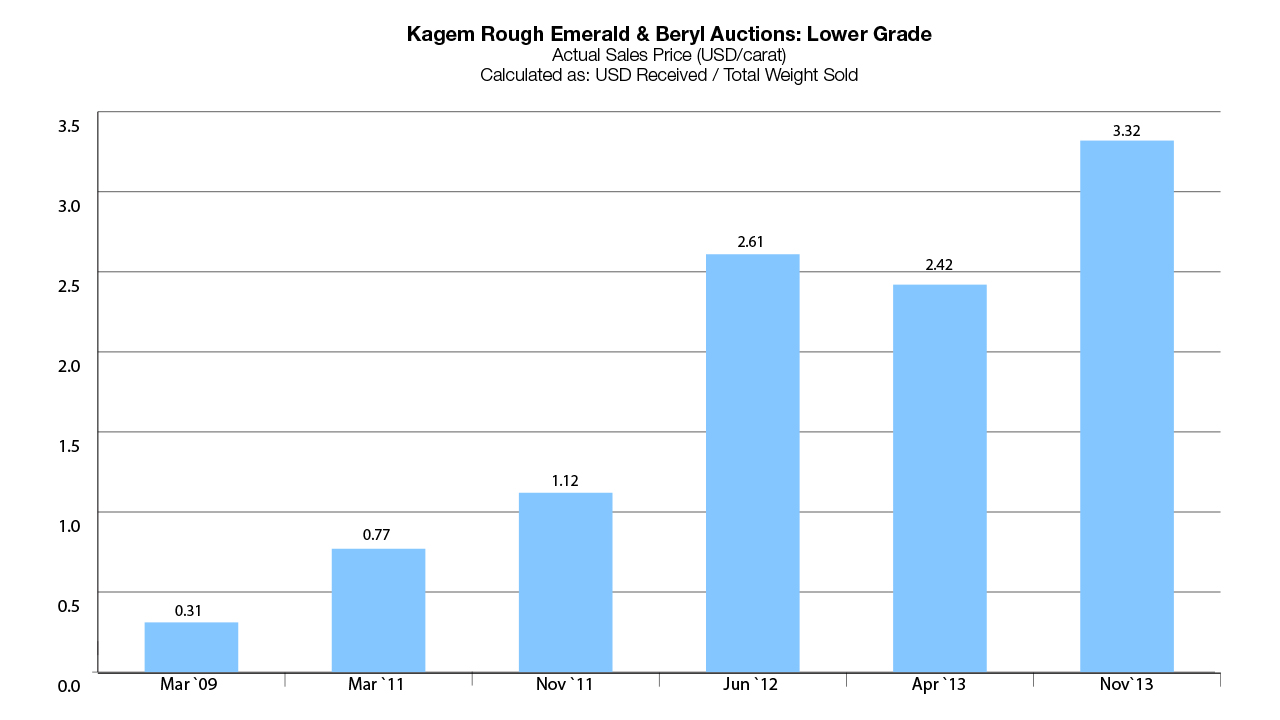

A key factor in the auctions’ success is the consistent sorting and grading of the rough emerald parcels that takes place at the mine. Over the years, Gemfields has had feedback from auction buyers regarding their needs, and those buyers have come to trust the consistency of Gemfields grading. In addition, customers who bought a certain grade several years ago can be confident that they can bid on a parcel with the same grade at a future auction and be able to match the stones from both. The auctions also create a sense of trust in that everything is on the table and there are no behind-the-scenes deals.Revenue per carat has been consistently rising over the last six years at both the high- and low-quality material auctions. This increase in the per-carat price has helped to ensure that the revenue per mined ton is higher than the per-ton cost. This is a critical calculation for the continued profitability and sustainability of the mine.

Per-carat Prices

Summary

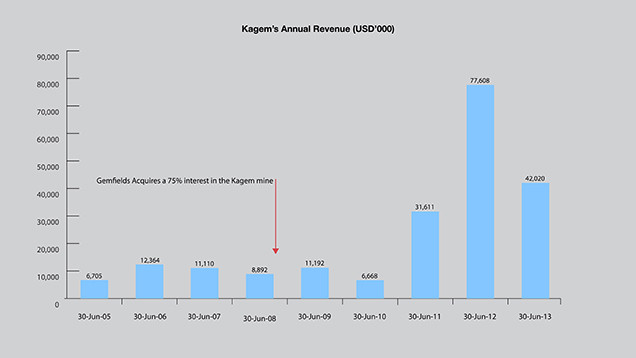

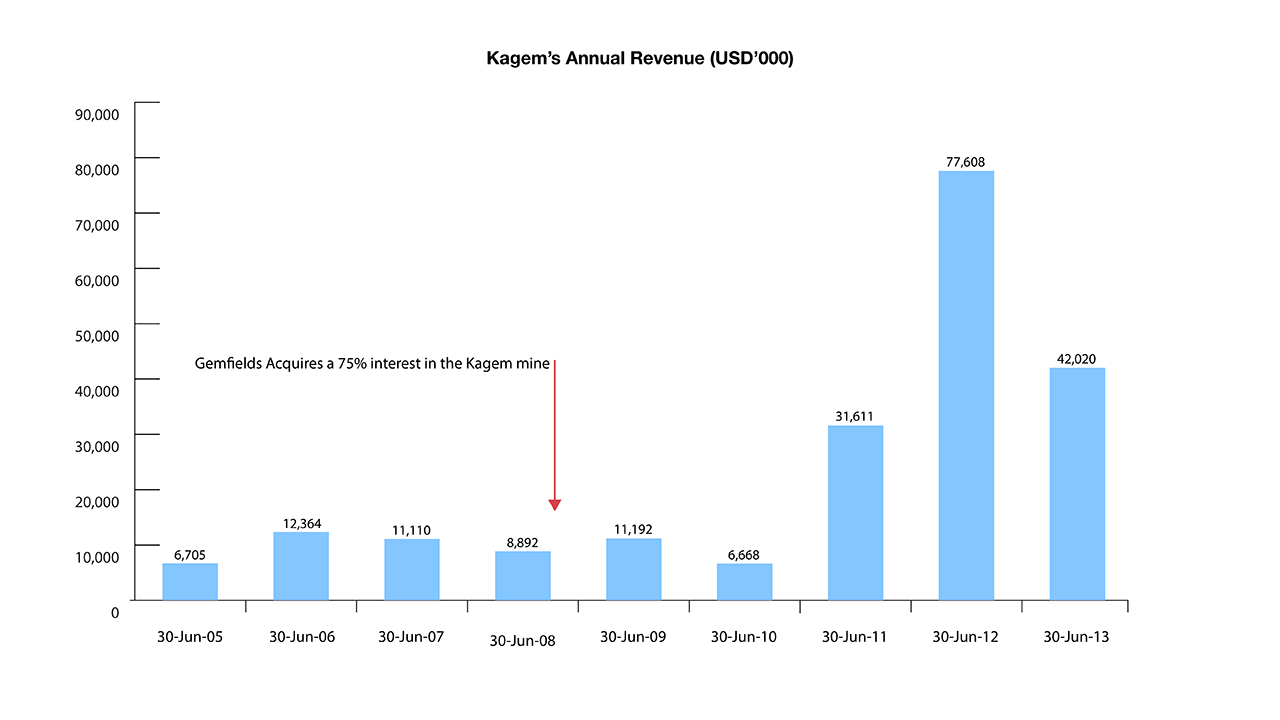

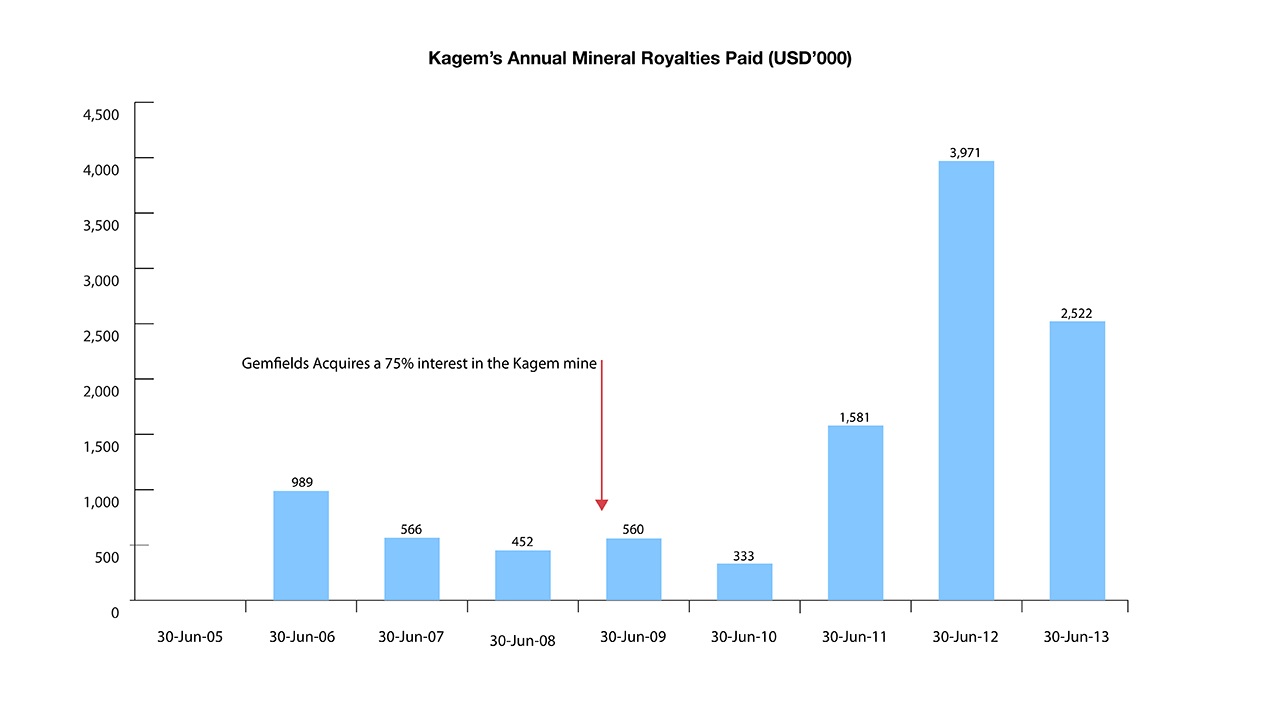

Gemfields has achieved impressive results at the Kagem mine so far. They have taken the mine from a long history of loss and turned it into a profitable venture for all parties. The annual revenue has increased and the mine is now profitable and paying increasing royalties to the Zambia government. They have demonstrated that proper mining methodology, community relations, environmental protection, transparency, and government partnerships actually improve the gemstone mining business. But the impact of this mining operation probably goes far beyond just the results obtained at this mine.Gemfields has shown that proper funding, wisely invested in the right mining property, can result in profits. As a publicly traded company, they have also made an important contribution to the movement to attract investors into the colored gemstone industry. Their auction system has been a success in terms of customer acceptance and satisfaction, transparency for all parties, increases in per-carat value, and company profitability. The Kagem mine is a remarkable example of the right combination of geology, mining methodology, innovative business strategies, best business practices, and marketing.

Kagem’s Revenue, Royalties, and Profit

About the Authors

Dr. Tao Hsu is the Technical Editor of Gems & Gemology. Andrew Lucas is Manager, Field Gemology, for Content Strategy at GIA Carlsbad; Vincent Pardieu is Senior Manager of Field Gemology at GIA Bangkok. Robert Gessner is Senior Manager Geology for Kagem.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Gemfields and the Kagem mine, including Ian Harebottle, CEO; Adrian Banks, Product Director; Robert Gessner, Senior Manager-Geology; and Etienne Marvillet, Product Manager.