The Red Hot Gems of Summer

August 23, 2017

No color evokes more energy, action, emotion and excitement than red. It is associated with the power of fast cars, the passion of crimson roses and the seduction of summer sunsets.

Regal Red Gems

In early cultures, ruby was revered for its similarity in color to blood, the source of life. Deep red, sometimes with a hint of purple, called “pigeon’s blood” in the trade, is the most sought after shade for rubies. No colored gemstone has been more treasured by kings, queens, rulers, moguls and the upper classes than ruby. Even today, fine rubies remain an indulgence of the few.

What draws us to ruby? Does it have a mysterious quality or power – as thought by early civilizations? The scientific explanation for ruby’s subtle attraction lies in its high chromium and low iron content, which creates its red color. The chromium also causes the gem to fluoresce when viewed in ultraviolet light; in natural light, the fluorescence of high quality rubies creates an almost mesmerizing, subconscious glow, reminiscent of heat haze on a desert highway.

Red spinel, cherished by kings and emperors, also has a long and glorious history. Many famous “rubies” were actually red spinels, illustrating how very similar these gems can be in appearance. Spinels mined from 1000 C.E to 1900 C.E., in what is now known as Afghanistan, accounted for many of the red gemstones in jewelry of that era. They were called “Balas rubies,” derived from the Arabic balakhsh, for the Badhakhshan region in Afghanistan where the gem was found. The quality of natural spinel has gained notice and appreciation in recent years, so its presence and value in the market has also increased.

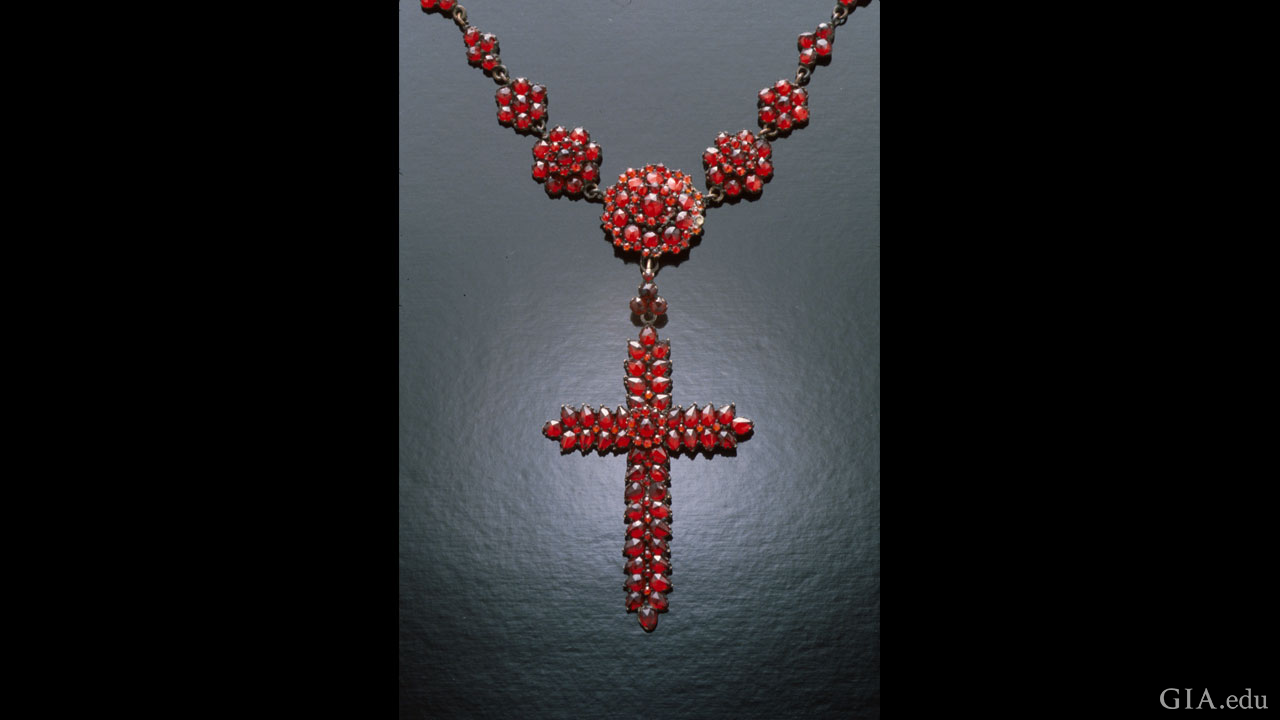

Red garnet necklaces adorned Egypt’s pharaohs thousands of years ago and were entombed with them as prized possessions to be used in the afterlife. Ancient Roman signet rings with carved garnets were used to stamp the wax that secured important documents. Clergy and nobility in the Middle Ages (475–1450 C.E.) also favored red garnet. The availability of this red gem increased with the discovery of deposits in central Europe around 1500. Known as “Bohemian garnets,” this source became the nucleus of a regional jewelry industry that reached its peak in the late 1800s.

Rubellite and pink tourmaline were favorite gems of the Chinese Dowager Empress Tz’u Hsi in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The majority of pink to red tourmaline mined in San Diego County’s famed tourmaline mines (Tourmaline Queen, Tourmaline King, Stewart, Pala Chief and Himalaya) during that period was shipped to China. Much of the material was carved into snuff bottles and other objets d’art, but the finest quality was set in jewelry.

Hot Red Gems

The hot, dry, high desert of eastern Oregon is home to Ponderosa, Dust Devil and Sunstone Butte mines – the primary sources of sunstone. According to Native American legend, the blood of a great warrior – wounded by an arrow – dropped onto pieces of Oregon sunstone. The blood carried his warrior spirit into the stones, coloring them with shades of red and giving them sacred power. The Oregon mines produce enough material to supply mass marketers as well as carvers and high-end jewelry designers.

Sunstone often exhibits aventurescence, a sparkly, metallic-looking luster caused by flat, reflective inclusions, sometimes called “schiller” by sunstone fanciers. Sunstone can be a variety of either microcline or oligoclase feldspar with an orange/brown background color. The color in Oregon sunstones comes from copper platelets that give it flash and sparkle.

Fire opal is a transparent to translucent opal with a background color that has smoldering hues of yellow to orange to red (some colorless fire opal is also found). Mexico is the primary source of fire opal, and material found there generally exhibits a strong play of color, though on rare occasions, no play of color. Smaller amounts of fire opal are produced in Australia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Honduras, Guatemala, Nevada and Oregon.

Rare Red Gems

Sweet Home Mine in Alma, Colorado, discovered in 1873 for its silver, produced the world’s finest rhodochrosite. The mine closed in 1967 after moderate success, but reopened from 1991 to 2005, during which it produced an estimated $100 million in rhodochrosite specimens. These gems are housed in several prominent mineral museums and private collections around the world. The largest known rhodochrosite crystal, the Alma King, is on display in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science and the Alma Queen is displayed in the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

Red beryl, also known as bixbite, is a North American gemstone found only in the Wah Wah Mountains of central western Utah. Most cut specimens are less than one carat. Since it is no longer mined, it has become rare, historical material.

Rhodonite is found in the sultry region of Minas Gerais, Brazil and Australia, Peru, Russia and the United States. Transparent rhodonite crystals are rare and seldom larger than one gram, but their hardness makes them excellent cut gemstones. The name rhodonite is derived from the Greek rhodon meaning rose.

Taaffeite (pronounced tar-fite) is named after Richard Taaffe, who found the gem in 1945 in a jewelry shop in Dublin, Ireland. It is the only gemstone to have been identified from a cut and polished specimen. Prior to Taaffe’s discovery, most pieces were misidentified as spinel due to their similar crystal form. It is one of the rarest gemstone minerals in the world.

The Moussaieff Red, originally named the Red Shield, is the ultimate in collectible red gemstones. It is an internally flawless, breathtaking 5.11 ct Fancy red natural color diamond. Discovered in the 1990s by a farmer in Brazil and cut from a 13.90-carat rough by the William Goldberg Diamond Corp., the rare red diamond was displayed in 2003 as part of the Smithsonian Institution’s “The Splendor of Diamonds” exhibit.

Although these red gemstones are often associated with the heat of summer, our passion and desire for them knows no season.

Sharon Bohannon, a media editor who researches, catalogs and documents photos, is a GIA GG and GIA AJP. She works in the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center.

.jpg)