Fall 2015 G&G: Trapiche Emeralds, Synthetic Diamonds and a Large Diamond Source

November 4, 2015

A report on Colombia’s unique trapiche emeralds is the cover feature of the fall 2015 issue of Gems & Gemology (G&G), which also offers an analysis of large synthetic diamonds produced in Russia and a detailed look inside the Letšeng Diamond Mine in Lesotho (the leading source for mega-sized diamonds).

Colombian Trapiche Emeralds: Recent Advances in Understanding Their Formation

Colombia’s trapiche emeralds show a distinct pattern that resembles a wheel with six spokes. They are found only in the black shales of the country’s western emerald zone near the legendary mines of Muzo, Quiopama and Coscuez.

The researchers, Dr. Isabella Pignatelli, Gaston Giuliani, Daniel Ohnenstetter, Giovanna Agrosì, Sandrine Mathieu, Christophe Morlot and Yannick Branquet, performed spectroscopic and chemical analyses on the samples to determine how they formed within their geological setting. They determined that super-pressurized fluid within the black shale helped grow the emerald seed crystals and provided a unique growth environment for them to form into trapiches.

Large Colorless HPHT-Grown Synthetic Gem Diamonds from New Diamond Technology, Russia

In the past five years, the vast majority of synthetic diamonds appearing in the gem market have been manufactured by the Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) process, which has been viewed as more efficient than the older High Pressure, High Temperature (HPHT) method, especially for colorless stones.

A Russian manufacturer, New Diamond Technologies, however, has introduced a line of large HPHT grown colorless synthetics and offered 44 samples to GIA for analysis.

GIA researchers Ulrika F.S. D’Haenens-Johansson, Andrey Katrusha, Kyaw Soe Moe, Paul Johnson, and Wuyi Wang analyzed the samples using a combination of spectroscopic and gemological techniques to characterize the quality of the material and determine the means of distinguishing them from natural, treated and alternative laboratory-grown diamonds.

These samples had weights ranging from 0.20 to 5.11 carats, color grades from D to K, and clarity grades from IF to I2. Importantly, 89% were classified as colorless (D-F), demonstrating that HPHT growth methods can be used to routinely achieve these color grades.

Letšeng’s Unique Diamond Proposition

The Letšeng-la-Terae diamond mine in Lesotho is the world’s most consistent source of type IIa diamonds (those with exceptionally low nitrogen content), which account for about one-fourth of its production. The mine claims six of the 20 largest diamonds ever discovered: 478, 493, 527, 550, 601 and 603 carats. The largest of these, the Lesotho Promise, was found in 2006 and sold to London jeweler Laurence Graff for $12.4 million.

The report by Russell Shor, Robert Weldon, A.J.A. (Bram) Janse, Christopher M. Breeding and Steven B. Shirey, also notes that Letšeng’s diamonds are unusual in that a majority are dodecahedral in form, which are very rare in other sources. Despite its bounty, Letšeng has had a difficult history because its ore grade is extremely low – about 2 carats per 100 tonnes and was not economic until recovery technology and diamond prices improved to allow profitable operation.

Origin Determination of Dolomite-Related White Nephrite through Iterative-Binary Linear Discriminant Analysis

Determining the origin of nephrite jade always has been difficult using standard gemological properties and observations. The authors, Zemin Luo, Mingxing Yang and Andy H. Shen, sampled nephrite jade from eight different dolomite-related deposits in eastern Asia.

The authors used a new statistical analysis method based on linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and trace-element data from laser ablation−inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), to achieve significantly improved origin determination (an average of 94.4% accuracy) for these nephrite samples. This technique could be applied to other gemstones to determine their geographic origins.

Lab Notes

This section of G&G features a discussion on unusual graining structure in a very light pink diamond with a uniform color plane intersecting with a cone of strain that fit perfectly into a colorless hole; an HPHT treated yellow diamond whose treatment was discovered by spectroscopic analysis; and an emerald with strong color zoning along the pavilion facets that demonstrates the importance of proper orientation and cutting. Other lab notes include a look at irradiated green-blue CVD synthetic diamonds that are the product of new growth technology; a natural green jadeite carving with areas that had been dyed green; and an examination of three large, natural abalone pearls.

Micro-World

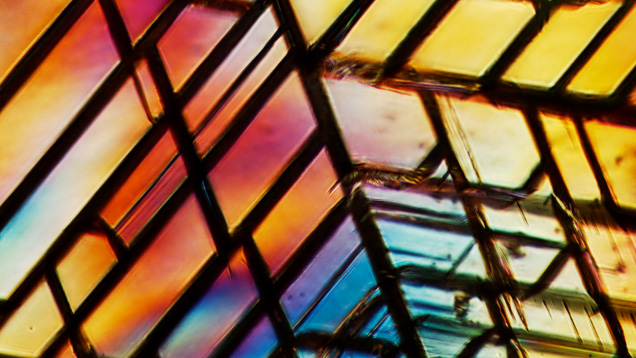

The Micro World section shows a Fancy Intense purplish pink diamond with an intricate geometric pattern of planar cracks and strain-induced bodycolor; an otherwise colorless rough diamond that has an eye-visible bluish-green stain near the surface caused by radiation; blue octahedral crystal inclusions within helidor cabochons that are determined to be gahnite, a rare zinc-rich member of the spinel group; and a trapiche pezzottite reportedly found near the Thai-Myanmar border.

Other features in this section include glassy melt inclusions in alluvial Montana sapphires, molybdenite inclusions in colorless topaz, and a lighting technique from gemological microscopy, Modified Rheinberg Illumination, that provides false-color contrast to enhance inclusion scenes.

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.

.jpg)