A ‘Game-Changing’ Quality Assurance System for Jewelry Workmanship

September 6, 2017

A woman walks out of a big-city, high-end jewelry store. She and her husband have just made a remarkable purchase: a platinum ring featuring a 22-carat (ct), GIA-graded diamond center stone.

She proceeds across town, often admiring the sparkle on her finger, as she continues with her day.

A few hours later, she claps along with fellow patrons at a charity auction and her gaze falls again to the ring. She is shocked to see that the beautiful diamond is gone.

“One minor blow pushed that huge diamond out,” says Mark Mann, GIA’s senior director of global Jewelry Manufacturing Arts (JMA).

Mann served as an expert witness when this scenario – unfortunately, a real case – unfolded and went to court more than three decades ago. He says the ring made it to the sales floor despite “serious errors in design, engineering and workmanship” that left it primed for failure.

Cases of jewelry failure – lost stones, broken prongs, inconsistent sizing and distorted shapes – have been “an ongoing issue for the trade,” Mann says. The cringe-inducing “real-life consequences” include inconsistent quality, lost sales and damaged reputations, and can affect everyone from the largest jewelry manufacturers to the smallest brick-and-mortar retail shop.

Mann stresses that, for consumers, it doesn’t matter whether the missing stone is 22 carats or .02 carat – the emotional and mental effects are devastating.

“It’s disappointing at any price point,” he says. “And though jewelry failure is sometimes out of our hands, it’s often preventable.”

The Quality Assurance Benchmarks used in our JMA programs have proven to be powerful electronic, written and visual criterion that our QA team uses to provide students with real-time, appropriate industry feedback. It helps hone their knowledge on how to design, engineer and make quality jewelry.

Mann points to a couple of overriding factors that perpetuate the problem of jewelry failure.

“Consumers are trusting and have some preconceived notions about quality assurance,” he says. “When we go out and buy an automobile, the industry is so highly regulated that things are assumed. But even within a highly regulated industry, where quality absolutely has to be ensured, there are problems. There is no overarching, governing body that guides our industry as there is with other trades like automobile or equipment manufacturing, so of course issues come up.”

In addition to the lack of regulation, jewelers, manufacturers and retailers are rarely able to communicate clearly and consistently about workmanship.

“Quality assurance is not a new concept, but it’s carried out in a variety of company-specific methods, and terminology is different with every organization,” he says. “There is no common ‘language’ that ensures we can talk to each other and figure out how to rectify these problems or prevent them from happening in the first place.”

Identifying a Need

In the early 1950s, industry demand for more thorough diamond evaluation and education brought attention to the lack of a common “diamond language,” as GIA biographer William George Shuster describes in his 2003 book, “Legacy of Leadership: A History of the Gemological Institute of America.”

“At that time … diamond grading was chaotic and inconsistent because there were so many systems in use – and misuse,” Shuster says. “This left industry dialogue about a diamond’s features, and therefore its relative value, open to interpretation.”

The need for “terms and concepts acceptable and understandable to all” led GIA to develop the 4Cs of diamond quality and, eventually, the International Diamond Grading System™.

Today’s need for objective, consistent evaluation of jewelry workmanship and for a clear system of communication likewise catalyzed a GIA team, led by Mann and members of the JMA team, to create one.

Their systemized method of quality assurance for jewelry workmanship is called GIA Quality Assurance Benchmarks™, or GIA QABs™. In short, QABs are independently stated points of quality that Mann says are taken together to “provide an objective method for evaluating the quality of semi- or fully finished jewelry by comparing it against acknowledged criteria.”

While there are inherent differences in the way one grades a gemstone created by nature and the way one analyzes the “manmade” workmanship in a finished article of jewelry, Mann says, the concept of holding an item against objective criteria is the same.

And, just as GIA’s diamond grading system was “intended as a teaching mechanism, not a commercial system,” according to Shuster, GIA QAB concepts were taught in GIA classrooms well before their public release.

Developed for the Classroom, Refined at the Bench

Mann, whose 45 year career includes working within jewelry manufacturing, design and engineering in addition to GIA, knew when he was appointed to his current position that he and his team would want to rethink and improve the analysis of student workmanship.

“There was little or no information, visual or written, about defects in workmanship,” he says. “Instructors were doing their best to communicate certain details verbally, but they had no visual aids to support what they were trying to communicate.”

The JMA instructional and research and development teams, considering feedback from industry members, set about revising the review system for the daily work and bench tests of Graduate Jeweler (GJ) and Jewelry Design & Technology (JDT) students. They developed the QAB evaluation process and instituted it in 2013 for GJ students and in 2014 for JDT students.

“The Quality Assurance Benchmarks used in our JMA programs have proven to be powerful electronic, written and visual criterion that our QA team uses to provide students with real-time, appropriate industry feedback,” says Elizabeth Brehmer, GIA’s director of operations for Jewelry Manufacturing Arts. “It helps hone their knowledge on how to design, engineer and make quality jewelry.”

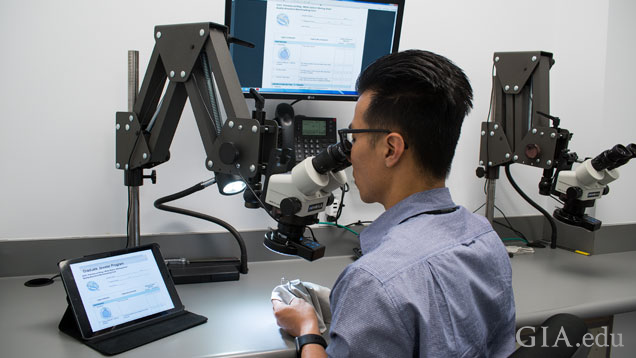

Students follow along with illustrated QAB analysis forms, which are broken into tasks and subtasks in each category, as they create and review their own jewelry pieces. Their work then moves on to the QA team, which reviews the piece of jewelry and checks a simple “Achieved” or “Not Achieved” box for each point of quality.

“It has been game-changing,” Brehmer says. “The methodology has made it possible for us to provide consistent, objective feedback to our students in an organized and structured manner. Our team can efficiently apply the criteria to multiple projects, in both the Jewelry Design & Technology and Graduate Jeweler programs, and instructors can coach students using these criteria to continually improve their understanding and application. Both students and instructors can immediately see areas that need improvement – and act on it.”

Mann agrees that instituting the QABs has worked “extremely well,” and alumni say it improved their classroom work.

“As a student, it was a way of keeping a focus on quality,” says Kenny Ray, director of gemstones for Fairfield, Ohio’s Quality Gold, Inc. and a graduate of GIA’s GJ and Graduate Gemologist programs. “It’s basically a checklist – follow it step by step, and when you’re finished with your project you can be pretty confident that your finished piece is complete.”

For Niki Grandics, an award-winning designer and bench jeweler from Southern California, utilizing GIA’s QAB system helped her plan her work.

“It encouraged me to be more proactive in problem-solving, because I already had those key criteria for that piece in mind as I was working on it,” she says.

And Amanda Chodosh, a GJ and JDT graduate who works as an apprentice jeweler for Shane Company in Colorado, felt relief – QABs meant there was no room for interpretation.

“After being an art major in my undergrad program, where everything was subjective and hyper-criticized, GIA’s QAB system was nice to adapt to because there was no guessing involved and everyone was assessed by the same standards,” she says. “I knew exactly what was expected of me. There were no hidden secrets or reading between the lines – it was very cut and dry, and you couldn’t cut corners. It’s either, ‘it achieved this,’ or ‘it did not achieve this.’”

In addition to improved efficiency, objectivity and thoroughness for students, classroom administrators found the QAB analysis sheets – permanent records of student work – to be helpful tools for data collection and tracking.

“I can look at forms and bring up student histories and formulate an opinion based on that data,” says Mann. “We can also use it on a bench test. If I look at data from the student sheets and discover that everyone is making the same mistakes or there are tool marks left all over the pieces, I can say, ‘It’s too late in the program for this stuff, what’s the discrepancy?’”

That makes it possible for administrators and instructors to see where improvements can be made – whether instruction should be adjusted, or whether there are areas of curriculum or hands-on training that need more work.

Real-Life Quality Analysis That’s Thorough, Efficient, Repeatable

Graduates have found GIA QABs indispensable for professional work.

Grandics, who is the owner, designer and bench jeweler of ENJI Studio Jewelry, is building an ethically focused brand using the QAB system she learned as a GJ student.

“For me, it means fewer surprises and fewer instances of taking things back for reworking or cleaning before a piece of jewelry goes out the door,” she says. “The working mindset that comes with these objective criteria helps me work more efficiently, but I see even more use for this as my business grows. When we expand our manufacturing in the future and hire more jewelers, using this system can help ensure a consistent quality standard, and that everyone is on the same page.”

“It can also help track performance and training. If some things are consistently an issue,” she adds, “you can respond to it much faster if you know about it before pieces go to the customer – rather than when they’re getting returned. It even makes training new hires easier when they know ahead of time what your standards are.”

Chodosh finds that the bench work she performs – stone setting and polishing, resizing rings, making repairs – on behalf of a national retailer is enhanced by her experience with systemized quality analysis.

“My position is not about my personal opinion; my job is to critically analyze a piece of jewelry for the company’s expectations and standards,” she says. “GIA’s QAB system is a practical, technical way to review a piece of jewelry so that it meets company requirements. I think it’s a healthy way to eliminate subjective opinions and creates structure and consistency throughout a company, brand or product.”

Ray says that employing the QABs helps him stay focused when the technicalities of quality assurance run up against the realities of busy, fragmented days.

“I’m able to follow the same routine any time I’m performing quality assurance, or training someone in it,” he says. “Days can become hectic, and the QABs can get me back on track after I’ve been sidetracked. I can pick up where I left off and be confident that nothing was left undone.”

Going ‘Beyond the Classroom’

Mann says that as the QABs were developed, the GIA team quickly recognized the ways the system could “go beyond the classroom” and benefit the industry.

“The same thing that the QABs bring to a classroom would help with quality assurance in a factory,” he explains. “Take the largest factory in Hong Kong, for example – the QAB data would allow you to track an individual’s workmanship. If you’re seeing the same department making the same error, you have it there in black and white. You can take preemptive measures to improve the supervisory situation, or hire someone to come in and train the skill where the problem lies.”

As the team began to understand the potential industry-wide benefits of the QABs, they decided to create a home for them on GIA’s website, where they would be accessible to the public. They began publishing the QABs periodically in 2016, and while they are currently available exclusively for platinum jewelry, QABs for other metals are planned for the future.

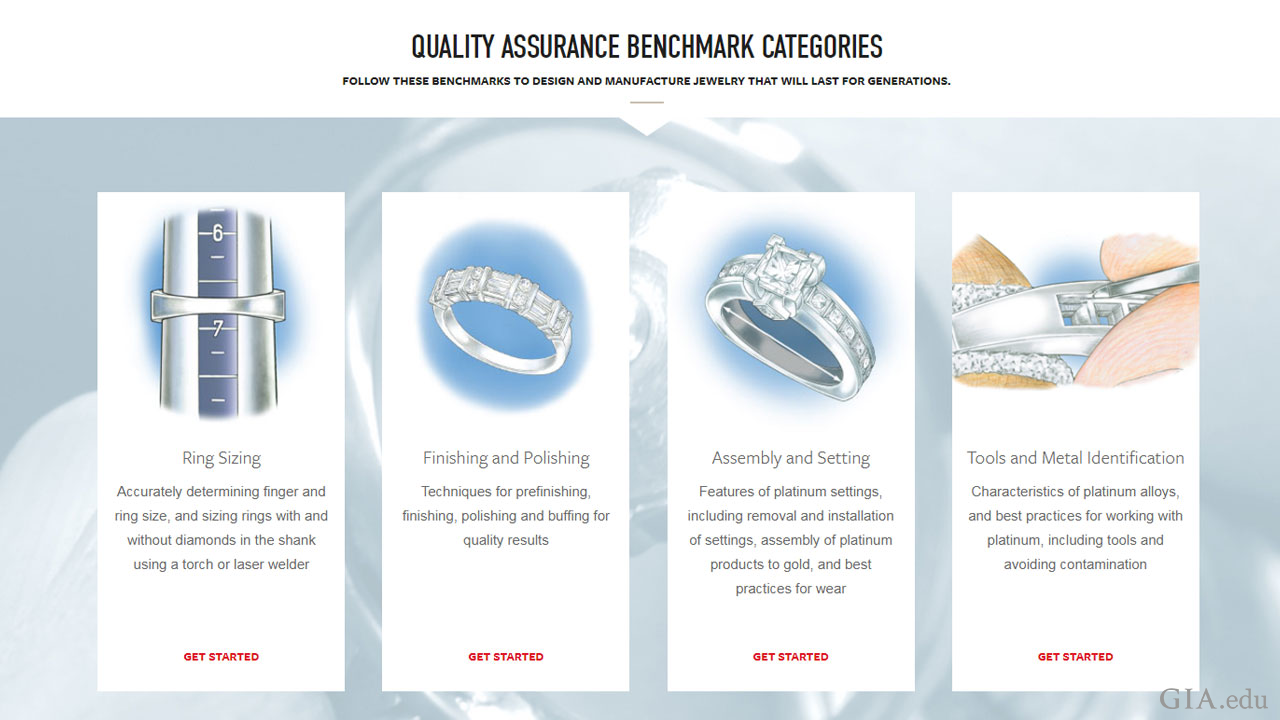

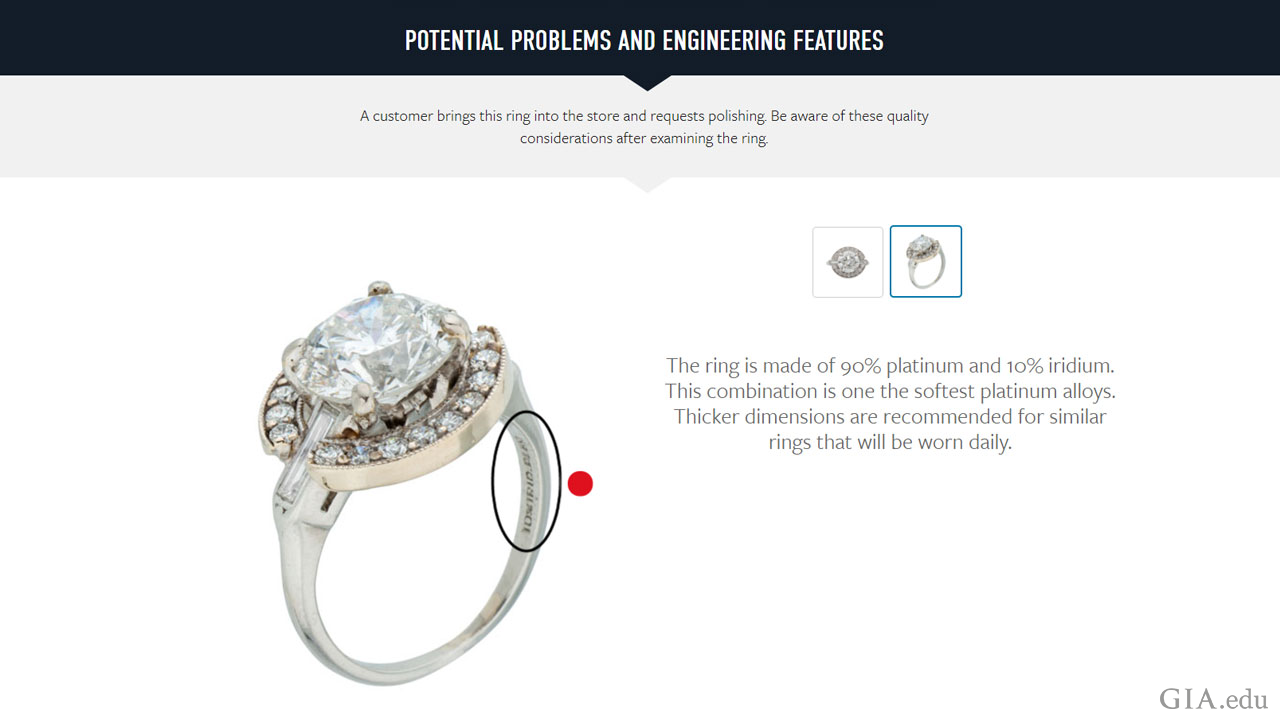

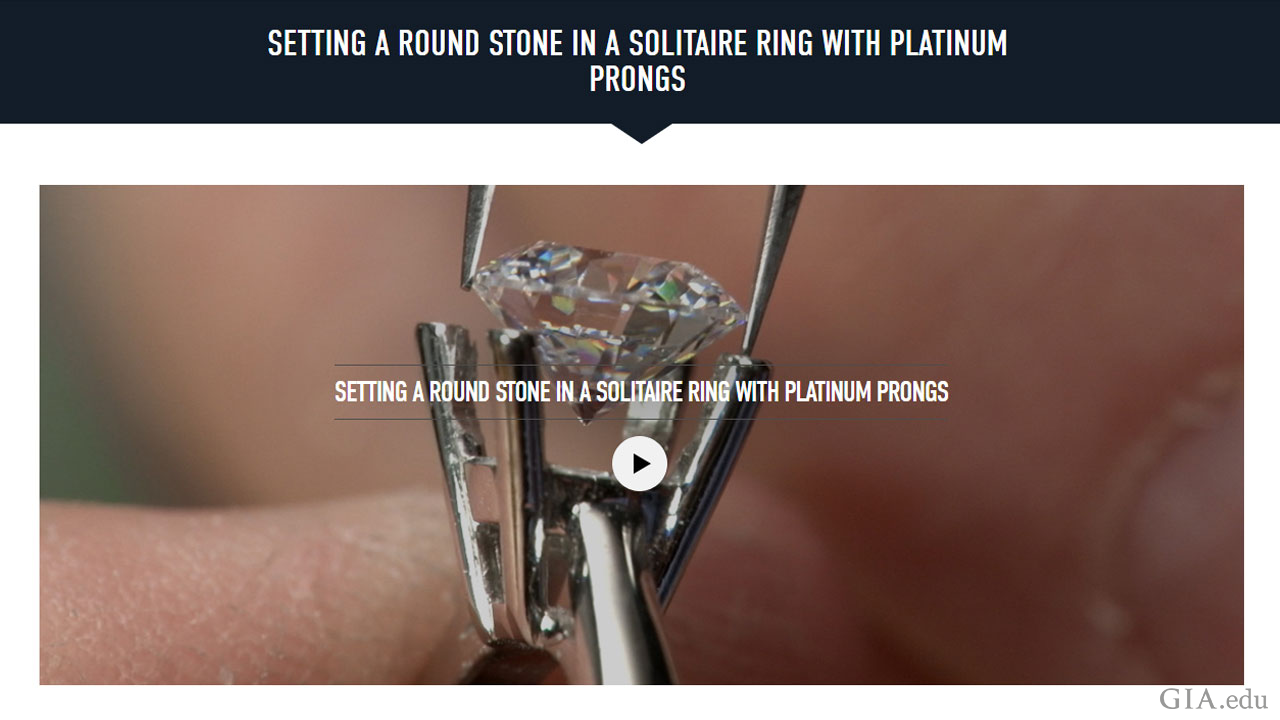

The QABs are presented online as interactive learning modules organized into one of four categories: Ring Sizing; Finishing and Polishing; Assembling and Setting; and Tools and Metal Identification. Each category features details on several topics, such as setting a princess-cut center stone in a platinum mounting, refinishing techniques for worn platinum jewelry and identifying/characterizing platinum alloys.

Each module includes benchmarks for specific situations, descriptions of possible problem areas or engineering features, and detailed artist renderings and photos of real jewelry. Many feature brief videos with demonstrations of manufacturing techniques, and red and blue beacons enable users to move through each module and track their progress.

In the year since GIA began publishing the QAB modules online, the pages have drawn nearly 30,000 views. For Bev Hori, GIA’s senior vice president of education and chief learning officer, those numbers signal high interest among trade members to embrace methods that can improve jewelry manufacturing and workmanship, and the industry as a whole.

“We felt that it was important to share what was working so well in GIA classrooms,” Hori says. “GIA’s Quality Assurance Benchmarks have been an effective tool for our students and instructors, and providing them as a resource is a way to share that knowledge and experience with the trade. It is also a meaningful way we can help fulfill the Institute’s mission of ensuring the public trust in gems and jewelry.”

Brehmer believes that the impact of systemizing quality assurance will be far-reaching.

“Everyone benefits from a well-made piece of jewelry: the manufacturer, the retailer, the jeweler and the consumer,” she says. “It takes no more time to make a well-engineered jewelry item than it does a poorly engineered one. The key is valuing – and knowing – how to make quality jewelry that will last.”

Jaime Kautsky, a contributing writer, is a GIA Diamonds Graduate and GIA AJP and was an associate editor of The Loupe magazine.