Gems & Gemology’s 7 Most Unusual Encounters from 2019

December 13, 2019

Each year, GIA’s laboratories receive an enormous variety of diamonds and colored stones for grading and identification and origin reports. Specimens that are rare or eye-catching or reveal unusual characteristics appear in the quarterly Lab Notes column of Gems & Gemology. Here are G&G’s seven most interesting and unusual from 2019.

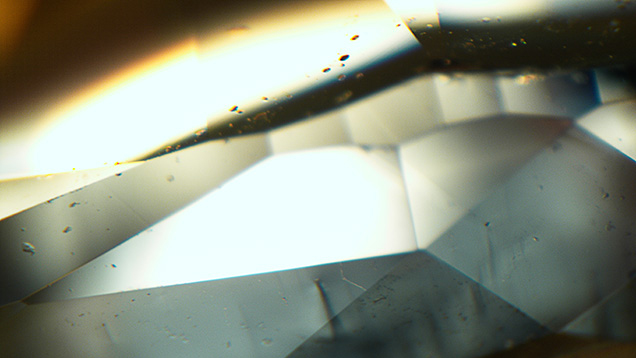

1. Diamond on Diamond: CVD Layer Grown on Natural Diamond

A 0.64 ct Fancy grayish greenish blue cushion modified brilliant showed two distinct fluorescence patterns, as well as characteristics of both type Ia and type IIb diamond. The specimen was found to be a composite of a CVD synthetic diamond layer on top of a natural diamond. This was only the second such composite seen at GIA, but it could represent a new type of product entering the market.

2. Big Sky, Big Ruby: Large Montana Ruby

Montana’s secondary deposits produce sapphire in a wide range of mostly pastel colors. Pink sapphires from Montana are rare, and corundum with enough depth of color to be called ruby are rarer still. A 1.70 ct purplish red octagonal modified brilliant was examined. Its color and large size made it an exceptional specimen—only the second report for a Montana ruby issued by the lab to date.

3. V for Vanadium: High-Vanadium Color-Change Burmese Sapphire

A 5.68 ct transparent cushion mixed-cut sapphire displayed a strong color change from grayish violet in fluorescent light to purple-pink in incandescent light. Chemical analysis showed an unusually high level of vanadium, the first time the Carlsbad lab had encountered a color-change sapphire with this chemistry profile.

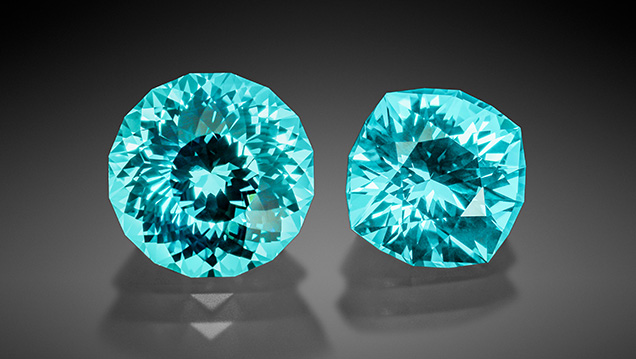

4. Neon Faux: Paraíba-Like Synthetic Sapphire

Two gemstones, 7.78 and 4.90 ct, had a neon green-blue to blue-green color similar to that of Paraíba tourmaline. Curved color banding and Plato lines identified them as flame-fusion synthetic sapphire. This was the first time GIA’s Carlsbad lab had examined flame-fusion synthetic sapphire with a Paraíba-like color.

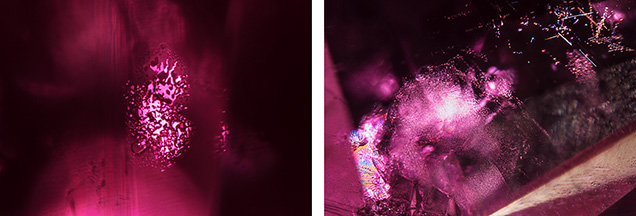

5. Not Easy Going Green: Rough Diamond with Fake Green Coating

Natural green diamonds are extremely rare. Their color is typically caused by exposure to radioactive minerals and fluids, which is accompanied by green or brown patches called “radiation stains.” A 6.49 ct green crystal was found to have been coated with chromium oxide powder, followed by annealing of the powder to produce surface plates resembling radiation stains. While the coating was easily detected with magnification, this was a significant attempt to mimic the features of natural green diamonds.

6. Stellar Stellate: Diamond with Remarkable Stellate Cloud

A 3.70 ct faceted Fancy brownish greenish yellow diamond contained an eye-visible stellate cloud inclusion consisting of six legs that each radiated to a point on the polished octahedron. This “asteriated” diamond was striking due to the well-defined nature of the star and the strong yellowish green color it exhibited under long-wave UV. The faceted octahedron cutting style was unconventional, but served to showcase the inclusion scene contained within the diamond.

7. Mega Stars: Large Laboratory-Grown Star Ruby and Sapphire

Two unusually large loose stones with asterism—a 4,759 ct red sphere with a diameter of approximately 76.96 mm, and a 467.2 ct blue cabochon measuring approximately 52.04 × 42.29 × 20.89—were identified as synthetic ruby and synthetic sapphire. While synthetic star corundum is not particularly rare, these were among the largest laboratory-grown star rubies and star sapphires submitted to GIA.

Be sure to check out every issue of Gems & Gemology for more interesting and unusual Lab Notes.

Stuart Overlin is the managing editor of Gems & Gemology. Brooke Goedert is a writer/editor for gemology content strategy at GIA. Kellie Giordano is the digital communications manager at GIA.