Emerald: The Superstar of Trapiche Gemstones

May 17, 2019

Emerald’s verdant color is a symbol of nature’s rebirth in spring, so it is appropriately named as the birthstone for those born in May. Colombian emeralds, found deep within the Cordillera mountains of the Andes, are some of the finest emeralds in the world. They are as lush as the rainforest, mountains and valleys where they have been concealed for millennia and sought for centuries.

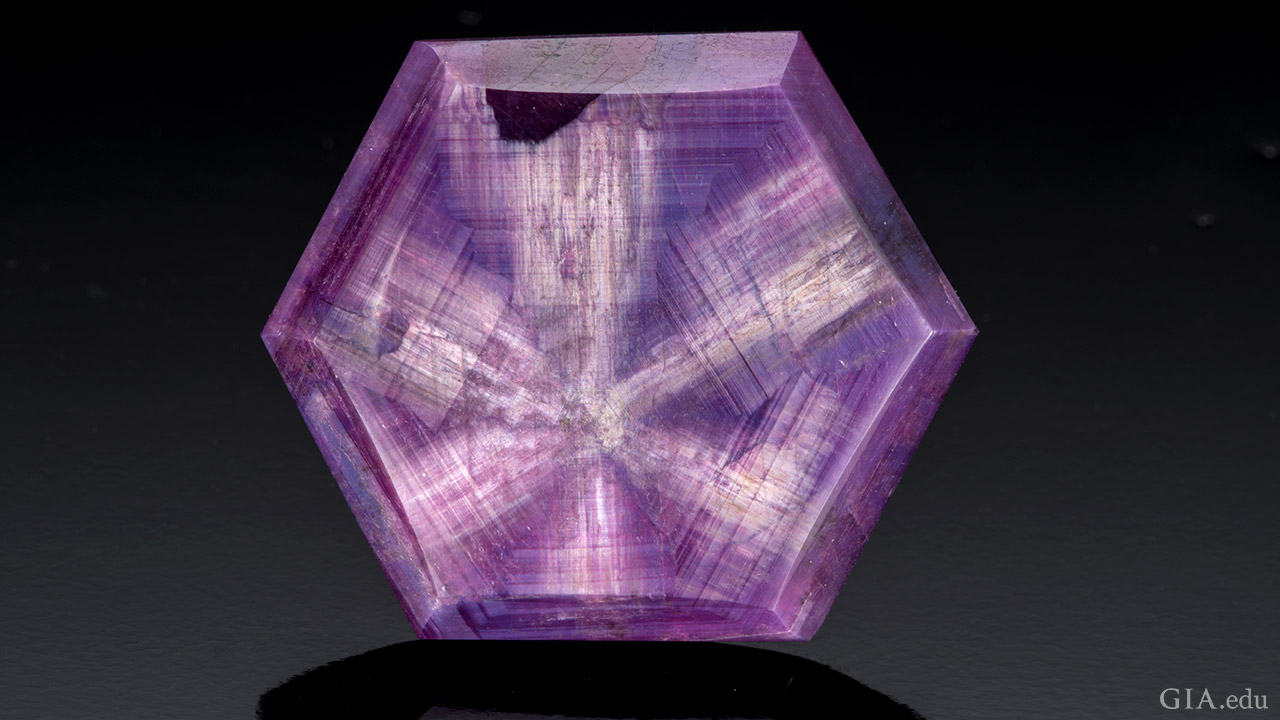

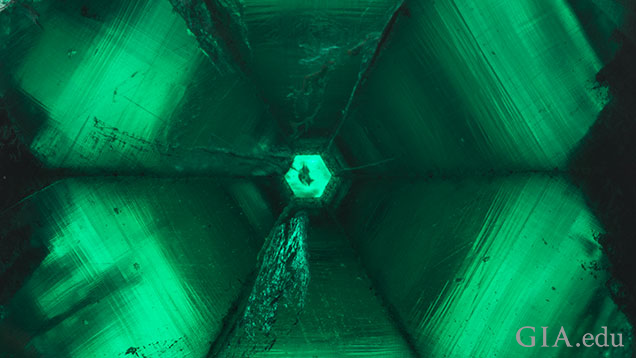

Colombian emeralds are renowned for their vibrant green color, which comes from the element chromium, and gives them their highly prized hues. When these emeralds form as a trapiche crystal – a distinct pattern resembling a wheel with six spokes – they set the standard as some of the finest and most spectacular crystals unearthed.

When emerald miners first discovered these patterned gems, they called them trapiche, the Spanish word for the multi-spoked cogwheels rotated by oxen tied to a yoke to grind cane sugar. They were first described in 1879 by French mineralogist Emile Bertrand at a meeting of the Société Géologique de France.

Trapiche emeralds are found in the black shale host rocks of just a few Colombian mines in the western belt of the Eastern Cordillera Basin. Their appearance consists of a central core, six arms and black shale dendrites – a crystalline, branching tree-like structure that forms between the arms and around the core. They are visible when the crystals are viewed perpendicular to the c-axis and are often cut as cabochons to accentuate the six partitions.

Trapiche emeralds form in the same hydrothermal conditions as other Colombian emeralds, but their texture results from a complex growth history characterized by variations of fluid pressure in the structural geology of the deposits. The crystal’s hexagonal symmetry determines the number and the development of growth sectors, giving rise to the six arms.

The arms of trapiche gems remain fixed when the gem material or light source is moved. Its six arms can intersect in the middle or radiate from a central hexagonal core. The central core of a trapiche can be open or closed and taper from small to large within a single crystal, depending on how it formed.

The six-spoke pattern in trapiche is not asterism, which refers to a gemstone phenomenon brought about by the way light interacts with oriented needle-like inclusions in the gem. The arms of asteriated gems appear to glide across the surface when the light source or gem material is moved, but the arms of trapiche gems stay in place. [Note: There are only a few known emeralds that exhibit actual asterism.]

The Many Other species of Trapiche Gems

Trapiche emeralds were first sent to GIA for analysis in the mid-1960s. Since then, the trapiche six-arm texture or pattern has been observed in a few other gemstones, most notably in sapphire and ruby.

Trapiche rubies from Mong Hsu, Myanmar were first documented by GIA in 1995 and have since been found in Guinea, Kashmir, Pakistan, Nepal, Sierra Leone and Tajikistan. Trapiche sapphires first appeared on the gem market in early 1996, when samples were offered in Basel by a Berlin gem dealer. Trapiche sapphires have been found primarily in Australian, Cambodia, China, France, Kenya, Madagascar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

All trapiche gemstones are relatively rare and some even more so. Some examples of the more rare or unusual trapiche gemstones include:

- Pezzottaite (named after mineralogist Dr. Federico Pezzotta) first appeared at the 2003 gem shows in Tucson. Since then it has become a rare, coveted gemstone by collectors worldwide. It is a member of the beryl group, along with emerald and red beryl. All three are prized when in trapiche formation.

- Tourmaline is relatively abundant in Zambia, although only a small percentage of crystals exhibit the trapiche pattern.

- Trapiche muscovite comes from only one locality, the Japanese city of Kameoka in Kyoto Prefecture, where they are locally known as “cherry blossom stones” (sakura-ishi in Japanese.)

The unique spoke pattern and variety of trapiche gemstones offer a natural geometric shape for jewelry designers looking for unusual, rare, and one-of-a-kind gemstones. None, however, can match an emerald’s majestic beauty – the superstar of trapiche gemstones.

Sharon Bohannon, a media editor who researches, catalogs and documents photos, is a GIA GG and GIA AJP. She works in the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center.