A Sunstone Odyssey, Part 3:

Sunstone Butte

October 20, 2013

CRYSTALS FROM A CINDER CONE

We’ve come out here on the last day of our quest for Oregon sunstone. It’s about a dozen miles or so away from Dust Devil. We’ve already met both owners, as they visited Don and Terry at their mine during our stay. We’ve heard about Sunstone Butte’s large, fabulous sunstones from the other miners and we’re very eager to see them for ourselves.

When we first arrive, Dave is away, helping recover a truck that a mining acquaintance rolled over on one of the nearby dirt roads.

The mine’s camp is a clutch of trailers halfway up the slope of a hill. Blue five-gallon buckets full of feldspar concentrate surround the end of one of the trailers. Another dog—a bigger one called Sheba—barks a welcome.

There’s a crunch of gravel as a truck pulls up. Dave is back after helping right the vehicle that rolled over: The driver is OK, but the truck is a wreck.

Pretty soon, we’re standing in a manmade crater under a pure blue sky—the main pit of the Sunstone Butte mine. “It’s a vent, a volcanic vent…much more cinder dome than lava flow,” Dave explains, telling us why his operation is unique compared to other mines in the Rabbit Basin. Rather than mining a relatively thin basalt flow, the operation is excavating the center of a miniature volcano—a cinder cone: “Our pit has four different, distinct layers in it…Geologists have been to all the sunstone mines…I’ve had three or four swing by and they’re in heaven…”

Dave points to the reddish brown rocks exposed in the pit wall and tells us, “The whole side of this hill is just full of sunstones.” He bends down and picks up a bright yellow feldspar from the ground. “The amount of crystal in this pit is just incredible…every rock, just about, has a crystal in it!”

Dave mines the core of the hill using a backhoe. He runs the ore through a grizzly—a metal grille—to remove rocks larger than eight inches, which he stores for a later crushing process. The ore smaller than eight inches runs through a small processing plant that removes the loose dirt. Next, they hand-screen the ore on four-by-eight-foot metal-topped tables. Dave and Tammy chose metal surfaces rather than conventional mesh because the rocks roll more easily across the top and the metal reflects the light back up through the feldspar crystals and makes them much easier to spot.

Dave estimates that changing to metal allowed them to recover sunstone at four times the previous rate. Dave does admit that it’s hard work. “Tammy sits here and she does most of the screening…She’ll do this for about eight hours a day.”

Two days of running ore through the grizzly and two days of running the processing plant provides enough material for both to screen for a month. “We’ve put a lot of work and effort into this mine…When we’re up here, we’re mining, pure and simple,” he tells us.

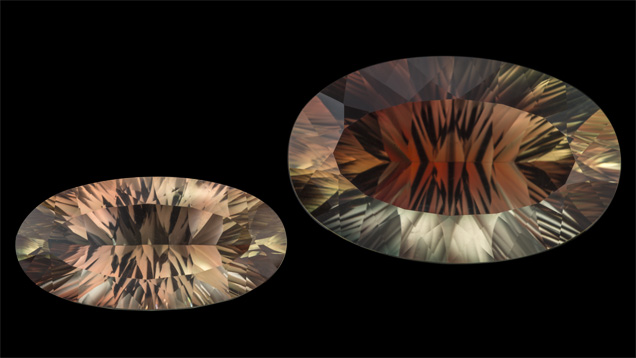

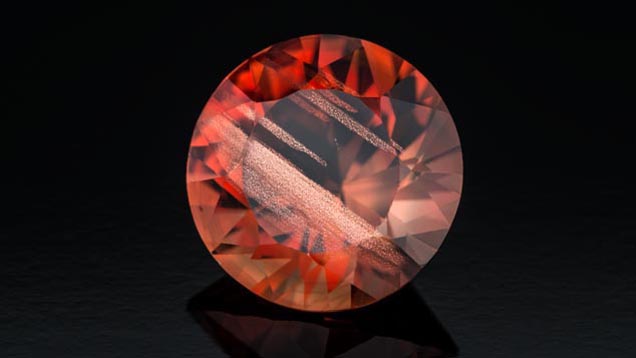

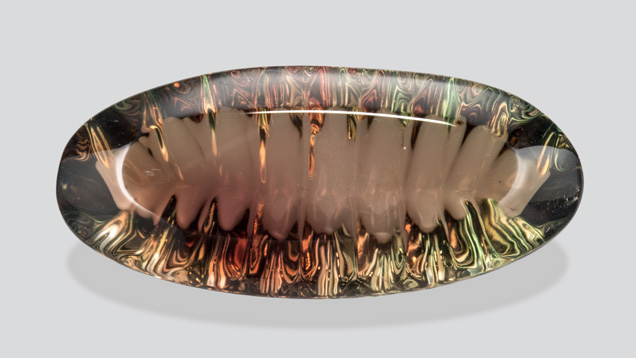

We ask him to tell us what’s so unusual about his mine. “The most unusual thing is the size of our Oregon sunstones,” he responds. “We produce a lot between 100 and 400 to 500 carats.”

It’s not just the size though, he explains, it’s the color too: “About seventy-five percent of our sunstone has green in it, which is one of our rarest colors, and we get a lot of the teal—which is bluish green—very, very rare for sunstone.”

In spite of this mine’s advantages over others in the area, Dave still comes up against the universal character of his profession: “We’ll hit an area, as always with any kind of mining, that’s kind of dead…We don’t get a lot of color, get a lot of clears…But then, just a couple of feet farther, wham! Right back in the color!”

SUNSTONE BUTTE HISTORY

Dave and Tammy aren’t the only miners who have tried their luck on this hill. Others dug, but found mainly large, clear feldspars, and few colors. They gave up, Dave tells us, “…decided it wasn’t worth it and let go.”Dave was walking the desert looking for prospects when he found this place. He saw plenty of stones on the surface and noticed that the anthills were full of feldspar. He staked out nine claims in the area. However, because Sunstone Butte is outside the established mining area, he had to wait for a year and a half while the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) undertook a full environmental impact study.

WHAT DRIVES YOU TO MINE SUNSTONE?

We eventually get to the questions of why mine here, and why this particular gem? “A friend of mine,” Dave answers, “…his dad’s been coming down here for 50 years, and he was coming down to visit him…He was a co-owner in a co-op down in the sunstone valley and I came down with him on a weekend.” Dave was lucky and found a nice red, so his friend’s father faceted it for him.

This experience gave him the intelligence he needed to look for his own claims as well as the confidence to leave his high-paying job at a major corporation and stake it all on sunstone.

PRESENT AND FUTURE SUCCESS

What’s the secret of the operation’s success, we ask? Dave pauses for a moment: “When I was doing fee digging, I analyzed the other miners.” He explains that, while he agrees the mine’s high-quality output is one factor, he wanted to differentiate his gems from everyone else’s: “Most of the miners were doing more basic cutting…As we started getting our volume out here, I decided I wanted to go more high end…We do a lot of concave…linear cuts…we have a designer that’s making new cuts for us…it’s really taken very well out in the marketplace.”

Dave sums up the couple’s current approach: “Once you get into jewelry, it takes so much of your time, and we love mining…We’d rather just mine, come out in this beautiful desert and enjoy ourselves mining and take three or four months off!”

And the couple’s focus on contemporary cutting and carving? “When somebody sees an absolutely breathtaking piece of jewelry, or a carving, it’s a buzz again…word gets out there,” Dave explains. “We’re pretty proud of how we’ve impacted the sunstone industry in the last three years,” he finishes with a smile.

Duncan Pay is editor-in-chief of Gems & Gemology, Robert Weldon is manager of photography and visual communications at GIA in Carlsbad, and Kevin Schumacher is digital resources specialist at GIA in Carlsbad.

The authors would like to thank all the sunstone miners for their generosity of spirit and the time they committed to showing us every detail of their mining operations; nothing was too much trouble, and we were made to feel at home everywhere we visited. We thank John Woodmark and his crew at the Ponderosa mine; Don Buford, Terry Clarke, and Mark Shore at the Dust Devil mine; Dave Wheatley, Tammy Moreau, and David Grey at the Sunstone Butte mine; along with Nirinjan Khalsa and especially Mariana Photiou for their help liaising with the miners.