Gem Cutting Styles - Definitions

August 9, 2018

Part 2 of 5 in the series: Value Factors, Design, and Cut Quality of Colored Gemstones (Non-Diamond)

Originally published in GemGuide in 2016, this comprehensive series examines the quality factors that influence the value of colored gemstones, with a specific emphasis on the role cut quality plays in determining the value of faceted gems. GIA researcher and cut expert, Al Gilbertson, examines the elements of cutting, investigates the choices and tradeoffs a cutter makes and why, and provides guidelines for assessing various aspects of cut quality for colored gemstones.

This web version of the original series is divided into five separate articles and reflects minor stylistic edits to the original.

In Part 1 of this series we reviewed the seven major factors that affect the price of a colored gemstone: color, uniformity of color, country of origin, size, clarity, shape, and quality of cutting. We now need to define aspects of cutting styles to establish some common language, with a focus on basic faceting styles, and a short discussion on cabochons and beads.

A note on the wireframes or depictions of facet arrangements used throughout: These were created from scans of real gems to illustrate aspects of gem cutting. Face-up patterns (such as Fig. 2-14) were made using the program DiamCalc; adjustments were made to the refractive index to represent the gem material being demonstrated. DiamCalc cannot show double refraction.

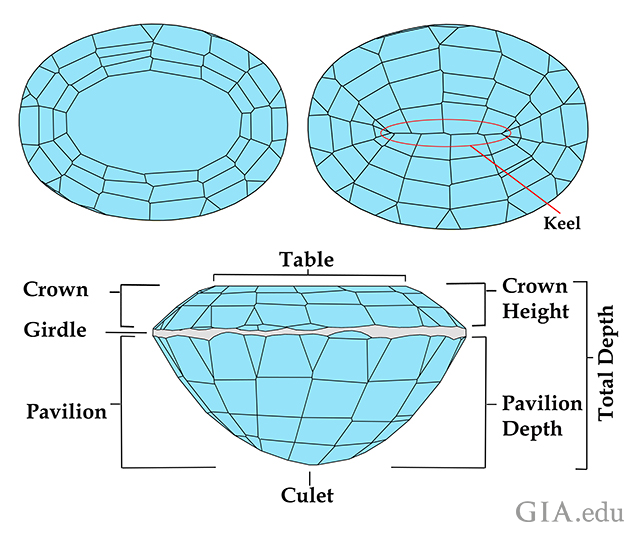

Parts of a Faceted Gem

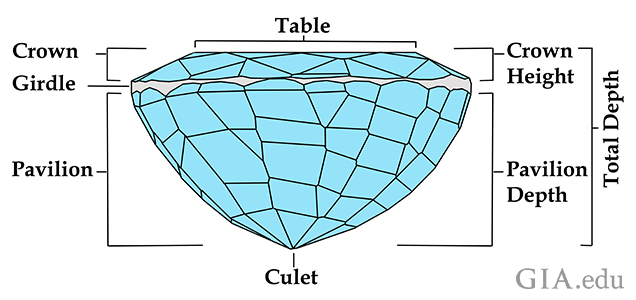

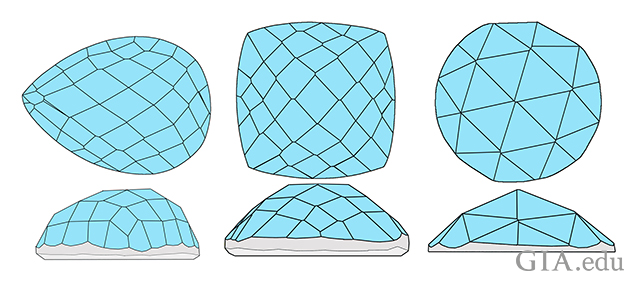

Generally speaking, most faceted gems have common features, like a crown, girdle, and pavilion. However, many gems cut in certain parts of the world have such irregular pavilion facets (see Fig. 2-01) that the facets themselves defy normal naming conventions.

Usually gems are fashioned so that the observer is looking through the table, the flat top facet on the crown (top portion) of the gem, to see how light has been collected and returned back to them to view. The girdle is the outer edge of the gem, where metal grips the stone to hold it in place in jewelry or art. The pavilion is the bottom portion of the gem. If the pavilion facets come to a point at the bottom, that point is called a culet. Sometimes there is a small facet at the culet that is parallel to the table. This is called a culet facet.

The total depth of the gem is the total thickness of the gem from the table to the culet. A gemstone's crown height (listed as a percentage of the diameter) can vary from deep to shallow, depending on the cutting style. Pavilion depth (expressed as a percentage of the diameter) can also vary. If a pavilion depth is too shallow, you will see through the gem, called windowing, and if it is too deep, the gem will appear dark overall.

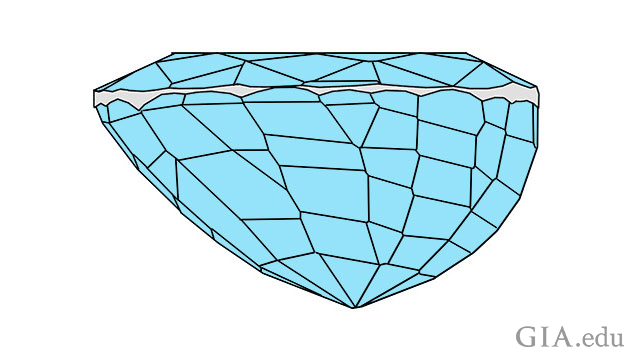

A lot of what is referred to as “native cut” (discussed in detail below) can be exemplified by Figures 2-01 and 2-02. The facets are often very irregular on the pavilion. The crown can be somewhat more orderly, but can be as irregular as the pavilion. The culet can be considerably off center in native-cut gems (see Fig. 2-02). These gems were cut intentionally with the culet skewed to one side. Re-cutting these to improve cut quality will usually sacrifice the color, substantially decreasing its value.

Brilliant Styles and Facet Names

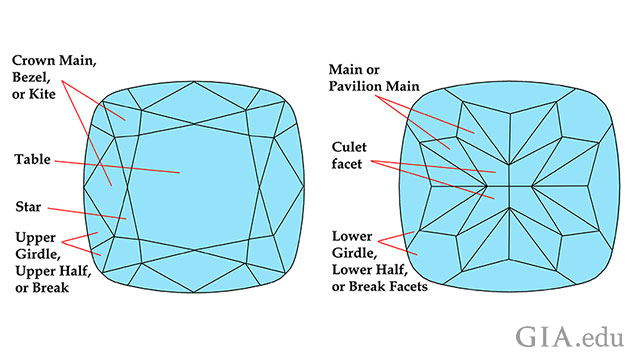

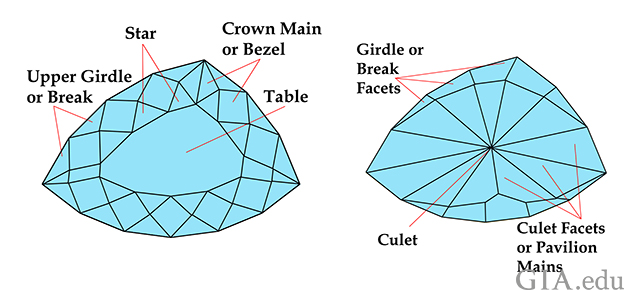

There are two important segments of the trade that sell colored gemstones—those whose focus is diamond and those whose focus is colored gemstones—and sometimes these two groups have different names for certain parts of the gem. Listed on Figure 2-03 are the most common names used for those facets.

The table is often the largest central facet on the crown. Crown mains (bezels in the diamond trade) are usually kite shaped, and refer to a position between the stars (triangular facets bordering the table) and the break or upper girdle facets (bordering the girdle). Crown mains usually touch the edge of the table and the edge of the girdle.

Colored stone cutters refer to pavilion facets that touch the culet area as culet facets, even though the facets are not parallel to the table (this type of labeling is common in diagrams generated by software used by colored gem faceters called GemCad). In this diagram (see Fig. 2-03), the kite-shaped culet facets may also be referred to as kite facets. When there is more than one row of either triangular or kite-shaped facets between the lower girdle facets and the culet (or culet facets), the facets of the intermediate rows are called mains or pavilion mains. Often adding confusion, there can be several rows of facets in this region and all of them can be referred to as mains. The names lower girdle or lower half facet are used in the diamond trade to describe facets at the girdle on the pavilion side, but colored stone cutters usually refer to these as break facets.

As shapes become less symmetrical, facet arrangements become less standardized. In Figure 2-04 the faceting style is still brilliant, but there can be some confusion on what to call some of the pavilion facets, since they don’t assume the common shapes for brilliant styles.

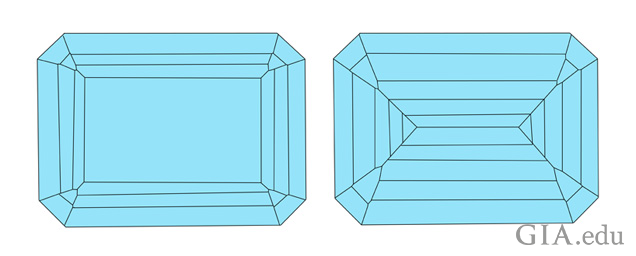

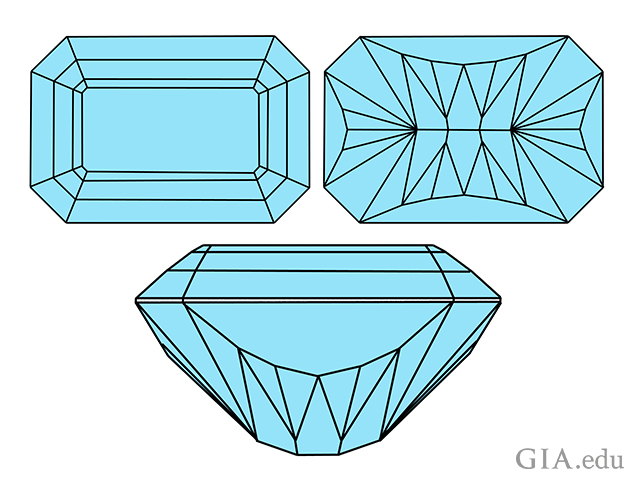

Step Cut Styles

Many facet arrangements consist primarily of step cuts, the most classic being the emerald cut (see Fig. 2-05). Any shape can be cut with step cuts. Figure 2-06 illustrates an oval step cut. Note that the facets don’t meet carefully, and many are not parallel. This is usually the case in most commercially cut gems. The higher the precision of cutting, the better those facets will meet. Note that there is a line that forms along the bottom of this facet arrangement, not a single point for a culet. While the bottom is still referred to as a culet, this line is often called a keel or keel line. Step cuts usually have keels.

Step-cut facets are four-sided, with the upper and lower edges being nearly parallel. For crown facets, the upper edge is parallel (or nearly so) to the table edge and the bottom edge is parallel (or nearly so) to the girdle. In most commercial cutting there are triangular facets that are left over from where the steps don’t meet well. Sometimes these can be five-sided (like the corners on the crown of the emerald cut; see Fig. 2-05).

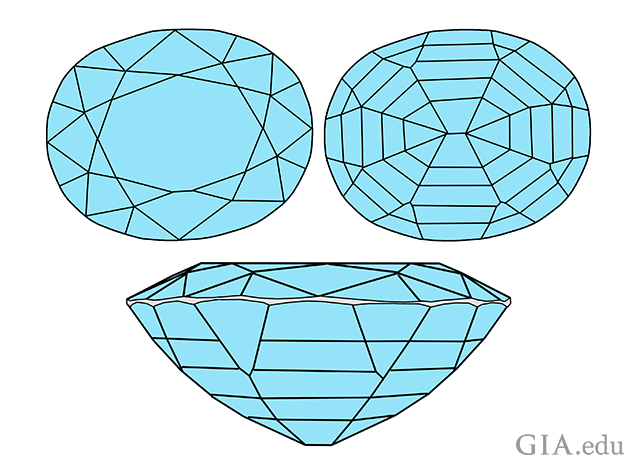

Mixed Cut Styles

Mixed cut means that the cutter used both brilliant and step-cut styles in the facet arrangement. Ovals and cushions are often cut with step-cut pavilions, but brilliant style crowns (see Fig. 2-07). This breaks up the light into yet a different pattern. Remember that uniformity of color is important for the value of a colored gem. Mixing the styles of cutting will also assist in evening out the color and minimizes the effect of a small window at the culet.

For more uncommon cuts such as the Barion cut (see Fig. 2-08), facet names can vary with different cutters.

Rose Cut Styles

The rose cut features a flat bottom with a dome-shaped crown reaching an apex (see Fig. 2-09) formed by 3 facets or more. Rose cuts, so named because they resemble the shape of a rose bud, were originally cut in diamond in the 1500s. By the 1800s this cutting style had moved over to a few colored gems such as marcasite and garnet. Recently, it has found fashion in a number of other colored gems.

Non-faceted Cutting Styles

The non-faceted styles of gem cutting predate faceted styles, with the earliest form being either the bead or cabochon (or cab). A gemstone bead is fashioned in a variety of shapes and sizes, and is pierced for threading or stringing. The material can be transparent to opaque.

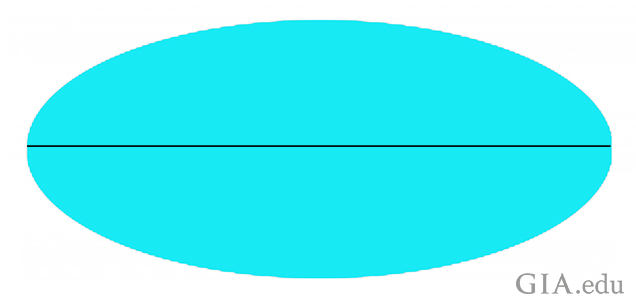

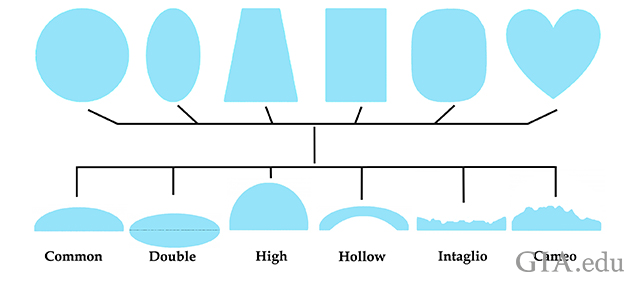

Cabochons: Simple and Double

The simple cab has a rounded top and flat bottom (see Fig. 2-10), and the double cab has both a rounded top and bottom (see Fig. 2-11). The usual traditional shape for cutting cabs has been an ellipse (oval). This is probably because the eye is less sensitive to small asymmetries in an ellipse, as opposed to a uniformly round shape, such as a circle. The elliptical shape, combined with the dome, is also attractive. More recently many shapes, including freeform, are used for cabs. The term ‘cabochon’ is often used to describe any gemstone shape that is not a bead, carved, or faceted.

Cabochons: Asterism and Chatoyancy

In the case of asteriated gems such as star rubies, and chatoyant gems such as cat's-eye chrysoberyl or tourmaline, a high domed oval or round cab cut is necessary to show the star or eye, which would not be visible in a faceted cut. For those better quality star or cat’s-eye gems that are often translucent to near-transparent, the quality of how the back has been finished will be more important. The back should be unpolished (see the first two gems of Fig. 2-12). Josh Hall (Vice President of Pala International, Inc.) points out that if the back is polished for a highly transparent gem, the star or cat’s-eye effects will appear diminished if not almost gone (the third gem of Fig. 2-12). For finer translucent and transparent gems with an eye or star that is not quite sharp, sometimes a coarser finish on the back will sharpen the line. The backs of star and cat’s-eye gems can sometimes be very deep, adding unnecessary weight.

Any outline can be cut in any of these cabochon variations (see Fig. 2-13). Early forms of cabs were sometimes carved (seals, scarabs, cameos, etc.), and today there are certain common variations of the cab: double, high, and hollow. Hollow gems can have one of two purposes: 1) They are used to deceive by putting colored glue behind a thin translucent wall of the gem to intensify a certain color; or 2) Exceptionally dark gems can have their apparent color lightened.

Cabochons: Cameos and Intaglios

Cameos and intaglios are the most common form of carved cabs today. Cameos are made by cutting away material; the design remains above the level of the base. With intaglios, the reverse of the cameo, a design is cut into the gem below the highest part of the surface. The most common subject matters were historic or religious figures, and frequently used materials have different colored layers (like banded agate) which can be revealed in forming or embellishing the image (the face will be one color, while the background is another color). Shell and agate are two of the most commonly used materials, but others include amber, coral, jet, and lava.

Carved gems can take any form, from freeform and geometric to carved flowers, animals, or mythical beasts and more recently modern carved gems can replicate a photo of a family member. In recent decades, the hand-carving of these types of gems has been modernized by ultrasonic machines. Gems with higher levels of intricacy cut by ultrasonic methods are not as valuable as those cut by hand.

Cabochons: Composite Gems

While most commonly seen in cabochon form, composite gemstones are also found with faceted gems when two or more gem materials are bonded to form a single gem. Common forms include opal doublets (two parts) and triplets (three parts). Sometimes faceted gems are cemented together with the intention to deceive; a natural gem material is used on the crown and glass or some synthetic is used on the pavilion. A colored cement layer can even change the apparent color. Intarsia is a composite art form of inlaying that fits pieces of gems together to form a picture or mosaic.

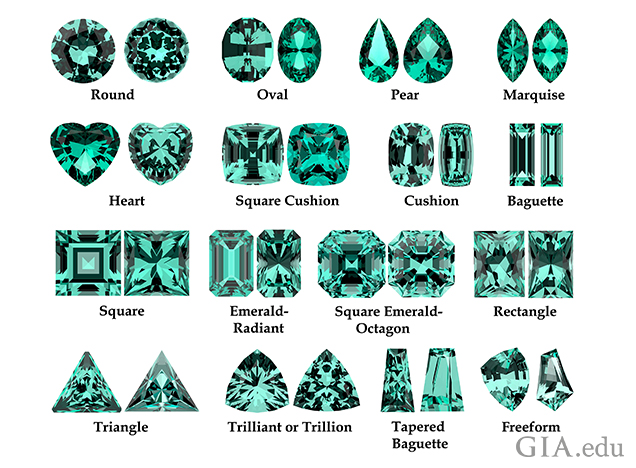

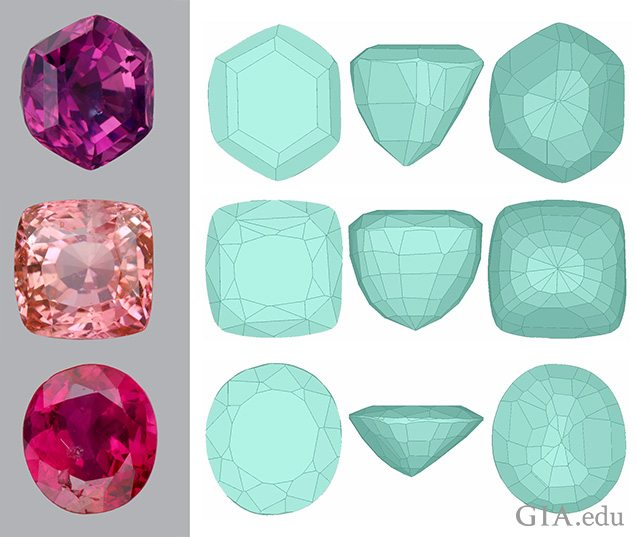

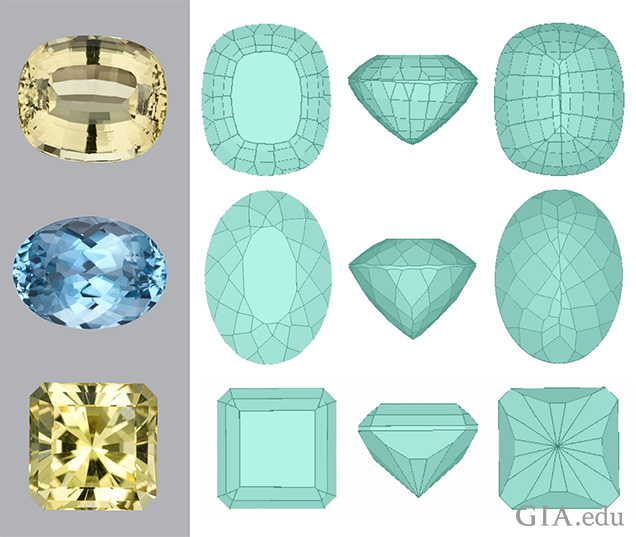

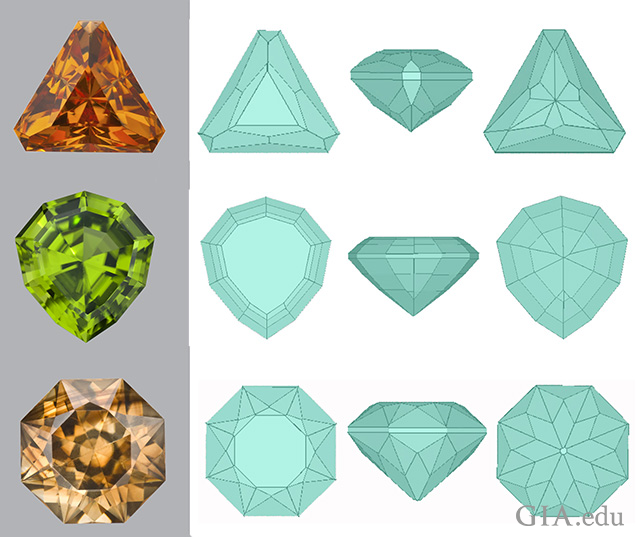

Shape and Sometimes Cutting Style

As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, “Colored Gemstone Value Factors,” the shape or outline of the gem and sometimes the cutting style are value factors. Certain shapes are in higher demand and make the gem more saleable. The outline of a gem can be a variety of shapes and with each there is an almost unlimited variety of facet arrangements. Figure 2-14 shows some of the most common shapes used in the trade, each with more than one facet arrangement. A few of these names can be confusing. Emerald can refer to the outline, or to a specific facet arrangement or cutting style with that outline. For instance, a radiant has a brilliant cutting style with an emerald outline. The square emerald (a debated moniker) is the same as an octagon. A triangle, trillion, and trilliant can have flat sides (sometimes with cut corners), or curved sides. Other outline shape names not shown include briolette, hexagonal, keystone, kite, lozenge, pentagon, rhomboid, s-curve, seven-sided, shield, and trapezoid.

Cut Quality Types

The sections above grouped and described prevalent cutting styles by the cut’s outline and facet arrangements (rose cut, emerald cut, cabochon, etc.). However, the overall quality of the cutting can also be grouped into broad categories and described. Note that naming these following quality types is more for convenience and is arbitrarily chosen by the author. There are exceptions as types blend into each other and they are not always easy to classify.

"Native-Cut" Gems

“Native cut” often indicates a cruder appearance, referring more to an almost outdated method of cutting and thus an assumed lack of accuracy. There are very few native-cut gems in the market today.

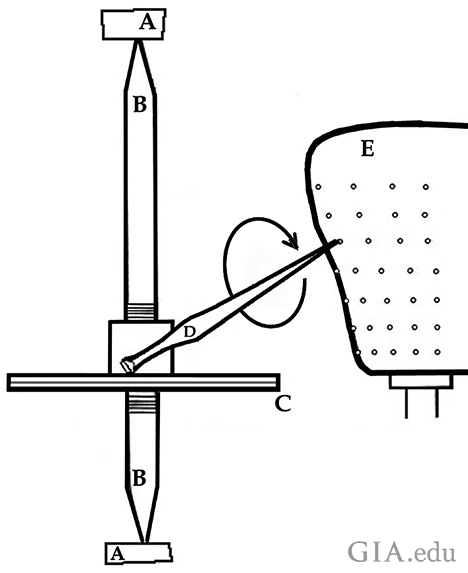

Native-cut gems are usually cut with jamb-peg machines (see Fig. 2-15). The rotating lap (C) provides the grinding and polishing surface. The wooden "dop" stick (D) to which the rough gem is cemented, holds the gem in position as flat facets are placed. The angle of each facet is controlled by placing the dop stick in a particular hole (E), but the faceter controls how much is cut away by the amount of pressure and time the gem stays in contact with the lap. The radial placement of the facets around the gem is done by lifting the dop away from the machine, slightly rotating and reinserting the dop in the same hole (for a certain row of facets) as each different facet is placed. This is doubly difficult since facets are first placed with a coarser grit on the lap, and then the process is repeated by polishing each facet on a polishing lap. There are many gems produced this way (see Fig. 2-16). Note that the outlines are often asymmetrical and facets are not well placed. Typically the crowns are cut more carefully with facets meeting fairly well, while the pavilions have extra facets, uneven rows, poor meeting of facets, and off-center culets.

Gems by jamb-peg are, as mentioned above, assumed to be a cruder type of cutting and assumptions are that they are poorly executed and less accurate. That is not always the case. In fact, the faceting arrangements that evolved through this method enhance and spread out the color very consistently (remember that uniformity of color is very important). There are cutting firms that excel at carefully placing facets in those old style arrangements by both the jamb-peg method and using modern faceting machines.

Commercial Cut Gems

“Commercial cut” includes many native cutting styles (facet arrangements), but the cutting quality is better (see Fig. 2-17). In particular the outlines are even and symmetrical, and there is much better facet symmetry. For this article, commercial refers only to a general quality of cutting, not to a general quality of the gem material. In cutting centers that used to be known for native-cut gems, a “master” may still preform the gem using the old cutting style standards, but then modern methods finish the gem. Obviously there is a range of quality for both native cut and commercial cut goods, and the border between the two is often unclear.

Designer Cut Gems

Just as the border between commercial cut and native cut gems is somewhat ambiguous, the border between commercial and designer cuts is also ambiguous. The scapolite gem, shown as the third design in Figure 2-17 above, could be viewed by many as a designer cut.

“Designer cuts” (also called “precision cuts”) are best described as gems where the designer creates a unique face-up pattern utilizing unusual facet arrangements while using traditional faceting methods (see Fig. 2-18). The goal of most designers is to create a crisp appearance with a unique face-up pattern, whether that is bright and sparkly or purposely windowed as part of the unique face-up pattern. There are many cutters within the US that cut for local jewelers as well as large-scale cutting firms (some are members of groups like the American Gem Trade Association) that have booths at trade shows.

Distinctions between designer and craftsman are better understood when compared to the auto industry. Designers design a new model of car, and skilled artisans or craftsmen make thousands of ‘clones’ of it in the factory. Here in the context of this article, “designer cut” distances itself from the many facet arrangements that have been traditionally produced to create new face-up appearances. But the comparison to auto industry breaks down here, because once a new design has been produced that is visually interesting, it gets reproduced by many, with the design often being shared with other cutters. Those who repeat these designs are perhaps better called artisans, and their gems can be referred to as designer cuts, since they break with more traditional facet arrangements and are more precisely cut. This may be why some choose to use the less confusing term “precision cut.”

Fantasy Cuts and Artistic Cutting

“Fantasy cuts and artistic cutting” includes both unusual outlines with standard faceting and standard outlines with concave faceting (see Fig. 2-19). Most of these designs have a unique arrangement of polished grooves on the pavilion that creates a dynamic outline. Polished grooves on the pavilion (or crown) help to create new patterns of light not possible with conventional faceting. Some artists have found ways to use odd rough, such as Glen Lehrer who uses shallow rough for his Torus Cut. This discussion (taken up again in part 5 of this series) is limited to faceted styles mentioned above and avoids those borderline areas (carved designs as well as “optical dishes” sometimes placed seemingly randomly on the reverse of a gem).

The term fantasy was derived from the German word phantasie, meaning fancy, and is an attempt to classify this style in conventional lapidary terms. One of the most significant artists for fantasy styles is Bernd Munsteiner, who introduced this style in the 1970s. Munsteiner focuses on what he calls "total reflection," seeming to, as one called it, "sculpt internal facets." Cutters of this style aim to create objects of beauty from gem materials. Since American and foreign factories and cutters are mass producing designer knock-offs of some of the most well-known designers using lower quality gemstones and less detailed workmanship, it is easy to find less expensive examples that are not well cut.

Summary

At this time, factories are producing gems whose qualities certainly mimic artistic and precision cutting, but careful examination of the cutting quality shows that they don’t have the precision or quality expected. With the advent of automatic cutting machines, we expect the quality of commercially cut gems to improve, blurring the lines between the quality ranges.

In this article we defined aspects of various gem cutting styles to establish some common language, with a focus on basic faceting styles. In doing so, we also began examining how a cutter’s choices can impact the final appearance (and value) of a colored gem.

In the next installments in this series, Parts 3 and 4 will dig deeper to explore many of the choices cutters make and why, as well as the factors used in the trade to assess relative value. Part 5 will discuss issues of craftsmanship. Together, the articles will provide a foundation for understanding cut quality and its value impact for a gem material.

UP NEXT: Part 3: "Darkness and Brightness” examines how cutting decisions can have a profound effect on a gemstone’s color quality.

Al Gilbertson is the Project Manager, Cut Research at the Gemological Institute of America Laboratory Carlsbad. Prior to joining GIA, Gilbertson served on the the American Gem Society (AGS) Cut Task Force, where he made significant contributions, including developing a patent which was acquired by AGS as the foundation of their ASET technology for cut grading. Hired by GIA in 2000, he became part of the research team that created the GIA cut grading system for round brilliant diamonds. Gilbertson is also the author of American Cut—The First 100 Years.

Thanks to Wayne Emery (The Gemcutter), Brooke Goedert (Sr. Research Data Specialist, GIA Carlsbad), Josh Hall (Vice President of Pala International, Inc.), Dalan Hargrave (Gemstarz), Richard Hughes (Lotus Gemology), Stephen Kotlowski (Uniquely K Custom Gems), Andy Lucas (Manager, Field Gemology-Education, Content Strategy-Gemology, GIA Carlsbad), and Nathan Renfro (Analytical Manager, Identification, GIA Carlsbad) for reviewing this article and providing valuable input.

Parts one and two of this series appeared in GemGuide, January/February 2016, Vol. 35, Issue 1; parts three and four in March/April 2016, Vol. 35, Issue 2; part five in May/June 2016, Vol. 35, Issue 3. Note that the article does not use the term faceted in the title. However, the major thrust of this series is faceted gems.

Gemworld International, Inc., 2640 Patriot Blvd, Suite 240, Glenview, IL 60026-8075, www.gemguide.com

© 2016 Gemworld International, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission granted for GIA to publish this at GIA.edu.