Decades-Old Synthetic Alexandrite Sheds Light on Modern Research Needs

For decades, much attention has been given to provenance studies of natural gemstones (such as emerald, ruby, and sapphire), as knowing their place of origin is significant in valuation. Synthetic colored stones do not command the same price per carat as their natural counterparts, but being able to pinpoint the growth technique and possibly the manufacturer is of value to the jewelry consumer, researcher, or collector. For example, many flux and hydrothermal producers can command a premium for their “luxury synthetics” over more quickly grown flame-fusion or Czochralski crystals.

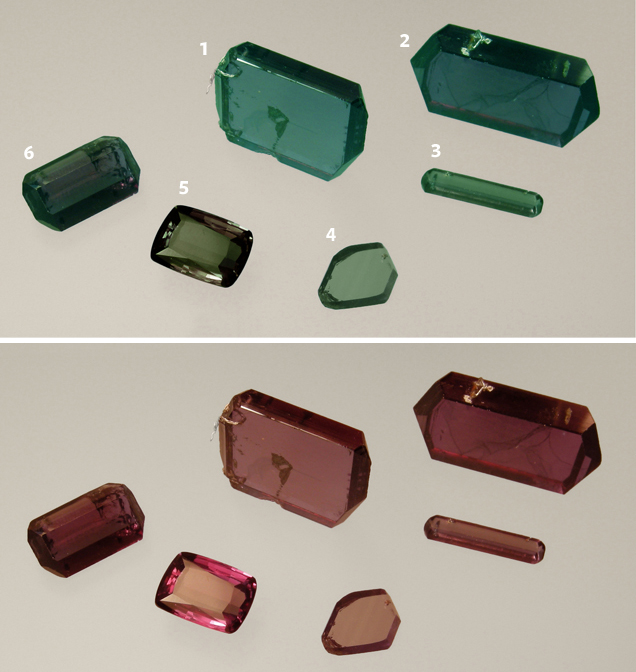

The synthetic alexandrite produced by Creative Crystals Inc. from 1971 to the early 1980s exhibited true red-green color change (figure 1), and with no production for the last 30 years, these specimens are a rarity. A recent study by Karl Schmetzer, Heinz-Jurgen Bernhardt, and Thomas Hainschwang (“Flux-grown synthetic alexandrites from Creative Crystals Inc.,” The Journal of Gemmology, 2012, Vol. 33, No. 1–4, pp. 49–81) goes into fascinating detail on the company’s history, how the seed crystals were generated, and how the crystals were grown, unlocking the mystery of the distinct growth zoning observed in these particular synthetics.

The authors’ diligence in collecting a highly representative group of samples of this out-of-production material, as well as their thorough review of the available literature, is commendable. Woven into the article are interesting tidbits about the various seed origins and orientations used for growing these alexandrites, which demonstrates how both practical considerations and research-based findings can influence production and ultimately quality. A highlight of the article is the two-page history recounted by David Patterson, a former owner of Creative Crystals.

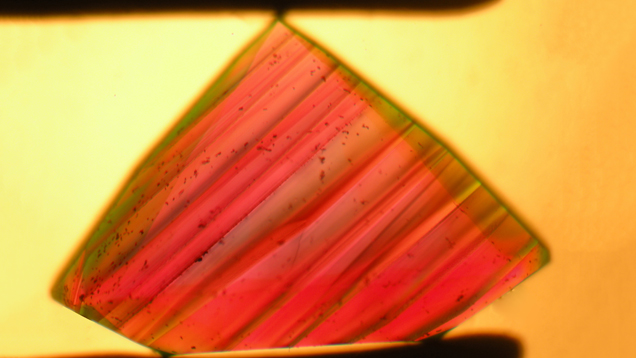

To capture the uniqueness of these synthetics, the authors conducted meticulous microscopic studies. Several other techniques—including X-ray fluorescence, electron microprobe, and ultraviolet through infrared absorption spectroscopy—were used to describe corresponding chemical and optical zoning, pleochroism, absorption bands, and inclusions. The authors draw clear correlations between growth parameters and crystal characteristics, such as the impact of seed orientation on morphology. Even more significantly, they link the previously unexplained internal growth bands (figure 2) to multiple growth cycles – the growing crystals were actually removed from the furnace repeatedly to assess their progress. Similarly, I.G. Farben grew synthetic emeralds in the 1930s using multiple growth cycles (Karl Schmetzer and Lore Kiefert, “The colour of Igmerald: I.G. Farbenindustrie flux-grown synthetic emerald,” The Journal of Gemmology, 1998, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 145–155). However, Creative Crystals would cool the melt slightly during cycles lasting one week whereas I.G. Farben would keep the melt at a constant temperature during 20-day cycles. Temperature gradients were not used to grow synthetic alexandrite for several more years, according to Dr. Schmetzer. A comparison with commercially produced flux alexandrite from Russia also illustrates how characterization techniques can reveal details of the growth process.

The article is not a light read, 33 pages in length with 46 figures and well over 100 images. But for crystal growers or those simply interested in understanding more about gem synthesis, this article serves as a window into the crystal growth engineering process and reveals how a specimen’s characteristics can shed light on its origin. Other synthetic materials have been similarly studied, and the need for such analyses continues to increase as additional synthetics and more advanced characterization techniques emerge.