A Sunstone Odyssey,

Part 1: The Ponderosa

October 23, 2013

THE MINE'S LOCATION

This connection to the native people extends to the present day. Woodmark partners with the local tribal outreach program to offer seasonal employment to Native American teens at the Ponderosa mine. This is something Woodmark is very proud of, and we’ll return to it a little later.

Right now, we’re standing on the steep slopes of Donnelly Butte, just above the Ponderosa mine’s pit. At our backs, magnificent stands of lofty ponderosa pines extend uphill. We are about a five-hour drive from Portland, Oregon, and the transition from that busy city to the silence and serenity of the Ponderosa is jarring.

Beneath us, entombed in an ancient lava flow, millions of carats of rough sunstone—Oregon’s state gemstone—await discovery. The Ponderosa mine is possibly the state’s most important source of the repeatable commercial sizes required by jewelry manufacturers.

Beyond the direct environmental impact, Woodmark and his crew also have to synchronize their mining to the regional climate. These are Oregon’s High Lava Plains, after all, and the winters can be brutal: “The mine is located at 5900 ft., so from October to June we’re covered with as much as ten feet of snow up here, so there’s absolutely no mining during those months.”

Despite these constraints, he knows the Ponderosa’s weathered reddish basalts are blessed with high concentrations of sunstone: “This mine is tremendously rich—the whole mine is 60 acres—and we get a kilo and a half of sunstone out of every cubic yard of dirt moved…so it’s arguably one of the richest gemstone mines in the world.”

Because of the richness of this deposit and the weathered nature of the basalt around the gems, they’re easier to recover than at some of Oregon’s other sunstone locations. Woodmark explains: “We do ten-day mining stints…sometimes four to five times throughout that four month period…It all depends on the demand for Oregon sunstones…the more demand, the more often we mine.”

BEAUTIFUL SUNSTONE

Woodmark is passionate about sunstone: “You never get tired of it…it isn’t like you’re mining amethyst, which is all purple. Ours is so many different colors, every stone is unique.” As he talks on, his enthusiasm and love of this unique gem is infectious: “You can get reds, with just a sprinkling of the copper platelets, which makes it look like you’re looking into a red sky with gold stars…It’s just gorgeous.”

THE PONDEROSA MINING PROCESS

Woodmark is determined that we see all of the mine’s operations and witness the recovery of gem sunstone directly from the pit wall. We start right at the wall, which bears sets of deep, parallel gouges. He mentions this is the work of the “magic finger,” developed by a member of his crew as an attachment for their backhoe, and which makes mining much easier.

Woodmark adds that the backhoe’s special attachment—basically a flattened metal spike—was the missing ingredient: “We haven’t monkeyed around with anything else since we got our ‘magic finger’ to break this stuff down. Before, it was too hard for our machines to work.”

Once enough of the pit wall is torn down by the backhoe, a small loader moves the ore onto an area of the pit floor. Next, the Ponderosa crew runs their massive forty-thousand pound loader over the material to crush it and loosen the stones.

The loader feeds the crushed rock through a dry trommel—a rotating screen that, with the harsh clatter of stone on metal, separates the dirt from the ore-bearing material. The next stage is a second trommel, this time using water. John tells us this piece of equipment takes the concentrate and “washes it, scrubs it, and knocks off a little bit of the volcanic crust that’s on the crystals.”

One load fills about twenty five-gallon buckets. The buckets quickly stack up behind each of the three screening stations set up at the time of our visit.

A picker stands behind each screen. Woodmark picks up a bucket of concentrate and pours the contents onto a screen to demonstrate for us: “We…throw all the big rocks off…spread it out fairly evenly…” He picks up a hose and directs a jet of water over the concentrate. “…then come back and spray it down.”

He pauses to pick up a choice piece of sunstone. “Nice red,” he observes. “And then we start…systematically going through the whole screen.” With a small trowel, he works methodically from one end of the screen to the other, telling us, “What we try and do is turn every stone…leave no stone unturned we tell the kids…so you start at one end and you just systematically turn every stone.”

John emphasizes that speed is of the essence: It’s important to go through the screens quickly but accurately. “Don’t miss a thing, and get on to the next screen.” His rule of thumb is that the more screens you go through, the more you’re going to make: “I’ll do a screen every five-to-six minutes…it’s important not to jump around…because you’ll start to miss them.”

John’s eyes scan methodically from one end of the screen to the other, his trowel making quick movements to flip over the larger pieces: “A lot of our stones have a volcanic crust on them and even though they’ve gone through all the processes to get here, they’re very hard to find, so we go through it very methodically.”

“Don’t leave a stone unturned…” he admonishes us, “…because sure enough, there will be a red one hiding underneath there…and we don’t want to miss a red one.”

Once all the concentrate from a load is recovered, it’s washed for about an hour in a small cement mixer, which takes about 35 kilos at a time (60-70 pounds). “It’s almost like a rock tumbler…a giant rock tumbler,” Woodmark jokes.

When John tips out the mixer, there’s a crystalline glitter and tinkle as freshly washed rough cascades onto a small screen. “I’m looking for how many reds and how much schiller is in there…I’m looking for good stones that will bring money.”

He plucks out a limpid chunk of feldspar. “There’s a beautiful yellow…it’s a nice big size…see how clear and nice that stone is…that’ll make a terrific stone.” And then, a better prize: “Here’s a beautiful red…that’s going to make a tremendous faceted stone!”

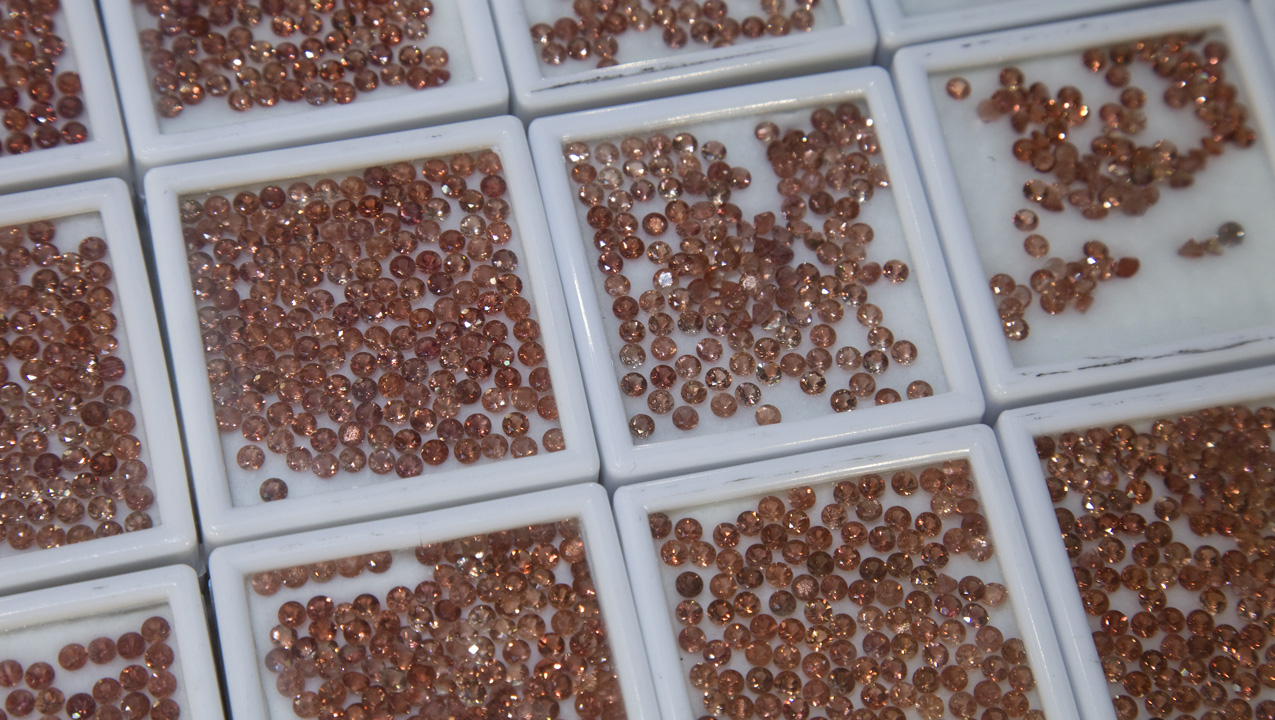

The final step at the mine is to grade all this freshly cleaned concentrate. John leads us to a small table in front of the mine’s bunkhouse, where trays of sorted rough—reds, bicolors, schiller stones, yellows, and clears—rest in water-filled metal trays. The water cuts down reflections and helps with grading, he explains. There, in the shadow of tall ponderosa pines, John outlines the qualities a really fine gem might have: “The pinnacle is if it would be good enough to make a carving. A carving has to be something over 25 carats finished.”

He continues, “It has to have all the attributes…color…schiller…so it really is the pinnacle of an Oregon sunstone…We sell them for a lot of money…That’s just one in thousands of stones that we find.”

NATIVE AMERICAN PICKERS

John is proud of his partnership with the local tribal outreach program, which started with five kids in 2006 and continues to the present. “We’ll pick for ten days at a stint,” John tells us. “After ten days, they’re burnt out picking stones and standing down there in the hot sun.”

Photo by Robert Weldon

PROFIT

Woodmark is a savvy businessman, successful in many ventures before he acquired the Ponderosa mine. He applies the same financial acumen to sunstone as he would to any other commodity; “A kilo of red is worth twenty thousand dollars…we’ve got 25 of them in five days.”

THE GREAT ANDESINE CONTROVERSY

When we ask John about the andesine issue, there’s a hint of resignation in his answer. “Around 2004 or so, we started running into resistance because of a product out of China called andesine.” He explains that the jewelry channels jumped on it because every stone looked exactly alike, and as he puts it, “They could get them for nothing and sell them for a lot.”Then for four years, while gemologists and geologists the world over tried to prove the authenticity or treated nature of this new gem, sales of Oregon sunstone were flat because people were afraid to invest. John is pragmatic on this topic: “We got hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of gemologists’ time and effort to prove that the andesine was a treated stone, but it also verified that Oregon sunstone was all natural.”

John contends that all the publicity over andesine was, in reality, a public relations blessing. “Nobody ever heard about Oregon sunstone before this andesine mess. Now everybody knows andesine was trying to be like an Oregon sunstone.”

In the three years since andesine’s treated nature was confirmed, John asserts his sales have increased year on year.

SELLING SUNSTONE

Most consumers know about diamond, ruby, sapphire, and emerald, and might well favor those Big 4 gems. John understands it takes time and effort to open peoples’ eyes to sunstone’s unique attributes. “You have to sell an Oregon sunstone,” he says. “Most customers don’t know what it is.”“The whole process of educating people and telling them about it,” he explains, “makes the stone personal.”

One of the qualities that make handling sunstone a challenge for commercial jewelry manufacturers—the uniqueness of individual gems might make them hard to match in jewelry—can play well with enlightened consumers looking for something different.

“We tell them about the uniqueness of having the copper particles in the stone, which makes their stone as unique as a snowflake,” John continues. Finally, he adds another set of strengths: “This is an American gemstone, picked by Native Americans…It’s only found in America, and it’s rare and exotic…so you know, it’s a terrific stone.”

Duncan Pay is editor-in-chief of Gems & Gemology, Robert Weldon is manager of photography and visual communications at GIA in Carlsbad, and Kevin Schumacher is digital resources specialist at GIA in Carlsbad.

The authors would like to thank all the sunstone miners for their generosity of spirit and the time they committed to showing us every detail of their mining operations; nothing was too much trouble, and we were made to feel at home everywhere we visited. We thank John Woodmark and his crew at the Ponderosa mine; Don Buford, Terry Clarke, and Mark Shore at the Dust Devil mine; Dave Wheatley, Tammy Moreau, and David Grey at the Sunstone Butte mine; along with Nirinjan Khalsa and especially Mariana Photiou for their help liaising with the miners.

.jpg)