Rare Books Project Puts Gem and Jewelry History Within Reach

November 28, 2016

The feeling of responsibility washing over Sarah Ostrye as she carefully turned the book’s pages was “nerve-wracking,” she admits.

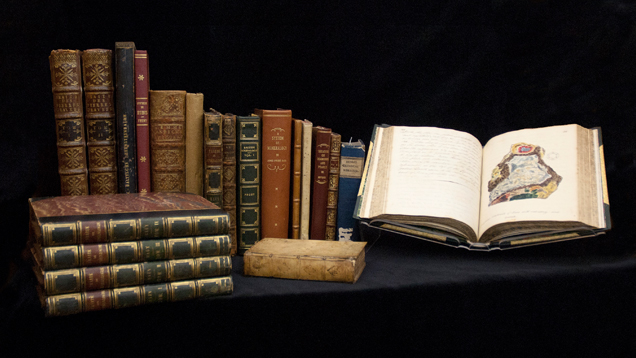

Then again, the manuscript in her hands was no ordinary book, but a 516-year-old copy of Pliny’s “Natural History” – the oldest in GIA’s 64,000-volume collection.

Ostrye, a research librarian and digital archivist for GIA’s Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center, is helping lead the Institute’s multi-year effort to bring thousands of the rarest, most venerated books in gemology, mineralogy and jewelry from the shelves of the library’s Cartier Rare Book Repository and Archives into easy reach of the global community.

To date, more than 200 historically significant books housed in the library have been digitized and made available for free through the nonprofit digital library Internet Archive. The public is responding: since the project was unveiled in July 2015, there has been a steady increase in monthly book views – from 378 views in July 2015 to 1,922 in September 2016.

That’s encouraging news for Dona Dirlam, director of the GIA library and architect of the digitization project.

“We can better serve the public trust by providing these resources,” she says. “The current and future state of gemology and the jewelry industry relies on having in-depth knowledge of our history – it’s the foundation for understanding the science and business of our industry.”

Access for All

What the project aims to do, in essence, is to make it as easy to enjoy an 1817 copy of Sowerby’s “British Mineralogy” with your morning coffee as it is to pick up a newspaper. What once required an appointment and a trip to the Institute’s Carlsbad, California world headquarters now takes a few clicks of the mouse.

Dirlam has spent nearly three decades planning how to expand the reach of the library’s collection, which represents 85 years’ worth of curation on the part of GIA librarians. (The collection’s size increased exponentially when the Institute acquired the John and Marjorie Sinkankas Gemological Library in 1988.)

“Once we had the Sinkankas collection, we began to think about how to provide greater access to it, and to GIA’s existing rare book collection, beyond the physical walls of the library. And one of John Sinkankas’ key desires was to enable as many people as possible access to his life’s work,” Dirlam says. “Because of advances in technology, this project is opening up the reach of this library and providing access to a global audience.”

Dirlam and her team, including library manager Paula Rucinski, consulted with multiple digitization experts through the years, from geoscience librarians to staff at Los Angeles’ Getty Conservation Center. Plans finally crystallized in late 2014 and GIA’s executive team gave its stamp of approval for resources – including the purchase of specialized equipment, and the hiring of Ostrye – in December 2014.

GIA librarians began to reach out to scientists and jewelry industry leaders for recommendations on which books in the library’s collection should be the highest priority for digitization. They added the rarest titles, and only those that were out of copyright.

In addition to Pliny’s encyclopedia – a work that was the foundation of all science until the Renaissance, and one of the largest single works from the Roman Empire to have survived – other early digitized titles include an 1801 copy of Renée Just Haüy’s “Treatise of Mineralogy” and Bishop Marbode’s 1511 treatise, “Book of Precious Stones.” Marbode’s work is the earliest lapidary (book on gemstones) from the Middle Ages, and the first of his works printed on a Gutenberg movable metal type press.

An especially rare, 1925-26 catalog of Russia’s Romanov dynasty’s regalia and crown jewels was the 200th book to be digitized, and gave the public its first look at the 406-piece collection.

The digitization project also ensures that these rare, delicate books are safeguarded for all time.

“We take every precaution to carefully preserve and secure this collection,” Dirlam says. “The Sinkankas Library and other rare books are housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room. If a natural disaster, such as a flood or fire, occurred and the books were damaged, however, we have the digital files that capture every word, photo and illustration. These books tell the story of gems and jewels and will be accessible for generations to come.”

A Painstaking Process

The digitizing process is a delicate one, full of potential complications for the technicians – including Ostrye and research librarian Augustus Pritchett – who are charged with creating digital files from often-challenging sources.

“Sometimes the text is very close to the gutter of the book, or there is fragile binding, delicate tissue paper overlays, or foldouts that may not fit under the glass platen,” says Ostrye. “Those require extra time and attention.”

The pair takes turns working in a secure room near the Cartier Rare Book Repository and Archives. The room houses a high-tech digitizing machine (Digital Transitions’ BC100 Book Capture system), that makes it possible to gently cradle the books instead of forcing them into a flat, spine-damaging position. Technicians turn each page manually to avoid skipping or tearing them, and capture high-resolution images that they edit and convert to TIFF files. Post-processing software even enables them to create searchable PDFs and e-books regardless of alphabet – including Roman, Cyrillic, Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

Visitors to the site are downloading more and more of the books every month, and Ostrye says it’s helping the library track trends in research.

“Based on which books are viewed the most, we can get an idea of which topics are most popular,” says Ostrye. “Many of our most-viewed books deal with the history of gemstones and jewelry design.”

Dirlam, who says the library will also begin to increase the availability of e-books and e-catalogs, notes that the public is welcome to submit recommendations for books to digitize. It’s one more way the library can engage the trade and public in the project, which she sees as imperative to ensuring the public trust in gems and jewelry.

“It is mission-critical that we preserve the important books, documents and other materials of the global gem and jewelry industry by digitizing them,” she says. “As Marjorie Sinkankas said, ‘We are only caretakers for a short time.’ It is our mandate to see that these materials are cherished and available for generations in the future.”

Jaime Kautsky, a contributing writer, is a GIA Diamonds Graduate and GIA Accredited Jewelry Professional and was an associate editor of The Loupe magazine.