Museum, Lab Collaborate with Students on Design Project

Artists are often inspired by the beauty of the materials they use. A sculptor may sense form in a block of stone; a painter might sense the image in the texture of a canvas. In the same way artists transform canvas and stone, jewelry designers manipulate gems and metals into works of art, taking inspiration from the raw material. That inspiration, however, strikes each artist or designer differently.

GIA’s museum and laboratory staff recently collaborated with the Institute’s first Jewelry Design & Technology (JDT) class to encourage students to find inspiration in gems. The effort tapped into the museum’s wealth of history and knowledge and the analytical and research tools of the lab.

“JDT students often have the opportunity to see beautiful gems and jewelry from GIA’s museum, but have never had the chance to create their own designs with gems from the collection,” said McKenzie Santimer, GIA museum exhibit developer. Terri Ottaway, GIA museum curator, and Santimer challenged students to design rings featuring five tourmalines from the museum.

The tourmalines, ranging in size from eight to 11 carats, span the color spectrum. Four were originally owned by Edward J. Gübelin, a pioneer in the world of gemology who amassed one of the most extensive personal gem collections in the world, which was acquired by GIA for the museum in 2005.

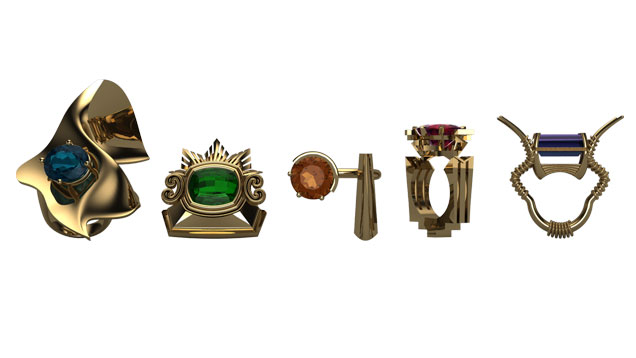

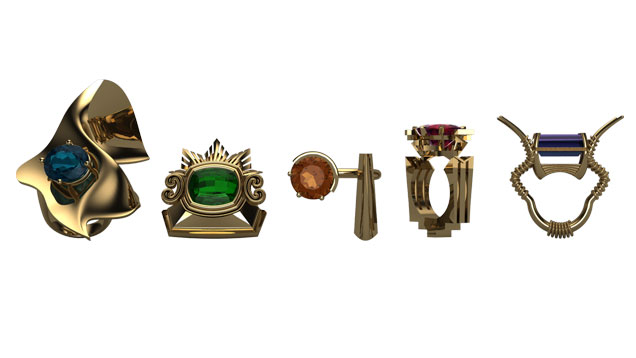

The project gave students the freedom to explore their own design style. The GIA museum staff, as clients for these designers, gave the students careful requirements. Each of the five tourmalines had to be incorporated into a size seven, yellow gold ring with up to one carat of side diamonds to enhance the designs. To encourage the students to find inspiration in the beauty of each stone, Ottaway and Santimer described the localities where each of the tourmalines were mined in Brazil (8.15 carat cushion-shaped red and 11.96 carat cushion-shaped green), Namibia (9.89 carat emerald-cut bi-colored red and blue), Nigeria (9.4 carat oval-shaped blue) and Mozambique (9.15 carat round orange).

Hannah Becker, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, embraced the opportunity to design a collection that would highlight the “big and flashy” tourmalines. She relished the chance to work through her own ideas to create pieces that match her style. When she learned the green tourmaline came from Minas Gerais, a town in Brazil known for baroque-style churches, she designed a ring reminiscent of the architecture she learned about while studying art history.

“Everyone’s projects were really different and demonstrated what we’re interested in,” she said. “It was fun to see how everybody tackled each stone.”

Josh White, of San Francisco, California, instantly found his inspiration when he saw the tourmalines. “I knew I wanted to design something elegant,” he said. His designs featured traditional techniques such as prong and bezel settings.

This CAD rendering, designed by Josh White, illustrates prong and bezel settings. ©GIA

The GIA laboratory used 3-D scanning technology to create a representation of each tourmaline, called a stereo lithography file (STL file). The file was then imported into CAD (computer-aided design) systems so the students could create renderings of their designs that matched exact specifications of the stones.

"Technology from the GIA lab, like the 3-D scanning machine, helps ensure students have the latest tools used in the jewelry industry," said Mark Maxwell, GIA's Jewelry Manufacturing Arts manager. “This is how our students benefit from the work done in our lab.”

White learned first-hand how important this technology is when he was asked recently during a job interview if he had experience with 3-D scanning. He was able to give specific examples, including his designs from this project.

“Cookie-cutter stones don’t exist in the real world,” he said. If you plan to work in custom jewelry, you need to know how to design using 3-D scanning, he added.

Students also made rapid prototypes of their designs using the 3-D rendering and CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) tools. The prototypes are an exact representation of their design, from the intricate aesthetic details to dimensions that precisely match the tourmalines. Maxwell demonstrated the perfect fit by placing one of the tourmalines into the prongs of the plastic prototype designed for it.

“Our goal is to create real-life, real-world experiences for the students,” he said. “This project is just one of many that prepares them for situations they’ll likely encounter in the jewelry industry.”

This plastic prototype was made using CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) tools after Alyssa Brownell created a CAD rendering (inset) of her design. ©GIA

Students presented their projects to fellow classmates, instructors and Ottaway and Santimer. The instructors gave feedback on the practical aspects of their designs; Ottaway and Santimer responded from an artistic standpoint, discussing how the rings highlighted the stones and the quality of the design.

Santimer enjoyed working with students on the project because she said it let them explore jewelry as an art.

“Some students designed avant-garde pieces that would be difficult to wear, but are meant for display in the museum,” Santimer said. “If it’s art, you can break the rules.”

In the end, for Becker, it was all about the gems. “The museum is such an invaluable resource because of the beautiful and historic gems they have,” she said. “With this project the stones dictated our designs.”

Talk about inspiration.

Hannah Becker found inspiration for her designs from the localities where the tourmalines were mined. ©GIA

About the Author

Kristin A. Aldridge, a writer at GIA, is a graduate of GIA’s Pearls and Accredited Jewelry Professional programs.