Structures Behind the Spectacle: A Review of Optical Effects in Phenomenal Gemstones and Their Underlying Nanotextures

ABSTRACT

This article reviews all of the special optical effects of gemstones, including opalescence, chatoyancy, asterism, schiller, and iridescence. The physics of light scattering, reflection, diffraction, and interference is briefly described for qualitative explanations of these optical phenomena. The most up-to-date microscopic investigations of the submicron inclusions and nanotextures in each type of phenomenal stone, along with their mechanistic interpretations, are also summarized. Although the basic principles behind these phenomena are generally understood, quantitative descriptions that directly connect the optical effects and the submicron structures are still lacking for many of these stones. In addition, the formation mechanisms of some of the textures in phenomenal stones are still debated, if not completely elusive.

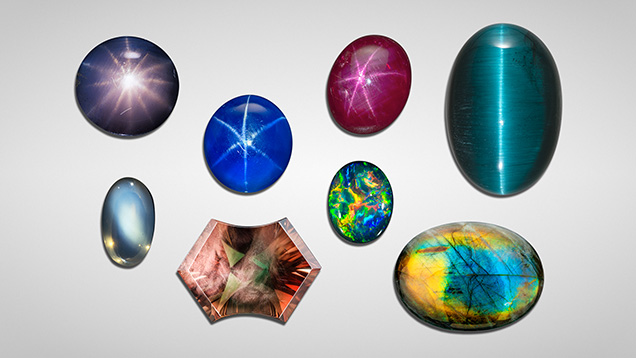

This article roughly sorts the optical effects by the dimensionality and complexity of their underlying submicron structures and textures. Zero-dimensional nanoparticles in diamond and corundum, though typically not considered phenomenal gemstones, produce milky or opalescent appearances by scattering light randomly; one-dimensional oriented needle-like inclusions in chrysoberyl and garnet create cat’s-eye and star effects; two-dimensional platelets and layers in feldspar produce schiller and iridescence by reflection and interference; and three-dimensional photonic crystals in precious opal cause brilliant play-of-color by Laue and Bragg diffraction. The often-confusing past uses of the phenomenal terminology in the literature are also clarified in this article.

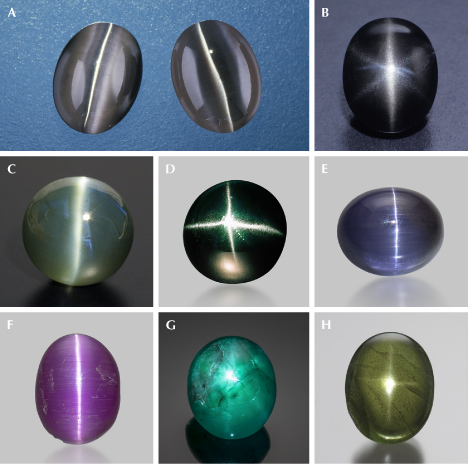

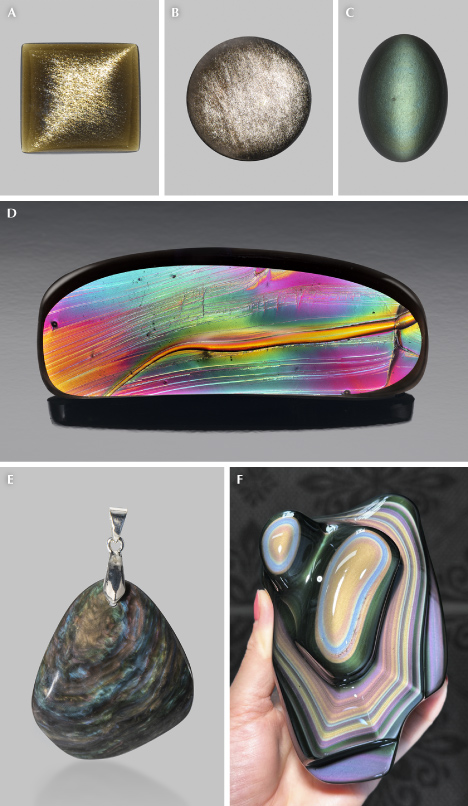

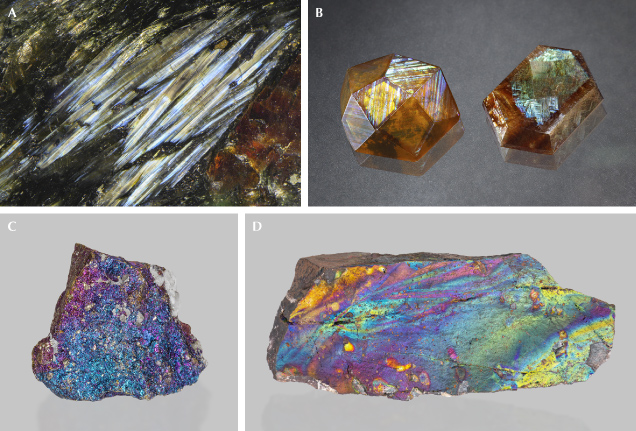

A gem lover might think that all gemstones are phenomenal by definition. However, the term phenomenal gemstones designates a specific group of gem materials that display special optical phenomena under certain lighting or viewing conditions (Shipley, 1945), such as iridescence, schiller, and asterism (figure 1). These gems exhibit a wide range of visual effects created by different internal structures of various sizes and shapes, from diffuse scattering of light by randomly oriented particles to highly directional light reflection or diffraction from aligned or periodic textures. These phenomena can dramatically increase the value of an already valuable stone or even promote an otherwise common mineral into the gemstone category. Phenomenal gemstones substantially diversify the appearances of gemstones beyond the stereotypical sparkling crystals with attractive colors.

The optical effects of phenomenal gemstones reflect fine-scale structures and textures that interact with visible light in intricate ways, and they have drawn the attention of scientists for centuries. However, despite investigations by renowned scientists including David Brewster, C.V. Raman, and Robert Strutt, there is much that we do not understand about phenomenal gemstones, mainly due to the exceptionally small scales of the textures that create the phenomena. Most structures in phenomenal gemstones are internal (unlike the surface coloring structures in the animal kingdom, such as in butterfly wings and bird feathers) and require meticulous sample preparation before they can be studied by advanced imaging techniques such as electron microscopy. In addition, the extremely long geological timescales and complicated crystallization histories that are often required to create these convoluted structures make them challenging, if not impossible, to reproduce through laboratory synthesis.

BOX A: ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES FOR STUDYING PHENOMENAL GEMS |

|

Some analytical techniques commonly used to study the structure of phenomenal stones will be repeatedly mentioned in this article, and it is not possible to fully explain how each one works. For simplicity, the abbreviations used in this article are listed here in order of relevance, along with a brief description of the information each method can provide regarding the analyzed material. XRD: X-ray diffraction. Mainly used to identify crystalline phases by matching the measured diffraction pattern with known structures in a database. Can be used to refine the details of the crystal structure to reveal the atomic ordering state and the chemical composition of the studied mineral. Also can be used to directly determine the crystal structure of an unknown or new material. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy. Can image submicron textures that cannot be resolved by an optical microscope, typically on a polished surface of a material. Image contrast reflects the chemical variations in the material. May also reveal textural contrasts on an etched or freshly broken surface. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy. Can resolve nanoscale textures and even atomic-scale structures. Requires special sample preparation that slices the analyzed material into a very thin foil of less than 100 nm in thickness. Also can create an electron diffraction pattern that can be used to identify the phase and its crystallographic orientation. EDS: Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (sometimes abbreviated as EDX). An instrumental component of SEM or TEM that collects the X-ray spectrum excited by a high-energy electron beam, which can be used to map the chemical composition of the material. Quantitative analysis is possible only using well-characterized reference materials. EPMA: Electron probe microanalysis. Employs the excited X-ray spectrum as in EDS, but with much better precision for quantitative chemical analysis. Well-characterized standard materials are required for quantification. EBSD: Electron backscatter diffraction. An instrumental component of SEM that collects electron diffraction patterns in the backscattered direction, which can be used to identify the crystalline phases and their relative crystallographic orientations. Has much lower resolution compared to the electron diffraction in TEM but can be used to map a much larger area of a sample for statistical analysis. A database of known material structures is required to match the data for phase identification and orientation determination. AFM: Atomic force microscopy. Can resolve the surface texture of a material at the nanoscale by scanning the surface with a tiny mechanical probe. The image may look similar to an SEM image, but it contains quantitative information of the surface height, which cannot be acquired from SEM. APT: Atom probe tomography. A method that can create three-dimensional elemental maps with nanometer resolution, revealing the size, shape, and distribution of tiny clusters, precipitates, or lamellar textures that are smaller than 100 nm. Often used as a complement to TEM. FIB: Focused ion beam. A method that probes the sample using a high-energy beam of atomic ions (most commonly gallium ions). One of the most important applications of FIB is to prepare TEM and APT samples due to its ability to precisely cut the exact region of interest from the analyzed specimen. The secondary electrons created by FIB can also be used for imaging (similar to SEM), while the secondary ions can be analyzed by mass spectrometry. |

Fortunately, studies of phenomenal gemstones have dramatically improved in recent decades, mainly due to the development of more advanced analytical techniques with increasing resolution and accessibility (box A). Professional support for these seemingly inconsequential research projects has historically been limited. However, recent studies have proven that the intricate structures are not only exciting to the curious mind, but they also contain important information regarding the geological processes that created them, which is critical to better understand the history of our planet. Moreover, as a flexible, durable, and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional pigments, colors caused by structural interference have attracted a lot of interest in photonics and material sciences due to their wide range of applications in paints, cosmetics, fabrics, color sensors, wearable electronics, and anti-counterfeiting technologies. A better understanding of the submicron structures of minerals may help push the design and manufacture of these colorful materials beyond biomimicry.

Because of the sophistication of these recent studies, the knowledge gap between the gemology world and mineralogy and physics research is widening faster than ever. It is challenging for gemologists and gem consumers to stay current with the latest updates in the scientific literature, which may be filled with jargon and target only a few experts in their respective fields. Certain inaccurate descriptions and incorrect explanations of phenomenal gemstones from outdated publications are sometimes still cited in recent gemological literature. The new studies cannot be blindly trusted either, as many of them have not yet stood the test of time. Speculation without sufficient supporting evidence is another source of misinformation and confusion, with researchers still struggling to draw solid conclusions. Even experts sometimes fall victim to misinformation, and it is not uncommon to find mislabeled specimens of phenomenal gemstones in famous gem and mineral museums. Misinterpretation of data acquired using advanced techniques is also quite common, as they often exist in abstract and potentially misleading formats that require special expertise for proper processing and interpretation. Finally, the situation is further complicated by often subjective descriptions of the phenomena in gemstones, resulting in poorly defined terminology that is often misused. Different optical effects sometimes look similar, and the same effect may appear dissimilar in different specimens. Multiple phenomena can also occur in the same gemstone, sometimes at different orientations or on different surfaces. A glossary of optical phenomena in gemstones, along with some terms related to crystal intergrowth, is provided in box B in an attempt to clarify the often-confusing terminology.

With this comprehensive review of the status of scientific investigations into optical processes and submicron textures in phenomenal gemstones, the authors hope to clear up some of the confusion and misinformation. This article may also offer guidance for future investigations into optical phenomena in gemstones by providing a summary of what we understand so far and what is still unknown. In this review, the optical processes are only qualitatively explained, with a few necessary mathematical equations, which should be sufficient for a basic understanding. Although some rudimentary knowledge of crystallography and thermodynamics of solid solutions may be required to fully understand every detail, we hope the general concepts are still accessible to anyone who is interested in this subject. This review is also intended as a starting point for those who seek to expand their knowledge of the topic, as most of the relevant literature is referenced in this article.

This article is structured by roughly sorting the different phenomenal gemstones by the increasing dimensionality and complexity of their underlying submicron structures and textures, as outlined by the physical principles explained in boxes C–F. However, we resisted the temptation to firmly separate the phenomenal gemstones into distinct categories because the boundaries between different effects are not as distinct as most would expect (e.g., chatoyancy versus aventurescence). Moreover, many of the descriptions of optical phenomena are qualitative at best, if not outright ambiguous. This article’s order is intended to optimize the logical flow for the reader. For example, the iridescence of pearl and shell is produced primarily by multilayer interference similar to that in labradorite, yet they are discussed last, along with other gemstones that exhibit effects based on diffraction, because the concept of diffraction must be explained first for the reader to appreciate the historical debates regarding the role of diffraction gratings on the surfaces of shells. Also, common opal and precious opal have similar submicron structures but are discussed separately (at the beginning and near the end, respectively) due to their dramatically different visual appearances and optical effects.

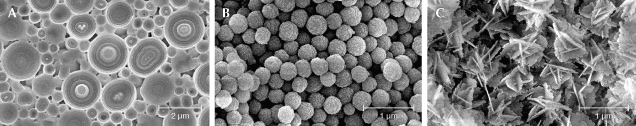

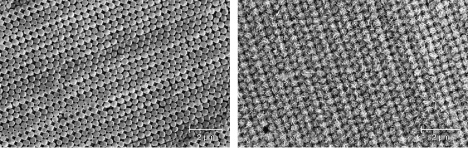

COMMON OPAL

Opal (Opl: SiO2•nH2O) is a silica mineral containing a variable amount of water. Although it is considered a valid mineral name by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) for historical reasons, opal does not fit the technical definition of a mineral and is commonly described as a mineraloid because it is not ordered at the atomic scale. As determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, opals are generally classified into three groups of increasing order: opal-A (amorphous silica), opal-CT (poorly ordered intergrowths of cristobalite and tridymite with amorphous silica), and opal-C (poorly ordered cristobalite with amorphous silica), with many samples showing transitional characteristics between these end members (Curtis et al., 2019). Opal-A can be further divided into opal-AG (amorphous gel, composed of amorphous silica spheres) and opal-AN (amorphous network, also known as hyalite) based on their submicron textures. In general, opals form when meteoric and ground waters dissolve silica from igneous or sedimentary rocks and reprecipitate it within fissures of host rocks (Gaillou et al., 2008). The detailed processes controlling the texture and crystallinity of opal are still not fully understood (Gaillou, 2015), although different models have been proposed and tested (Brown, 2005). A recent study synthesized a material with similar composition and grain sizes to natural opal-AG under geologically relevant conditions (Gouzy et al., 2024). Because opal typically forms at low temperatures, kinetics rather than thermodynamics controls the precipitation process, and opals from different localities can have dramatically variable appearances as a result of diverse chemistries and nanostructures. Opals with no play-of-color are generally called “common opals,” which may also serve as gemstones due to their unique milky appearance (box C) and vibrant colors (figure 2).

Common opals may be considered the paradigm of colloid gemstones, as they consist almost entirely of nano-size silica spheres (figure 3; Gaillou et al., 2008), with the exception of opal-AN. The scattering of light from the randomly arranged nanospheres gives common opal a hazy appearance (figure 2). In fact, the word opalescent is sometimes used to describe the hazy or milky appearance found in other gemstones containing nano-inclusions, such as fancy white diamonds (Eaton-Magaña et al., 2019).

The bodycolor of common opal is mainly controlled by the species of nano-inclusions. For instance, hematite inclusions create yellow, orange, or brown colors; fluorite inclusions can produce purple; and green opals may contain nickel-rich inclusions. The sky-blue color in some opals may be created by scattering, as they appear orange in strong transmitted light (Gaillou, 2015). It is highly debatable, however, whether this is Rayleigh scattering, because most of the nanospheres in opal are too large to scatter visible light (box C). Careful quantitative analysis of the scattered and transmitted spectrum will be necessary to accurately describe the effect (Kinoshita, 2008). Photoluminescence created by uranium (green), unsaturated silica frameworks (blue), or organic compounds (orange) may also affect the apparent color of opal under sunlight, if it is not quenched by high concentrations of iron (Gaillou, 2015).

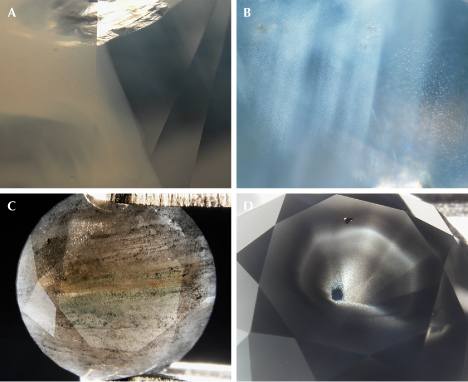

FANCY WHITE AND FANCY BLACK DIAMOND

Among all milky and cloudy gemstones, fancy white and fancy black diamonds are perhaps the most valuable (figure 4). Although it is debated whether white and black are considered colors or not, these special diamonds are graded and reported similarly to other fancy-color diamonds. Therefore, they are generally not considered phenomenal gems even though their “colors” are caused by special optical effects. The gemological properties of both natural fancy white and fancy black diamonds are best summarized by Eaton-Magaña et al. (2019)

Fancy white diamonds owe their hazy or cloudy appearance to dislocation loops and nano-inclusions (Gu and Wang, 2018; Gu et al., 2019). A dislocation is a linear crystallographic defect within the crystal structure where the atomic arrangement changes abruptly. Dislocations in diamond almost always exist as self-enclosed loops due to their localization and lower energy. Experiments at very high temperatures have shown that dislocation loops can form from platelet defects (planar or film defects containing aggregated nitrogen) in type IaB diamonds (Evans et al., 1995; Speich et al., 2017), and a similar process is believed to be responsible for dislocation loops in untreated natural diamonds. Because dislocations are one-dimensional misalignments of atoms in the crystal structure, they fall well below the imaging resolution of an optical microscope (figure 5A). However, they can still scatter light to create the hazy appearance due to the disrupted crystal lattice as well as the strain field around it.

The nano-inclusions found in fancy white diamonds are octahedral-shaped negative crystals, known as voidites, which are approximately 30 to 200 nm in size and contain nitrogen (Barry et al., 1987). These voidites are believed to have formed by the exsolution of excess nitrogen from the diamond lattice (Kiflawi and Bruley, 2000), and they contain mostly solid molecular nitrogen (cubic δ-N2) (Navon et al., 2017; Sobolev et al., 2019; Tschauner et al., 2022). A recent study also showed that oxygen atoms dissolved within the diamond lattice can also exsolve to form voidites filled with CO2 (Shiryaev et al., 2023). Unlike dislocation loops, voidite inclusions are three-dimensional particles, which can be seen as “pinpoints” under high magnification using an optical microscope (the size falls below the resolution of the optical microscope, so they appear as dots) (figure 5B).

Nitrogen defects in diamond crystals start as isolated single nitrogen atoms substituting for carbon atoms (C centers), which can coalesce into pairs (A centers) and eventually four-nitrogen clusters (B centers) over geological time (Boyd et al., 1995). Both dislocation loops and voidites in fancy white diamonds are strongly related to the aggregated nitrogen defects, which are produced by high concentrations of nitrogen impurities and prolonged annealing at high temperature. Therefore, fancy white diamonds are predominantly type IaB (diamonds old enough to contain only B centers), and they originate from Earth’s transition zone or the lower mantle. Because these aggregates form by annealing, no thermal treatment to mimic or enhance the cloudy or hazy appearance of fancy white diamonds has been reported.

The cause of color in natural fancy black diamonds is more complicated, involving dark-colored inclusions such as graphite or iron oxide (hematite and magnetite), radiation stains, or a high density of absorption defects. Most inclusions in fancy black diamonds are much larger than the voidites in fancy white diamonds and are likely incorporated during rapid growth of the diamond crystal (figure 5, C and D). Unlike fancy white diamonds, the fancy black color can be created in diamonds by several different treatment methods, including heating at high temperatures under vacuum or heavy irradiation treatment. In fact, more than one-third of the black diamonds examined by GIA have been treated.

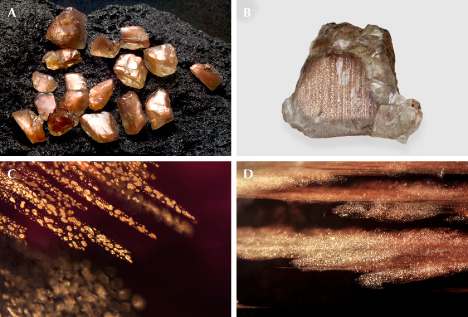

COPPER-COLORED PLAGIOCLASE FELDSPAR

The U.S. state of Oregon is the only confirmed source of natural copper-colored gem feldspar. Ethiopia has been reported as a newer source, which is likely valid given the stones’ consistently different chemistry from that of the Oregon material (Kiefert et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020), but international gemological researchers have not yet visited the deposit to verify its authenticity. All the gem basaltic feldspars from Oregon are sold as “Oregon sunstone” in the gem market, even though not all show aventurescence (figure 6).

Spherical colloidal copper is known to imbue a host material with hues of red, a technique used for centuries to make red glass (Durán et al., 1984; Freestone, 1987; Freestone et al., 2007). The less common green color of Oregon sunstone, however, has long remained an enigma to mineralogists. Metallic copper is electrically conductive and interacts with light quite differently compared to dielectric (insulating) particles, and therefore the interaction cannot be simply approximated with Rayleigh scattering. The free electrons in a copper nanoparticle could resonate with light of certain wavelengths and absorb its energy. These oscillating charges also create a strong electric field on the particle surface and enhance its scattering power. These complicated processes make the color of copper-bearing feldspars unique in the mineral world and challenging to study. Jin et al. (2022a) computed the absorption and scattering properties of spheroidal copper particles of various sizes and shapes embedded in feldspar, which validated the speculation by Hofmeister and Rossman (1983) that an anisotropic colloid is the cause of the strong pleochroism often observed in green-blue Oregon sunstone. The computation shows that the colloidal copper particles are strong and selective absorbers of visible light, and only a few parts per million by weight are sufficient to produce saturated colors in mostly transparent crystals.

The orientation of the copper particles in an Oregon sunstone from the Sunstone Butte mine, evidently controlled by the feldspar structure, has also been characterized in detail using polarized absorption spectroscopy (Jin et al., 2023). Interestingly, the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis by Wang et al. (2025) revealed copper particles elongated along the [001] direction in a dichroic crystal from the same mine, instead of the [100] direction as shown by optical analysis (Jin et al., 2023), suggesting that the feldspar structure may not be the only factor determining the particle shape and orientation. Note that optical analysis reveals the average orientation of all the copper particles collectively, whereas TEM can show only the projection of individual particles one at a time. Wang et al. (2025) oriented the samples crystallographically instead of optically and thus missed the opportunity to correlate the two types of analyses in the same study. More correlated TEM and optical studies are needed to better understand the relationship between the particle shapes and the feldspar structure.

The low (triclinic) symmetry of feldspar leaves its optical orientation unconstrained by its crystallography, resulting in complicated interactions between the highly directional absorption and scattering effects of the copper particles and the anisotropic feldspar optics (Jin et al., 2023). This creates a wide range of possible appearances that are heavily dependent on lighting and viewing directions, presenting more challenges and opportunities for faceting Oregon sunstone than for any other pleochroic gem. Depending on the aspect ratio of the copper particles, Oregon sunstone could be the most pleochroic gem material of all, often showing drastically contrasting colors on different facets of the same stone.

Copper diffusion treatments have been shown to create red and green colors in otherwise colorless feldspar crystals (Emmett and Douthit, 2009; Zhou et al., 2021, 2022), a discovery made after a large amount of red feldspar, purportedly from Asia or Africa, flooded the gem market more than a decade ago, creating controversy in the gem trade regarding the origin and authenticity of these gemstones (Abduriyim, 2009; Abduriyim et al., 2011; Rossman, 2011). The treatment process proves that the particles form by precipitation of copper dissolved in the feldspar lattice. Diffused feldspars generally contain much higher copper concentrations than natural Oregon sunstone (Sun et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2023). The size, shape, density, and zonation of the copper particles also appear noticeably different from diffused and untreated copper-colored feldspars as a result of different thermal histories (Jin et al., 2023). Natural Oregon sunstones typically show much stronger pleochroism than artificially diffused feldspars, likely due to the prolonged cooling in basaltic lava flows compared to the fast heating and cooling processes used in the laboratory.

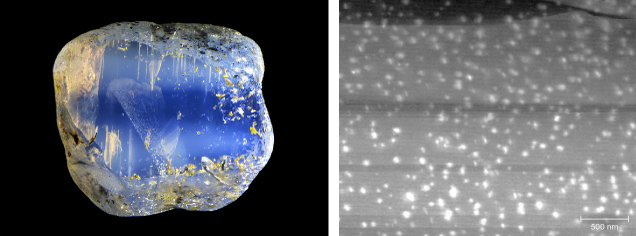

MILKY SAPPHIRE AND RUBY

Corundum (Crn: α-Al2O3) is another gem mineral that can show a milky or cloudy appearance due to nanoscale particle inclusions. Although translucence generally does not increase the attractiveness or value of sapphire or ruby crystals, which ideally are transparent, internal light scattering is often used as a special characteristic to help determine provenance (Palke et al., 2019a,b). Thin milky bands that do not impair the transparency can create an admirable sleepy, velvety appearance, which is best shown in Kashmir sapphires. Some sapphires with a homogeneous milky appearance are marketed as “opalescent sapphires,” which have increased in attraction and popularity in recent years. Most milky sapphires and rubies would display weak asterism if cut into cabochons, but they are more often faceted to enhance their visual transparency. Therefore, they are discussed separately from the star sapphires and rubies in this article due to their special appearance and mineralogy.

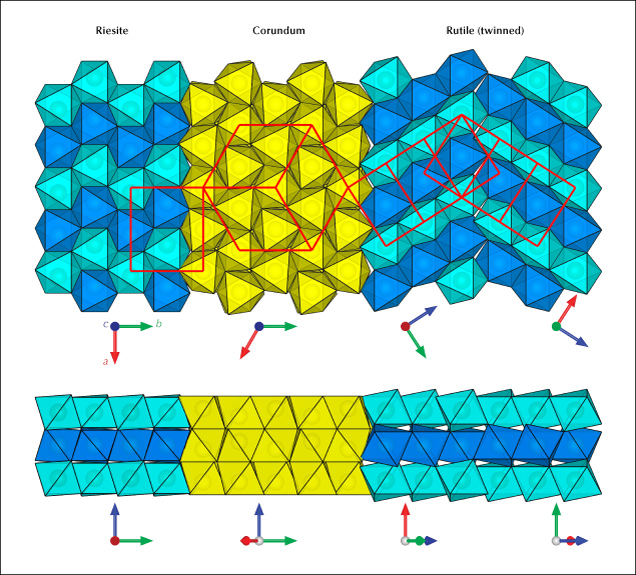

The included milky regions in natural corundum show a positive correlation with the titanium concentration, indicating that the nano-inclusions are most likely titanium-bearing phases. He et al. (2011) systematically studied the evolution of TiO2 precipitates in synthetic titanium-doped sapphire, and their work supports several previous studies of synthetic or heated natural titanium-bearing corundum (Phillips et al., 1980; Jayaram, 1988; Moon and Phillips, 1991; Xiao et al., 1997). Titanium in sapphire would exsolve directly as rutile (Rt: α-TiO2) at 1350°C or higher, yet riesite1 is the initial precipitated phase when annealed at 1300°C or lower, transforming eventually to rutile as the precipitates grow larger.

1Riesite is a high-pressure polymorph of TiO2 with the scrutinyite (α-PbO2) structure. The mineral name was coined only recently (Tschauner et al., 2020), even though the phase had already been known for decades; thus the nomenclature in the literature is often confusing. It has been referred to as srilankite (Ti, Zr oxide with the same structure), TiO2-II, α-PbO2-type TiO2, and even α-TiO2, the last of which is incorrect because α-TiO2 is rutile.

Unfortunately, studies of nano- and micro-inclusions in natural corundum are relatively limited. Shen and Wirth (2012) confirmed the presence of natural riesite precipitates (20–40 nm long and 5–10 nm wide) in the cloudy region of a sapphire from Ilakaka, Madagascar (figure 7). Baldwin et al. (2017) observed high-density nanoparticles (~10–20 nm long) enriched in high field strength elements (HFSEs) in the cloudy brown region of a basaltic sapphire crystal from Petersberg, Germany. Contrary to the authors’ interpretation, the preferred orientations and coherent boundaries shown in the TEM images of these nanoparticles are consistent with solid-state exsolution of HFSEs as riesite precipitates (Jin et al., 2024). Rutile inclusions in corundum crystals have been observed only with much larger sizes (at least 200 nm long) (Phillips et al., 1980; Moon and Phillips, 1991; Xiao et al., 1997; He et al., 2011). A recent atom probe tomography (APT) and TEM study reported an unknown phase of secondary beryllium-bearing nanoparticles (~10 nm) occurring together with riesite precipitates (~5 nm) in a Nigerian sapphire crystal containing high concentrations of heavy HFSEs and beryllium (Jin et al., 2024). A similar study of a Madagascar sapphire containing less beryllium showed only riesite precipitates (~20 nm), with beryllium concentrated at the boundary between the nanoparticles and the corundum matrix (Emori et al., 2024). Riesite is stable at pressures above 6 GPa (Olsen et al., 1999), which is much greater than the pressures associated with the growth conditions of most gem corundum (Giuliani et al., 2014). This suggests that all the riesite nano-inclusions in corundum form through solid-state exsolution, stabilized by the immense strain induced by the coherent boundary between riesite and corundum (Xiao et al., 1997; He et al., 2011).

Most (if not all) of these nano-inclusions in natural corundum contain titanium, which would dissolve into the corundum lattice under high-temperature heat treatment, turning the stones bluer due to the newly formed titanium-iron pairs. In fact, the milky or cloudy appearance is commonly used by gem miners and traders to determine whether natural corundum may be color enhanced by heat treatment, with the geuda-type sapphire from Sri Lanka the best-known example (Gunaratne, 1981; Ediriweera et al., 1989; Perera et al., 1991).

Submicron and nanoscale inclusions are quite common in natural materials, as suggested by the few studies on sapphire and feldspar. Even though most of the nano-inclusions are optically invisible and may not affect the appearance of minerals and gemstones, they are of great importance for geological research, as they contain detailed information about the mineral’s geological history that cannot be retrieved otherwise. More careful TEM and APT analysis of natural corundum and other minerals is needed to fully understand the nature of these nano-inclusions. More unknown phases likely are waiting to be discovered as new mineral species in these nano-inclusions.

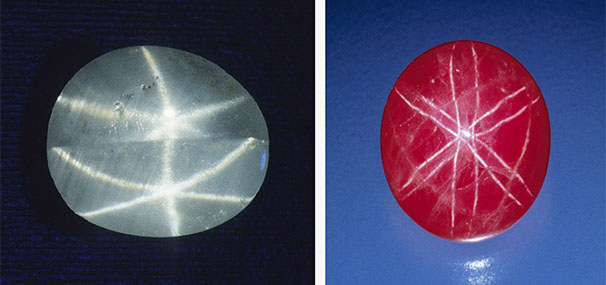

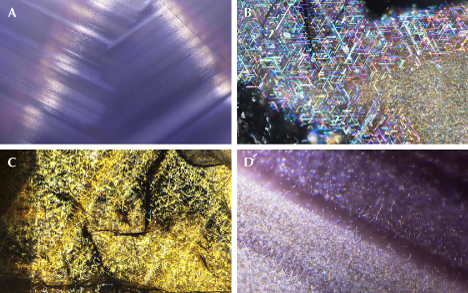

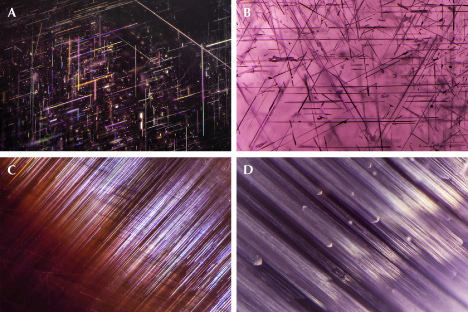

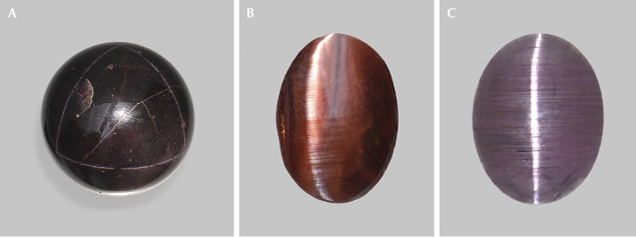

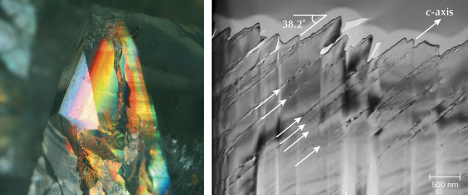

STAR SAPPHIRE AND RUBY

Star sapphire and ruby are certainly the most popular asteriated gemstones (box D) and probably the best-known of all phenomenal gemstones. The asterism in star sapphire and ruby is created by thin needle-shaped inclusions known as “silk” in the corundum host (figure 8). It has long been speculated that these silk inclusions are rutile needles. However, prior to TEM or micro-Raman spectroscopy, only circumstantial evidence of rutile could be found, such as the presence of titanium in the bulk composition as well as the high refractive index (RI) and brownish colors. Nassau (1968) suspected that the needles were tialite (Al2TiO5) due to the apparently lower symmetry but could not provide any evidence for this identification. Tialite is a synthetic material only stable at temperatures above ~1300°C and is thus unlikely to be found in any natural corundum, which generally forms at lower temperatures (Giuliani et al., 2014). The presence of rutile in synthetic star sapphire was first confirmed by Frondel (1954) by chemical and XRD tests on crushed and centrifugation-separated precipitates. The first direct observation of rutile needles in synthetic sapphire using TEM was done by Phillips et al. (1980) nearly three decades later. Viti and Ferrari (2006) reported a “monoclinic polymorph of TiO2” in a Verneuil-grown star sapphire, although the TEM images and the electron diffraction patterns clearly show a twinned rutile structure. The behavior of titanium in synthetic titanium-doped corundum is relatively well understood after the study by He et al. (2011) showed only two types of titanium-containing precipitates, riesite and rutile, depending on the annealing temperature and time.

Similar to nanoprecipitates, needle inclusions in natural corundum are significantly understudied. Moon and Phillips (1984b) first applied TEM to natural black (star) Australian sapphire and surprisingly discovered hematite (Hem: α-Fe2O3) and/or ilmenite (Ilm: FeTiO3) as the star-creating needles, instead of rutile, supporting an earlier claim by Weibel and Wessicken (1981) on a Thai black star sapphire with no detectable titanium. The authors also reported that rutile was observed in blue and blue-green stones from Australia but did not publish the data. Needle-shaped hematite/ilmenite inclusions have been reported multiple times as the star-forming silk since the original discovery (Saminpanya, 2001; Izokh et al., 2010; Khamloet et al., 2014; Bui et al., 2015, 2017; Soonthorntantikul et al., 2017; Sorokina et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022), including almost pure hematite in a titanium-free corundum from Shandong, China (Zhao et al., 2022). On the other hand, despite mounting circumstantial evidence for the rutile needle inclusions in natural corundum, it was not until recently that direct confirmation using electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) was first reported (Palke and Breeding, 2017). It appears that ilmenite and/or hematite inclusions are more common than rutile as the star-forming needles in corundum, which makes sense as natural corundum contains much more iron than titanium. However, there could also be a bias caused by rutile needles being generally smaller and harder to identify. As the studies on this subject are very limited, it is not possible to estimate the percentage of each type of inclusion in natural corundum.

![Figure 9. Left: [001]<sub>Crn</sub> ([100]<sub>Rt</sub>) zone axis darkfield TEM image showing needle-shaped and heart-shaped twinned rutile precipitates in titanium-doped synthetic sapphire annealed at 1300°C for 50 hours. The selected area electron diffraction patterns of the two precipitates are shown as insets. Right: [210]<sub>Crn</sub> ([011]<sub>Rt</sub>) zone axis high-resolution TEM image showing the (110)<sub>Crn</sub>//(011)<sub>Rt</sub> interface with periodic dislocations (white arrows) to accommodate the lattice mismatch between rutile and corundum crystal structures. Images from He et al. (2011).](https://www.gia.edu/images/SU25-Jin-Fig9AB-332260-636px.jpg)

TEM analyses show the ilmenite/hematite inclusions are elongated along the ⟨100⟩ direction (ilmenite and hematite have the same crystallographic orientation as corundum as they are isostructural) (Moon and Phillips, 1984b; Zhao et al., 2022), whereas the rutile needles are elongated along ⟨011⟩RtII;⟨210⟩Crn, with {100}RtII;{001}Crn (figures 9 and 10) (Phillips et al., 1980; Jayaram, 1988; Moon and Phillips, 1991; Xiao et al., 1997; Viti and Ferrari, 2006; He et al., 2011). Therefore, the needles perpendicular to the growth zoning of corundum are ilmenite or hematite, whereas those parallel to the growth zoning are rutile (figure 11). Mayerson (2001) incorrectly claimed that all stars in untreated natural sapphire are parallel to the growth zoning, and thus mistakenly concluded that stars with rays perpendicular to growth zoning can be an indication of titanium-diffused star sapphire. When needles of both orientations are present in the same corundum crystal, a rare 12-rayed star can be observed (again, see figure 1, top left). The two sets of 6 rays in a 12-rayed star may show different colors (Vertriest and Bruce-Lockhart, 2018), as rutile silk mostly appears silver white (figure 8A) and hematite/ilmenite silk can appear golden yellow depending on the iron content (figure 8, C and D). It should be noted that Bui et al. (2017) claimed that only ilmenite inclusions could be found in a 12-rayed star sapphire likely from Sri Lanka, although the Raman spectra presented in their paper do not conclusively exclude the presence of rutile.

Iron and titanium are among the most common trace elements in natural corundum, which is why it is generally believed that these needle inclusions form by solid-state precipitation of iron and/or titanium dissolved in the corundum structure. Natural rutile silk has the same crystallographic orientation relation (COR) as synthetic or titanium-diffused star sapphire, suggesting a similar formation mechanism. Little is known about the formation mechanism of the ilmenite/hematite needles, as heating an iron-rich corundum failed to produce any similar precipitates (Moon and Phillips, 1991). Iron is much more soluble in corundum than titanium and probably would not precipitate unless annealed at significantly lower temperatures for much longer periods than in the study by Moon and Phillips (1991), and exsolution may be achievable only in natural geological settings.

It should be noted that experiments of epitactic growth of rutile (Gao et al., 1992) and hematite (Wang et al., 2002) on a corundum substrate can also create coherent or semi-coherent interfaces similar to those observed for the needles exsolved in the corundum matrix (He et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2022). Palke and Breeding (2017) first argued for epitactic coprecipitation of the oriented needle rutile inclusions containing heavy HFSEs, based on observations of glassy melt inclusions that indicate fast cooling, as well as the assumption that the heavy HFSEs are strongly incompatible and thus unlikely to be incorporated into the corundum lattice during crystal growth. However, this argument has been invalidated by a recent APT study showing that significant amounts of heavy HFSEs (e.g., tungsten, niobium, and tantalum) can not only be dissolved into the crystal structure of natural corundum but are also likely to be enriched beyond their solubility in corundum due to preferred adsorption on the growth surfaces (Jin et al., 2024). This means that the precipitation of HFSEs could occur when the already supersaturated host corundum is heated above its formation temperature, which would be a much faster process than previously thought.

Moreover, the distribution of rutile silk in natural corundum mostly correlates with fluctuating titanium concentrations associated with the hexagonal {110} growth zoning, yet the basal {001}Crn//{100}Rt interfaces of the needle inclusions are always wider than the vertical {110}Crn//{011}Rt interfaces, as evidenced by the much stronger reflection seen on the {001}Crn surface (again, see figure 8, A and B). These observations are hard to reconcile with the epitactic coprecipitation mechanism, because if the epitaxy occurs on the basal {001}Crn surface, as suggested by the platy needle shape, its distribution should not correlate with the {110} growth zoning.

The precipitation of rutile (or other iron/titanium oxide) from corundum should result in a rim deprived of titanium (and/or iron) immediately around the precipitation, a texture that in theory could be used to test the formation mechanism of the needle inclusions. Unfortunately, such small variations at the nanometer scale are difficult to detect using current techniques, and the compositional gradient may have been erased by diffusion in any natural corundum. The nanoscale polysynthetic twinning of rutile needle inclusions (figure 9) (He, 2006; Viti and Ferrari, 2006) is also likely to be exclusive to solid-state exsolution as a mechanism to redistribute the strain, since similar structures have not been reported in epitactically coprecipitated rutiles (Gao et al., 1992). It is not clear, however, how such nanoscopic twinning would be preserved in natural corundum over geological timescales.

CAT’S-EYE AND STAR CHRYSOBERYL

Cat’s-eye chrysoberyl is the most recognized and most valuable chatoyant gemstone, especially if it is accompanied by a color change (cat’s-eye alexandrite; figure 12A). In fact, the term cat’s-eye refers to chatoyant chrysoberyl by default if the mineral species is not specified. Chrysoberyl (Cbrl: BeAl2O4) is a beryllium aluminate mineral that crystallizes in an olivine-type structure, with hexagonal close-packed (HCP) oxygen atoms positioned as in the corundum and hematite structures. The cation arrangement in the chrysoberyl structure, with half of the octahedral sites filled by aluminum and one-eighth of the tetrahedral sites filled by beryllium, results in a pseudohexagonal orthorhombic symmetry. The chrysoberyl structure has been reported in many different crystallographic axis settings, making it difficult to compare the orientation notations across the literature. The Pmnb (a = 5.48 Å, b = 9.42 Å, c = 4.43 Å) setting will be used in this article because it intuitively keeps the HCP stacked layers parallel to (001), making it easy to compare different close-packed structures (Drev et al., 2015). The Miller indices cited in the literature using other settings will be translated to the Pmnb setting.

Despite its long history as a prominent phenomenal gemstone, there had not been any serious investigation into the details of needle inclusions in chrysoberyl until recently. By using a combination of optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and Raman spectroscopy, Schmetzer et al. (2016) conducted a comprehensive survey of included chrysoberyl from different locations and showed that almost all needle inclusions in natural chrysoberyl are rutile, with the only exception of ilmenite needles found in a four-rayed star chrysoberyl from Sri Lanka. The oriented needle inclusions presumably form by precipitation of titanium originally dissolved in the chrysoberyl structure. Elongated cavities or channels may also exist along the same orientations as the rutile needles.

Three different needle orientations have been observed in chrysoberyl, elongated along the [100]Cbrl, ⟨110⟩Cbrl, and [001]Cbrl axes. The [100]Cbrl needles sometimes occur together with ⟨110⟩Cbrl needles, forming a pseudohexagonal array at a ~60° angle relative to one another. The ⟨110⟩Cbrl needles are often connected as twinned pairs to form a V shape, a heart shape, or a triangle, depending on needle width. Ilmenite needles are reported to occur only along the [100]Cbrl axis. No TEM analysis has been done on the needle inclusions parallel to the (001)Cbrl plane, but they most likely have an orientation similar to the rutile needles found in star sapphire in light of their similar HCP structures. The only atomic-resolution TEM study of the rutile precipitates in chrysoberyl, conducted on a twinned sample from Bahia, Brazil, showed a COR of {013}Rt//{120}Cbrl + ⟨100⟩RtII⟨001⟩Cbrl, which corresponds to the needles and striped plates elongated along the [001] axis of chrysoberyl with L-shaped or zigzag cross sections observed by Schmetzer et al. (2016). It should be noted that these inclusions are quite unusual because they are elongated perpendicular to the stacked oxygen layers in the structure, rather than parallel to them.

Depending on the dominant needle orientation and the cut of the material, chrysoberyl can display chatoyancy or asterism with up to six rays (figure 12). It is not clear what process controls the orientation of the needle inclusions in chrysoberyl, but the temperature at which the titanium oxide starts precipitating out may play an important role. Synthetic cat’s-eye and star chrysoberyl can be produced by growing Ti3+-doped crystals in neutral or reducing atmospheres and then annealing in an oxygen atmosphere to precipitate TiO2. Only needles parallel to the (001)Cbrl plane have been observed in synthetic chrysoberyl (Schmetzer and Hodgkinson, 2011; Schmetzer et al., 2013, 2016). Titanium diffusion, as used to create artificial stars in sapphire, can also create chatoyancy in chrysoberyl. Another method, which uses a floating zone technique to create cat’s-eye alexandrite with tubular fluid inclusions, has been patented by the Seiko Epson Corporation in Japan (Schmetzer et al., 2013).

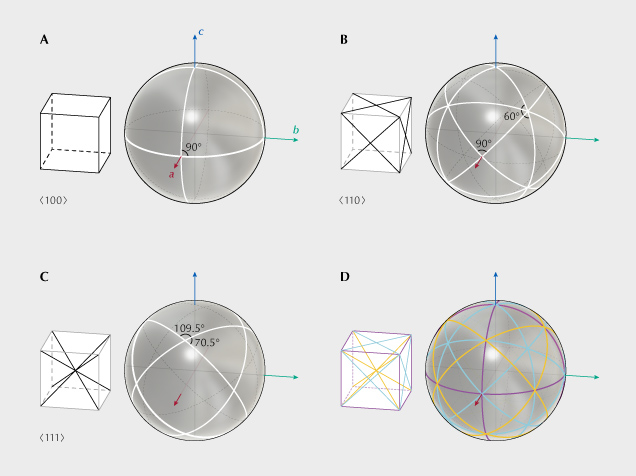

STAR GARNET

Silicate garnet (Grt: X2+3 Y3+2 [SiO4]3) is a mineral group with one of the highest possible symmetries in three-dimensional space (space group 230, the last space group). The cubic symmetry allows the needle inclusions to be arranged in three dimensions, instead of coplanar as in corundum (figure 13). As a result, the bright lines constructing the asterism cannot all intersect at one point, which means multiple stars may be seen on a single garnet crystal. The best shape to demonstrate this “star network” is a sphere, as is commonly used when cutting a star garnet. Depending on the orientations of the needle inclusions, different asterism patterns may be observed on a polished spherical garnet crystal (figure 14). Therefore, the angles between the rays of the stars can be used to identify the orientations of the inclusions (Walcott, 1937; Kumaratilake, 1998; Schmetzer and Bernhardt, 2002; Schmetzer et al., 2002). Sometimes two different sets of inclusions can appear in the same garnet crystal, creating more complicated networks of stars (Guinel and Norton, 2006). Similar asterism patterns, although much rarer, can sometimes be observed in spinel crystals, which also belong to the cubic crystal system (Walcott, 1937; Schmetzer, 1988; Kumaratilake, 1998; Schmetzer et al., 2000; Promwongnan et al., 2017; Hughes, 2018).

While rutile is the most common needle inclusion in garnet, other oriented inclusions such as ilmenite, magnetite, corundum, apatite, quartz, mica, olivine, pyroxene, and amphibole have also been observed (van Roermund et al., 2000; Hwang et al., 2010, 2013; Zhang et al., 2011; Ague and Eckert, 2012; Axler and Ague, 2015; Xu and Wu, 2017; Keller and Ague, 2019, 2020). However, the relation between asterism and inclusions other than rutile needles has yet to be confirmed. Most rutile needles are elongated along the ⟨111⟩ directions of garnet, creating four-rayed stars intersecting at ~70°/110° angles (figures 14C and 15A; video 2). Rutile needles elongated along the ⟨001⟩Grt directions have also been reported (Hwang et al., 2015), producing asymmetric six-rayed stars with ~70°/55°/55° angles together with the ⟨111⟩Grt needles.2 Although specific CORs between the rutile needles and the garnet host are commonly observed in TEM and EBSD analyses of star garnet, such as {100}Rt//{134}Grt + ⟨013⟩RtII⟨111⟩Grt or {100}RtII{011}Grt + ⟨011⟩RtII⟨100⟩Grt (Keller and Ague, 2022), many of the ⟨111⟩Grt needles show nonspecific or “statistical” CORs, with [001]Rt falling onto a cone of 28.5°±2.5° around ⟨111⟩Grt (Keller and Ague, 2019).

2The ⟨011⟩Grt needle orientation reported by Guinel and Norton (2006) is an error and should be ⟨001⟩Grt instead.

Most star garnets are in the almandine-pyrope-spessartine (Fe3Al2Si3O12–Mg3Al2Si3O12–Mn3Al2Si3O12) solid-solution series that form under high-pressure conditions deep in the earth. Due to its stability over a wide range of temperature and pressure conditions, garnet is an important indicator of evolving metamorphic conditions and underlying tectonic processes, and it has been studied extensively by metamorphic petrologists. Consequently, the formation mechanism of the needle inclusions is essential for the correct interpretation of the garnets’ chemical data, which is why the CORs of the needles in garnet have drawn a lot of attention in the past decade. The complex crystal structure and chemistry of garnet, and the accordingly more diverse CORs of the needle inclusions, make this already controversial subject even more convoluted. As a result of the more complicated chemical reactions and structure-matching schemes, many different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the formation process of these needle inclusions, including solid-state precipitation, interface-coupled dissolution-reprecipitation, and epitactic co-growth or overgrowth. Proyer et al. (2013) as well as Keller and Ague (2019) discussed all hypotheses in detail and concluded that (open-system) solid-state precipitation (exsolution) is the only process that withstands scrutiny. Other hypotheses either contradict observations or lack key supporting evidence. This conclusion is further supported by the successful prediction of CORs using an edge-to-edge matching model (Keller and Ague, 2022).

It should be noted that the asymmetrically oriented rutile needles intersecting the growth zones at steep angles (e.g., figure 13, C and D) are harder to explain by solid-state precipitation, which led to the interpretation of epitactic nucleation and co-growth (Griffiths et al., 2020). Precipitation within the crystal should fully observe the symmetry of the host mineral, whereas crystallization is one-dimensional along the growth surface, which reduces the local symmetry. However, as pointed out by Keller and Ague (2019), preexisting crystallographic defects, chemical gradients, as well as varying lattice parameters might also promote preferred precipitations along certain directions. Nonetheless, these parallel needles could create chatoyancy instead of asterism in the occasionally reported cat’s-eye garnet (figures 13C and 15B). Similar linear features can also be found in cat’s-eye spinel (figures 13D and 15C).

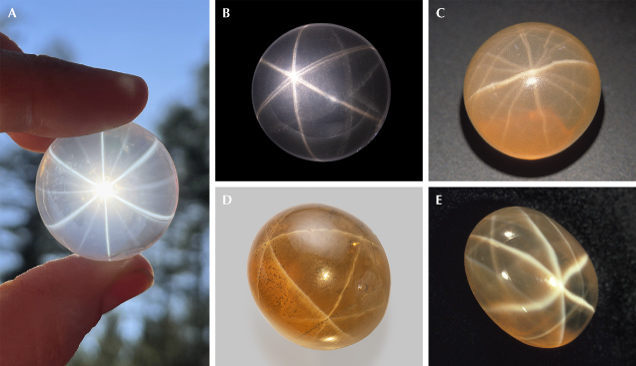

STAR QUARTZ

Although rutile is the most common needle-like inclusion in quartz (Qz: α-SiO2) and can create poor-quality asterism or chatoyancy with a strange shape (Johnson and McClure, 1997; Schmetzer and Steinbach, 2022, 2023; Gauthier et al., 2023), the high-quality stars observed in quartz are not related to titanium oxide. These star quartzes are only found as turbid massive quartz and never as clear euhedral quartz crystals (Goreva et al., 2001; White, 2015), although there may be a sampling bias because only massive anhedral quartz would be cut into cabochons or spheres to display the asterism. Most star quartz has pink color that varies from bright to pale; thus, it is called rose quartz. This name is sometimes also applied to euhedral pink quartz crystals, the color of which is photochemically unstable and can be bleached away easily with UV light or low heat. The pink color of massive star rose quartz, on the other hand, is stable up to ~575°C, indicating a completely different coloring mechanism.

Sillimanite (Sil: Al2SiO5) was first identified using TEM as the needle inclusions in a star quartz from the Ratnapura district, Sri Lanka (Woensdregt et al., 1980), elongated along ⟨001⟩SilII⟨100⟩Qz, with {110}SilII{001}Qz. Dumortierite (Dum: Al7Si3BO18) was also identified as the fibrous residue observed after rose quartz was dissolved in hydrofluoric acid (Applin and Hicks, 1987; Ignatov et al., 1990; Goreva et al., 2001). Further study revealed that these dumortierite inclusions contain significant amounts of iron and titanium, and they show a superlattice structure likely due to cation ordering (Ma et al., 2002). The pink color of rose quartz turned out to result from the iron-titanium intervalence charge transfer in these nano-inclusions. It should be noted that the earlier reports of rutile nanoneedles in rose quartz (von Vultée, 1955, 1956; Eppler, 1958) were most likely incorrect, as none of the 29 rose quartz samples from different locations analyzed by Goreva et al. (2001) showed any evidence of rutile. Regrettably, the COR between these dumortierite needles and the quartz host is unknown, as all analyses were performed on residue fibers with all the quartz dissolved away.

The silicate needle inclusions, most likely formed by solid-state exsolution (Ma et al., 2002), have low RIs that are close to those of the quartz host, resulting in much weaker scattering power compared to the strongly refractive rutile or iron oxide inclusions in other gemstones. Therefore, star quartz has a more transparent appearance than star corundum or garnet. The star in rose quartz is often more strongly observed using light transmitted through the stone, an effect known as “diasterism” (figure 16A) (Killingback, 2006), whereas only “epiasterism” under reflected light can be observed in most other asteriated gemstones.

Some rose quartz crystals display 12-rayed stars, indicating two sets of needle inclusions with different crystallographic orientations (figure 16, A and C). It is possible that the two orientations are from different mineral inclusions, as both dumortierite and boron-bearing sillimanite were found as needles in a rose quartz from Brazil (Ma et al., 2002). Needle inclusions elongated off the (001) plane are also occasionally observed in quartz (Johnson and Koivula, 1999; Schmetzer and Glas, 2003), creating complex star networks in sphere-cut crystals similar to star garnet (figure 16, D and E; video 3). Chatoyancy is also very rarely observed in quartz (Choudhary and Vyas, 2009; Choudhary, 2011), indicating needle inclusions elongated parallel to the c-axis. Unfortunately, the nature of these abnormally oriented needles is not clear.

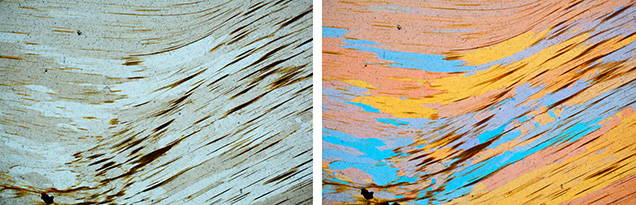

TIGER’S-EYE AND PIETERSITE

Tiger’s-eye is a chatoyant variety of quartz containing altered amphibole needle inclusions (figure 17, A and B). Unlike the other star or chatoyant gemstones in which the host is a single crystal, tiger’s-eye consists of columnar polycrystalline quartz crystals that are 0.1–1.0 mm in diameter and 1–10 mm in length (Heaney and Fisher, 2003). As indicated by its orientation, the chatoyancy of tiger’s-eye is created by fibrous mineral inclusions and not the columnar quartz crystals (figure 18). No special COR has been observed between the needle inclusions and the quartz crystals, suggesting that the aligned needle orientation must be controlled by crystal growth. The typical golden-brown color is caused by the iron-rich amphibole needles being weathered to iron (hydr)oxides. In the less common dark blue variety, commonly known as hawk’s-eye (or falcon’s-eye) (figure 17C), the amphibole needles are less altered and retain their original color.

Tiger’s-eye has long been attributed to pseudomorphism with quartz replacing crocidolite, a blue asbestiform variety of the sodic amphibole riebeckite (Rbk: Na2Fe5Si8O22(OH)2) (Wibel, 1873). However, Heaney and Fisher (2003) proposed that quartz and riebeckite grew synchronously through an episodic crack-seal mechanism, as optical and electron microscopic observations failed to show any evidence for pseudomorphism.

Pietersite, reportedly found only in Namibia and China, is generally described as a brecciated variety of tiger’s-eye (figure 17D). Although the chatoyancy is also caused by crocidolite fibers, the silica that composes pietersite is in the form of chalcedony (discussed later in the section on iridescent agate) instead of columnar quartz. The chaotic texture of pietersite also indicates a formation mechanism different from that of tiger’s-eye. Instead of pseudomorphism or a crack-seal mechanism, pietersite specimens are theorized to have formed as solution breccias, in which the crocidolite fibers form by late-stage reactions between chalcedony and hematite in a sodic fluid (Hu and Heaney, 2010).

OTHER ASTERIATED AND CHATOYANT STONES

Needle-like inclusions, which are the most common inclusion habits, can be found in almost any included mineral. The shape of an inclusion is often controlled by the lattice match across the boundary between the included mineral and the host, as demonstrated by the examples discussed above. A needle inclusion requires only a near-perfect lattice match along one dimension, with the interfaces along the other two dimensions restrained to a very small scale by strain. Many defects generated during crystal growth or dissolution, such as growth tubes and etch channels, also have an oriented linear form, which may scatter light analogously to needle inclusions. In addition, some minerals—such as actinolite, hypersthene, sillimanite, and chrysotile—naturally adopt a columnar or fibrous habit similar to that observed in tiger’s-eye. Therefore, chatoyancy and asterism may be observed in almost any mineral host included with fibrous minerals or defects (figure 19). Even diamond has been reported to show asterism (Watts, 2021). There have been attempts to list all the gemstones that are reported to display asterism or chatoyancy (Kumaratilake, 1997; Steinbach, 2016, 2018), which will not be repeated here. Because the star and cat’s-eye effects can only be observed in a cabochon cut, it is highly probable that many chatoyant and asteriated minerals have not been discovered simply because no one has cut and polished them into a curved shape. In fact, many of the reported stars and cat’s-eyes in gemstones are so weak that they are only observable under strong fiber-optic light, which may attract the attention of niche collectors, but probably would not be an eye-catcher in the general gem market. The columnar or fibrous texture is also easy to fabricate in glass and plastic by simply pulling and fusing together a bundle of optical fiber. Therefore, chatoyant glass (figure 19A, left) and plastic are very affordable imitations of cat’s-eye gemstones of any color. Nonetheless, there is yet to be a convincing glass or plastic milky regions in natural corundum show a positive correlation imitation for asterism, as the crystallographic symmetry is necessary to force the fibers into multiple directions.

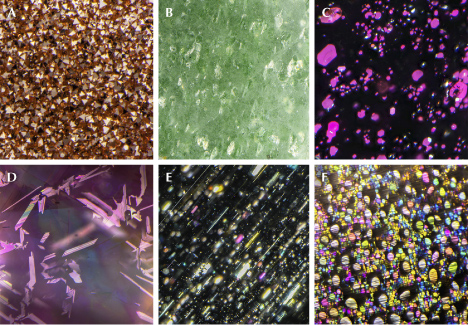

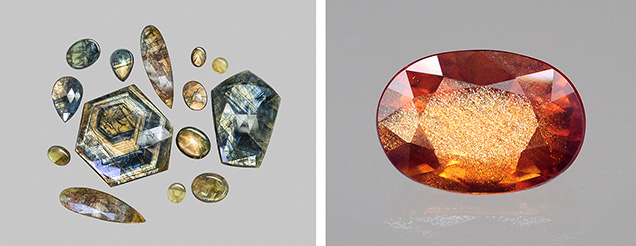

AVENTURESCENCE IN GEMSTONES

The word aventurine derives from a ventura in Italian, meaning “by chance,” originating from the glittering glass “avventurina,” now known as “aventurine glass” or “goldstone” (figure 20A), which was allegedly invented by accident in eighteenth-century Italy (Moretti et al., 2013). The name was first adopted in mineralogy for quartzite (a metamorphic rock predominantly composed of polycrystalline quartz) containing glimmering mica crystals (figure 20B), although the best-known aventurescent mineral is aventurine feldspar. The term aventurescence is now used to describe the glittering effect created by isolated and visually discernible flat interfaces scattered in any transparent to translucent gemstone. Most aventurescence in gemstones is caused by oriented inclusions, and would appear as a sudden intense reflection (box E) that occurs only in certain directions, commonly known as schiller (Colony, 1935).

It should be noted that although less abundant than needle inclusions, flaky or thin-film inclusions are not uncommon in minerals (e.g., figure 20, C–F). Indeed, inclusions of any shape may have flat facets that reflect light. Almost all needles discussed above have a rectangular cross section with flat surfaces when examined with an electron microscope, which means light will be scattered preferentially perpendicular to the flat surfaces and create a schiller or sheen effect. The straight edges of some film inclusions, on the other hand, can also scatter light more randomly like a needle, creating chatoyancy or asterism in a cabochon-cut stone. It is not unusual for inclusions in a stone to vary in size and shape. As a result, the appearance of a stone, or the phenomenon it displays, depends greatly on how it is cut and polished.

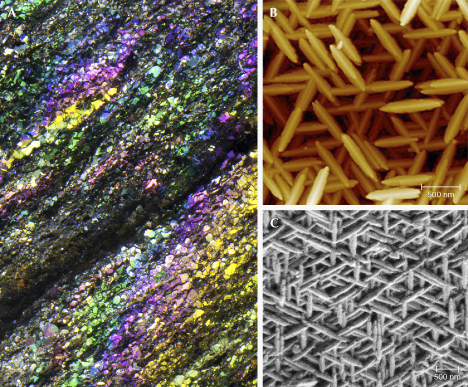

COPPER SUNSTONE

Gem-quality aventurine feldspars are typically known as “sunstones” (Andersen, 1915), with mainly two types of reflective inclusions found in nature: metallic copper and iron oxides. Copper platelet inclusions in feldspars are rare and only have been reported in feldspar phenocrysts in certain basalts, as in the well-known Oregon sunstone. Similar material has also been reported from Ethiopia, but it shows a chemistry distinct from that of Oregon sunstone (Kiefert et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020). The copper platelets are oriented along the cleavage planes of feldspar, mostly the (010) plane and less commonly the (001) plane (Farfan and Xu, 2008; Xu et al., 2017). Because the copper platelets are completely opaque, the color of the schiller arises only from the light reflected by the copper particles, which is reddish brown (figure 21). Copper sunstones may contain colloidal copper particles in addition to the platelets, resulting in red or blue-green bodycolors underneath the schiller (again, see figure 1, second from left in bottom row). As mentioned earlier, copper is known to diffuse quickly in feldspar crystals, which may be why the relatively fast cooling in volcanic rocks is necessary for them to precipitate as metallic particles instead of diffusing out of the crystal as the solubility of copper decreases in the feldspar. Nonetheless, the cooling rate of sunstone-bearing basaltic rocks is still much slower than in any experiments in a laboratory. It may take months to years for the basaltic lava to cool down from the melting temperature. This is why copper sunstone showing strong aventurescence has yet to be created in a laboratory, even though red and green colors have been produced relatively easily from copper diffusion (Jin et al., 2023).

HEMATITE SUNSTONE

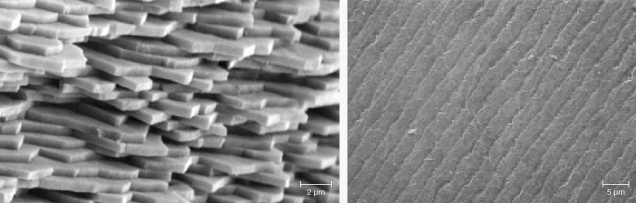

Hematite sunstones are mostly found in granites or pegmatites and can be generally divided into two categories: orthoclase and sodic plagioclase (oligoclase or albite). They typically can be easily distinguished by the shape and orientation of the hematite films. Sodic sunstone, mostly oligoclase, such as the most studied examples from Tvedestrand, Norway (Andersen, 1915; Divljan, 1960; Neumann and Christie, 1962; Kraeft and Saalfeld, 1967; Copley and Gay, 1978, 1979, 1982), contains rectangular and hexagonal hematite plates along the (112), (112), (150), and (150) planes. Due to the triclinic symmetry of plagioclase feldspar, the hematite plates are oriented askew relative to the cleavage planes (figure 22, A, D, and E). Orthoclase sunstones, such as those from Tanzania (Hänni et al., 2003) and Australia (Koivula and Kammerling, 1989), on the other hand, tend to have long hematite blades parallel to the (100) plane and extended along the [010] or ⟨011⟩ directions of the feldspar (figure 22, B, C, F, and G), which are always symmetrical around the cleavage planes (Jin et al., 2022b). These elongated inclusions often create chatoyancy or asterism when cut into a cabochon (Hyrsl, 2001; Hänni et al., 2003). Smaller hexagonal or triangular flakes parallel to the (100) and (102) planes are also common in lower-quality orthoclase sunstones (Liu et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2022b).

![Figure 22. A: A 42.50 ct rough oligoclase sunstone reportedly from Tanzania. B: An 18.40 ct “meteor shower sunstone” cabochon from Tanzania. C: A 14.77 ct round orthoclase sunstone cabochon from Tanzania showing a four-rayed star. D: Iridescent reflection from hematite inclusions in a Canadian labradorite due to thin-film interference. E: Hematite platelets in an oligoclase “confetti sunstone” from Tanzania; courtesy of John I. Koivula. F: Thin-film magnetite and hematite blades elongated along the ⟨011⟩ directions in an orthoclase rainbow lattice sunstone from Australia. G: Thin-film iridescent hematite blades elongated along the [010] directions in an orthoclase sunstone from Tanzania, along with some tiny needles along the ⟨011⟩ directions. Photos by Emily Lane (A), Annie Haynes (B), Maha Tannous (C), Shiyun Jin (D), and Nathan Renfro (E, F, and G); fields of view 2.2 mm (D), 9.56 mm (E), 6.39 mm (F), and 7.20 mm (G).](https://www.gia.edu/images/SU25-Jin-Fig22A-G-332263-636px.jpg)

Unlike the metallic black color of large hematite crystals, the hematite film inclusions in sunstones are transparent with orange to deep red colors depending on their thicknesses, yielding what appears to be an orange to red bodycolor. The transparent hematite flakes in sunstones are sometimes misidentified as biotite by those who are not familiar with their transparent appearance (Lee and Parsons, 2015). The thinner hematite inclusions can also create iridescent colors due to thin-film interference (figure 22, D–G), primarily observable only with an optical microscope.

The process that creates the hematite flakes in sunstones takes much longer than the process that creates the copper platelets, as indicated by the different types of rocks they are found in. The mechanism that produces the hematite flakes is still not well understood, with several hypotheses proposed over the past two centuries (Smith and Brown, 1988, pp. 638–639). Simultaneous crystallization was the first to be rejected because hematite flakes are not oriented along the common growth faces of feldspar (Andersen, 1915). Precipitation of iron from the feldspar lattice is the simplest theory, but this explanation poses the question of why some feldspars with exceptionally high iron content remain hematite-free. Another hypothesis is that reaction with the surrounding fluid introduces iron into the feldspar crystals, but it does not explain how the imported iron is transported and precipitated as hematite flakes inside the feldspar. A recent study of rainbow lattice sunstone from central Australia showed that the hematite films in orthoclase sunstone were originally magnetite (Mag: Fe3O4) films that were oxidized at a later stage (Jin et al., 2022b). Rainbow lattice sunstone is a unique sunstone with exceptionally large magnetite and hematite “blades,” creating a rainbow lattice effect resulting from the thin-film interference of light reflected by hematite films (figure 22F). Only the thinner parts of the magnetite films have been oxidized to hematite, showing light yellow to orange colors in transmitted light and pink to blue iridescence under reflected light. The magnetite films, crosscutting the plagioclase lamellae exsolved from the orthoclase matrix, clearly represent precipitation of iron dissolved in the feldspar lattice, likely due to decreasing oxygen fugacity. The orientation of the magnetite films, like the other oriented precipitates in mineral crystals such as star sapphire, is a result of minimization of the surface energy by finding the interface with the best lattice match. The same mechanism should apply to other orthoclase sunstones, such as those from Tanzania and the United States (North Carolina) (Hänni et al., 2003; Choudhary, 2008; Challener et al., 2017), based on the similar appearance and orientation of the hematite films. The only difference is that all of the precipitated magnetite films in the other orthoclase sunstones have been oxidized to hematite due to their smaller and thinner sizes. However, it is not clear whether this process can be expanded to the sodic plagioclase sunstones, as those hematite flakes are typically thicker (darker red color with less iridescence) with more pristine hexagonal forms.

CLOUDED FELDSPAR

Although only a small proportion of included feldspars qualify as sunstones, crystallographically oriented needle-like iron oxide inclusions are almost ubiquitous in plutonic and metamorphic plagioclase feldspars (e.g., figure 23A). Feldspars containing dense iron oxide needles, also known as clouded feldspars (Smith and Brown, 1988, p. 639), display black, dark gray, or brown colors with an almost opaque appearance. A silver (or less commonly golden) sheen can often be observed on the polished surfaces of these clouded feldspars, which makes their host gabbro or anorthosite rocks popular countertop materials (figure 23, B and C). When cut into cabochons, clouded feldspar can display a cat’s-eye (or star) effect as expected (figure 23D). However, cat’s-eye (or star) plagioclase feldspars rarely appear in the gem market, mostly because the quality of the chatoyancy or asterism is generally not attractive enough by itself to be worth the cost of careful cutting and polishing.

Due to their geological importance in the study of magmatic and metamorphic processes, as well as the historical evolution of Earth’s magnetic field, the needle inclusions in plagioclase feldspar have been studied extensively compared to the other oriented inclusions found in minerals, providing important insights into how they formed. Combining optical microscopy, EBSD, and TEM analysis has revealed multiple types of magnetite needles with different CORs to the host feldspars (Bian et al., 2023 and references therein). Most observations suggest that these needles form by precipitation of iron that was originally dissolved in the feldspar structure, perhaps due to interaction with a reducing fluid (Bian et al., 2021). The crystallographic orientations of the magnetite needles likely resulted from the minimization of both interfacial energy and atomic rearrangement. Interestingly, the needle inclusions seem to appear only in more calcic plagioclase feldspars (andesine, labradorite, bytownite, and anorthite), whereas the thin-film and platy iron oxide inclusions (hematite or magnetite) are primarily found in sodic plagioclase and alkali feldspars (oligoclase, albite, and orthoclase) (Jin et al., 2022b), although both types of inclusions have been observed in labradorite from Canada (figure 22D) (Jin et al., 2021). Several factors might contribute to this different morphology of iron oxide inclusions, including lattice parameters and crystal structures, anisotropic diffusion of iron, and thermal and redox histories.

GOLDEN SHEEN SAPPHIRE

Another example of gemstones displaying both asterism and aventurescence is gold sheen sapphire (or Zawadi sapphire) reportedly from Kenya (figure 24, left), yet the exact location of the mine is still unclear (Bui et al., 2015; Soonthorntantikul et al., 2016). Although most star sapphires can display a weak shimmer or sheen on a flat polished (001) surface, gold sheen sapphire shows a much stronger aventurescence, comparable to that of sunstone. A facet-grade aventurescent sapphire, with an appearance resembling Oregon sunstone’s schiller (figure 24, right; Sripoonjan et al., 2019), was also reported with a Kenyan origin, although it may not be from the same mine as the typical translucent to opaque material. And obviously, gold sheen sapphire also displays very strong asterism in a cabochon cut (Bui et al., 2015; Miura et al., 2018). Most inclusions in gold sheen sapphire are the typical acicular hematite and ilmenite as in most star sapphires but noticeably denser in number (again, see figure 8C). Many of these hematite and ilmenite inclusions also expand into flaky shapes, sometimes with irregular edges, which further enhances their reflectivity. Dark platy magnetite inclusions with triangular or rhombic shapes, like those observed in rainbow lattice sunstone, are also found in gold sheen sapphire (Bui et al., 2015; Narudeesombat et al., 2018) and have not been reported in other star sapphires. The occasional goethite inclusions are likely from late-stage alteration of hematite and magnetite, as much gold sheen sapphire material is severely fractured. Unsurprisingly, the iron concentration in gold sheen sapphire is on the higher end for natural sapphire, but there is nothing unusual about the trace element chemistry of these stones (Miura et al., 2018; Narudeesombat et al., 2018; Sripoonjan et al., 2019). The flaky iron oxide inclusions with irregular edges parallel to the (001) plane strongly suggest solid-state precipitation of oversaturated iron from the corundum lattice instead of epitactic crystallization during crystal growth, because most gold sheen sapphire material shows obvious hexagonal {110} growth zoning parallel to the c-axis. These sapphires may have experienced some special thermal and redox histories that promoted the precipitation of iron, and further investigation is warranted. It should be noted that there is most certainly a marketing bias for these heavily included sapphires, because the more common black star sapphires from Thailand, Cambodia, or Australia can also display a strong golden sheen on flat polished surfaces but are never noted for their aventurescence. Nonetheless, since the name gold sheen3 is more closely associated with the Kenyan material, perhaps the more general term golden sheen sapphire could be used for heavily included sapphires of unclear origins that display a strong golden aventurescence.

3At the time of writing, “Gold Sheen” is a refused and abandoned trademark application (#87535320) by the United States Patent and Trademark Office, although it (or its translation) may be a valid trademark in some other markets.

SHEEN AND IRIDESCENT OBSIDIAN

Some obsidian glasses display a diffuse sheen due to reflections from aligned inclusions, which sometimes qualify as aventurescence. Depending on the color of the reflection, they are commonly referred to as silver sheen obsidian or gold sheen obsidian (figure 25, A and B; videos 4 and 5). Some obsidian, often called rainbow or fire obsidian, can display a wide range of iridescence (figure 25, C–F; Johnson and Koivula, 1997). Unfortunately, despite the availability of this material, studies of these included volcanic glasses are extremely limited, providing little information on the mechanism creating the optical phenomenon. Obsidian is an amorphous solid formed by rapid quenching of siliceous melts, an extremely fast process far from equilibrium, and it is therefore more difficult to determine the parageneses of the inclusions in obsidian relative to those for crystalline mineral hosts that are mostly controlled by thermodynamics. Lenticular features filled with gas or glass of a different composition, flattened and aligned due to the flow of the silicic melt, along with oriented pyroxene or feldspar crystals, have been reported in samples of Mexican obsidian, which can contribute to the sheen from internal reflections (Ma et al., 2001). Thin layers measuring 300 to 700 nm thick filled with nano-size magnetite crystals observed in fire obsidian from Glass Buttes, Oregon, may cause thin-film interference and explain the rainbow colors (Ma et al., 2007). A recent study showed that these aligned inclusions in obsidian can not only produce special optical effects but also create complex magnetic properties in these natural glasses (Mameli et al., 2016). Given the dramatically different appearances of sheen obsidians from different locations, multiple mechanisms could be involved in creating these optical phenomena.

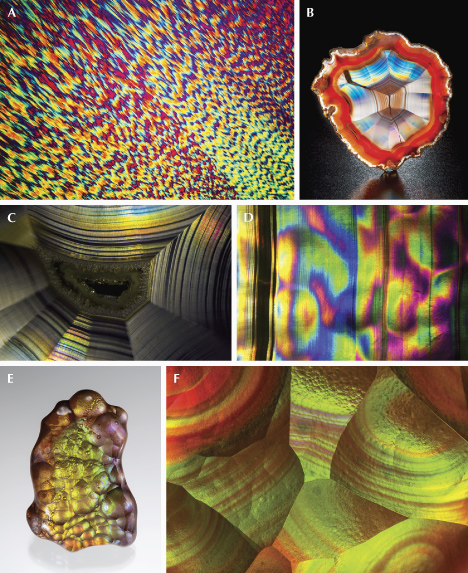

IRIDESCENCE IN FELDSPARS

Iridescent feldspars are the most studied phenomenal gemstones, mainly due to their accessibility and geological importance. Prominent physicists Robert Strutt, fourth Baron Rayleigh (son of third Baron Rayleigh, who discovered Rayleigh scattering) and C.V. Raman (who discovered Raman scattering) both investigated these spectacular phenomenal stones during their careers (Strutt, 1923a; Raman, 1950a; Raman and Jayaraman, 1950, 1953a). The amount of research on this subject could easily constitute a separate review article on its own. Only the results of the studies that are most relevant to the gemological and optical properties of iridescent feldspars will be summarized in this section.

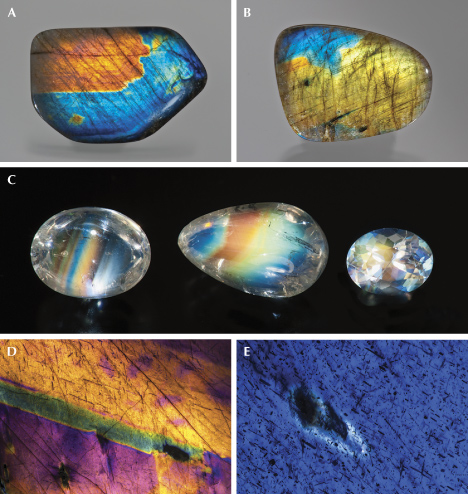

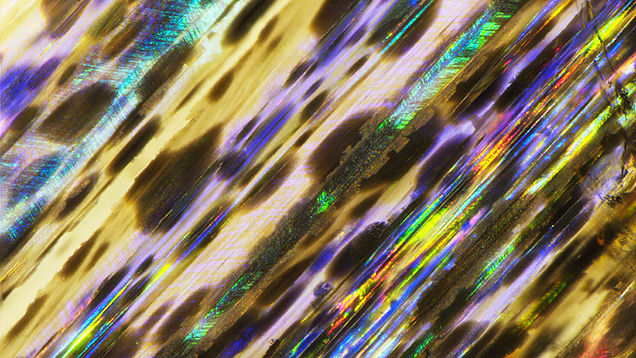

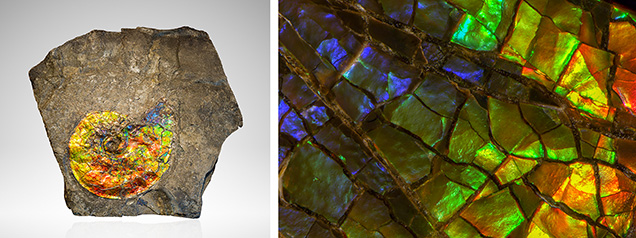

Iridescent feldspars generally can be separated into three categories based on their bulk chemical composition: labradorite, peristerite, and moonstone (figure 26), all of which owe their optical phenomena to submicron intergrowth textures resulting from solid-state exsolution (figure 27). Because oriented iron oxide inclusions are so common in feldspars, iridescent feldspars often also display aventurescence at a different orientation (figure 22). In fact, uniform golden aventurescence in some sunstones can appear quite similar to yellow/orange iridescence in labradorite (figure 23).

To avoid confusion, Smith and Brown (1988, p. 20) tried to redefine the term schiller to be reserved only for reflections from visible inclusions, as in aventurescence. Unfortunately, such an attempt to change the definition of a long-used term is unlikely to be widely adopted, especially since the term has been equally (if not more) commonly used for iridescence than for aventurescence (e.g., Colony, 1935). In this article, “schiller” is defined as any specular reflection arising from within a crystal, either because of flaky inclusions or exsolution lamellae, as long as it is strongly directional.

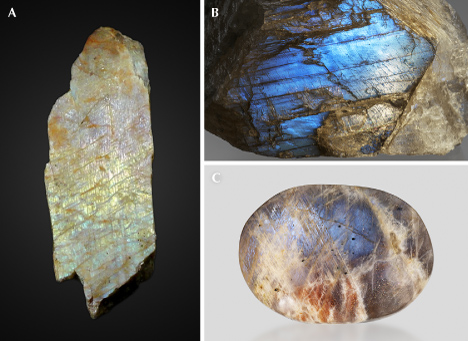

Iridescent Labradorite. The term labradorite, without any modification, refers to any plagioclase feldspar with a composition between An50 (50 mol.% anorthite and 50 mol.% albite) and An70 (70 mol.% anorthite and 30 mol.% albite) (figure 26). For instance, most Oregon sunstones are labradorites. The name labradorite originated from its type locality, Paul’s Island in Labrador, Canada, which produces the most famous iridescent variety. Iridescent labradorites are found around the world in plutonic rocks that experienced extremely slow cooling or high-grade metamorphism, with bulk compositions between An46±2 and An60±2 (Ribbe, 1983; Smith, 1983). These crystals can grow to exceptionally large sizes, sometimes up to several decimeters. Anorthosite rocks composed of iridescent labradorites are often used as high-end countertop materials. The best-quality iridescent labradorites are found in Canada, Finland, and Madagascar.

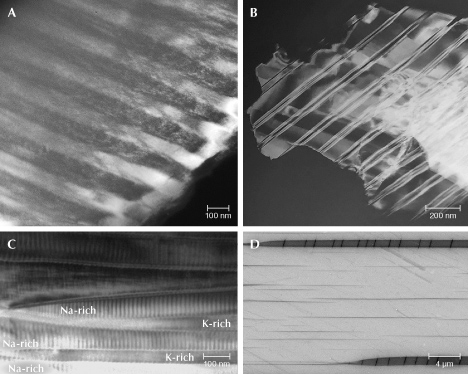

The exsolution texture in iridescent labradorite, known as the Bøggild intergrowth, is composed of alternating wider calcic lamellae (~70–200 nm) and thinner sodic lamellae (~50–100 nm), which are mostly oriented parallel to the (3 20 2) plane (Bøggild, 1924), making the iridescence observable on the (010) cleavage surface. The iridescent color correlates with the average thickness of the lamellae, such that a total thickness of adjacent calcic and sodic lamellae of ~150 nm yields blue iridescent colors, >250 nm yields red iridescent colors, and a continuous prismatic spectrum is observed in between (Ribbe, 1983). The periodicity of the Bøggild intergrowth is very regular (figure 27A) compared to exsolution textures in other minerals, so the iridescence of labradorite is almost always intense with high saturation (figure 28). As a result, the iridescent spectrum can be predicted using a relatively simple kinematic theory of light reflection (Bolton et al., 1966), and the appearance rendered by computer modeling of the iridescence is quite realistic with only a few parameters (Weidlich and Wilkie, 2009).

Although labradorites with the same iridescent color from different locations can have different compositions, the iridescent color zones within the same crystal are always directly correlated with the composition, with the red iridescent zone ~2–3 mol.% more calcic than the blue iridescent zone (Jin et al., 2021). Because of this high sensitivity to small chemical variations, the iridescent color zones in labradorite often feature straight, sharp boundaries (figure 28, A–D), which are not observed in other iridescent feldspars. This characteristic is interpreted to reflect the special shape of the miscibility gap creating the Bøggild intergrowth, which is an inclined loop that closes at low temperature (Jin et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the exact shapes or even topologies of the Bøggild intergrowths are still not fully resolved, mainly due to the challenges of accurately analyzing the composition of individual lamellae, as well as the limited numbers of samples studied in detail (Jin et al., 2021).

The bodycolor of iridescent labradorite is mainly determined by the density of iron oxide inclusions, as most calcic plagioclases from plutonic rocks are clouded. The darkness of labradorite can dramatically affect the appearance of iridescence by controlling the depth of the light reflected by the lamellae inside the crystal. Spectrolite from Finland, with a nearly black bodycolor, shows iridescence at the surface of the crystal (figure 28, A and D), whereas “rainbow moonstone” labradorite with almost no iron oxide inclusions (Koivula, 1987; Win and Moe, 2012) shows diffuse iridescence coming from deeper inside the crystal (figure 28C), resulting in an appearance that may be confused with moonstone, as suggested by its name.