Exploring the Chinese Gem and Jewelry Industry

ABSTRACT

In the wake of its phenomenal economic growth since 1978, China has captured the attention of the global gem and jewelry industry. Already a global hub for jewelry manufacturing, it is now a rapidly growing consumer market. While rising costs of labor in China have created challenges for the manufacturing sector, this has led to greater domestic consumption of luxury products, including jewelry. The highest growth potential lies in the inland urban centers, as Chinese citizens continue a massive migration from rural areas to the cities. Chinese consumers are becoming more knowledgeable about gemstones and jewelry and more astute in their purchases. They have a keen sense of both value and brand trust, and they have become more open to contemporary and Western designs and materials. At the same time, technological advances in manufacturing are leading to higher quality standards and lower labor costs, allowing China to meet the increasing demands of the global and domestic markets. Although the recent global economic crisis has affected domestic sales, the Chinese gem and jewelry industry shows great potential for growth.

INTRODUCTION

The West’s fascination with China as an economic powerhouse is equaled by the tremendous opportunities found there. The title of a 2004 New York Times article, “The Chinese Century,” summed up the widespread sentiment that China will become the world’s leading economic power and most influential country early in this century (Fishman, 2004). The same holds true for the gem and jewelry industry: For years a global manufacturing hub, China is emerging as the strongest consumer market for luxury products such as jewelry.

Chinese consumers are now synonymous with luxury products, and this is true with gemstones and jewelry. The Chinese market is the new focus for luxury and glamour for many types of jewelry (figure 1). Although the explosive growth of the last three decades is predicted to slow, domestic consumption and discretionary spending is expected to rise. These trends, along with rapid urbanization, a burgeoning middle class, and a younger generation of sophisticated shoppers, signals exciting opportunities for China and the global gem and jewelry industry. This requires China to address new challenges, such as sourcing enough gemstones to satisfy import and export demand (figure 2).

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

In 2010, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy after the United States (table 1). Overall, China’s annual growth rate has averaged around 10% over the last 30 years (Barnett, 2013). According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the gross domestic product (GDP) growth for the first half of 2013 was US$4 trillion, a year-on-year increase of 7.6%. Bloomberg senior economist Michael McDonough correctly predicted that the government would tolerate much slower growth in the second half of 2013, as its strategy shifts to more sustainable long-term growth (Zheng, 2013).

| TABLE 1. GDP by country, 2012. | ||

| Adapted from the World Bank (2013). | ||

| Ranking | Economy | Trillion US$ |

| 1 |

United States

|

15.684 |

| 2 |

China

|

8.227 |

| 3 |

Japan

|

5.959 |

| 4 |

Germany

|

3.399 |

| 5 |

France

|

2.612 |

| 6 |

United Kingdom

|

2.435 |

| 7 |

Brazil

|

2.252 |

| 8 |

Russian Federation

|

2.014 |

| 9 |

Italy

|

2.013 |

| 10 |

India

|

1.841 |

A 7.6% predicted growth may seem low compared to the years of double-digit growth over the past three decades, but it is still quite enviable when compared to growth rates in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. The predicted growth rate is certainly very respectable for the world’s second-largest economy, with a GDP over $8 trillion (table 2). Some analysts predict that China will overtake the U.S. as the world’s leading economy sometime between 2020 and 2030 (Shamim, 2010), while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has predicted this will happen before 2020. The timeframe is ultimately dependent on the future growth rate, which is predicted to slow.

| TABLE 2. Economic growth of China, 1979-2012 | ||||

| Data compiled from World Bank (2013) and Gemmological Association of China (2013). | ||||

| Year | GDP (trillion US$) | GDP increase (%) | GDP per capita (yuan) | Discretionary income per capita (yuan) |

| 1979 | 0.1766 | 7.6 | 419 | 387 |

| 1980 | 0.1896 | 7.8 | 463 | 477 |

| 1981 | 0.1941 | 5.2 | 492 | 491 |

| 1982 | 0.2032 | 9.1 | 528 | 526 |

| 1983 | 0.2284 | 10.9 | 583 | 564 |

| 1984 | 0.2574 | 15.2 | 695 | 651 |

| 1985 | 0.3067 | 13.5 | 858 | 739 |

| 1986 | 0.2978 | 8.8 | 963 | 899 |

| 1987 | 0.2704 | 11.6 | 1,112 | 1,002 |

| 1988 | 0.3095 | 11.3 | 1,366 | 1,181 |

| 1989 | 0.344 | 4.1 | 1,519 | 1,373 |

| 1990 | 0.3569 | 3.8 | 1,644 | 1,510 |

| 1991 | 0.3795 | 9.2 | 1,893 | 1,700 |

| 1992 | 0.4227 | 14.2 | 2,311 | 2,026 |

| 1993 | 0.4405 | 14 | 2,998 | 2,577 |

| 1994 | 0.5592 | 13.1 | 4,044 | 3,496 |

| 1995 | 0.728 | 10.9 | 5,046 | 4,283 |

| 1996 | 0.856 | 10 | 5,846 | 4,838 |

| 1997 | 0.9526 | 9.3 | 6,420 | 5,160 |

| 1998 | 1,0195 | 7.8 | 6,796 | 5,425 |

| 1999 | 1.0833 | 7.6 | 7,159 | 5,854 |

| 2000 | 1.1985 | 8.4 | 7,858 | 6,280 |

| 2001 | 1.3248 | 8.3 | 8,622 | 6,860 |

| 2002 | 1.4538 | 9.1 | 9,398 | 7,702 |

| 2003 | 1.641 | 10 | 10,542 | 8,472 |

| 2004 | 1.9316 | 10.1 | 12,336 | 9,421 |

| 2005 | 2.2569 | 11.3 | 14,185 | 10,493 |

| 2006 | 2.713 | 12.7 | 16,500 | 11,759 |

| 2007 | 3.4941 | 14.2 | 20,169 | 13,786 |

| 2008 | 4.5218 | 9.6 | 23,708 | 15,781 |

| 2009 | 4.9913 | 9.2 | 25,604 | 17,175 |

| 2010 | 5.9305 | 10.4 | 29,748 | 19,109 |

| 2011 | 7.3219 | 9.2 | 35,083 | 21,810 |

| 2012 | 8.2271 | 7.8 | 38,354 | 24,565 |

Manufacturing. China became the world’s largest manufacturing economy (figure 3) in 2010 and in 2012 widened its lead over the U.S. with $2.9 trillion in manufactured goods annually, compared to $2.43 trillion from the U.S. (Sims, 2013). A major factor behind this has been China’s surge in domestic consumption (Chen, 2013).

Urban Centers. Chinese cities are generally divided into four tiers. First-tier cities (figure 4) are the most developed and cosmopolitan urban centers; these include Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. The other tiers represent cities with less wealth, lower wages, less discretionary income, less infrastructure, fewer amenities, and fewer resources. Unofficially, there are 59 cities in the second tier, 92 in the third, and 105 in the fourth (Schuster, 2012).

Second-tier cities are rapidly developing into commercial centers, and this is reshaping the country’s commercial, industrial, and regulatory landscape (Schuster, 2012). With rising costs of labor and land in first-tier cities, manufacturing has moved into second-tier cities and continued into the lower tiers. Government reforms have helped fuel this development. As jobs are created and more resources are allocated into these emerging cities, consumer wages increase, discretionary income rises, and greater discretionary spending occurs. A sizeable portion of this discretionary spending goes to jewelry. Major retailers such as Chow Tai Fook and Chow Sang Sang have recognized the potential of these lower-tier cities for years, aggressively moving manufacturing efforts into these areas.

Special Administrative Regions. Hong Kong and Macau are the only Special Administrative Regions (SARs) of the People’s Republic of China. Hong Kong was formerly a British colony, while Macau was a Portuguese colony. They were transferred to China in 1997 and 1999, respectively, under the “one China, two systems” policy. By virtue of their SAR status, Hong Kong and Macau enjoy a high degree of autonomy. While economic studies frequently separate China and Hong Kong, it is important to consider them as one country. The business relationship between the two was established before the change in sovereignty in 1997, especially after the significant economic reforms China instituted in the late 1970s. Many Hong Kong–based businesses set up facilities in mainland China, some right across the border in Shenzhen, to capitalize on less-expensive labor (figure 5).

The advantage of combining low-cost labor and free trade was heightened by the formation of special economic zones (SEZs) in mainland China shortly after the country opened up for trade in 1978. This move fostered free market activity and flexible economic policies, especially for manufacturing and export. The province of Guangdong, including Shenzhen and Panyu, has important SEZs for the diamond, gemstone, and jewelry industries. Many of the products manufactured in these zones are exported to the rest of the world through Hong Kong. Another major economic turning point was China’s 2001 acceptance into the World Trade Organization, which removed trade barriers and created a larger market for Chinese goods.

Five-Year Plan. Since 1953, the government has issued a series of five-year plans outlining economic and social strategies. China is currently in its twelfth five-year plan, from 2011 to 2015. The 2011–2015 plan relies less on exports and more on domestic consumer spending to fuel growth. This most recent initiative emphasizes slower but more sustainable growth, and greater reliance on the domestic market. The current five-year plan (see KPMG China, 2011) outlined several key strategies that will influence the nation’s economy, including:

- Higher-quality growth: GDP growth goals have been reduced to around 7%, with emphasis on curing problems related to earlier rapid growth, such as environmental issues, resource depletion, and excessive energy use.

- Development of lower-tier cities and the western regions: Shifting the emphasis from first-tier cities, primarily in coastal areas, to the less-developed cities and inland western regions has been successful.

- Transition from an export-driven economy to a domestic market economy: The current plan reinforces the need to move from reliance on exports for growth to an emphasis on further expanding the Chinese consumer market.

- Increasing urbanization from 47.6% to 61.6%: Much of this increase will consist of migration from rural areas to the lower-tier cities.

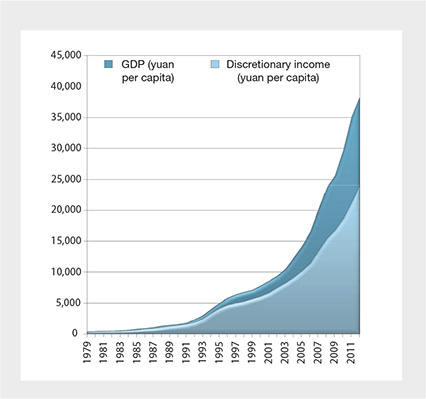

Discretionary Income. Between 2000 and 2011, approximately 230 million people moved to Chinese cities, in what some have considered the greatest urbanization in history (Rare Investment, 2013). The average disposable income of urban residents was expected to rise 13% annually between 2012 and 2047. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the consumption of discretionary goods is expected to grow at a compounded annual rate of 13% between 2010 and 2020 (Barton et al, 2013). The growth rate of discretionary income has been consistently below the GDP growth rate (figure 6).

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the gain in household disposable income has been most prominent among the highest earners, followed by the high-income and upper-middle-class segments, registering compound annual growth rates of 14.5%, 12.8%, and 12.1%, respectively. Members of these classes are the biggest spenders on luxury goods and often have a voracious appetite for the finer things (Fung Business Intelligence Centre, 2013). It is clear that the percentage of discretionary income for higher-income groups has been consistently rising at a faster rate.

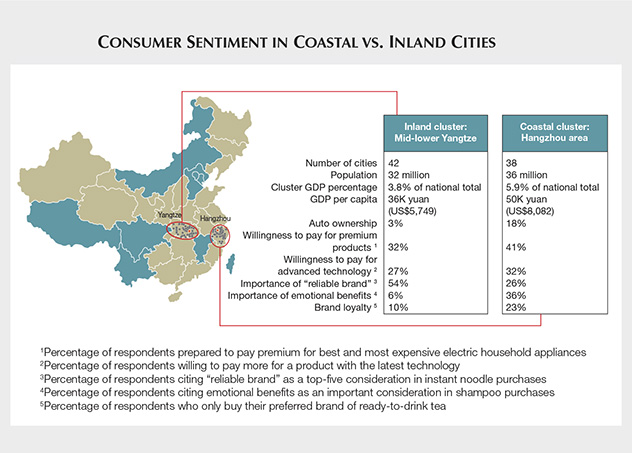

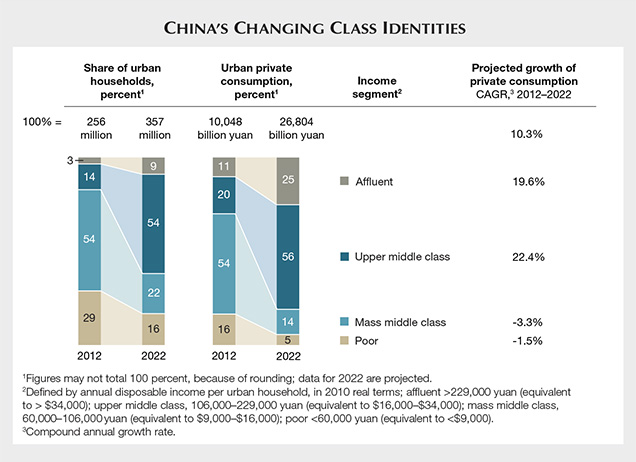

Demographics. The key to future growth in China is domestic consumption. The creation of a vast middle class has fueled the rapidly increasing consumption of goods and services. China’s middle class is projected to expand from approximately 225 million in 2012 to 330 million by 2025 (Schuster, 2012). Percentagewise, the most dramatic increase of the middle class is expected to occur in the second- and third-tier cities farther inland (Barton et al., 2013).

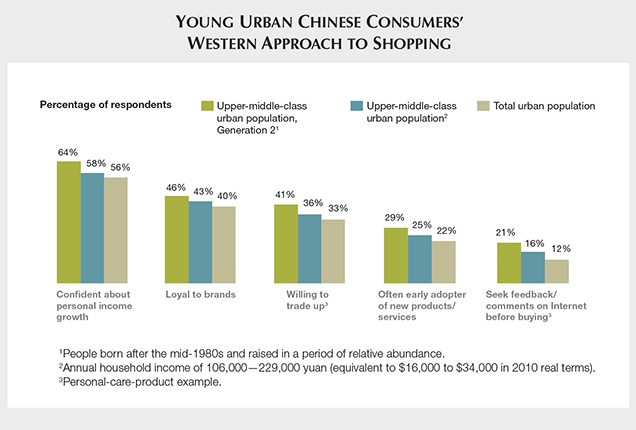

China’s new middle class can also be segregated by age. The average age of individuals with net worth of more than 10 million yuan is 39. Among those with net worth above 100 million yuan, the average age is 41 (Fung Business Intelligence Centre, 2013). China’s Generation 2 (G2) consists of some 200 million youths in their teens and early twenties born since the mid-1980s. This demographic represents about 15% of urban consumers (Barton et al., 2013). By 2022, the G2 segment is expected to be three times larger than the U.S. baby-boomer population, and should make up 35% of the domestic consumer market (Barton et al., 2013). Members of this younger generation have a more Western outlook toward consumption. They are confident of their own financial prospects, loyal to brands, willing to try new products, and comfortable shopping on the Internet (figure 7).

The increase in China’s middle-class population will inevitably lead to greater domestic consumption. In 2002, 40% of China’s still relatively small middle class lived in four cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. By 2022, that percentage is expected to drop to 16% due to the faster middle-class growth of cities in the north and west, especially third-tier cities (Barton et al., 2013). When the predicted increase in the upper middle class is charted alongside the projected increase in private consumption, the importance of middle-class purchasing power becomes obvious (figure 8).

According to the global consulting firm McKinsey & Co., and as shown in figure 9, the most important population sector for domestic consumption is the upper middle class (Barton, 2013). The report defines upper middle class as Chinese citizens with an annual income of 60,000 to 106,000 yuan. The same study estimates that by 2022, the upper middle class will account for 56% of urban household consumption. Like their affluent and ultra-wealthy counterparts, upper-middle-class consumers are contributing to the growth of the luxury products market, which has increased 16–20% annually over the last several years (Barton et al., 2013). By 2015, Chinese customers will account for over one-third of global spending on jewelry and other luxury items, both in their domestic market and outside China.

The upper middle class are the most Westernized of all Chinese consumers. They show a willingness to try new products, and tend to regard expensive products as intrinsically superior. China’s growing middle class also regards discretionary spending on luxury products as an essential element of social status.

Another demographic aspect to Chinese consumption is the increasing contribution by women to household income. By 2009, women provided 50% of household income (Shaun Rein, pers. comm., 2013), while three-quarters of Chinese women say they control the family finances (Georgette Tan, pers. comm., 2013).

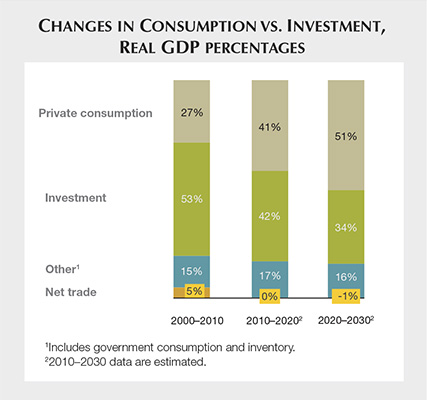

Domestic Consumption. China market analysts predict a shift in the percentage of income used for investment versus consumption (figure 10). In the period from 2000 to 2010, investment comprised 53% of GDP growth, while the rate of private consumption was 27%. These percentages are expected to change dramatically between 2020 and 2030, with 34% of money invested and 51% used for private consumption (Woetzel et al., 2012).

The government expects wages to at least keep pace with, if not surpass, GDP growth. In the first half of 2012, four-fifths of China’s administrative districts raised the minimum wage by 19.7% (Woetzel et al., 2012). While rising labor costs create challenges for global competitiveness in manufacturing, the direction is clear, and the growth of Chinese domestic buying power and consumerism is almost certain.

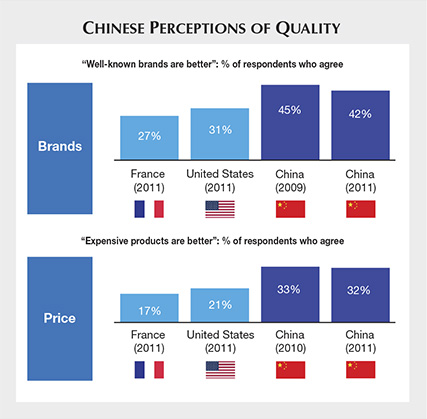

A 2011 survey by McKinsey (Atsmon et al., 2011) revealed several illuminating facts:

- Chinese consumers are often quick to adopt new and unfamiliar products.

- Brand awareness is rising, but not brand loyalty. In China, brands must earn trust. The study found that Chinese consumers are not blindly brand loyal and are willing to change brands if another earns their trust—more so than in the West. Most Chinese consumers choose from several favorite brands.

- Price also exerts a strong influence (figure 11). Chinese shoppers do not necessarily buy lower-priced items, but they do consider the value for the price.

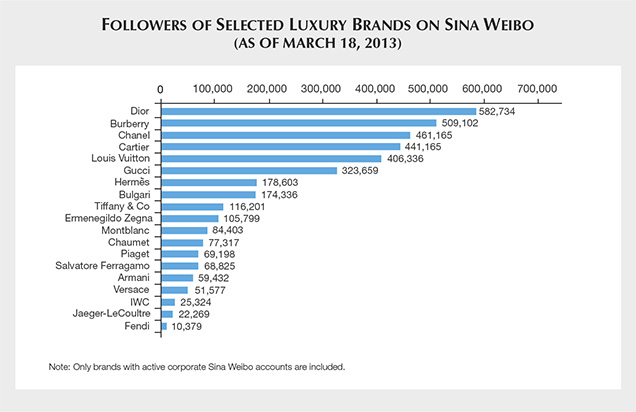

- The popularity of social media is growing at an amazing rate. By mid-2011, 195 million Chinese people used Sina Weibo, the microblogging equivalent of Twitter. That was triple the number from just six months earlier. The instant messaging tool WeChat (also known as Weixin in Chinese) launched in early 2010 and is growing even faster. CNN reported that WeChat registered 100 million users in its first 15 months and had 271.9 million active daily users in September 2013 (Skuse, 2014). Now people can even buy and sell goods on WeChat, similar to eBay.

- Emotional considerations are important in brand choice and purchases among higher-income consumers (though still below U.S. levels) during 2011, and this trend is expected to continue to rise.

- Despite the economic challenges faced in 2011, Chinese consumers are becoming more confident about their economic prospects.

The same McKinsey survey provided useful suggestions for companies wanting to capitalize on growth and opportunity in China in the future.

- Prioritize growth opportunities. While many companies focus on first-tier cities, approximately 60% of consumer goods in urban China are purchased in lower-tier cities.

- Tailor marketing strategies to capture growth opportunities. Regional preferences and differences in disposable income dictate that a China-wide strategy will not work as well as one that is optimized for different regions.

- Focus on perceived value, not price. Chinese consumers seem particularly sensitive to price. Yet low prices are often associated with low quality, and getting good value for the money is the key consideration.

- Build mass appeal and meet the needs of specific consumer groups. As Chinese consumers become more discerning, products must be targeted to certain types of shoppers. Companies that market a variety of product lines to specific consumer groups may be well poised in the coming years.

- Modernize marketing tools. Though expensive, traditional mass-media advertising, such as television commercials, are highly effective in China. Internet commerce and social media gained acceptance more slowly in China than in the West, but the last few years have seen an extraordinary rise in online retail sales and in small businesses using social media. More attention to Internet marketing has the potential to facilitate greater growth.

Import and Export. China ranks 96th out of 189 countries worldwide for ease of doing business (World Bank, 2013); in comparison, the U.S. is 4th and India 134th. China’s standing does not tell the whole story, however. Many businesses, including foreign ones, are opening up in China because of the tremendous growth potential there. Additionally, Hong Kong, which has its own business regulations as a Special Administrative Region, ranks second in the World Bank’s report, and much of China’s trading is done through this free-trade zone. As previously noted, many companies originally based in Hong Kong have moved into mainland China, in part because of the low-cost manufacturing and export, but also to reach the domestic consumer market.

China is the world’s second-largest exporter, just behind the European Union (Central Intelligence Agency, 2013). China is also the third-largest importer of goods, trailing only the European Union and the United States. These statistics demonstrate China’s important role in the global economy.

Luxury Products. Greater China, including Hong Kong and Macau, is the world’s second-largest consumer of luxury products. Chinese consumers purchase half of all luxury products in Asia and one-third of those in Europe (Bain & Company, 2012). The rising rate of luxury purchases in the U.S. is partly due to Chinese tourism. Predictions indicate that the Chinese market will mature but continue to grow both at home and globally, as Chinese tourists travel abroad to shopping destinations such as Paris, New York, and Hawaii.

China’s slowdown in luxury spending growth in 2012 was partly due to increased luxury shopping overseas by Chinese tourists, along with the economic recovery. Chinese trade members interviewed for this article also cited new regulations, brought on by negative publicity, that have discouraged government officials from flaunting lavish luxury gifts.

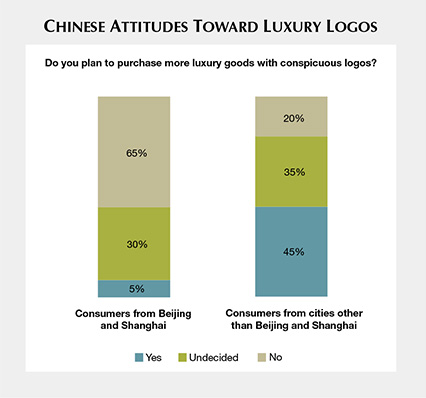

Meanwhile, Chinese consumers are becoming more sophisticated in their shopping habits, moving away from purchasing only brands with well-known logos and toward quality and value in luxury products (Bain & Company, 2012). Even though status symbols remain an important part of the Chinese luxury market, brands that can also demonstrate value are more likely to thrive. Shoppers in first- and second-tier cities are not purchasing goods based on conspicuous branding alone. They are also looking for quality, value, uniqueness, and a low-key statement. Consumers in third- and fourth-tier cities, who tend to be less sophisticated in their shopping, still seek brands with conspicuous logos (figure 12). Yet the cultural heritage of a brand is becoming a more important consideration than just the logo (Fung Business Intelligence Centre, 2013).

Chinese luxury brand shoppers are shifting from predominantly older businessmen to younger shoppers and women (Bain & Company, 2012). Sixty percent of Chinese luxury consumers are between 20 and 39 years of age, compared to only 38% in Western Europe (Fung Business Intelligence Centre, 2013). Only 7% of Chinese luxury consumers are over the age of 60, as opposed to 21% in Western Europe (Hurun, 2013). Notably, 40% of the 102 million Chinese people with personal wealth above 10 million yuan are women. Affluent women’s spending on luxury goods increased from 25% in 2010 to 46% in 2012 (Lui et al., 2012).

Internet Retail. E-commerce in China has grown tremendously in the last few years, including sales of clothing, electronics, and gems and jewelry. Individuals in third- and fourth-tier cities actually spend a higher percentage of disposable income shopping online than first- and second-tier residents (Dobbs et al., 2013). Jewelry companies like Zbird, a pioneer in China’s Internet diamond jewelry sales, have spent years building customer confidence in online purchases. Several Western luxury jewelry retailers, including Cartier, Bulgari, and Tiffany, rank among the most followed luxury brands on social media (figure 13).

China’s phenomenal growth in e-commerce was demonstrated in late 2013, on the unofficial holiday known as Singles’ Day. The event falls on November 11, with the calendar date of 11/11 representing unmarried people. For years, Singles’ Day was a social occasion for China’s large bachelor population. In 2008, the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba began promoting Singles’ Day as an e-commerce event. (Two of Alibaba’s sites, Taobao and Tmall, have a transaction volume larger than that of Amazon and eBay combined.) Most other Chinese e-commerce sites quickly followed suit, offering deals on all types of consumer goods. All told, Singles’ Day 2013 brought in more than US$5.75 billion, making it the biggest one-day e-commerce event of all time, well surpassing Cyber Monday 2012 in the United States (Wang and Pfanner, 2013).

Alibaba alone reported 402 million unique visitors to its sites on Singles’ Day 2013, and prepared 152 million parcels for shipping. The gem and jewelry industry played a role in this success. In one instance, a woman from Zhejiang province purchased a 13.33 ct diamond costing $3.37 million (Wang and Pfanner, 2013).

THE CHINESE GEM AND JEWELRY INDUSTRY

Historical Perspective. Jewelry has a well-established history in China, where gold and silver have been used for decorative purposes for at least 3,000 years. Based on archaeological evidence, the Chinese began using jade even earlier, during the New Stone Age (Zhang, 2006).

With the development of manufacturing techniques, precious metal decoration evolved from the simple gold sheet and leaves discovered in tombs dating from the Shang dynasty (circa 1700–1100 BC) to the delicate jewelries embedded with local and Western elements in the Han and Tang dynasties (265–907). Precious metal art reached its peak during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912), with luxury gold and silver practical wares and jewelries made for the royal families (figure 14) still in existence.

Before jadeite was imported from Burma, early in the Qing dynasty, references to “jade” in Chinese records signified nephrite. Owing to its special color, luster, and structure, nephrite was thought to represent the conservative character of China’s culture and the spirit of its people. Originally used for tools and sacrificial vessels, jade gradually became the stone of choice for practical wares, jewelry, and carvings.

The Qing emperors’ love of jadeite influenced its prominence. Historically, jadeite has been imported from Burma in two ways: through the boundary between the two countries in southwestern China, and through the port at Guangzhou, which became the capital of the jadeite trade. From 1873 to 1878, an average of 200 tons of jadeite was imported yearly through Guangzhou (Li, 2013). Today, the famous jadeite manufacturing and trade centers of Guangzhou, Jieyang, Sihui, and Pingzhou are still very active.

The Modern Jewelry Industry. Throughout China’s history, small-scale manufacturers, along with royal studios and workshops, dominated the market. Once the emperor commissioned a workshop to manufacture an item, the products were hallmarked and could not be traded by private parties. The strict enforcement of this rule on trading delayed the development of the jewelry industry in China.

The modern Chinese jewelry industry began with the rise of Yinlou, private businesses that acted as precious metal manufacturers and dealers, from the end of the Qing Dynasty until the formation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Most of the Yinlou (which translates to “silver mansion” in English) also served as pawn shops. The British victory in the First Opium War (1840–1842) paved the way for the opening of the lucrative Chinese market and society as a whole, which triggered the development of modern industry in China. With access to the breakthroughs of the West’s Industrial Revolution (circa 1760–1840), the Chinese started to form modern factories and businesses.

Unlike the workshops and the royal manufacturers that were the norm before the Opium War, the Yinlou were backed by private investors and operated on a larger scale. There was even a professional guild to represent all these businesses in their dealings with other industries and the government.

By the end of the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century, many of these businesses had established reputations and become leaders in the industry. In Shanghai, nine respected Yinlou formed a jewelry industry association in 1896. Since then, precious metal trading in Shanghai has been self-regulated (Sun and Nie, 2008). Among the original nine companies, Lao Feng Xiang (figure 15) may be the most famous. Formed in 1848, it operated three chain stores in Shanghai until 1949. In 1952, the Communist government bought the stores, and it remains a state-owned business. After numerous ups and downs, Lao Feng Xiang is presently thriving as China’s second-largest jewelry retailer after Chow Tai Fook, with over 2,300 retail outlets all over the country.

Other Yinlou companies were located along China’s east coast. Although nearly all of them disappeared during the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the Cultural Revolution, some survived and are trying to revitalize their business in the current jewelry market. Yinlou helped set the stage for the modern Chinese industry.

Post–Cultural Revolution. After years of war, followed by the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, China finally had the opportunity to modernize its economy. When we talk about this new era of the Chinese jewelry industry, these 30 years can be roughly divided into four stages.

Recovery Period (1976–1989). During the Cultural Revolution, a turbulent period when communism was strictly enforced, jewelry and other luxury products were taken off the market. In 1982, the political constraints imposed on the jewelry industry were finally removed. In 1986, the government released 100 tons of gold to the market for jewelry manufacturing. Following this, the jewelry industry became independent again after nearly 30 years of state control (Zhang, 2008).

New jewelry companies and old brands worked to build their businesses, but sales were severely confined by China’s underdeveloped economy and lack of discretionary income among its citizens. Statistics show that in 1980 there were only 10 gold jewelry manufacturers in the entire country, employing about 10,000 workers (Zhang, 2008). Most stores at this time only carried fine gold jewelry. Consumers had almost no jewelry knowledge, so most purchased whatever was available, simply as a hedge against inflation. With a limited amount of gold circulating in the market, supply often could not satisfy consumer demand. Retailers were primarily state-owned department stores, and privately owned companies were rare (Qiu et al., 2002).

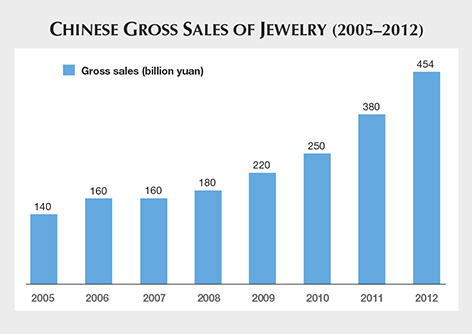

Dynamic Growth (1990–2000). The Chinese jewelry industry experienced a dramatic upswing in the last decade of the 20th century. In the early 1990s, many state-owned jewelry companies formed. With money to invest in human resources and technology, these businesses started to collaborate with foreign companies and large, state-owned department stores. Some foreign jewelry companies entered the Chinese market for the first time, with De Beers forming its first Chinese diamond promotion center in Shanghai. The four most successful Hong Kong jewelry brands (Chow Tai Fook, Chow Seng Seng, Tse Sui Luen, and Luk Fook) entered the mainland market as well (figure 16). By the end of the 1990s, there were about 20,000 jewelry businesses and three million workers involved in the jewelry industry (Gemmological Association of China, 2013). In 1990, gross jewelry sales were about 2 billion yuan (US$300 million). By the year 2000, this number climbed to 89 billion yuan (US$15 billion) (China Economic Net, 2012). The largest growth in the Chinese jewelry industry happened in the 1990s (table 3), and most of today’s companies were formed during this decade.

| TABLE 3. Jewelry sales in China, 1990-2012. | ||

| Data compiled from China Economic Net (2012) and Zhang (2008). | ||

| Year | Gross Sales (billion yuan) | Increase (%) |

| 1990 | 2 | |

| 1993 | 24.1 | 1,105 |

| 2000 | 89 | 269.3 |

| 2001 | 96.5 | 8.4 |

| 2002 | 105.3 | 9.1 |

| 2005 | 140 | 15 |

| 2006 | 160 | 14.29 |

| 2007 | 160 | 0 |

| 2008 | 180 | 12.5 |

| 2009 | 220 | 22.22 |

| 2010 | 250 | 13.64 |

| 2011 | 380 | 40 |

| 2012 | 454 | 19.2 |

With the presence of De Beers, Chinese consumers began to feel more comfortable purchasing diamonds. Some consumers actually paid too much attention to the quality of diamonds. For instance, some customers purchasing a 10-point diamond would insist on G color and VVS clarity (Qiu et al., 2002). Medium- and low-quality corundum were also imported from global sources and trading centers. Jewelry featuring mounted gemstones found a market, but jewelry clientele still knew little about gems. Platinum made its greatest advance in the 1990s. In 1994, China’s platinum consumption comprised only 1% of the world market. In 1998, this figure rose to 23%, with China ranking second in world platinum consumption (Zhang, 2008).

Through the 1990s and into the 21st century, the state-owned department stores were still the main jewelry-selling channel. Some department stores thrived after they start focusing on jewelry sales; Beijing’s Cai Shi Kou store is one famous example. Though no longer a department store, from 1989 to 2012 it was ranked Beijing’s top gold jewelry seller every year. It now markets its own jewelry brand. Guo Hua, also in Beijing, is another success story. After following a path similar to Cai Shi Kou’s, it is now Beijing’s leading platinum jewelry seller.

Steady Growth (2000–2008). In the 21st century, China’s domestic jewelry industry entered a steady growth period. In 2001, the country was the world’s leading consumer of platinum. In 2007, its gold consumption reached 363 tons (figure 17), second only to India’s (Zhang, 2008). As a result of this growth, both the jewelry market and consumers matured. The focus of the industry shifted from quantity to quality. Companies that could not compete went out of business. By 2000, jewelers realized the importance of branding and started promoting products by emphasizing cultural and historical significance rather than simply lowering prices. Consumers started to pay attention to design rather than just focusing on the value of the materials being used.

A New Start (2008–Present). The 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing (figure 18) helped shed light on Chinese society, opening the country even more to the rest of the world. Meanwhile, Chinese tourism abroad has increased, the GDP per capita has risen, and more income is being spent on luxury goods.

While the global economy experienced a severe shock with the recession of 2008–2009, the Chinese jewelry industry slowed only slightly. Trade officials note that with the rise in discretionary income in the early 2000s, jewelry became the third-largest investment purchase, after real estate and automobiles. In 2009, more than 11 million couples got married in China, a number that is expected to rise through 2019 (China Economic Net, 2012). A survey by the Shanghai Diamond Exchange indicated that 8 out of every 10 new couples from first-tier cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai were willing to purchase diamond wedding rings. The Platinum Guild International (PGI) surveyed eight major Chinese cities and found that 84% of prospective brides desired platinum wedding rings (Wen, 2012). And a recent online survey conducted in Shanghai showed that 50% of new couples spent 15,000–20,000 yuan (US$2,500–$3,000) on wedding jewelry (Lin, 2012).

Today’s consumers know far more about the products they purchase than ever before. This is partially due to better disclosure from sellers and easy access to product knowledge through different channels, especially online resources. Many diamond consumers already know exactly what they want before they step inside a jewelry store or place an online order. As Chinese jewelry shoppers have become better educated, they have cultivated more of an appreciation for design, including Western and innovative Chinese styles. In 2013, several Chinese designers conveyed to the authors these changes in their customers’ buying habits. Rather than thinking only in terms of the value of the materials, Chinese jewelry consumers increasingly think in terms of design, value, and the quality of the piece as a whole. Whereas haute couture was very rare in China only five years ago, nearly every mainstream jewelry company now offers luxury products and services. Some designers focus exclusively on custom haute couture jewelry for high-end clientele.

ECONOMIC FACTORS

For any business in China to prosper, it needs the support of government at all levels. Similarly, the government’s fiscal policies can benefit both the individual company and the entire industry. Upon opening the country to trade after 1978, the central government enacted major reforms to catch up with other global economies. Additional reforms, such as anti-corruption measures and environmental protection, are necessary to continue this development.

Tax Reform. Since 1978, China has transformed its tax system several times to adapt to its own rapid economic development. A large-scale transformation of the socialist economy occurred in 1994, with a shift toward free-market policies. Since 2003, China has implemented a series of reforms primarily related to income, property, and export taxes. As of 2012, there were 25 tax categories in China. The central government relies heavily on consumption-based taxes, which are less damaging to individual savings than traditional income taxes (Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, 2010).

Legislative power over tax laws in China is highly centralized. Only the state council can create and reform national tax laws or policies. Tax collecting responsibilities belong to the State Administration of Taxation. Local governments can slightly adjust some tax rates under certain circumstances, but in general, the power of local government to add or remove taxes, or change major tax rates, is very limited.

Unlike the U.S., China relies more on consumption taxes than income taxes. Value-added tax (VAT) is a large portion of the taxes that an enterprise or individual pays; this applies to jewelry companies as well. According to the State Administration of Taxation website, there are two basic rates: 13% and 17%. While exporting certain jewelry industry products, such as colored gemstones, to China can be challenging for foreign companies, gold and diamonds have exchanges in China that have clarified and simplified importations.

Gold Exchange. The Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE), founded by the People’s Bank of China in October 2002, is a nonprofit organization that regulates gold transactions domestically (figure 19). It provides facilities and supervision for gold transactions, sets precious metal prices domestically, and connects the Chinese and international markets. The SGE also works with testing institutions to conduct qualification examinations for gold quality standards.

Several events led up to the formation of the Exchange. In 2000, the government developed a five-year economic plan that included an open gold market (Skoyles, 2013a). A year later, the People’s Bank of China eliminated its monopoly of the nation’s gold market. Shortly thereafter, gold price quotes were released on a weekly basis, allowing for adjustments to the gold spot price to reflect free market prices. This effectively paved the way for the SGE (Skoyles, 2013a). As a result, the price of gold in China is based on the open international market.

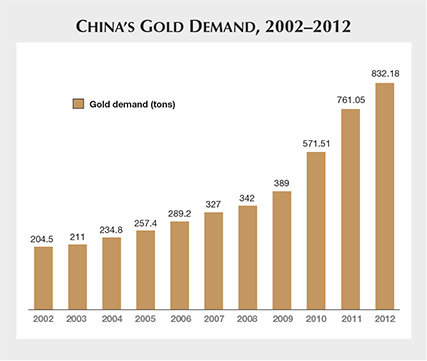

In 2011 alone, over one million gold savings accounts were opened at ICBC, China’s largest bank, as well as 14.4 million gold futures contracts on the Shanghai Gold Futures Exchange. Jewelry remained China’s largest gold demand, with a growth in 2011 of 27.87%, 5.45 times higher than the rate for 2010 (Shanghai Gold Exchange, 2011). Much of this sharp rise was attributed to an increase in personal income and the need for a hedge against inflation; the latter drove investors to buy when prices were rising instead of falling. By 2012, China’s total gold consumption reached 832.18 tons (figure 20), and the SGE had become the world’s largest physical gold exchange.

In the first six months of 2013, the SGE supplied 1,098 tons of gold to China for domestic consumption, totaling more than 25% of global supply (Skoyles, 2013a). SGE has 41 warehouses in 34 Chinese cities to facilitate stocking and delivery of gold. Gold is physically delivered to members three days after a deal is completed.

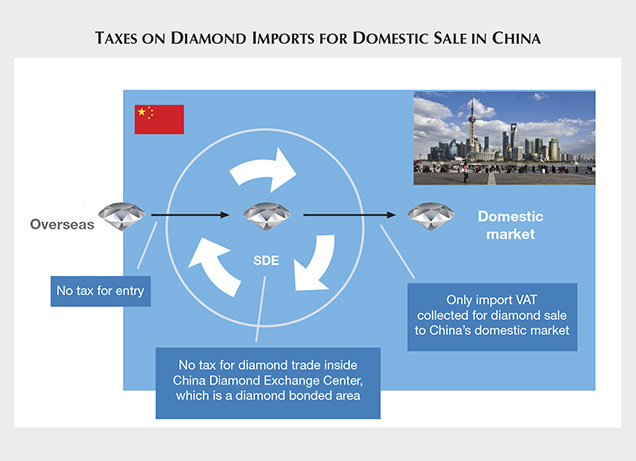

Diamond Exchange. In October 2000, the Shanghai Diamond Exchange (SDE) was established. Housed in the China Diamond Exchange Center (figure 21), the SDE is often referred to by that name. Prior to that, taxation—including tariffs, VAT, and sales tax on diamond imports—was very high, around 35% to 40%. Thanks to the work of the Exchange, diamond taxation policy is now very favorable (table 4). While all goods imported into China are charged a 17% VAT, 13% is refunded for polished diamonds, leaving the net VAT on diamond at 4%. If the rough is polished in China and then sold in the domestic market, VAT is applied, the same as any polished diamond imported into China. If the rough is polished in China and returned to the country of export, then no VAT is applied. These reforms were instrumental in curbing the smuggling of diamonds into the country to avoid taxation.

| TABLE 4. China's diamond taxation policy. | |||

| Data compiled from China Diamond Exchange Center (2013). | |||

| Before June 2002 | June 2002—June 2006 | July 2006—present | |

| Tariff | Rough: 3%; polished: 9% | 0% | |

| VAT | 17% | Rough: 0%; polished: 4% | |

| Consumption Tax | 10% at the import stage | 5% at the retail stage | |

The China Diamond Exchange Center is home to a grading and identification lab, diamond dealers, government agencies, and shipping services. It is the central location for all of China’s diamond imports and exports. The Diamond Exchange handles all import and export of loose diamonds under normal trade, but not diamond jewelry. The Exchange joined the World Federation of Diamond Bourses in 2004 and hosted the 33rd World Diamond Conference in Shanghai in 2008.

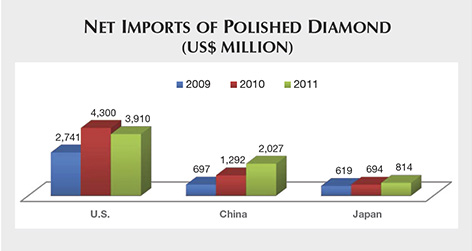

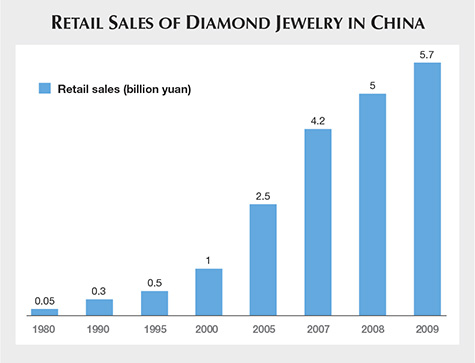

The Chinese diamond industry has benefited greatly from the Diamond Exchange. Before its formation, the official value of diamond imports was about US$1 million annually. By 2011, diamond import value had reached over US$5 billion annually, of which around $2 billion was imported solely into mainland China (figure 22). According to the Diamond Exchange, imports dropped by 10% in 2012 due to worldwide economic conditions, but indications pointed to a higher value for 2013.

The China Diamond Exchange Center is the only legal processing area for diamond import and export. Set up by the central government, its mission is to make trade more convenient by simplifying diamond import and export procedures. According to Chinese law, all imported diamonds must be received at the Exchange to begin the taxation process (figure 23). These imports must be declared and sealed by Chinese customs or else they are considered illegally smuggled. The diamonds are unsealed, inspected, and assessed by an expert at the Exchange before taxation is imposed.

Likewise, imported rough diamonds must be inspected before entering China. Kimberley Process certificates must accompany these diamonds, and a special department in the CDEC is set up for inspecting and registering the certificates. Once the certificates pass inspection, the rough can be sold in the domestic market. After serving as vice chair country of the Kimberley Process for 2013, China became the chair country for 2014, with an officer from China’s National Bureau of Quality Inspection assuming the chairmanship.

The China Diamond Exchange Center is a completely open platform that welcomes diamond dealers from all over the world. It has more than 350 members, of which 67% are from Israel, Belgium, the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Japan, Africa, and other overseas locations. There are 114 member diamond companies from mainland China, 62 from Hong Kong, 50 from India, 32 from Israel, and 23 from Belgium; the remaining 69 are from other countries.

Diamond Administration Center of China. The Diamond Administration Center of China (DAC) was established in April 2000. It is authorized by the Ministry of Commerce to supervise the Diamond Exchange. The DAC and other government organizations jointly control everyday diamond imports and exports across the country, as well as trade within the China Diamond Exchange Center.

Functions of the DAC include administration and statistical analysis of national diamond imports and exports, examination and verification that transactions meet the requirements of the Diamond Exchange, and supervision of the Diamond Exchange’s operations. The DAC also coordinates with other government officials within the Exchange, approves and oversees the activities of foreign-invested diamond countries within China, participates in the creation of diamond import/export policies, and provides services to the Diamond Exchange and domestic and foreign diamond companies.

Colored Stones. Unlike diamonds and gold, which are traded in their own exchange centers with special tax policies, colored stones and colored stone jewelry are taxed at the same rate as other luxury goods. Because China does not have rich colored stone resources, this market depends mainly on imported goods. Tariff, VAT, and consumption tax are collected by the central government, while the local government collects business taxes. The customs tariff of imported colored stones is 8%, and retailers or wholesalers pay an additional 10% business tax. The VAT of mounted colored stone jewelry is an unusually high 17.5%, while consumption tax is 5%. In total, a jewelry retailer or wholesaler pays about 40% on colored stones, driving up prices for these products significantly. For example, a Cartier LOVE bracelet that sold in Hong Kong for 34,855 yuan (US$6,000) in 2013 cost 47,300 yuan (US$8,000) in nearby Shenzhen. This difference of about 35.7% is at least partially due to China’s high tax rate on colored stone jewelry (Fung Business Intelligence Centre, 2013).

Taxes collected by the central government are related to different industries; thus, it takes longer for changes to occur. There are still some special policies that can help to lower these tax rates. For example, the formation of the Diamond Exchange allowed all diamonds to be traded under special tax rates, which effectively lowered the taxes collected by the central government. A similar organization might help with the colored stone industry. Moreover, reciprocal import-export policies between China and other countries help to lower the tariff, as does the formation of some special trade zones in China. The hardest part to change is the VAT, because China’s central government is heavily reliant on this tax. To change it just for one industry is even harder (Qiu, 2013). Local taxes seem to have more flexibility than those collected by the central government, as they are more dependent on the attitude of the local government toward developing its jewelry industry.

LAB STANDARDS

Based on modern gemological knowledge, industry standards were created to standardize the gem and jewelry trade and protect consumers. Over the past 30 years, China formed a series of lab standards based on both Western examples and research by Chinese gemologists.

The three most important are the Jewelry Industry Nomenclature Standard (GB/T 16552-2010), the Gem Identification Standard (GB/T 16553-2010), and the Diamond Grading Standard (GB/T 16554-2010). These standards apply to all labs across the country. They were first published in 1996, and updated versions were issued in 2010 and applied to lab work effective February 2011 (“2010 edition of the three...,” 2011). In addition, there are standards for precious metals.

As the largest jadeite consumer in the world, China has sought a national standard on jadeite grading for years. It is a very difficult process, because jadeite has a wide range of appearances, including transparency, color zoning, and texture. Therefore, every piece is unique and evaluated largely on personal experience using trade jargon. In 2009, the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine and the Standardization Administration published a national jadeite grading standard, GB/T 23885-2009. This standard mainly deals with green jadeite (figure 24), but it can also be applied to transparent, lavender, and red-brown material. The four factors evaluated are color, transparency, texture, and clarity. Gemologists may also comment on the craftsmanship of a particular piece on the certificate. The current standard uses letters to represent different grades while also using the corresponding trade jargon, so that consumers and dealers alike can easily connect the lab report with their goods. The establishment of this standard was supported by both the NGTC lab and high-end jadeite dealers.

China is also the world’s largest cultured pearl producer. In 2002, a grading standard (GB/T 18781-2002) was published regulating the terminology, grading factors, analysis methods, and product labeling for both saltwater and freshwater cultured pearls.

Some other colored stone varieties have a huge market in China, namely ruby, sapphire, rubellite, and more recently tanzanite. Consumers and gemologists expect more national standards to be issued and applied to identification and evaluation so they will be better guided in purchasing and certifying these gems.

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING

In 1980, only 20,000 people throughout China were involved in the jewelry industry. Thirty years later, more than three million are employed in this field. The structure of the jewelry training and education system changed over the same period. The jewelry industry requires workers skilled in mining, manufacturing, sales, and management. At the same time, gemology, design, and engineering experts are also needed for the development of this industry. Compared to many other countries, China has a very specialized jewelry training and education system (figure 25). There are two main components of this system.

Professional Training. Before any modern training organizations formed in China, knowledge was passed from master to apprentice. This system, which existed for thousands of years until the very recent reopening of the country, focused on one-on-one training. It was not efficient in training a large pool of workers. Modern certificate training programs, first established in the West, have been successful in this regard. China imported these foreign programs.

In 1989, the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan formed a collaborative teaching center with the Gemmological Association of Great Britain to launch the first FGA program in China’s history. Fifteen students were enrolled in that program (Yang, 2013). After that, more foreign gemology and diamond certificate training programs were established in mainland China. For example, the Diamond High Council (HRD) opened an education center in Shanghai in 1993, followed by Gem-A in Wuhan a year later. The Gemological Institute of America taught its first Chinese graduate gemology courses in Beijing in 1998. Altogether, these accredited programs trained about 300 students every year (Yang, 2013).

As more gemologists were trained, China started to develop its own certification programs. Different authorities, including universities, national gem and jewelry technology centers, and gemological societies, can all issue professional certifications. The China University of Geosciences in Wuhan, for instance, issues a certificate called the GIC; about 4,000 people were enrolled in this program in 2012 (Yang, 2013). The training content in these courses includes gemology, manufacturing, design, sales, and management. Competition between education providers, both foreign and domestic, has led to the development of more specialized training programs. Many local labs offer high-end classes for management-level personnel from jewelry companies, banks, and insurance companies to help them better understand the trade and related investment options. Labs and associations at the national level also collaborate with sales experts from leading jewelry brands to offer sales and management classes for store personnel. Some jewelry advisors even offer one-to-one classes for high-end investors and collectors.

Gemology Certificates and Degree Programs. Another distinguishing feature of the training system in China is its higher-education programs in gemology. Since the mid-1980s, some universities have offered gemology degrees, which are equivalent to an associate’s degree in the United States. The Gemmological Institute at the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan, the first of its kind officially registered by the central government, was formed in 1992. In 1998, the Ministry of Education added gemology as a major in the nation’s universities (Yang, 2013), allowing students to pursue degrees up to and including doctorates. This academic major expanded to include jewelry design, jewelry manufacturing, and jewelry business management. In 2009, the Gemmological Institute in Wuhan became the first university to offer a master’s-level program in jewelry design (Yang, 2013).

To secure the talent needed to compete in the jewelry industry, many companies provide their employees with special training and higher salaries. The president of the Pingzhou Mazu jadeite company pointed out that many of his jadeite carvers earn salaries of more than one million yuan per year (US$150,000). The factory leader from one major diamond-cutting factory in Guangdong province also noted that salaries there have increased by about 15% annually for several years.

JEWELRY MANUFACTURING

China, the world’s foremost manufacturing center, is arguably the leading jewelry maker. Most of these operations are based in Guangdong province. Over 2,000 companies are located in Shenzhen, with an annual output of US$8 billion. This is estimated at over 70% of China’s actual jewelry production (“Shenzhen steps up role...,” 2012). China is moving from a primarily low-cost manufacturing model to one with a highly skilled workforce and state-of-the-art technology such as laser sawing for diamonds, computer-aided diamond cut planning, highly precise robotic cutting for colored stones, and vacuum-casting in platinum. The industry is investing heavily in technology as well as staff skill level.

The Chinese jewelry manufacturing industry faces the challenges of rising costs, consumer sophistication, value chain complexity, and global economic uncertainty. One of the biggest obstacles is the supply of rough material. The Chinese manufacturing industry is already known for its appetite for rough colored stones (figure 26). During interviews at the 2013 Tucson gem shows, several U.S. dealers confirmed the difficulty of acquiring rough when trying to compete against China (Gemological Institute of America, 2013). Many dealers said they could not compete against the prices offered by Chinese cutting firms and jewelry manufacturers.

To feed the growing demand for colored stones, China is making investments in African nations to secure a supply of raw materials. One of the largest investments has been in developing African infrastructure, a strategy outlined in five-year plans since 2001 (Ashok, 2013). Some of these African locales produce diamonds. Zimbabwe, potentially a major diamond producer, is one of the countries where Chinese goods, services, and capital have been traded for rough diamonds since 2011 (Ashok, 2013), and so far this strategy has been successful. Between 2006 and 2011, when there was a 3% fall in global rough supply, China posted a 20% increase in rough diamond imports by weight and a 55% increase by value (Ashok, 2013). Diamond sourcing will remain a challenge as the global competition for rough intensifies.

China, once a primarily low-cost manufacturing center, faces the challenges of rising costs, greater consumer sophistication and demands, value chain complexity, and global economic uncertainty. The country now boasts a highly skilled workforce, state-of-the-art technology, and high-quality products, including gemstones and jewelry These factors will help address most manufacturing concerns.

THE DOMESTIC GEM AND JEWELRY MARKET

While China has been a leading force for manufacturing and exports in the global jewelry industry, the most anticipated development has been the growth of its domestic market. The rise in wages, though a competitive challenge for China’s manufacturing sector, has created great opportunities for its retail jewelry industry.

Domestic Jewelry Market. China is now the second-largest jewelry market in the world. Although there have been boom years and slower years, the overall growth has been remarkable (figure 27).

When gold prices plummeted in April 2013, Chinese consumers seized the opportunity to buy gold, including fine gold jewelry, at bargain prices. Retail sales for jewelry that month totaled 30.3 billion yuan (US$5 billion), a 72.2% year-on-year growth (HKTDC Research, 2013).

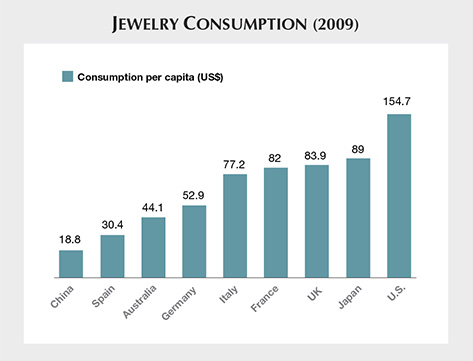

While the growth of domestic jewelry consumption in China has been impressive over the last few years, there is still room for advancement. Per capita jewelry consumption is still relatively low compared to many other global markets (figure 28). Since 2009, jewelry consumption in both China and the United States has risen significantly, with China’s consumption per capita more than doubling. Still, Michael Huang, managing director of the Diamond Index Group, noted that China’s jewelry consumption still lagged far behind the major developed countries (Krawitz, 2013). China now has an estimated jewelry consumption per capita of US$44, compared to Japan at $91 and the U.S. at $242 (Krawitz, 2013).

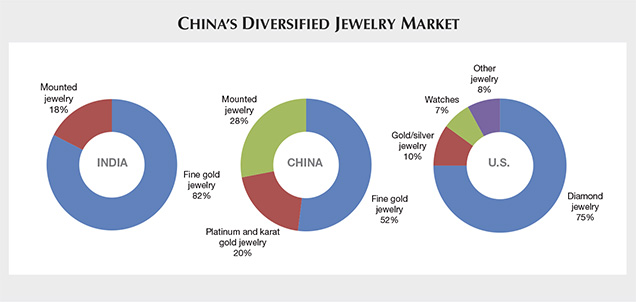

Gold Jewelry. As figure 29 demonstrates, fine gold jewelry is still a major seller in China. By 2012, China consumed 518.8 tons of gold jewelry and was the world’s fastest-growing market for gold jewelry; more than 75% of Chinese women in urban areas own a significant piece of gold jewelry (World Gold Council, 2013). Two-thirds of Chinese women regard gold jewelry as more of an investment than an adornment. Yet in 2013, some 6.6 million Chinese brides were expected to receive gold as part of their wedding ceremony (World Gold Council, 2013). Clearly, gold also holds an emotional and sentimental value in China.

In the United States, diamond jewelry makes up a much higher percentage of overall jewelry consumption. But with the growth of the new consumer classes in China and the development of lower-tier cities, the domestic market for diamond and gemstone jewelry should continue to grow, with the market eventually becoming more diversified. This is already the case when one compares China’s proportion of jewelry consumption categories to those of India and the United States (figure 30).

Chinese consumers traditionally have a strong preference for 24K gold jewelry because of its intrinsic value and the cultural affinity for purity. 24K gold accounts for more than 80% of the gold jewelry sold there (World Gold Council, 2013).

Gold has made inroads into the gem-set jewelry market, in both bridal and Western designer jewelry. In 2008, the World Gold Council collaborated with Chinese designers and manufacturers to create a line of 18K jewelry branded as K-Gold. This line was intended to inspire new designs and attract younger consumers seeking to combine tradition with innovation. The World Gold Council also launched advertising campaigns for two gold jewelry collections. These lines, the “Sign of Love” and the “Code of Love,” capitalized on the tradition of gold jewelry as the first important gift in a romantic relationship.

By 2013, China was on track to overtake India as the world’s largest consumer of gold (World Gold Council, 2013). That year, David Lamb, global managing director of jewelry and marketing for the World Gold Council, noted in an interview on the organization’s website that more jewelry stores are opening in second- and third-tier cities. This reflects the greater consumer demand as these cities undergo economic development. In the same interview, he also mentioned a renewed interest in pure gold jewelry, as opposed to 18K and other karat gold jewelry.

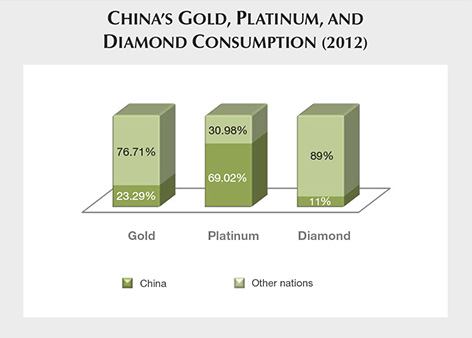

Platinum Jewelry. China is the world’s leading consumer of platinum, accounting for about 68% of the world’s demand in 2012 according to Platinum Guild International. In a 2012 speech, Platinum Guild CEO James Courage noted that since 1997, PGI has invested US$150 million into the Chinese market to promote the precious metal, an investment that has yielded a US$4.3 billion net return to the platinum industry. Courage added that jewelry represented about 31% of worldwide platinum consumption. Platinum jewelry purchases in China rose in by 16% over 2011, with 1.95 million ounces of platinum consumed as jewelry (Johnson Matthey, 2013).

In the Chinese market, women typically decide when to buy jewelry and what to purchase, whether it is a self-purchase or a romantic gift. Most of the platinum jewelry sold in China does not feature gems, but there has been an increasing trend to purchase it with gemstones, especially diamonds, for the bridal market. PGI’s market research shows that platinum’s natural white color and durability are seen as a fitting symbol for purity and a lifelong commitment in the Chinese bridal culture. (Stone Xu, pers. comm., 2013).

Mr. Courage described visiting Chinese platinum jewelry factories that employed more than a thousand people and produced tons of jewelry (Johnson Matthey, 2013). Major jewelry manufacturers in China often have large showrooms where retailers come and select the merchandise they want to buy for their stores. In fact, the showrooms in China are larger than the authors have seen in any other country, with cases full of inventory and buyers purchasing by the kilo. This general observation also applies to platinum jewelry.

Like other retail markets, China has seen a shift from stand-alone retail stores to jewelry sections in department stores and specialty malls for jewelry. This is especially true in the second- and third-tier cities. Department stores often showcase a variety of jewelry in high-traffic areas on the ground floor. According to PGI, platinum jewelry usually represents 10% to 20% of the entire jewelry inventory, a higher percentage than in other markets.

Consumers in second- and third-tier cities often buy 24K gold jewelry but aspire to be like their first-tier counterparts. PGI reports that in a cosmopolitan city like Shanghai, 60% of the wedding rings purchased are platinum. As disposable income rises in lower-tier cities, PGI foresees a higher marriage rate and a higher percentage of platinum wedding rings. The same study notes that in larger cities, Chinese consumers are starting to adopt the Western trend of three-band wedding rings. This may also become the trend in second- and third-tier cities.

Silver Jewelry. China is the world’s largest silver jewelry manufacturer. While industrial applications accounted for more than half of Chinese silver fabrication at 56%, jewelry fabrication accounted for 34% in 2011 (Silver Institute, 2012). Domestic consumption of silver jewelry rose dramatically as styles moved beyond the bulky traditional designs for weddings and birth celebrations. Younger Chinese consumers in first- and second-tier cities began to embrace silver jewelry after 2006, and most of the promotion has focused in these areas. Recently, consumers in rural areas have adopted silver jewelry as a lower-cost alternative to white gold and platinum. Rhodium-plated silver jewelry has also become popular, as it offers the look of platinum. Domestic manufacturers have been duplicating their gold jewelry lines in silver to provide lower-cost alternatives to a broad Chinese consumer market, especially entry-level customers.

Diamond Jewelry. China is now the second-largest diamond market, after the United States. Over the course of five years, diamond jewelry has grown from about one-quarter of China’s total retail jewelry market to approximately one-third (“All that glitters...,” 2013). China is also expected to lead diamond jewelry market growth, along with India, in the global market (Bain & Company, 2013). Much of this growth has come from accepting the Western tradition of giving diamond engagement rings and wedding rings. In China, there are an estimated 13 million brides per year (“All that glitters...,” 2013). There has been a steady shift from gold wedding bands to diamond rings. According to Stephane Lafay, Tiffany’s head of Asia Pacific and Japan, the number of urban people in China buying diamond engagement rings has risen from less than 1% to over 50% in the last 20 years (“All that glitters...,” 2013). In turn, large Chinese jewelry companies that were built on 24K gold jewelry, such as Chow Tai Fook, have moved into the diamond jewelry market.

While growth has fluctuated since 2011, Kent Wong, managing director of Chow Tai Fook, noted that the Chinese jewelry market was cyclical, especially during changes in the central government and its policies (Krawitz, 2013). With diamond’s tradition as a symbol of love, eternity, and purity—and the relatively low per capita consumption today—growth seems almost inevitable. Add to that the Western-inspired trend of diamond jewelry as a gift for special occasions, along with the rise of diamond fashion jewelry, and it is clear to see why many in the industry are looking to China for growth.

In 2012, Rio Tinto released results from a study by the global market research company Ipsos that showed the Chinese consumer was becoming more open to affordable, fashion-flexible diamond jewelry (“Rio Tinto research confirms strong potential…,” 2012). While diamond consumption in China represents a far lower percentage of global consumption than gold or platinum, the market shows enormous growth potential (figure 31).

Colored Gemstones. In recent years, especially since 2010, China’s consumption of jewelry has expanded to colored gemstones. While retail colored stone sales have been highest in first-tier cities, second-tier purchasers are close behind (table 5). As consumers in third- and fourth-tier cities earn more discretionary income, their retail consumption of colored stones should also increase substantially.

| TABLE 5. Colored stone retail sales in China by year (billion yuan). | |||||

| Data compiled from Lu (2013). | |||||

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Gross retail sales | 4.3 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 13.4 |

|

First-tier cities

|

1.8 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.6 |

|

Second-tier cities

|

1.6 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5.1 |

|

Third-tier cities

|

0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

|

Other

|

0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

Many dealers at the 2013 Tucson gem shows reported a rebound in U.S. customer sales and a strong presence of Chinese buyers (Gemological Institute of America, 2013). They also noted dramatic price increases that were primarily due to Chinese consumption. In fact, several dealers pointed to problems replenishing their inventory. In the words of one U.S. colored stone dealer, “I went to a mine to buy rough, and a Chinese buyer had already been there and bought their production. When I returned six months later, the Chinese had purchased the mine.”

Dealers at the 2013 Tucson shows reported that Chinese buyers were interested in a wider variety of colored stones than in years past. Red is traditionally a popular color in China, and ruby and rubellite tourmaline (figure 32) have been popular there for many years. In fact, many trade members have attributed skyrocketing prices for those two gems to the Chinese market. When Christie’s held its first jewelry auction in mainland China in Shanghai on September 26, 2013, a ruby and diamond necklace commanded the highest bid, at $3.4 million (“Ruby necklace tops Christie’s first China auction,” 2013). Based on the authors’ observations and feedback from the industry, other red and pink gemstones such as spinel, garnet, rose quartz, and red jasper also appear to be gaining a following in China.

Gemstones in other colors are also in demand. Multicolored tourmaline jewelry is becoming more popular in response to the rising price of rubellite (“Tourmaline grips Chinese collectors,” 2013). Both blue and green tourmaline, alongside other blue gems like sapphire, aquamarine, blue topaz, and even lesser- known gems like cat’s-eye siliminate, are gaining a foothold in the Chinese market (“Blue and green gems on the rise…,” 2012). Blue to violet tanzanite has become especially popular. Recently, the large retailer Chow Tai Seng, with 2,200 stores domestically, was named a “retail polished sightholder” with TanzaniteOne (Max, 2013), which demonstrates the Chinese market’s openness to nontraditional colored stones. China’s consumers have become aware of all the gemstone choices, and more of these choices at many price points are now available to them.

Enzo, the retail division of LJ International, recently acquired a copper-bearing tourmaline mine in Mozambique (figure 33). With 250 retail stores in mainland China, Enzo hopes to popularize this rare and unusually vivid gemstone domestically (Lorenzo Yi, pers. comm., 2013). These tourmalines are being promoted through advertising, the trade media, and celebrity endorsement.

One of the biggest challenges facing the Chinese colored gemstone industry, for both exports and domestic consumption, is sourcing material (Wilson Yuan, pers. comm. 2013). The fierce competition for many varieties of colored stones, particularly finer-quality material, has also been felt in other manufacturing centers such as India, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. As Chinese consumer demand has grown, the price of colored rough has soared. These price increases have had some positive global effects. For instance, some mines that were not previously economically viable (such as rubellite mines in Brazil) are now able to operate.

Jadeite. While jadeite does not have as long a history in China as nephrite, it is still one of the country’s most popular gem materials. The Guangdong Province Jade Association notes that since the late 1990s, thousands of tons of rough jadeite have been imported through the port of Guangzhou (Tingxin Li, pers. comm., 2013). The jadeite is carved or manufactured locally, making Guangdong the national hub of jadeite manufacturing and sales. The Pingzhou region of Guangdong, China’s largest jadeite rough market, is referred to as the “hometown” of the jadeite bracelet (figure 34). More than 20 auctions are held here each year, attracting dealers and retailers from all over the country. The Sihui area draws carvers from Putian and Nanyang, who apply skills and concepts from wood and stone carving to jadeite.

Another important entry point lies along the border between China and Myanmar in Yunnan province, China’s earliest jadeite import locale. There were about 6,000 jadeite companies in Yunnan in 2007; five years later, this number had increased to 21,000 (Tingxin Li, pers. comm., 2013). The main markets there are concentrated in Tengchong, Yingjiang, and Ruili.

From 2000 to 2009, the price of jadeite rose by an average of 20% annually. For 2011 and 2012, this rate increased more than 30% annually (China Industrial Information Network, 2013). Myanmar, which produces much of China’s jadeite, wants to strictly control its export and develop its own mine-to-market business, even as the Chinese demand for high-end jadeite continues to grow. Some jadeite dealers were forced to tap into their reserves to deal with the lack of rough. At the June 2013 Myanmar jadeite auction, rough prices skyrocketed. In total, fewer than 10,000 pieces were available for purchase (compared to 20,000–30,000 pieces in previous auctions), while prices were three to ten times higher (Chen, 2013). Trade experts from both Yunnan and Guangdong said the retail price of high-quality jadeite increased at about the same rate as the rough price; medium- to low-quality jadeite was not as affected. The price hike was not well received by Chinese consumers, who did not want to spend much money on lower-quality material (Tingxin Li, pers. comm., 2013). High-end jadeite products are still in demand among Chinese collectors and investors—in China and around the world—even at significantly marked-up prices.

IMPORT AND EXPORT

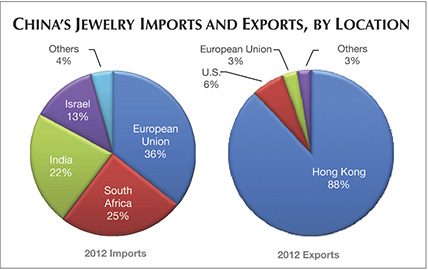

Looking at imports of jewelry by country (figure 35, left) and value, the importance of the EU and its branded luxury jewelry lines to China’s market is evident. The import value is even more impressive when one considers all the purchases of European jewelry made by Chinese consumers traveling abroad. At the other end of the import range are low-end commercial lines from India.

The significance of the “one China, two systems” policy governing mainland China and Hong Kong becomes clear when looking at China’s jewelry exports by country. Although Hong Kong is part of China, it is also a free trade area and in an excellent position to serve as China’s export center. In 2012, 88% of China’s jewelry was exported to Hong Kong (figure 35, right), most of it for distribution in the global market.

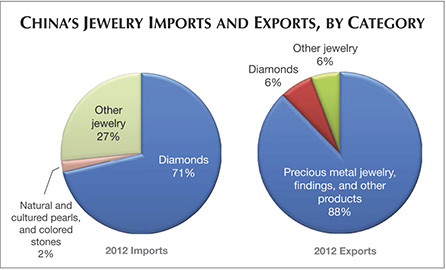

Diamond jewelry represents the largest percentage by value of jewelry imports into China, at 71% in 2012 (figure 36, left). This is partly due to the efficient import channels via the Diamond Exchange, the VAT refund lowering the cost of diamond jewelry to Chinese consumers, and the inherent value of the product. As seen in figure 36 (right), China is a major supplier of jewelry to the global market; the largest category of export is findings and precious metal jewelry. Diamond and gemstone jewelry have significant room for expansion in the overall percentage of exports, while imports and exports of colored gemstones and cultured pearls have seen consistent gains (table 6).

| TABLE 6. Chinese imports and exports of gemstones and natural and cultured pearls (in billion US$). | |||||||

| Source: United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (2013). | |||||||

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Imports | 3.5 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 10.8 | 14.9 |

| Exports | 5.5 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 27.5 |

SUMMARY

China is currently the second-largest jewelry consumer in the world. Its economy has shown phenomenal growth and resilience over the last 30 years, averaging around 10% annually. Although its growth is expected to slow over the next several years, China may still overtake the U.S. within the next decade. The latest five-year national plan, issued in 2011, emphasizes sustainable growth coupled with policies to develop domestic consumption. Large numbers of Chinese citizens are expected to migrate to cities over the next decade, and less-developed inland cities are specifically targeted for growth. As discretionary income grows, particularly in the third- and fourth-tier cities, so should domestic consumption of goods, especially luxury goods such as jewelry. Meanwhile, China’s Generation 2, born after the mid-1980s, is considered global-minded and open to Western-style product consumption. Their confident outlook on the future is a positive signal for discretionary spending.

Brands and quality considerations rank very high among Chinese consumers, although brand expectations vary. For instance, residents of lower-tier cities tend to purchase goods with conspicuous logos, while shoppers in the cosmopolitan coastal cities favor understated sophistication. Chinese luxury consumers tend to be younger than their U.S. and European counterparts and are already predisposed to consider luxury goods a necessity. With the success of e-commerce campaigns, such as Singles’ Day on November 11, the continued growth of Chinese consumption seems almost a foregone conclusion.

When China reopened to the world market, jewelry businesses in Hong Kong took advantage of lower-cost labor in Guangdong province and the newly established free trade zones. The “one China, two systems” policy, which has maintained a free market in Hong Kong since reunification in 1997, stimulated rapid growth in Chinese exports. Some of these same jewelry businesses from Hong Kong moved into the domestic Chinese market as it took off. The creation of the Shanghai Diamond Exchange and the Shanghai Gold Exchange led to the reform of import and export protocols, including revision of tax policies, and this fueled the growth of the domestic jewelry industry. While rising labor costs are a concern to China’s jewelry manufacturing industry, the adoption of technology and the move to the high-end market have kept it competitive globally.

China’s consumption per capita of jewelry is low compared to the United States, but it is rising at a dramatic rate. The success of platinum in a relatively short time shows an openness to new products. Diamond jewelry has been very popular in China, especially in the bridal market, and diamond fashion jewelry is also considered a new sector for growth. A variety of colored stones are being marketed and gaining interest in the domestic market. The global markets for colored gemstones such as ruby, rubellite, and tourmaline have already been profoundly impacted by Chinese consumers (figure 37). Other stones such as tanzanite are gaining considerable traction, while the more traditional jadeite remains extremely popular.

While it remains a global manufacturing leader, China is also developing and diversifying its domestic jewelry market. Although the country faces challenges such as wealth disparity, environmental issues, and bureaucratic obstacles, China’s dynamic gem and jewelry industry seems destined for an even brighter future.