Auction Houses: A Powerful Market Influence on Major Diamonds and Colored Gemstones

ABSTRACT

The world’s two largest auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, began regular sales devoted to important diamonds and colored stones in the 1970s. Through their ability to generate publicity, they have become a significant force in price and demand throughout the world, while also generating interest in fancy-color diamonds and the geographic origin of top gemstones. In the process, they have become both supplier and competitor to the world’s top jewelry houses.

INTRODUCTION

In December 2008, as most of the world plunged into an economic crisis, a historic Fancy Deep grayish blue diamond achieved the highest price ever paid for a single gemstone: $24.3 million. The sale of the Wittelsbach Blue made international headlines because it was conducted not in the privacy of a showroom but in public at an auction house in London, with the news media and dealers from around the world in attendance. The results were broadcast within seconds of the hammer fall.

Today, the highest-profile sellers of major diamonds—larger than 10 carats, both colorless and fancy-color—and top gemstones are the world’s two largest auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s. In 2011, their combined jewelry sales reached $990.1 million (“Christie’s jewelry, watch sales up 40%,” 2012; “Sotheby’s 2011 revenues rise 7%,” 2012). And while there are no reliable figures of their share of large stone sales, for more than two decades the auctions have been a major competitor to the world’s leading jewelry houses such as Cartier, Harry Winston, and Van Cleef & Arpels.

Auction sales have also had a profound effect on the diamond and gem markets, influencing both prices and consumer sentiment (Rapaport, 2008). In doing so, they have promoted awareness of fancy-color diamonds and country of origin for colored stones among buyers and dealers worldwide (King, 2006; R. Drucker, pers. comm., 2012).

In the four years since the sale of the Wittelsbach Blue diamond, which was immediately renamed the Wittelsbach-Graff, a number of price records have been broken. Less than a year later, a 24.78 ct pink diamond commanded $46 million. And the media attention paid to the Wittelsbach-Graff (figure 1) was dwarfed by the coverage lavished on the December 2011 sale of actress Elizabeth Taylor’s jewels.

BACKGROUND

The two auction houses have histories dating back to the 18th century. Sotheby’s began in 1744 when London bookseller Samuel Baker auctioned the rare book collection of a British aristocrat. After Baker’s death in 1778, his business partner George Leigh and his nephew, John Sotheby, assumed control (Live Auctioneers, 2010). Sotheby’s expanded beyond books to include prints, medals, and coins, and by the mid-19th century it had begun to rival Christie’s in the fine art world.

James Christie was a London art dealer who in 1766 established an auction business to trade artworks. Both Baker and Christie understood that the key to success in the auction trade was establishing strong connections with titled society. But Christie established the importance of provenance—an item’s prestigious history or connection to an important person—as a value-adding proposition (Baptist, 2011). Christie’s first sale of fine jewelry came in the aftermath of the French Revolution. In 1795, it auctioned the many jewels of Madame du Barry, King Louis XV’s mistress, who had been executed two years earlier. That sale realized £8,791, the equivalent of $1.3 million today (F. Curiel, pers. comm., 2012).

Fine art was the mainstay of both houses through the 19th and early 20th centuries. Indeed, it remains their largest category. The auction houses occasionally handled top jewelry pieces, when nobility were obliged to sell some of their treasures—for example, Christie’s 1875 sale from the gem collection of the Duke of Marlborough, which brought £36,750, equivalent to about $4.5 million today (F. Curiel, pers. comm., 2012).

A review of pre-1965 catalogs shows that most major jewelry auctions up to that time were conducted at Christie’s and Sotheby’s headquarters, both in London. Jewelry items were usually included as part of larger auctions of wealthy estates, in tandem with objets d’art, furs, and other luxury goods (Baptist, 2011). In the late 1960s, the houses began holding separate sales for large gems and major jewelry pieces. These were conducted in Geneva, which became the main venue for both houses until they established similar events in New York. Yet most top jewels of the royalty were still sold through established jewelers such as Cartier, Harry Winston, and Van Cleef & Arpels, which had connections to European royal families, and later to wealthy families and celebrities in the United States and Latin America.

Parke-Bernet, a New York auction house founded in 1937 by noted art dealers Hiram Parke and Otto Bernet, was the first to hold regularly scheduled sales dedicated to jewelry. In its first “Precious-Stone Jewelry” sale, held in 1938, all 60 of the lots on offer came from an estate. The auction catalog (figure 2) shows the finished pieces described in some detail, including cut styles and approximate carat weights. But none of the lots carried price estimates, and little gemological information was offered, beyond grouping sapphires as “Ceylon” or “Oriental” (Parke-Bernet, 1938).

AUCTIONS AS MARKET INFLUENCER

The first “celebrity” gem auction occurred 31 years later. A 69.42 ct diamond sold by Parke-Bernet made worldwide headlines in October 1969, when it became the first gemstone to break the million-dollar barrier at public auction. It was also one of the first significant diamonds graded by a gemological laboratory, carrying a GIA report with a grade of E-F Flawless (Parke-Bernet, 1969). The diamond had already gained some notoriety, if not a name, by having been cut from a 240.8 ct rough by Harry Winston in 1966. The first cleaving of the diamond was done before television cameras. After Winston’s cutters completed their work, the company sold the 69.42 ct pear-shaped diamond to Harriet Annenberg Ames the following year. Ames put the gem up for auction in 1969, saying she did not like it languishing in a bank vault. After a round of spirited bidding, Cartier bought the diamond for $1,050,000 (Balfour, 2009; figure 3).

The underbidder for this diamond was a representative for actor Richard Burton, who had dropped out after the bidding surpassed the million-dollar mark. Burton instead bought the stone from Cartier the following day, but gave the retailer permission to display the diamond in its showroom for one week. Publicity surrounding the diamond’s auction price, and the celebrity aura of the renamed Taylor-Burton diamond, brought out the crowds. An estimated 6,000 people lined up daily at Cartier’s New York and Chicago stores, to view the stone.

That same year, Christie’s New York created a specialty jewelry department and held its first sale in May. Like Parke-Bernet’s jewelry auctions, the offerings came exclusively from estates. The catalogs contained only a few photos, mostly black-and-white, with no price estimates and only terse descriptions. The sales were as basic as the catalogs, attended by a small coterie of local dealers (Shor et al., 1997). Sotheby’s, which had acquired Parke-Bernet in 1964, continued its jewelry auctions under the latter banner into the 1970s, when the house became Sotheby Parke-Bernet.

In the 1970s, the world economy was beset by inflation and languishing stock prices, which prompted investors to turn to hard assets—starting with exchange-traded commodities such as gold and silver, followed by gemstones. Private buyers began bidding on important stones at auctions as investments (Edelstein, 1989), and prices for top gemstones were soaring by the late 1970s. Yet the auction houses, which dealt only in estate pieces with very restricted supply, remained at the fringe of this bubble. The vast majority of their clientele still consisted of local dealers, major jewelry houses buying back their own pieces for inventory, and important estate jewelry dealers such as A La Vieille Russie and J. & S.S. DeYoung. Still, business was booming for the auction houses. Christie’s New York branch sold $2 million in 1977, a total that jumped to $8 million in 1978 and $10.6 million the following year. In Geneva, which was still the primary venue for jewelry auctions, Christie’s recorded a total of $57.2 million in 1979, nearly three times its 1978 total (Donohue, 1980b; F. Curiel, pers. comm., 2012). Meanwhile, Sotheby’s New York achieved jewelry sales of $18 million in 1979—a new record—while Christie’s New York reported sales of $10.6 million and another competitor, William Doyle Galleries, sold an estimated $3 million.

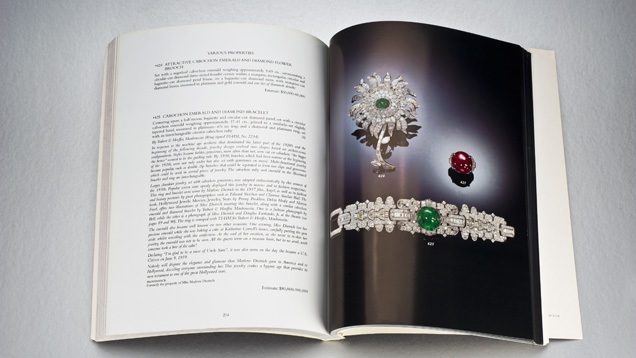

As the amount of jewelry consigned to auctions increased, Christie’s and Sotheby’s segmented their sales into a value hierarchy. These categories, from lowest to highest value, were Fine, Important, Highly Important, and Magnificent jewelry. The two houses set a regular schedule for their most important sales in New York and Geneva, where they had the largest international following. Each would offer one Magnificent Jewels sale, generally featuring some pieces expected to bring $500,000 or more, in the spring and fall seasons. Just before the close of each season, they would follow up with a Fine Jewelry sale.

In October 1979, a two-day Magnificent Jewelry sale at Sotheby Parke-Bernet in New York garnered network news coverage for a 22.30 ct emerald-cut diamond that was expected to bring $1 million. The hammer price fell just short of that mark, but with the house commission, the final price was $1,072,500 (“Auction fever,” 1979). The sale also included a 6.75 ct marquise-cut diamond that went for $319,000, or $47,260 per carat—an extraordinary price for that time.

As jewelry auctions grew substantially, mainly in finished pieces, the heightened media attention led many dealers to recognize that these sales represented a new market channel—both source and competitor (Donohue, 1980b). Dealers of estate and antique jewelry feared that the auction houses, with their ability to generate national publicity, could take over the high-end segment of the industry. By now at least half of the bidders on estate pieces were private rather than trade buyers. Retail jewelers who handled such goods claimed they could not pay auction prices, especially for highly desirable pieces that resulted in a bidding war (Donohue, 1980b).

Gem dealers also described the “auction effect”: price bumps for top-quality diamonds and gemstones after similar goods had achieved high prices at a publicized auction, particularly as diamonds and gemstones were being touted as investment pieces during this inflationary period (Donohue, 1980a). A record-setting Christie’s sale in Geneva in 1979 illustrates this effect. At the event, a 4.12 ct Burmese ruby sold for $414,832—the first time a colored gemstone attained more than $100,000 per carat at auction (and fell nearly 50% within a few months, especially for top qualities. The slowdown hit the auction houses as well. Auction sales barely made their pre-sale estimates, and the percentage of unsold lots rose sharply (Blauer, 1981). Buyers began seeking only the “very special” pieces signed by prestigious houses such as Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Bulgari, and shied away from loose stones altogether as prices declined. During the recession, the auction houses focused on their mainstays of classic period jewelry, particularly Art Deco and Art Nouveau pieces from the top jewelry houses (Blauer, 1983).

By the end of 1983, the market for top gemstones had stabilized. These goods began to resurface at the auctions, but now there were two important differences. Fancy-color diamonds, which had once only interested collectors and connoisseurs, were being offered. And the buyers were a new breed of players, luxury jewelry houses such as Laurence Graff, Moussaieff Jewellers, and Robert Mouawad. These jewelers found the auctions helpful in two ways: as a source of important stones, and as a way to focus publicity on their own growing businesses.

Sotheby’s October 1983 New York sale of $8.5 million matched a 1979 record. Meanwhile, Christie’s reported overall record sales for the first half of 1983—40% over the previous year (Shor, 1983). In 1984, Sotheby’s and Christie’s sold a total of $70 million in gems and jewelry in New York alone, nearly doubling their volume within two years (Gertz, 1985).

The transformation of the jewelry auction business into the market-leading role came in 1986-1987, when two things happened.

First, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, which had by now dropped Parke-Bernet from its name, recognized that the key to growth was moving beyond estate goods and into newly mined and cut stones—diamonds over 10 carats and major diamond necklaces containing 50 carats or more of high-quality stones. To a lesser extent, they also commissioned jewelry houses to create major ruby, sapphire, and emerald pieces (Shor et al., 1997).

In 1986, Christie’s began aggressively soliciting dealers to list important stones in its major sales, as a supplement to the estate pieces. Sotheby’s, which had accepted dealer consignments on a limited basis, redoubled its efforts to secure trade goods, a move that enabled their combined sales to grow from about $100 million that year to $500 million within a decade (Shor et al., 1997). In short, the auction houses became retailers of newly cut stones.

The immediate effect was that the 1986–87 auctions brought an influx of very large diamonds—all from dealers rather than estates (Shor, 1988). Four D-Flawless diamonds over 50 carats came up for auction during those two seasons, whereas previously only one or two such stones would appear in the course of a decade. The reason behind this influx was that De Beers had resumed selling the very large diamonds it had stockpiled during the early 1980s, when prices were depressed. The company also changed its mining and rough sorting procedures to reduce breakage of large stones (Shor, 1988). Dealers started putting these stones up for auction, claiming they could get higher prices there. The catalyst for this was a 64.83 ct D-IF diamond that brought $6.3 million at Christie’s October 1986 New York sale. It was a record price (soon broken) and attracted more large stones at subsequent sales.

By now, extremely wealthy private buyers were returning to the auction houses to buy jewelry. Many of these private buyers engaged in bidding competition, often becoming emotional, while dealers tended to be much cooler and stay within their spending limits so they could realize a profit (Shor, 1988). But in a bullish market, even seasoned dealers can get caught up in the competitive spirit and surpass their own limit, especially when bidding against another dealer (Rapaport, 2012).

Finally, dealers rushed to consign major stones because they felt they could insist on setting reserve prices high—generally at the price they would set in their own office, making the transaction ostensibly risk-free. Yet some dealers found that if their stones failed to sell, the failure received almost as much media attention as the successes, putting a stigma on those goods (Shor, 1988).

The second turning point that established auction houses as a major force was the most publicized jewelry event up to that point: the April 1987 sale of the jewels of the Duchess of Windsor (Schupak, 2011).

The Duchess, formerly Wallis Simpson, had been an international celebrity since 1937, when King Edward of England abdicated his throne to marry her. In their 35 years of marriage, she amassed a large collection of jewels from the major jewelry houses, many of them immortalized in photographs (figure 4). Edward, the Duke of Windsor, died in 1972, and after the Duchess’s death in 1986, her jewelry collection was sent to Sotheby’s in Geneva for auction.

The Duchess of Windsor sale was scheduled for April 2–3, 1987. The presale estimate for the collection was $7 to $8 million. Sotheby’s divided the collection into 305 lots, including 87 pieces signed by Cartier (the Duke and Duchess’s favorite jeweler) and 23 items by Van Cleef & Arpels. Media coverage was heavy, with most major networks around the world airing preview features about the legendary jewelry collection and reporting from the sale. A New York Times Magazine piece from February 1987 reported the history of the major pieces. The notoriety of some of the buyers, which included Elizabeth Taylor and Laurence Graff, also attracted media attention (Vogel, 1987).

After the bidding was over, the total came out to $50.3 million—seven times the pre-sale estimate. Iconic pieces such as Cartier’s sapphire “Panther” brooch (figure 5) and “Flamingo” brooch (figure 6) achieved 15 times their pre-sale estimates. Twenty-three years later, Sotheby’s grouped 20 items from the sale into a second auction that realized $12.5 million and garnered another round of international press coverage. The record prices stemmed from the Windsor jewels’ extraordinary provenance, which generated bids worth many times the intrinsic market value of the pieces (Schupak, 2011).

The reverberations from the Windsor sale boosted prices and demand and “got the world emotionally involved in jewelry,” according to one major diamond dealer (Shor, 1988). One auction executive said the sale put jewelry in the same league with Impressionist paintings, historically the top-selling category. The auction houses put their considerable public relations abilities to use, generating the type of mystique Harry Winston had evoked a generation earlier (Shor et al., 1997). They also began proactively reaching out to potential buyers: dealers of significant gems and the wealthy clientele who also collected art, antique furniture, rare wines, and watches from their other departments.

The immense publicity generated by the Duchess of Windsor sale, and the auction houses’ aggressive moves to capture a greater share of the top jewelry market, attracted numerous private clients. By the mid-1990s, at least half the buyers at major auctions were purchasing for themselves. At the same time, Sotheby’s and Christie’s determined efforts to obtain consignments gave them a clear market dominance in top jewelry over competing firms such as William Doyle Galleries, Butterfields, and Skinner Galleries (Shor et al., 1997).

Although auction sales grew substantially though the 1970s and 1980s, auction executives point to the Windsor sale as the watershed event that permanently established auction houses as major players in the top jewelry market (Schuler, 2011). The event demonstrated the auction houses’ global reach in attracting bidders and promoting sales. From a total of about $300 million in jewelry auction sales in 1988, Christie’s and Sotheby’s combined to reach $500 million within seven years.

After the Windsor sale, emotions continued to soar as bidders pushed prices of top goods to record prices. Within weeks, the 0.95 ct Hancock Red diamond (figure 7) became the most expensive per-carat gemstone ever sold at auction. The hammer came down at $880,000—a remarkable $926,315 per carat, eight times its pre-sale estimate. In 1989, a 32.08 ct Burmese ruby brought $4.62 million, five times its pre-sale estimate (Blauer, 2012).

Aside from pushing up prices, selling at auction held another attraction for dealers of top colored stones and diamonds: The auction houses paid quickly during a time when retailers were demanding longer and longer memo terms (Shor, 1998).

The jewelry auction catalogs, once very basic, were now being given the fine art treatment, with full-color illustrations and more detailed descriptions. The following year brought another addition to the catalogs. In 1988, both houses began listing country of origin reports on many of the major untreated rubies and sapphires (emeralds followed later), along with background on the rich histories of Burmese rubies (see Enriquez, 1930) and sapphires from Kashmir and Ceylon. Before then, geographic origin notations were very sporadic. As auction houses recognized the historic premium on gemstones from certain localities, they sought to envelop these top stones in a historical mystique that mimicked the provenance of an estate jewel. A 15.97 ct ruby, offered by Sotheby’s at its October 1988 New York auction (figure 8), carried the following description:

The ruby sold to Graff for a record per-carat price of $227,301, or $3.63 million total.

Publicity surrounding the sale of this and other important gemstones at auction has broadened the awareness of geographic origin among buyers and retailers, increasing the premiums for stones such as untreated Burmese rubies, Kashmir and Burmese sapphires, and Colombian emeralds. Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction results are always public, so record prices generate big headlines and promote consumer awareness of these special gems. Auctions would not have the same market influence if the results were private. The auction influence was not all in one direction, however. As ruby and sapphire treatments proliferated during the 1980s, the auction houses responded to trade demand by adding more treatment information for the important gems offered in their sales (Shor et al., 1997; R. Drucker, pers. comm., 2012).

Historically, diamonds larger than 50 carats have been exceptional rarities. Between 1990 and 1995, however, the market saw more 50-plus ct diamonds than the known total since Jean-Baptiste Tavernier began cataloging large diamonds in the mid-17th century (Shor, 1998). Many of them began appearing at auction, and some achieved strong prices. But after a 101 ct D-Flawless heart shape failed to draw the seller’s $10 million reserve price at a 1996 Christie’s New York auction, it became apparent that neither dealers nor private buyers would keep paying such lofty prices. Laurence Graff, the likely buyer for such a stone, noted that dealers had gone too far in their asking prices (Shor, 1998).

CONTROVERSY OVER PRICING

Fine jewelry houses, which used the auctions as a source for large stones as well as some of their own historic pieces, began feeling the competition. Several complained that dealers who had previously supplied them now wanted to put their best pieces at auction. In addition, Sotheby’s and Christie’s began engaging in more direct competition with retailers by setting up departments to sell large diamonds and major jewelry pieces directly to clients, outside of the auction process (Shor et al., 1997). The auction houses’ critics added a more serious charge, alleging that many of the pieces signed by famous jewelry houses or designers (Schlumberger, Webb, and the like) were actually forgeries made by consignors, or “reconstructions” where a large piece was built around a much smaller one with an authentic signature. Some retailers also claimed that auction houses sold treated gemstones without proper disclosure (Shor et al., 1997).

As the houses moved to address these complaints—auction catalogs showed a substantial increase in the number of diamonds and colored stones with reports from gemological labs—more serious issues emerged. The near-total dominance of Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the fine art and jewelry worlds, combined with their similar sale dates, consignment fees, and sales commissions, eventually attracted the attention of European and U.S. regulatory agencies.

Allegations of fee-fixing actually went back to 1975, when Christie’s imposed a 10% buyers’ premium and Sotheby’s immediately followed, which brought lawsuits from the Society of London Art Dealers and British Antique Dealers’ Association (Ashenfelter and Graddy, 2005). But the collapse of the fine art market in the early 1990s brought an era of cutthroat competition between the two houses in the form of slashed buyers’ fees, donations to consignors’ favorite charities, and even loans to potential consigners. During this period, CEOs Christopher Davidge of Christie’s and Diana Brooks of Sotheby’s met to discuss a truce. Sotheby’s subsequently abandoned its loans and charitable donations to consignors. In March 1995, Christie’s imposed a non-negotiable sellers’ commission, ranging from 10% for items under $100,000 down to 2% for items that sold for more than $5 million. Sotheby’s delayed following suit and won a $10 million jewelry consignment before instituting a similar commission.

In 1996, the UK’s Office of Fair Trading announced an inquiry into possible anti-competitive practices, which ultimately led to Davidge’s resignation from Christie’s in December 1999 (Ashenfelter and Graddy, 2005). News reports soon began circulating that Davidge had made a deal with the U.S. Department of Justice to testify in a four-year investigation into charges of price-fixing. The Justice Department’s report (2001) noted that the two houses controlled more than 90% of the auction market for fine art and jewelry.

Davidge’s cooperation brought immunity from prosecution for himself and other Christie’s executives, with the exception of board chairman Anthony Tennant. But Tennant could not be extradited to the United States, because price-fixing is a civil rather than a criminal matter in the UK (“Sir Anthony Tennant,” 2011). Meanwhile, the Justice Department pursued Sotheby’s majority owner and chairman, A. Alfred Taubman, and CEO Diana Brooks. Brooks, who agreed to testify against Taubman, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three months’ probation, six months’ house arrest, 1,000 hours of community service, and a $350,000 fine (Ackman, 2002). Taubman was sentenced to a year in federal prison but was released after nine months (Johnson, 2007).

Yet these legal problems did not topple Sotheby’s and Christie’s dominance of the jewelry and fine arts auction markets, as evidenced by their sales over the following decade. The houses did change commission rates and separate their sales dates, which had been closely intertwined (Ashenfelter and Graddy, 2005). Sotheby’s eventually moved its major fall auctions from October to November and December to better accommodate the wishes of private buyers (Schupak, 2011).

| Box A: Auction Record Prices |

| Prices for major diamonds and colored stones sold at auction can vary widely, even among gems of similar quality. Influencing factors include provenance, buyer competition, and market mood. The highest per-carat price for a colorless diamond sold at auction is from the Elizabeth Taylor sale in 2011. It sold for more than double the per-carat price ($265,697 vs. $138,526) of a diamond with similar size and quality auctioned a year earlier. The most expensive gem ever sold at auction, a 24.78 ct Fancy Intense pink diamond, had no historical ties. But it was exceptionally rare, being one of the largest pink diamonds ever offered for sale. Below is a list of the record-breaking prices for gemstones sold at auction. Total price for any gem: $46,158,674 24.78 ct Fancy Intense pink diamond, Sotheby’s Geneva, November 16, 2010 Per-carat price for any gem: $2,155,332 5 ct Fancy Vivid pink diamond, Christie’s Hong Kong, December 1, 2010 (the “Vivid Pink”) Total price for a colorless diamond: $21,506,914 76.02 ct D-IF, Christie’s Geneva, November 13, 2012 (the “Archduke Joseph”) Per-carat price for a colorless diamond: $282,545 76.02 ct D-IF, Christie’s Geneva, November 13, 2012 (the “Archduke Joseph”) Total price for a pink diamond: $46,158,674 24.78 ct Fancy Intense pink, Sotheby’s Geneva, November 16, 2010 Per-carat price for a pink diamond: $2,155,332 5 ct Fancy Vivid pink, Christie’s Hong Kong, December 1, 2010 (the “Vivid Pink”) Total price for a blue diamond: $24,311,190 35.56 ct Fancy Deep grayish blue VS2, Christie’s London, December 10, 2008 (the “Wittelsbach Blue”) Per-carat price for a blue diamond: $1,439,497 10.95 ct Fancy Vivid blue, Christie’s New York, October 20, 2010 (the “Bulgari Blue”) Total price for a yellow diamond: $12,361,558 110.03 ct Fancy Vivid yellow VVS1, Sotheby’s Geneva, November 15, 2011 (the “Sun Drop”) Per-carat price for a yellow diamond: $367,366 2.62 ct Fancy Vivid yellow, VVS1, Christie’s New York, December 13, 2011 Total price for a ruby: $4,620,000 6.04 ct Burmese, Christie’s Hong Kong, May 29, 2012 Price for a sapphire: $7,122,742 130.50 ct, Christie’s Geneva, May 18, 2011 Per-carat price for a sapphire: $145,339 A pair, 14.84 ct and 13.47 ct Kashmir, Christie’s Hong Kong, May 31, 2011 Note: A 26.41 ct Kashmir sapphire achieved virtually the same per-carat price at Christie’s Hong Kong on November 29, 2011. Price for an emerald: $6,578,500 23.46 ct Colombian, Christie’s New York, December 13, 2011 (Elizabeth Taylor sale) Per-carat price for an emerald: $280,000 23.46 ct Colombian, Christie’s New York, December 13, 2011 (Elizabeth Taylor sale) |

THE 21ST CENTURY

At the dawn of the new millennium, the number of ultra-wealthy people increased worldwide, especially in emerging parts of the world. The newly rich in Russia and several former Soviet states, China, and Middle East trade centers such as Dubai, Bahrain, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi joined a growing list in Europe and the U.S., where the number of high net worth individuals increased 48% during the 2000s. This burgeoning wealth, combined with price speculation, created a “perfect storm” for luxury jewelry sales at auction (Rapaport, 2008; Shor, 2008).

Asia in particular enjoyed rising wealth. During the 1980s, Asian economies, following the lead of Japan, began a period of strong growth in South Korea, Thailand, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong, which remains the major regional trading center. Taken as a whole, their economies grew an average of 5.5% annually between 1965 and 1990, one of the longest sustained growth periods of any region in history (Radelet et al., 1997). With the developing wealth in Asia, where there is an extremely high savings rate and jewelry is traditionally viewed as an asset rather than a consumable, demand for fine jewelry surged (Shor, 1997; Shor et al., 1997). As a result, Asian buyers were becoming major buyers of jewelry across the board, including the major jewelry auctions.

Christie’s held its first major jewelry auction in Hong Kong in 1992. Sotheby’s, which had opened a Hong Kong sales room devoted mainly to Asian art in 1973, began holding major jewelry auctions there shortly after Christie’s. By the 2000s, Hong Kong stood alongside Geneva and New York as a venue for the Magnificent Jewelry sales, where the costliest lots are offered. By 2010, Hong Kong was Christie’s leading jewelry venue, with annual sales totaling $163 million (Christie’s, 2010). According to its Sotheby’s 2011 annual report, Hong Kong accounted for 18% of the company’s total sales in 2011, triple the share from 2007. Asia, including mainland China, has become a leading buyer of fancy-color diamonds, large colorless diamonds, and top gemstones, along with traditional favorite jadeite (Christie’s, 2010).

Many of the auction headliners of the past 15 years have been fancy-color diamonds, which captured the market’s attention and bidders’ funds. The watershed for fancies was the record price achieved by the Hancock Red in 1987, which heightened global interest in colored diamonds. Following the sale, auction houses increased their offerings of colored diamonds with top grades. These quickly commanded the highest per-carat prices of any gemstones offered for sale (King, 2006). Indeed, during the past decade, nearly every major auction in the three main venues—Geneva, New York, and Hong Kong—has featured at least one significant fancy-color diamond.

Prices at auction soared through the 1990s and into the 2000s, fed by the burgeoning number of ultra-high net worth individuals. Prices for colored diamonds doubled and kept rising. The $1 million per-carat barrier was crossed in 2007, when Christie’s sold a 2.26 ct Fancy purplish red diamond for $2.67 million, or $1.18 million per carat. Nor were record prices limited to colored diamonds. Burmese rubies and large colorless diamonds also saw substantial increases. In 2006, an 8.62 ct Burmese ruby sold for $3.64 million, or $422,000 per carat. Colorless diamond broke the $100,000 per-carat mark in 2005, and nearly doubled that by 2011. Indeed, while the financial crisis of September 2008 slowed economic activity around the world, it seemed to have little effect on auctions. Just three months after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the Wittelsbach Blue diamond achieved the highest price ever paid for any gemstone when Christie’s auctioned it in London.

While the Wittelsbach diamond enjoys a rich history and a royal provenance, unpedigreed diamonds such as a 5.00 ct Fancy Vivid pink diamond doubled the $1 million per-carat mark to sell for $10.8 million at Christie’s Hong Kong. The newly named Star of Josephine, a 7.03 ct Fancy Vivid blue, went for $9.49 million in May 2009 at Sotheby’s Geneva (Burwell, 2011).

If 2009 was an unexpected banner year for jewelry auctions, 2010 shattered records. In November of that year, Sotheby’s Geneva saw the first single-day auction to top $100 million. Nearly half of the total came from a 24.78 ct Fancy Intense pink diamond that Graff won with a top bid of $46.16 million, topping the Wittelsbach for the highest price ever paid for a gemstone at auction. And just before that sale, a 10.95 ct Fancy Vivid blue diamond, the Bulgari Blue, became the third-highest-priced gemstone to sell at auction, with a $15.76 million hammer price (Blauer, 2010).

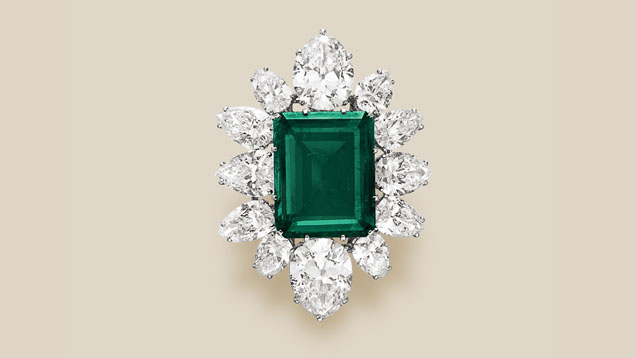

The sales records set in 2010 did not last long. On December 13 and 14 of the following year, Christie’s auctioned the jewelry of famed actress Elizabeth Taylor, who lived virtually her entire life in the headlines. The two-day sale (figure 9) saw 270 lots bring a total of $156.8 million. One of the top lots, the 33.19 ct D-VS1 Elizabeth Taylor diamond, shattered the per-carat price record for a colorless diamond—$265,697 for a total of $8.8 million. A Bulgari brooch set with a 23.46 ct Colombian emerald (figure 10) sold for nearly $6.58 million, the highest price paid for an emerald at auction (The Collection of Elizabeth Taylor, 2011). That auction also saw the most expensive natural pearl ever sold at auction, the 500-year-old La Peregrina (figure 11), which earned $11.8 million.

Like the Windsor auction, the Elizabeth Taylor sale received worldwide media coverage. The headlines and the record prices were broadcast around the world by television and print media, along with numerous Internet reports and blog posts.

The spring of 2012 saw more records fall. On May 29 at Christie’s Hong Kong, a private buyer paid $3.33 million for a 6.04 ct Burmese ruby. At $551,000, this was the highest per-carat price ever paid for a ruby at auction. That same auction saw the Martian Pink, a 12.04 ct Fancy Intense pink named by Harry Winston in 1976, sell for $17.4 million, or $1.44 million per carat (Christie’s, 2012).

In November 2012, even Elizabeth Taylor was upstaged, when a 76.02 ct colorless diamond that once belonged to Austrian royalty brought $21.5 million at Christie’s Geneva. This was an all-time high for a colorless diamond, as well as a record per-carat price of $282,545. Sold to a private, anonymous buyer, the Archduke Joseph diamond (figure 12) was believed to have been mined centuries ago at India’s famed Golconda mines (Shor, 2012).

Auction house executives offer three primary reasons why prices keep rising past record levels, even while the world economy has stagnated. The first is international reach. Whether conducted in Geneva, New York, or Hong Kong, the auctions now attract a worldwide clientele. Hong Kong, once a niche venue that specialized in jade and Chinese art, was Christie’s leader in jewelry sales for 2009 and 2010. Many of the top lot buyers were Chinese businesspeople venturing internationally for the first time. Geneva and New York also turned in record numbers as lots went to buyers from 30 countries during 2011.

Another reason is the rarity of top diamonds, especially blues and pinks. Of the millions of diamonds mined each year, only .001% qualify as fancy colors, and only a handful of those can achieve the top grades of intense and vivid. An even smaller percent are larger than a carat, let alone 5 carats. This exceptional rarity appeals to the growing number of collectors and investors.

A third factor is the shift toward the private buyer. In the past, dealers represented the majority of top-lot buyers at jewelry auctions. Today, individuals account for more than half of such sales. Auction house executives say these buyers range from collector-connoisseurs who seek the very best to investors who believe the jewels’ extreme rarity, coupled with rising demand, will continue to push the value higher (Shor, 2011).

Meanwhile, both auction houses continue to compete with retail jewelers by selling diamonds and jewels privately. Christie’s matches its clients’ buying requests to a network of dealers. Sotheby’s, in conjunction with the Steinmetz Group, a global diamond company, offers single stones or jewelry collections (Schupak, 2011).

CONCLUSION

During the past 30 years, the two largest auction houses have exerted a significant influence on the market prices for major diamonds and colored stones, while heightening interest in fancy-color diamonds and gemstones from historically prized countries of origin. The international reach and headline power of Sotheby’s and Christie’s have made them a formidable competitor to long-established jewelry houses such as Cartier, Tiffany, and Van Cleef & Arpels, while widening access to major stones for private buyers and newer high-end jewelry retailers such as Laurence Graff. Like many upscale retailers, the auction houses have adapted to technology, offering diamonds and jewelry to online buyers and displaying highlights from upcoming sales on Facebook and other social media sites. While annual auction sales have grown from less than $50 million to nearly $1 billion in those 30 years, such growth has not been accomplished without controversy and legal problems. But as the headlines surrounding the 2011 sale of the Elizabeth Taylor collection demonstrate, the auction market has become an influential force—in both demand and price—in the jewelry world today.

.jpg)