A Visit to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

October 29, 2014

This report documents the museum’s remarkable reference collection as well as its active research programs. You’ll explore its Mineral Hall and get an insider’s view of its collections area, including the normally off-limits “goodie room” with its standout specimens. The museum’s expert curators will also explain their research into new minerals and the causes of diamond color.

Our group was guided by the Mineral Sciences staff: associate curator Eloïse Gaillou, collections manager Alyssa Morgan, and curator emeritus Anthony Kampf. All have advanced degrees in their fields. Eloïse has a master’s degree in geology and a Ph.D. in materials science. Alyssa has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in geological sciences. And Anthony’s Ph.D. is in mineralogy and crystallography.

Museum Origin and History

The site now occupied by the Natural History Museum was once known as Agricultural Park. Established in the 1870s, it is described by the museum’s website as “a lawless area with horse racing, gambling, and prostitution.” That all changed when the site was renamed Exposition Park in 1910 and construction of the museum began. The Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art opened its doors on November 5, 1913. Its first mineral collection consisted of just five boxes of specimens—a donation from Los Angeles capitalist General Charles Forman.The collection grew steadily through a series of small donations. Then, in 1920, a major donation came from the Los Angeles Chamber of Mines and Oil. The collection was rich in fine specimens of copper-bearing minerals from Bisbee, Arizona.

In 1946, the museum established Mineralogy and Geology as a separate department. In 1952, the Mineral Hall was installed in the museum’s original rotunda. A series of donations over the next decade from Los Angeles jeweler William E. Phillips initiated the gem collection.

Many important donations followed, and in 1959, the museum began a campaign to build its mineral and gem collections through both donations and purchases. The source of many of the purchases was Martin Ehrmann, an important dealer in museum-quality minerals. He also sold many specimens to museum supporters, who later donated them.

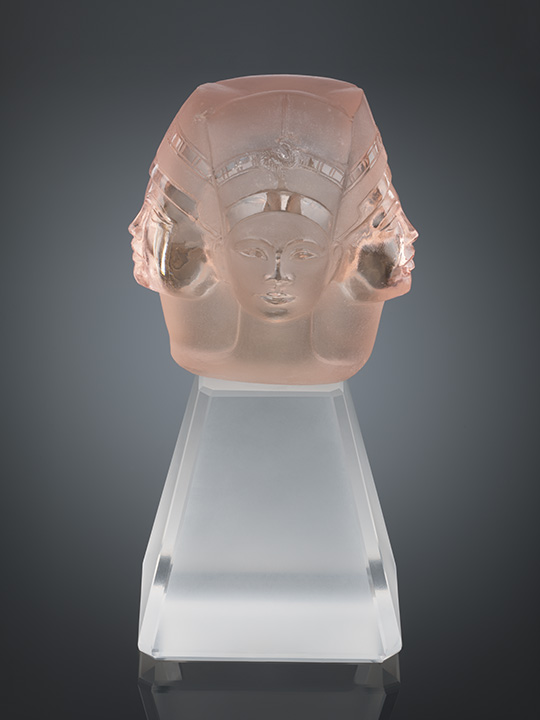

1985 marked the opening of additional gallery space known as the Deutsch Gallery: Gemstones and Their Origins. It was funded by Alex Deutsch, a pioneer in the aerospace industry, and by the Weingart Foundation. The gallery exhibits focused on explaining how gemstones form and where they are found.

Retired lawyer John Jago Trelawney donated his gem collection to the museum in 1988 and bequeathed around $450,000 to support research projects upon his death in 2001. In 2005, the exceptional Weber-Perloff collection was donated to the museum. Consisting of about 50,000 small specimens, called micromounts, it was one of the largest collections of its kind in the world. In 2010, NHMLAC received the extraordinary collection of Hyman and Beverly Savinar, which is especially rich in gem-quality crystals. In 2011, the museum received the collection of Mel and Lois Hindin, which consisted of many remarkable minerals and gems.

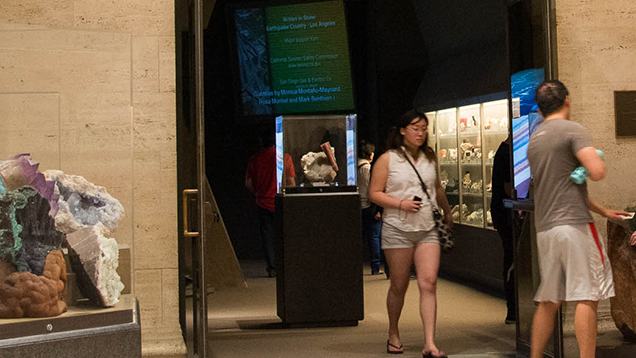

Today, the museum is a living, vibrant institution, filled with the chatter of schoolchildren as they press their noses against the display cases. But there’s much more to the museum than its public face. The off-display areas house one of the most significant mineral and gem collections in the United States.

An Overview

The museum’s gem and mineral collection consists of approximately 150,000 specimens representing about half of the world’s known mineral species. Of that number, there are about 143,000 minerals, 3,000 rocks (mineral aggregates), 3,000 gems, and 50 meteorites.The specimens come from purchases, donations, and exchanges with other institutions. The museum has specimens from around the world, including the largest and most extensive collection of California gems and minerals.

There are more than 2,000 specimens on display in the 6,000-square-foot Gem and Mineral Hall. Yet this number is dwarfed by the total of specimens available behind the scenes for research or future display. One of the major storage areas is the Collections Room.

The Collections Room

The vast majority of the museum’s mineral specimens are housed in the Collections Room. Most of them are not worthy of display, but they are invaluable to geologists and other scientists as research subjects.As collections manager for the museum, Alyssa Morgan works among rows of mineral-filled cabinets, stacked almost floor to ceiling. Her job is to maintain the collection and the database and catalog.

Users of the collection—mostly geologists and material scientists in research institutions—can request specimens related to their studies of minerals from a certain area, or of rare or unusual minerals. Samples are broken off from larger specimens and mailed to the requesting parties.

Specimens in the Collections Room are organized into several sub-collections. The general reference minerals are arranged systematically by chemical class (elements, sulfides, oxides, etc.). California specimens are arranged by locality. Small micromounts and thumbnails are arranged alphabetically by species.

Micromounts and Thumbnails

Micromounts and thumbnails are popular with an important segment of the mineral collecting world, and they are often excellent candidates for scientific research. Through large donations, especially the exceptional Weber-Perloff collection, the museum has amassed more than 100,000 micromounts—the largest such collection in the world. It includes many gold specimens, mostly from California, and more than 2,000 diamond crystals.The thumbnail collection is also quite large, consisting of about 10,000 specimens that came mostly from a single donor, Jessie Hardman, in the year 2000. Because Mrs. Hardman was determined to have a piece of everything, the collection includes many rare minerals representing a variety of rarely represented localities.

Small plastic boxes provide some protection from the environment, humidity, and other factors. Although the specimens are small, they’re valuable because of their diversity. They also require little storage space and, because of their uniform sizes, are easily organized.

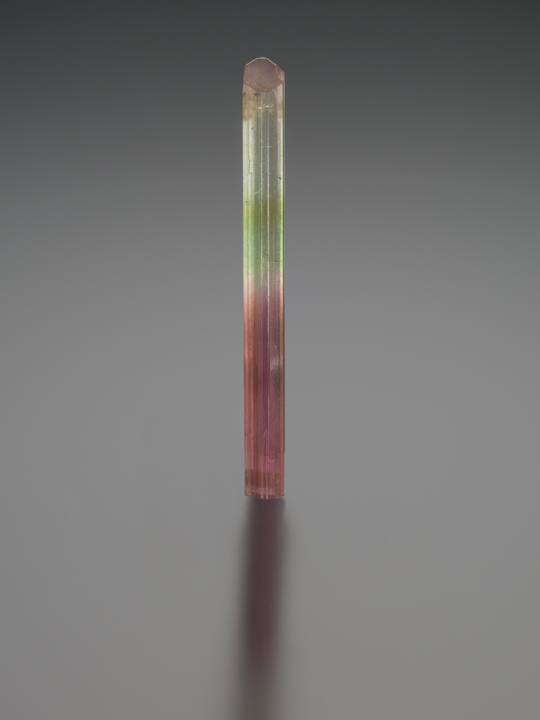

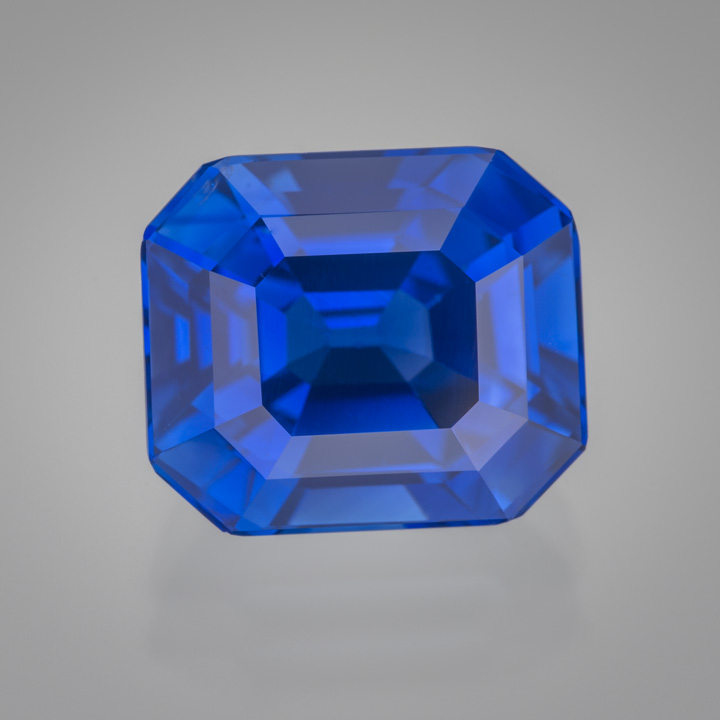

The “Goodie Room”

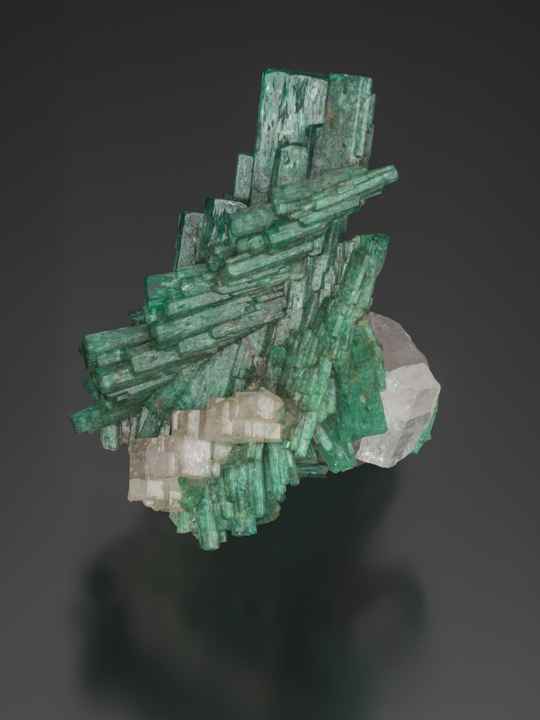

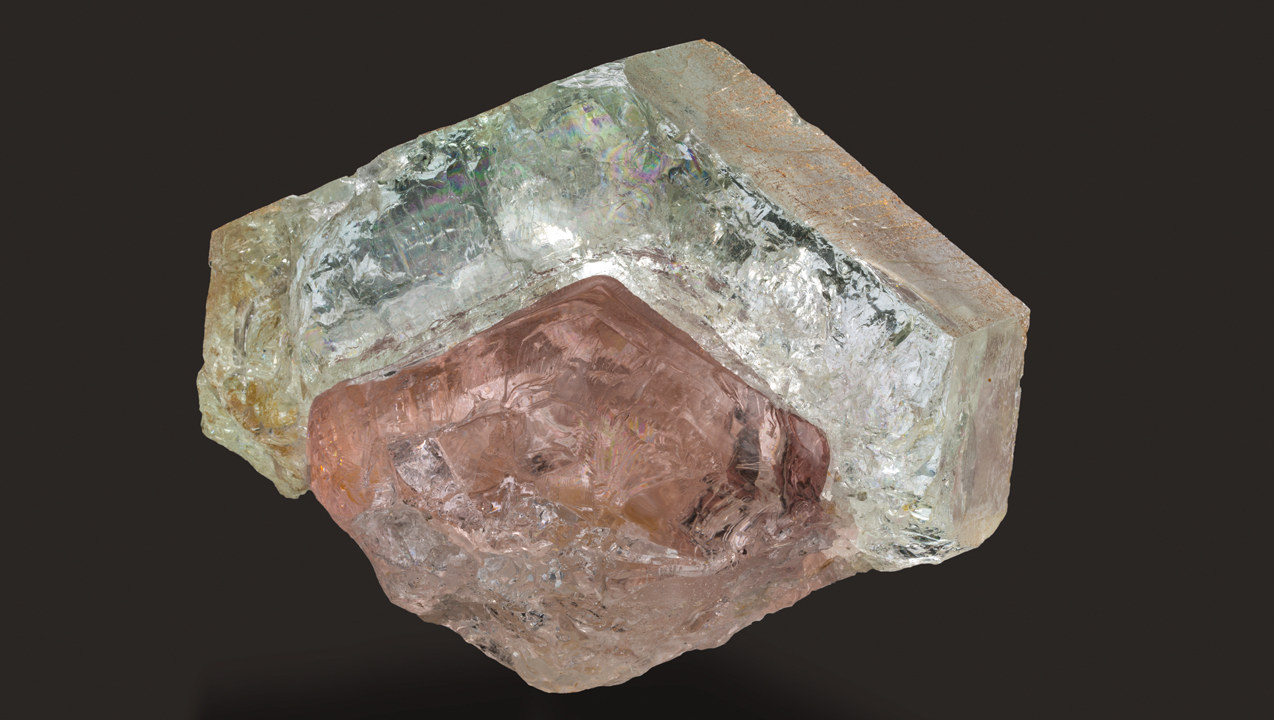

The museum’s “goodie room” is the staging area for specimens in fine, unbroken condition. Of the approximately 4,500 mineral specimens and gemstones in this room, some are not quite worthy of display and some are simply duplicates of items already on display. Some have good enough color and transparency to be suitable for faceting. For the most part, these specimens are not available to researchers for sampling.Researchers and Their Research

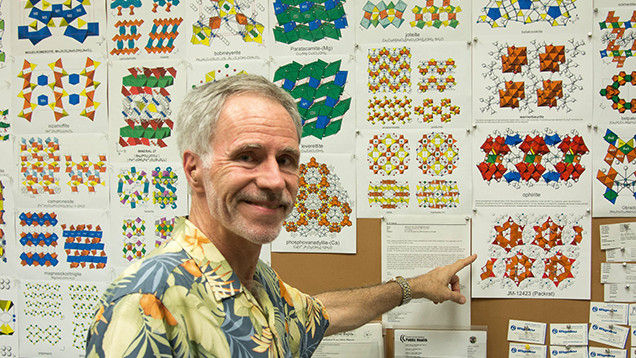

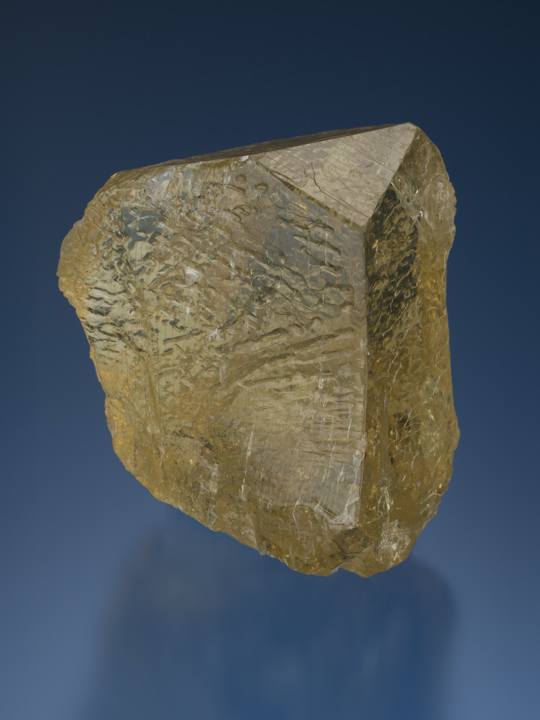

The core of any major natural history museum is the research that takes place behind the scenes. Current projects at NHMLAC include Anthony Kampf’s research into new minerals and Eloïse Gaillou’s studies on colored diamonds.Curator emeritus Dr. Anthony (Tony) Kampf joined the museum in January 1977, and helped create the world-renowned Hall of Gems and Minerals. Tony played an important role in soliciting acquisitions and arranging the galleries. He has overseen the growth of the museum’s mineral and gem collection from about 20,000 to more than 150,000 specimens.

Merilee Chapin is managing editor, Duncan Pay is editor-in-chief of Gems & Gemology, and Pedro Padua is a video producer at GIA content development in Carlsbad, California. Dr. James Shigley is a distinguished research fellow at GIA’s Laboratory in Carlsbad.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Eloïse Gaillou, associate curator of the Mineral Sciences department, Alyssa Morgan, collections manager, and Dr. Anthony Kampf, curator emeritus, all at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in Los Angeles, California, for their help and courtesy during our visit. We would also like to thank Clara Zink for assistance during the interviews recorded for this article, along with Robert and Orasa Weldon for their effort and expertise photographing the many beautiful gems and minerals in the museum’s collection.

.jpg)