Characterization of Emeralds from Zhen’an County in Shaanxi, China

ABSTRACT

In 2017, the first emerald deposit in the Qinling Orogenic Belt was found in Zhen’an County, Shaanxi Province, China. This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the gemological, spectroscopic, and trace element characteristics of a select set of Zhen’an emerald samples based on standard and advanced gemological methods, including gem microscopy, ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry. Microscopic studies revealed that Zhen’an emerald exhibits longitudinal striations and inclined growth steps on its hexagonal prism faces and contains an abundance of two-phase (gas/liquid) fluid inclusions. A variety of mineral inclusions were identified, including phlogopite, plagioclase, scheelite, calcite, talc, and hematite. Some crystals display color zoning, with a deeper green rim containing elevated vanadium and iron. Zhen’an emerald’s dominant chromophore is vanadium, and the material is characterized by a high vanadium concentration, notably low chromium, a moderate iron concentration, and an elevated ratio of gallium to cesium. These unique geochemical signatures of Zhen’an emerald, along with their internal features, could be a robust tool for discerning emerald from this deposit.

Prominent emerald-producing regions in Asia encompass Panjshir in Afghanistan; Swat in Pakistan; Rajasthan in India; Malipo in Yunnan, China; and Davdar in Xinjiang, China, which are within or adjacent to the Himalayan Orogenic Belt (Marshall et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Cui et al., 2023). In 2017, emerald was also discovered within the Qinling Orogenic Belt in central China, in Zhen’an County of the Shaanxi Province (Dai et al., 2017, 2018).

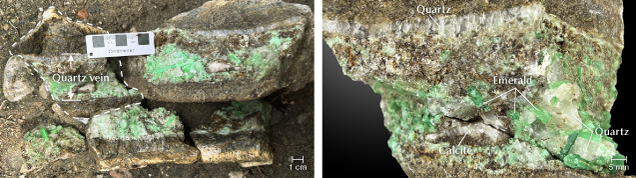

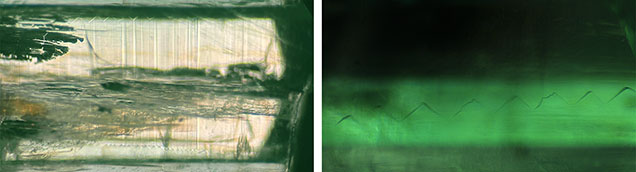

Sporadic reports of emerald occurrences in Zhen’an County first emerged in 2017. The emeralds in those reports were primarily found in deep drilling samples. Recent discoveries of emerald outcrops in the area, including those found in 2025, have established Zhen’an as the third emerald deposit in China. The emeralds extracted from local tungsten-beryllium mines in Zhen’an County are sourced from quartz or quartz-calcite veins and are often associated with minerals such as mica, scheelite, and wolframite (Dai et al., 2017, 2018, 2019). The emerald crystals range in color from light bluish green to vivid bluish green, displaying a slight deepening of hue from core to rim, and are characterized by abundant fluid inclusions—particularly two-phase (gas/liquid) fluid inclusions (Dai et al., 2018, 2019; Dong et al., 2023a). Most emeralds are translucent and have many cracks, but a few are transparent and of gem quality (figure 1). The gem-quality crystals typically measure approximately 5 mm. Recently, emeralds of roughly 20 × 20 mm and 10 × 60 mm have been sporadically discovered.

Emerald is defined as a green variety of beryl colored by chromium and/or vanadium. Vanadium dominates as the primary chromophore in emerald from only a few deposits; notable examples are emeralds from Malipo in Yunnan, China (Hu and Lu, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019); Byrud in Eidsvoll, Norway (Loughrey et al., 2013); and Lened, Canada (Lake et al., 2017). The chromophore composition of Zhen’an emerald is comparable to that of Malipo emerald; in both cases, the vanadium content is significantly higher than the chromium content (Dai et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2023b). The aluminum within the emerald is octahedral in coordination and is substituted by elements including magnesium, iron, manganese, chromium, and vanadium (Dai et al., 2018).

For this study, 26 emerald samples were collected from Zhen’an County (southern Shaanxi Province, Central China) by authors X-YY and YG as well as local miners and farmers. Surface micromorphology, inclusion characteristics, spectral features, and chemical composition of the samples were systematically measured and analyzed using standard gemological testing, spectroscopic methods, and quantitative analysis. These results were used to elucidate the gemological properties and color mechanism and, crucially, to aid in the geographic origin determination of emeralds from this new deposit.

HISTORY AND GEOLOGY

Emeralds in China have been found in three deposits: Malipo in Yunnan, Davdar in Xinjiang, and Zhen’an in Shaanxi (Marshall et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2017, 2018, 2019; Hu and Lu, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2023). Zhen’an in Shaanxi represents the most recent discovery among the three and is the sole emerald deposit within the central Qinling Orogenic Belt in China.

Following the discovery in Zhen’an of a beryl and wolframite syngenetic mineral association, Dai (2017, 2018, and 2019) discovered another mineral association of emerald and scheelite in the Hetaoping tungsten-beryllium mine in Zhen’an. Over the past few decades, local villagers have reported the occasional unearthing of green stones resembling beryl, although the true nature of these stones was unknown. In recent years, some villagers and/or miners have kept specimens of beryl mined from nearby tungsten deposits (figure 2).

The Hetaoping tungsten-beryllium deposit, which hosts emeralds, is situated in western Zhen’an County. Currently, all the known emerald deposits in Zhen’an County are found within the tungsten mining districts, located tectonically in the South Qinling Belt between the Shangdan and Mianlue suture zones (figure 3). The South Qinling Belt is a significant component of the Qinling Orogenic Belt in central China and belongs to the passive continental margins (Zhang et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2018, 2019; He et al., 2024; Dai et al., 2024). The outcropping strata in this area predominantly consist of Paleozoic carbonate rocks and Mesozoic magmatic rocks, mainly intermediate to felsic igneous rocks such as Dongjiangkou and Yanzhiba granites (Zhang et al., 1996; Xu et al., 2012). The development of tectonic structures including fold, thrust-nappe, and strike-slip faults provided channels for the migration of mineralizing hydrothermal fluids, and also resulted in a large number of tensile and torsional secondary fault structures that became the main ore-bearing spaces (Zhang et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2012). The Yuehe fault is the most important tungsten-beryllium ore-controlling fault (Dai et al., 2018; He et al., 2024).

The emerald deposits are situated on different slopes of the Qinling Mountains, from Hetaoping to Dongyang (figure 4A). Emeralds from Zhen’an are mainly hosted within quartz veins (figures 2, 4B, and 4C) and quartz-calcite veins (figure 5). Most of the emerald crystals range from 0.5 to 2.0 cm in length, with a few longer than 5 cm, including the largest crystal found to date at 6.3 cm long (figure 6). The associated minerals primarily include quartz, scheelite, wolframite, and chromium mica (Dai et al., 2017, 2018, 2019). The argon-argon dating method has yielded plateau ages of 201.4 ± 2.10 Ma for fuchsite and 196.6 ± 2.38 Ma for phlogopite (Dai et al., 2019). The elevated vanadium content in these emeralds may have originated from vanadium-bearing carbonaceous slate and phlogopite schist within the region, and the source of beryllium is believed to be derived from hidden felsic magmatic intrusions (Dai et al., 2018).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

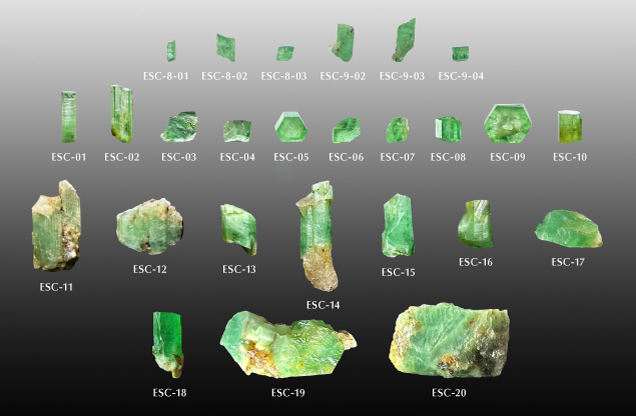

Samples. A total of 26 emerald samples from Zhen’an County, Shaanxi Province, China (figure 7) were examined. Six emerald samples (ESC-8-01, ESC-8-02, ESC-8-03, ESC-9-02, ESC-9-03, and ESC-9-04 were collected in the field from a variety of mines by authors X-YY and YG. The remainder (ESC-01 through ESC-20) were selected from more than 200 emerald crystals collected by an enthusiast who obtained them from local miners and farmers over the past several years. These samples include both partially fractured and well-formed euhedral columnar single crystals exhibiting a typical beryl crystal morphology.

Standard Gemological Testing. Conventional gemological analyses of the samples were performed at the Gemological Research Laboratory of China University of Geosciences, Beijing. Each sample was examined using a refractometer, Chelsea filter, long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (254 nm) ultraviolet (UV) lamps, and an apparatus for determining specific gravity using the hydrostatic method. Internal and external features were observed with a GI-MP22 gemological microscope utilizing darkfield, brightfield, and oblique illumination techniques. To best capture the inclusion scenes, some photomicrographs were enhanced by focus stacking techniques.

Spectroscopic Methods. Ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer in diffuse reflection mode. The results were expressed in terms of absorbance, which was accomplished by converting the directly obtained reflectance using the Kubelka-Munk transformation. The instrument was equipped with an ISR-3100 60 mm diameter integrating sphere. Measurements were taken at a sampling interval of 1 nm, using a slit width of 20 nm, and covering a wavelength range from 300 to 900 nm.

Raman spectra were acquired using a Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution Raman spectrometer at the Gemological Research Laboratory of China University of Geosciences, Beijing, employing an argon-ion laser with 532 nm excitation. The spectral range covered was 4000 to 100 cm–1, with an integration time of 5 s and accumulation of up to 3 scans. The Raman shifts were calibrated using monocrystalline silicon prior to testing, with a tolerance of ±0.5 cm–1.

For minerals that could not be identified solely by Raman analysis, particularly those with low hardness, the destructive KBr pellet transmission method of infrared spectroscopy was employed. Infrared spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, with the resolution set at 4 cm–1 and a scanning range of 4000 to 400 cm–1.

Trace Element Chemistry. In situ trace element measurements were conducted using a Thermo-Finnigan Element II sector field inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometer paired with an NWR193UC laser ablation system at the National Research Center for Geoanalysis, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (CAGS), Beijing. The ablation spots on the emerald samples measured 40 μm and were performed using a repetition rate of 20 Hz and a laser energy density of approximately 5 J/cm2. Helium was used as the carrier gas for the aerosol generated by laser ablation. The instrument was optimized by ablating NIST SRM 612 to achieve maximum signal intensity for lanthanum and thorium (4 × 105 cps), while maintaining oxide production (ThO+/Th+) well below 0.2%. Each analysis lasted for 80 s: 20 s for background acquisition, 40 s for data acquisition during ablation, and 20 s for post-ablation washout. Trace element concentrations were calculated offline using Iolite software for internal standardization, with NIST 610 and KL-2G serving as external calibration standards (GeoReM preferred values) (Woodhead et al., 2007; Paton et al., 2011).

RESULTS

Gemological Properties. The Zhen’an emerald samples used in this study displayed a light to medium saturation of green, with a yellow or blue tone.

The refractive index of the samples ranged from 1.568 to 1.578 for the extraordinary direction (ne) and from 1.576 to 1.587 for the ordinary direction (no), yielding a birefringence of 0.008 to 0.009, consistent with emerald’s uniaxial negative character. The specific gravity of the samples varied between 2.64 and 2.72, while the specific gravity of emerald crystals devoid of other associated minerals falls predominantly within the range of 2.68 to 2.70. All samples were unresponsive under the Chelsea color filter and inert under both long- and short-wave UV radiation. A summary of the gemological properties is provided in table 1.

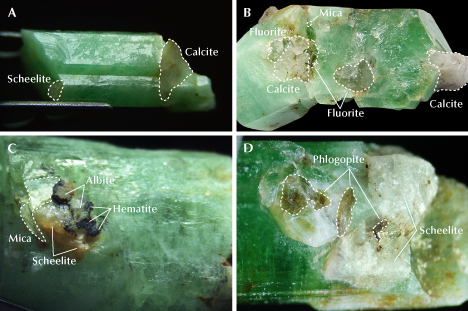

Microscopic Characteristics. Emerald crystals from Zhen’an are generally associated with quartz, muscovite, phlogopite, calcite, albite, scheelite, fluorite, and hematite. In this assemblage, mica is green or brown, and calcite and albite are white or yellow (figure 8).

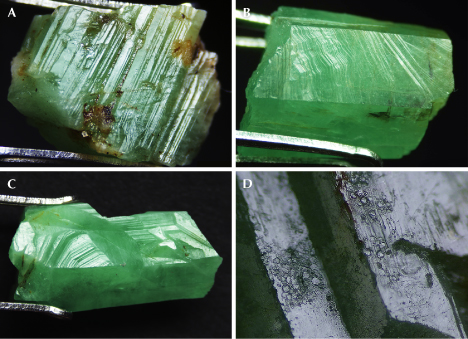

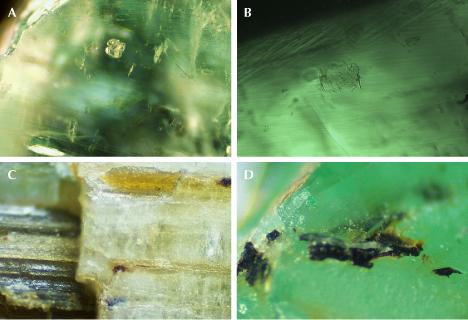

Some of the emeralds studied had distinct hexagonal color zoning around the c-axis, ranging from a green rim to a near-colorless core (again, see figure 7), or flat color bands visible on the prismatic plane. A series of rectilinear stripes (combination striations) parallel to the c-axis were visible on the hexagonal column faces (figure 9A). Additionally, oblique striations were observed on the prismatic faces of certain samples (figure 9B), interpreted as growth steps rather than combination striations (Schmetzer and Martayan, 2023). Notably, these growth steps exhibited angular characteristics sometimes approaching an angle of 120° (figure 9C). A variety of etch features were seen on the surface of one of the hexagonal basal pinacoidal faces: irregular etch pits and hexagonal etch pits (figure 9D). Growth steps were observed at the edge of the prismatic face. Incomplete cleavage parallel to the bottom c face was seen on the surface.

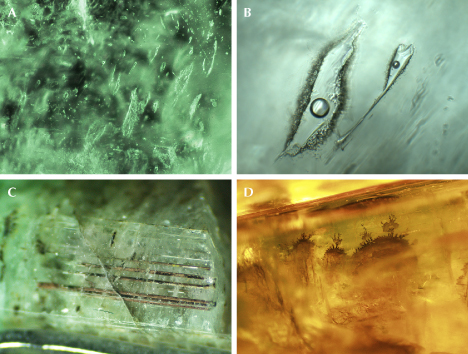

Distinct linear zigzag inclusions, oriented parallel to the c-axis, were identified first within sample ESC-02 (figure 10). Found in four emerald samples, the linear zigzag inclusions appeared in pairs.

The most common inclusion type in the Zhen’an emeralds studied was a two-phase inclusion with a gas bubble suspended in fluid (figure 11). These two-phase inclusions were several to hundreds of micrometers in length and a few to tens of micrometers in width. The inclusions exhibited a variety of forms, including elongated, tubular, needle-like, long-tailed, eye-like, and various irregular shapes. Some were clustered in groups within the confines of a healed fissure surface (figure 11A), while others were found in isolation (figure 11B). The tubular inclusions were parallel to the c-axis, which measured approximately 4 mm in length, and some subsequently had been filled with black hematite and magnetite adhered to the inner walls of the voids (figure 11C). Secondary inclusions also occur in other morphologies (figure 11D).

The components of isolated primary two- or three-phase fluid inclusions in Zhen’an emeralds were identified by Raman spectroscopy. An eye-like two-phase fluid inclusion, measuring approximately 0.10 mm in length, was subjected to Raman analysis (figure 12). The results suggested water (H2O) as the liquid phase (identified by a wide absorption band near 3400 cm–1) and carbon dioxide (CO2) as the gas phase (identified by peaks at 1289 and 1393 cm–1). The Raman spectra of other two- or three-phase fluid inclusions revealed only the identity of the gas phase (figures 13 and 14), which indicated that the components could be CO2 (1287 and 1389 cm–1) plus nitrogen (2330 cm–1), or CO2 (1280 and 1385 cm–1) plus methane (2911 cm–1).

Mineral inclusions in the Zhen’an emeralds studied were abundant, with plagioclase and phlogopite particularly prevalent (figure 15). Plagioclase inclusions occurred in clusters, while phlogopite inclusions were observed in the form of lamellar rectangles and hexagons. Euhedral scheelite and rounded calcite inclusions were also encountered within the emerald crystals. Among the aforementioned mineral inclusions, calcite, plagioclase, and scheelite were all colorless, while phlogopite was nearly colorless with a slight brownish tint. In addition, at one end of sample ESC-05, brown-yellow, greasy, lustrous talc columns (indicated by FTIR) filled the emerald crystals; some of these were exposed and fractured. Brown and brown-black hematite inclusions were also found, usually in the form of irregularly shaped flakes.

Trace Element Chemistry. The emerald samples were classified into two groups based on color: bluish green (22 samples) and yellowish green (ESC-07, ESC-10, ESC-16, and ESC-19). From each category, two samples were randomly selected for trace element analysis. For each sample, three to four spots were randomly chosen for laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) testing, and the results are shown in table 2.

Concentrations of alkali metals in the emerald samples from Zhen’an, from highest to lowest, were sodium (5802–7948 ppm, with an average of 6636 ppm), cesium (715–1585 ppm, average 1188 ppm), lithium (279–627 ppm, average 400 ppm), potassium (90–716 ppm, average 193 ppm), and rubidium (17–42 ppm, average 26 ppm). The combined content of these alkali metal elements varied between 7650 and 9583 ppm, with an average of 7897 ppm.

Beryl that is colored green by chromium and/or vanadium is considered emerald. In these emeralds, vanadium ranged from 1047 to 3031 ppm (average 2252 ppm); chromium did not exceed 178 ppm (average 42 ppm); and iron varied between 951 and 1968 ppm (average 1210 ppm). The chromium content of ESC-19 was below the detection limit. It is evident that the total concentration of monovalent cations (Li+ + Na+ + K+ + Rb+ + Cs+) consistently surpasses that of divalent cations (Mg2+ + Mn2+ + Fe2+ + Zn2+), even if all iron, including Fe3+, is regarded as Fe2+. This observation may suggest a substitution of Li+ for Be2+ at the beryllium site within the crystal structure of emeralds from Zhen’an (Groat et al., 2008). However, this explanation alone is insufficient to account for all observed chemical characteristics. Additionally, it may imply the presence of Al3+ substituting for Si4+ at the silicon site.

Some samples showed obvious color zoning, which was explored by looking at the trace element concentrations across these zones for two different samples. The trace element concentrations of samples ESC-09 and ESC-10 with obvious color zones are given in table 3. Figure 16 illustrates the seven analytical spots on ESC-09, the five analytical spots on ESC-10, and the associated elemental variations. Overall, the chromium concentration exhibited considerable fluctuation. Within the near-colorless core of the emerald, the concentrations of manganese and chromium displayed notable variability, whereas the levels of magnesium, vanadium, cesium, iron, zinc, rubidium, and scandium remained relatively stable. Progressing from the core to the periphery of the emerald crystal, where the green hue intensified, a pronounced increase in the concentrations of vanadium, cesium, iron, manganese, gallium, and scandium was detected, along with a significant decline in zinc levels.

The content of most elements (except for chromium) showed no significant fluctuations in the core, indicating a relatively stable growth environment during the emeralds’ initial crystallization stage (Yu et al., 2020). The variations in trace elements from the core to the rim suggested fluid evolution during the crystallization process or multistage mineralization of the emeralds (Yu et al., 2020; Cui et al., 2023). Additionally, the changes in chromophore elements confirmed vanadium as the primary chromophore in Zhen’an emeralds.

UV-Vis-NIR Absorption Spectroscopy. The spectra of 11 oriented emerald samples (ESC-8-03, ESC-9-04, ESC-01, ESC-02, and ESC-04 through ESC-10) were collected both parallel to the c-axis and perpendicular to the c-axis in diffuse reflection mode. They each exhibited distinctive vanadium-absorption spectra. The representative UV-Vis-NIR spectra of Zhen’an emerald sample ESC-09 are shown in figure 17.

Four characteristic absorption bands were detected: a weak band around 373 nm, a sharp band around 429 nm, and two broad bands around 600–680 and 750–900 nm. The absorption around 373 nm was assigned to Fe3+ (Saeseaw et al., 2019). The two absorption maxima around 429 and 617 nm were assigned to V3+, according to the absorption of vanadium-doped synthetic emerald and emerald from Malipo, Yunnan (Schmetzer et al., 2006; Hu and Lu, 2019, respectively). These absorption features of V3+ ions were prominent in all the emerald samples tested. The absorption maximum around 830 nm was caused by Fe2+ (Wood and Nassau, 1968).

The differences in the UV-Vis-NIR spectra obtained from the two orientations were primarily reflected in the V3+ absorption broad band near 615 nm and the Fe2+ absorption broad band around 830 nm. Additionally, a noticeable difference in the Fe3+ absorption at 373 nm and V3+ absorption at 429 nm was observed: when the measurement was taken parallel to the c-axis, the absorption intensity of Fe3+ was closer to that of V3+ at 429 nm, whereas when the measurement was taken perpendicular to the c-axis, the Fe3+ absorption appeared more like a shoulder peak adjacent to the sharp V3+ absorption peak at 429 nm.

Raman Spectroscopy. The Raman spectra of Zhen’an emeralds were measured perpendicular to the c-axis. The Raman spectra of the carefully polished regions on m faces from all 23 emerald samples were acquired. All of the spectra were nearly identical, and a representative spectrum is shown in figure 18. The characteristic absorption bands of emerald around 526, 685, and 1068 cm–1 were caused by Al-O, Be-O, and Si-O stretching vibrations, respectively (Łodzinski et al., 2005). The Raman spectra indicated that both types of water exist in Zhen’an emeralds—type I and type II—and the Raman features of type I (3606 cm–1) were generally more intense than those of type II (3597 cm–1). A lattice vibration related to the beryl structure, specifically the silica tetrahedra in six-membered rings, shows characteristic bands at 322, 395, and 445 cm–1.

DISCUSSION

Microscopic Characteristics. In addition to the longitudinal striations on the prismatic faces, inclined stripes are generally seen on some long, parallel hexagonal prism faces parallel to the c-axis of the emeralds from Zhen’an. These inclined stripes exhibit an overall stepped pattern rather than complete parallelism, with some individual stripes also displaying a stepped morphology (again, see figure 9B). Hence, they are interpreted as growth steps preserved on crystal planes during crystal development via a layer-by-layer growth mechanism. The hexagonal prism faces parallel to the c-axis of an emerald crystal are often visible with longitudinal striations and sometimes growth steps (Hu and Lu, 2019; Schmetzer and Martayan, 2023). The presence of longitudinal striations and the prevalence of growth steps on the hexagonal cylinder may be indicative of a distinctive characteristic exhibited by Zhen’an emerald.

The morphology of linear inclusions with a zigzag shape, which extend parallel to the c-axis, resemble the helical inclusions observed in Colombian emerald (Okada and Siritheerakul, 2019) and the zigzag growth line inclusions in aquamarine (Gao et al., 2023). However, no fluid inclusions were found surrounding the linear zigzag inclusions within Zhen’an emeralds (again, see figure 10), suggesting that they are more likely attributed to crystal structure and growth than to fluid inclusions. Therefore, such inclusions can also be referred to as zigzag growth lines.

The emeralds from Zhen’an are rich in fluid inclusions, especially gas-liquid two-phase fluid inclusions with less than 50% of the fluid-filled cavity volume occupied by bubbles. The compositions of the gas phases identified include carbon dioxide, carbon dioxide plus nitrogen, or carbon dioxide plus methane. Although no fluid inclusions containing daughter crystals have been identified thus far, the presence of abundant mineral inclusions has been observed, including phlogopite, plagioclase, scheelite, calcite, and hematite, which also serve as associated minerals. These inclusions were commonly observed in the Zhen’an emerald samples, whereas Malipo emeralds, which also exhibit high vanadium content, typically display distinctive dravite (Jiang et al., 2019; Long et al., 2021). This characteristic feature aids in distinguishing emeralds originating from these two mining regions with microscopic examination. Furthermore, the presence of distinct mineral inclusions also serves as an indicator of the heterogeneous nature of the surrounding rock and divergent formation environments within the two mining regions (Jiang et al., 2019; Long et al., 2021).

Color Mechanism. The primary chromogenic element responsible for the green color of Zhen’an emerald is vanadium rather than chromium. Despite the overlapping absorption bands of vanadium and chromium around 620 nm, the broad absorption band at 617 nm in Zhen’an emerald (again, see figure 17), which lacks the sharp bands around 640 and 682 nm, is primarily attributed to vanadium (Wood and Nassau, 1968; Hu and Lu, 2019; Saeseaw et al., 2019). This characteristic vanadium spectrum is similar to that of Malipo emeralds from Yunnan Province, which helps distinguish them from emeralds found in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Davdar in China (Wood and Nassau, 1968; Hu and Lu, 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Furthermore, the shift of the Fe3+ absorption band in the UV-Vis-NIR spectra can be used to help distinguish between Zhen’an emerald and Malipo emerald.

The green coloration in the color-zoned emerald samples is directly related to the presence of V3+, with no obvious positive correlation with Cr3+ (again, see figure 16). Consequently, Zhen’an emeralds are classified as vanadium-dominant emerald (Groat et al., 2008).

Geographic Origin Determination. The total alkali metal content (Li + Na + K + Rb + Cs) of the emeralds from Zhen’an ranges from 7650 to 9583 ppm (average 7897 ppm), which fully overlaps with but on average is lower than that of the emeralds from Malipo, whose content ranges from 7164 to 13469 ppm (Bai et al., 2019; Hu and Lu, 2019; Zheng et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2024). Additionally, the absorption strength of type I water is generally higher than that of type II water (again, see figure 18), suggesting a relatively lower alkali metal content in Zhen’an emerald samples (Bersani et al., 2014; Moroz et al., 2000). However, it should be noted that the Raman spectra of water in emeralds from Malipo show three patterns, differing from those of Zhen’an.

In color-zoned Zhen’an emeralds, there is a notable increase in the vanadium, iron, and cesium contents, while the zinc content demonstrates a decrease from core to rim. Additionally, the chromium content, which is always low, fluctuated irregularly from the near-colorless core to the green rim (again, see figure 16). The variation trends of vanadium and iron contents were consistent with those reported by Dai et al. (2018), whereas variations in magnesium content for the samples in this study indicated both increases (ESC-10) and decreases (ESC-09). Therefore, further sample data are required to investigate the variation trend of magnesium content. Moreover, the increasing trends of vanadium, cesium, iron, gallium, and manganese contents from core to rim are consistent with the changes of emeralds with color zoning from Malipo (Yu et al., 2020). Notably, this study also identified a unique downward trend in zinc from core to rim.

Trace element analysis serves as a crucial tool for determining emerald origin (Saeseaw et al., 2019). Zhen’an emerald is characterized by its distinctive trace element signature, which includes high vanadium, relatively low chromium, and moderate iron content, as well as elevated levels of lithium and cesium. Significantly, the chromium content in Zhen’an emerald is substantially lower than its vanadium content, which is a key feature to help differentiate it from emeralds of other origins. The ratio of chromium to vanadium changes with vanadium content, as shown in figure 19, which can distinguish Zhen’an emerald from those from other sources: Poona (Australia), Jos (Nigeria), Panjshir (Afghanistan), Muzo (Colombia), Coscuez (Colombia), La Pita (Colombia), and Lened (Canada). However, there is still some overlap among these mines. Malipo (Yunnan, China) and Eidsvoll (Norway) also exhibit a ratio of chromium to vanadium below 0.2, which is consistent with Zhen’an emeralds.

Figure 20 shows the vanadium-iron-chromium (ppm) ternary diagram of emerald from vanadium-rich mining areas. The very low chromium content causes Zhen’an emerald to fall near the iron-vanadium line, partially overlapping with Malipo emerald. As opposed to Zhen’an emerald, Eidsvoll emerald has high vanadium, low chromium, and low iron.

To further distinguish the provenance of vanadium-dominant emeralds, a lithium versus cesium diagram (figure 21) was plotted. Emeralds from Zhen’an are marked by their higher levels of both lithium and cesium, setting them apart from emeralds from other deposits such as Davdar (Xinjiang, China), Eidsvoll (Norway), Poona (Australia), Jos (Nigeria), Panjshir (Afghanistan), Muzo (Colombia), and Coscuez (Colombia).

The challenge in distinguishing emeralds from Zhen’an and Malipo arises from the significant overlap shown in the above plots. However, a potential solution lies in considering the ratio of gallium to cesium, as illustrated in figure 22. By establishing a threshold of Ga/Cs = 0.013 (with a range of 0.012 to 0.014 also considered acceptable), a clear distinction can be made: Zhen’an emeralds are positioned above this threshold line, while Malipo emeralds fall below it.

Emeralds from Zhen’an can be distinguished from emeralds of other origin using the above series of trace element plots, allowing the separation of vanadium-dominant emeralds.

CONCLUSIONS

Emerald from Zhen’an is mainly found in quartz or quartz-calcite veins and associated with minerals such as muscovite, phlogopite, albitite, scheelite, fluorite, and phenakite. The emerald crystals exhibit an intact hexagonal columnar shape with inclined growth steps on hexagonal prism faces. Abundant internal two-phase fluid inclusions (gas phase of carbon dioxide, carbon dioxide plus nitrogen, or carbon dioxide plus methane; liquid phase of water) and mineral inclusions (phlogopite, plagioclase, scheelite, calcite, talc, and hematite) are present within the crystals. Occasionally distinctive zigzag growth lines appear in pairs within these emeralds.

The vibrant green color of Zhen’an emerald primarily arises from the significant presence of vanadium, which exhibits a distinct absorption spectrum in the visible range. Alkali metal content in Zhen’an samples ranges from 7650 to 9583 ppm (average 7897 ppm). Correspondingly, Raman absorption of type I water (3606 cm–1) is stronger than that of type II water (3597 cm–1).

Emeralds from Zhen’an are characterized by their abundant vanadium (1047–3031 ppm), lithium (279–627 ppm), and cesium (715–1585 ppm) contents; iron concentrations ranging from 951 to 1968 ppm; chromium levels typically below 180 ppm; and a gallium to cesium ratio greater than 0.013. Plots such as the ratio of chromium to vanadium versus vanadium, the vanadium-iron-chromium ternary diagram, and plots of cesium versus lithium and cesium versus gallium are particularly useful for differentiating Zhen’an emerald from vanadium-dominant emerald from other origins.

.jpg)