Namak Mandi: A Pioneering Gemstone Market in Pakistan

Introduction

Descending into Peshawar for the first time, a foreign tourist might be surprised to learn that amid the clutter of buildings in this historical city lies an important gem trading center. This market serves a wide range of buyers and sellers from Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Iran who deal with locally mined gemstones from Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan, and parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan (figure 1). They might also be surprised that this trading hub does not have a modern name. Namak Mandi, meaning “salt market” in Urdu, was originally established decades ago as a trading center and storage facility for salt (Hussain, 2015). Fifty years ago, no one could have imagined it becoming a primary trading center for rough and faceted gemstones in Pakistan. The authors led an excursion to Namak Mandi to document its transformation into a gem trading hub and to understand the variety of gemstones and commerce taking place in the market.

FROM SALT TO GEMSTONES: NAMAK MANDI’S TRANSFORMATION

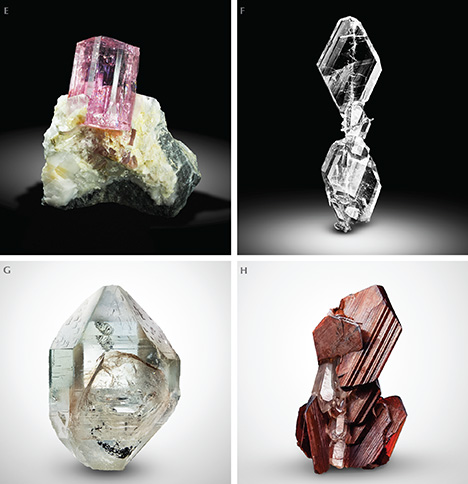

Namak Mandi is the largest market in Pakistan for trading rough gemstones (figures 2 and 3). There is no record of exactly when it made the quantum leap from salt market to becoming Pakistan’s pioneering trading hub for gemstones. According to anecdotal evidence, Namak Mandi’s gemstone market began in the 1970s. Since there were only a handful of traders, the market did not operate systematically and there were no trade standards. With the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the influx of millions of Afghan refugees into Pakistan turned out to be a blessing in disguise. First, the number of traders multiplied as Afghan entrepreneurs penetrated the gem market. Afghan and local dealers from mining areas began to migrate with their stones and established themselves in Peshawar (figure 1). In fact, Afghan traders soon became the driving force for the market, accounting for 60–70% of sales up until 2007. Those from Kunar Province of Afghanistan exported tourmaline (figure 4A) to Namak Mandi, along with spodumene from Nuristan (figure 4B; Rehman et al., 2020) and emerald from the Panjshir region. Within Pakistan, merchants from Swat Valley (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) traded emerald (figure 4C), while those from the Gilgit-Baltistan region brought aquamarine (figure 4D), and pink topaz came from Katlang, a township in the Mardan District (figure 4E).

Many inhabitants of different regions of Pakistan also moved to Peshawar for the gemstone trade. These included Chitral, Skardu, Swat, Karachi, Rawalpindi, and Islamabad. More recently, traders from Baluchistan Province have also entered the market, introducing stones such as Faden quartz with an internal thread-like pattern (figure 4F), quartz with yellowish to deep yellow petroleum inclusions (figure 4G; as described by Laurs, 2016), and brookite (figure 4H). The 1980s saw the Namak Mandi market gain international attention. Still, it was not without a downside: Police and local officials often believed that the people involved in the gemstone business were money launderers. In interviews with experienced tradesmen, it became clear that because there was no legal framework for extracting, processing, and trading of gemstones, the officials likened it to the narcotics trade.

ESTABLISHMENT OF EXPORTERS’ ASSOCIATION

With Afghan merchants leading the expansion of gemstone trading in Namak Mandi, it was not surprising to see them establishing a stronghold, as they possessed knowledge of the market on a local and international level. In a move to somewhat formalize the trade and, perhaps, to check the Afghan monopoly, local traders led a move to register their businesses with the All Pakistan Commercial Exporters Association (APCEA), established in 1984. In 1988, the Ministry of Commerce granted it official recognition to assist exporters registered with the organization. The APCEA caters to the needs and challenges faced by exporters from all industries. Since Namak Mandi’s exporters did not have an official agency that could handle their needs (e.g., quick processing of exports and payment of export duties), they found it expedient to register their businesses with the APCEA. The association plays a positive role for Namak Mandi in many ways. By informing the authorities about the significance of the gemstone trade for the local economy, it saves traders and exporters from police harassment. It also actively supports exporters in processing their documents at customs offices for sale abroad. Owing to the commercial success of Namak Mandi with the support of the APCEA, the gemstone sector has become more prominent, and many local traders are keen to know more about this lucrative trade to capitalize on this market. The APCEA also organizes an international gemstone exhibition each year in the capital city of Islamabad.

Gemstone Business Tree. The gemstone business in Namak Mandi and in Pakistan as a whole can be categorized into three main groups of dealers:

- Rough and Faceted Stones: This category is comprised of those who have some lapidary skills. It is worth mentioning that there is no professional organization in Pakistan delivering lapidary training. Since most of the local lapidaries are not formally educated, each would develop specialist knowledge about a specific type of gemstone. In Namak Mandi, it is common to find dealers who specialize in emerald, kunzite, aquamarine, or tourmaline. These dealers invest their money in a specific gemstone and are considered experts in determining the base price of that particular type of gemstone.

- Mineral Specimens: Specimen dealers can be grouped into two categories: the local traders who showcase mineral specimens in shops at Namak Mandi, and those who understand online selling and export mineral specimens to Canada, Australia, the United States, and other developed countries. The latter comprise almost 80% of specimen dealers. They often take pictures and videos of local traders’ collections of mineral specimens for online marketing. If a customer demands a specific item, an online trader, after negotiating the price with the local (shopkeeper) trader, adds his profit to the price and parcels it off. Most exporters do this type of business because there is almost zero risk of losing one’s money. That is, they can make money without having to buy and keep the specimens in rented shops; like the middlemen, they make money without incurring financial risk.

- Ornamental Stones: Namak Mandi’s ornamental stone dealers mostly deal in lapis lazuli and nephrite. World-famous lapis lazuli comes from Afghanistan (figure 1). The exquisite color of lapis from Kokcha in Badakhshan Province is especially popular (figure 5). There are many mines in Badakhshan, some of which are simply named mine 1, 2, 3, and so forth. Mine 4 is particularly esteemed among the traders. The mine is referred to as Ma’dan-e-char, Persian for “mine 4.” Lapis lazuli from this mine has an exceptionally vivid blue color, with very little or no pyrite and calcite. At Namak Mandi, the mere mention of a lapis coming from Ma’dan-e-char is considered a guarantee of quality. As this gemstone hails from Afghanistan, most lapis traders tend to be of Afghan origin.

Within Pakistan, nephrite mostly comes from the Mohmand region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (figure 1). The area produces some of the world’s most brightly colored emerald green nephrite (figures 6 and 7). According to interviewees, nephrite from the Hamid mine and the Siraj mine in the Mohmand region are in especially high demand in China. Chinese consumers desire its emerald green color and absence of black oxide spots. While some of the nephrite from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is used in jewelry and for different types of carvings and beads for sale in the local market, most of it is exported to China, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Merchandising Tactics and Negative Effects. There is a saying in Namak Mandi: “Demand a lot from God and your customer.” This quote is seen as the way to become profitable in business endeavors. Another saying goes, “If you learn the tricks of trading in Namak Mandi, you can deal in any market in the world.” Keeping this in mind, below we highlight a few pricing and trading tactics.

Colored gemstones have no internationally recognized pricing mechanism. Seemingly aware of this, Namak Mandi traders tend to take advantage, inflating their stone prices using various tactics, such as declaring a higher cost price than what they actually paid. First, when a dealer (Mr. A) indicates the slightest interest in a gemstone, Mr. B might witness this display of interest and take a gamble and buy a speculative stake with Mr. A without exchanging money. That is, if Mr. A buys a gemstone for US$1,000, Mr. B will swear that its value is at least US$1,500 and that if he could afford it, he would have bought it for at least that price. Similarly, if Mr. A has more business “friends,” each of them will make similar claims to drive the price even higher. In this way, a gemstone purchased for just US$1,000 will have its price raised many times. Thus, when Mr. A is about to sell it, he will swear to a customer—often in the presence of his business associates—that he bought it for US$3,000, and thus he will set its price at around US$4,000. This ritual of increasing the price of a gemstone by solemn oaths and buying a speculative stake without exchanging a good has developed out of religious reasons. That is, for religious reasons, a Namak Mandi trader would take solemn declarations from his business peers to set a new cost price of his item while avoiding any allegation of dishonesty when telling people of the new cost price.

Second, some families engaged in mining resort to another tactic. The mine owner inflates the cost price by giving each family member a share in every piece of extracted gemstone. The price cost of a stone, normally determined by adding the costs of labor, machinery, transportation, and so forth, is determined in this case by showing it to experienced tradespeople and the like. If the experts set a “cost price” of US$1,000 and a mine owner has four family members, then he will count a share of US$500 for each of the four family members. It is important to highlight that this only occurs verbally, without ever giving the shares to the family members. This will increase the stone’s cost price by US$2,000 (US$500 each × 4), resulting in a new price of US$3,000.

Third, gemstones coming for auction from Afghanistan are dealt with in a different way. Bidders tend to engage in blind bidding for the stones. Hundreds of bidders will buy a share in a specific lot without ever seeing a single gemstone. According to the conventions of the Islamic faith, one cannot buy something that exists only in the abstract. Nonetheless, the practice of buying shares in an unseen lot of gemstones at auction has become a mainstream practice at Namak Mandi.

Finally, traders tend to be inconspicuous about their inventory, not displaying gemstones and closing the curtains once customers enter their stores. They use these tactics so that other traders do not see the stones they are showcasing to their customers; it also allows them to avoid price competition with their competitors.

Customers and traders alike frequently become disheartened, believing they have been cheated or have paid far above market price. Some eventually leave the gemstone industry altogether. These questionable business practices seem to reflect a persistent notion that government bureaucracies in Pakistan do not function to serve the masses. Citizens often have to request access to information, such as import/export policies, that is constitutionally guaranteed as a “fundamental right.” For instance, the drive to register one’s business with the APCEA was a purely voluntary effort among gemstone traders. That is, a state agency or department did not direct or advise them how to effectively and smoothly import and export gemstones: It was the business acumen of a few entrepreneurs that led to the custom of registering one’s firm with the APCEA. Likewise, some traders are now taking the initiative in addressing ethical issues in pricing and trading tactics, albeit slowly. Most importantly, according to some interviewees, customers’ ability to quickly share their concerns regarding trading practices at Namak Mandi on social media platforms, especially Facebook, is incentivizing dealers to become more responsible and ethical.

Regardless of the ethical norms regarding price setting, Pakistan’s largest auctions take place in Namak Mandi, and the highest bids are often placed by local merchants. Namak Mandi’s merchants frequent trade shows and other exhibitions such as those held in China, the Tucson show in the United States, and Bangkok. They import many stones into Pakistan and export them to other countries.

Gemstone Supply Chain at Namak Mandi. As illustrated in figure 8, there are two ways for a gemstone to go from the mine to the end user through the Namak Mandi gem market. The first route is through the main contractor—the individual who leased the mine. After mining, the gems are sorted according to quality. Whenever stones are bought from him directly, he will narrate a long story recounting how much money was spent on leasing and mining. Known as the toughest negotiator, the main contractor always demands a very high price for his product. Such sellers mostly deal in rough gems: The high-quality samples often go to the international market, while the medium- to low-quality material is sold locally at Namak Mandi or elsewhere in Pakistan.

A second route through which a gemstone travels from mine to market is through the subcontractor. He has two sources for collecting gemstones: the mine owner and the miners themselves. Usually, miners have a labor production sharing agreement with the subcontractor. As depicted in the flowchart (figure 8), miners sell off their share to subcontractors. The subcontractor selling the mined product (rough and faceted) in Namak Mandi and elsewhere is more like a middleman or a commission agent. Because miners do not have the know-how and requisite financial resources for dealing with traders at Namak Mandi and other markets, they have to rely entirely on selling the items to subcontractors. According to our information, miners are at liberty to sell their product at local auctions but prefer subcontractors, who offer fairer deals.

PERSISTENT AND EMERGING TRENDS

A first-time visitor to Namak Mandi who has some knowledge of gemstone trading hubs such as China, Thailand, and Sri Lanka would immediately notice that it has probably some of the lowest-quality cutting. Namak Mandi’s cutters still use a tool called the angoora, shown in figure 9C. The angoora is a metallic handle, one side of which is bent in such a way that it works as a base for angular positioning of the tool. On its opposite side (toward the thumb side in figure 9C), it has an adjustable hole with a copper screw to hold the wooden dop-stick, called a khandee (figure 10) in Pashtu. The tool does not have any angle settings. It is also important to highlight that the entire process using the angoora and khandee is done by hand, using the unaided eye.

Before cutting and polishing with the angoora, a lapidary first pre-forms a gemstone, either by hand or using a khandee. This is done to shape the stone so that it can be easily and firmly mounted on the top of the khandee (figures 9A and 9B). To dop the stone, the lapidary uses a combination of superglue and hot wax that is wrapped around the top of the khandee to firmly fix a gemstone onto it for faceting. The combination of glue and wax is referred to locally as ma’waa. The stone is manually positioned in the hot wax, a skill that takes years to develop. The next task is to place the crown angles, which is also done entirely by hand. Next, the lapidary inserts the khandee into the angoora. Since the angoora does not have angle settings, it is entirely up to the ability and experience of the lapidary to meticulously shape the stone, checking and rotating it every few seconds to place facets evenly according to the design desired by the customer.

Once the faceting is complete, the lapidary takes the stone out of the angoora to facet the table. Next, a copper lap is used to polish the stone. Here again, the entire process is done by hand. For instance, while observing a local lapidary, Mr. Sajid, we noticed that he regularly used kerosene to wipe the surface of the copper lap clean. He would also apply diamond powder to achieve the required polish. Once the process was done, the gemstone was removed from the khandee and flipped upside down to follow the same procedure to facet and polish the pavilion. It took Mr. Sajid about an hour to complete the entire faceting and polishing process (figure 11). Mr. Sajid also informed us that some stones could take longer if the desired shape had a more complex pattern with many more facets than standard cuts. While the process is time-consuming, most traders doing business outside Pakistan recut the stones in Thailand, Sri Lanka, or China to increase their value in the international market.

Nonetheless, the angoora’s use is justified on two grounds. First, it saves stone weight, allowing for a higher price per carat. According to the local lapidaries using the angoora, modern faceting results in loss of weight. Our understanding is that because they lack formal training and education, Namak Mandi’s lapidaries do not have the proper know-how of a modern faceter. Hence, they justify clinging to the angoora by saying that it retains weight. Second, in the words of Mr. Sajid, an angoora expert: “Just as we prefer an Afghani handmade carpet over a machine-made piece, so do people [in/around Namak Mandi] prefer a stone faceted with angoora.” This remark, which was echoed by other lapidaries and retailers, can be interpreted in two ways. First, it is worth mentioning that mastering a modern faceting machine might cognitively require a higher level of formal education than using an angoora, but to become an expert in using the angoora, one must invest years of apprenticeship under an ustad (mentor). Modern faceting is counterintuitive to the decades-old tradition of ustad-shagird (mentor-mentee). It could also be argued that because experienced angoora users took years to master the art, they have a vested interest in continuing the tradition rather than accepting a change that, besides requiring an investment of time and financial resources, would ultimately wipe out their hard-earned skills.

In addition to the angoora culture, we documented Namak Mandi’s online gemstone market. Somewhere around 2010, a handful of traders in Peshawar started doing business on eBay. At the time, this was a niche marketing strategy for exporting gemstones from Pakistan to the rest of the world, but it enabled them to gain repeat and long-term customers. Many merchants, particularly those originating from Afghanistan, would introduce the younger generations to the gemstone industry. The younger traders began to find innovative ways of selling their products. But Namak Mandi faces two obstacles in achieving the full potential of online sales. First, eBay accounts are usually linked to the most popular payment system, PayPal, which does not operate in Pakistan. Sellers tend to migrate abroad and set up their accounts from countries such as Thailand. Second, rogue traders tend to generate negative perceptions of the Pakistani gemstone market. They create Facebook accounts, attracting buyers with flowery language, and then sell them gemstones for above-market price or defraud their customers by providing the wrong stones altogether. The sellers also use camera effects to completely misrepresent the true features of the stone. In most cases, eBay closes such accounts. Although the fraud rate has fallen dramatically as eBay introduces new measures to combat these transactions, such practices have hindered Namak Mandi’s online gemstone market. Thus, scandals and stories regarding online fraud are gradually making inroads for more ethical and responsible trading.

Finally, Pakistani women are starting to buy and sell gemstones online, which could be a game changer. Pakistan’s gem trade in general and Namak Mandi, in particular, is a male-dominated marketplace. Women tend to avoid trading in such a “hostile” market. To navigate around this challenge, women entrepreneurs are doing business on eBay. Many are brokers: They arrange deals between traders in Pakistan and buyers who are based locally or globally. Since the few women who have entered the online marketplace are reportedly doing business quite ethically, they could ultimately influence their male counterparts to operate just as ethically, lest they lose their share of the market.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the last 50 years, Namak Mandi has evolved from a salt storage and trading market into a thriving gemstone business hub pulling local and Afghan traders. The exchange of rough and faceted stones, mineral specimens, and ornamental stones has turned it into a pioneer gemstone market in Pakistan. This transformation has come about with the sole support of APCEA and, literally, zero support from the relevant government departments. Nonetheless, the local and online business at Namak Mandi has been marred by complaints about unethical business practices. These primarily include: (1) occasionally duping the customers with low-quality gemstones and (2) charging exorbitant prices for the merchandise. Similarly, the lack and non-acceptance of modern faceting facilities potentially hinder Namak Mandi’s traders from firmly finding a niche in or competing with regional gemstones centers in Thailand, China, India, or Sri Lanka. By and large, women traders’ recent entry into the market, who reportedly do business ethically and responsibly, could pave the way for improving business culture overall.