Green Opal Displaying Aventurescence

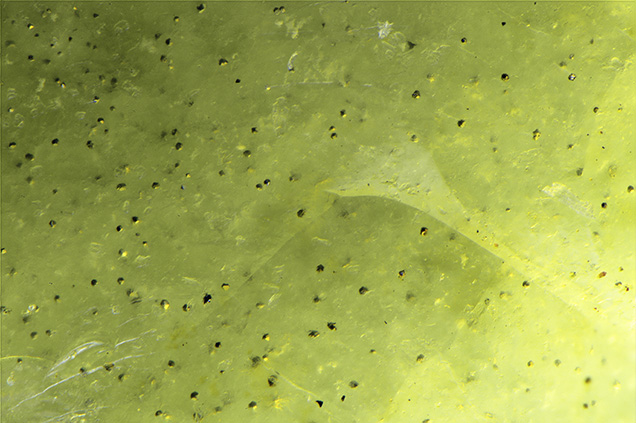

Recently the Carlsbad laboratory received a variegated dark green and blue partially polished rough stone for identification services. The stone measured 23.64 × 20.13 × 15.52 mm and weighed 23.74 ct (figure 1). A vitreous to waxy luster and bright yellow inclusions were observed.

Standard gemological testing revealed a refractive index spot reading of 1.43 and a specific gravity of 2.15 obtained hydrostatically. These properties were consistent with opal. During microscopic analysis, fine hazy clouds and turbidity were seen within the structure, as well as a reddish brown portion with iron staining. Although no play-of-color was observed, an unusual aventurescence was seen in several areas with fiber-optic lighting while rotating the stone. This unusual phenomenon was caused by the scattering of light from the small, eye-visible yellow inclusions (figure 2). These inclusions were later confirmed by Raman spectroscopy as pyrite.

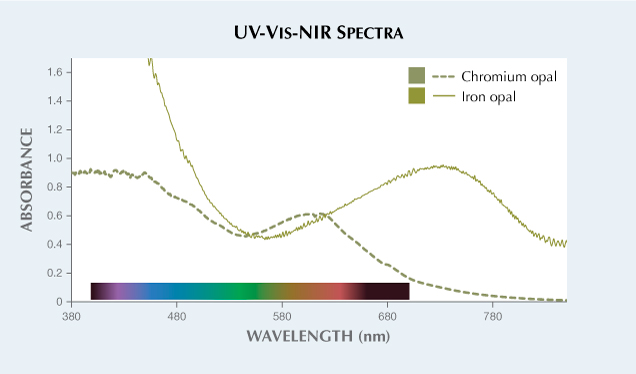

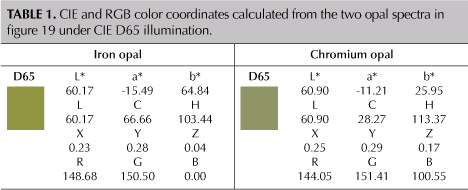

LA-ICP-MS analysis was performed on the sample to investigate which chromophore was responsible for its green color. The results showed that the stone contained approximately 3540 ppma Fe. No other chromophoric trace elements were measured in significant quantities, indicating that iron was most likely the cause of the green color. UV-Vis-NIR spectra were collected and used to quantitatively calculate the color of this material (figures 3 and 4, table 1). In figure 3, a broad absorption band centered at about 741 nm produces the green color of the opal. This absorption band is likely related to octahedral Fe2+. Previous publications have shown that iron can produce green color in quartz due to an absorption band centered at 741 nm relating to interstitial Fe2+ (L.B. Hebert and G.R. Rossman, “Greenish quartz from the Thunder Bay amethyst mine panorama (TBAMP), Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada,” Canadian Mineralogist, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2008, pp. 111–124). Octahedral Fe2+ can strongly absorb red, orange, and some portion of yellow light of the visible spectrum to produce a transmission window in the yellowish green region. In this case, a transmission window around 570 nm results in the green color in the iron opal (solid line in figure 3). The presence of some additional Fe3+ cannot be ruled out and may contribute to the rise in absorption at shorter wavelengths into the UV region.

Another type of green opal colored by Cr3+ (Winter 2020 Lab Notes, pp. 520–521) was compared with the iron-colored opal (solid line in figure 3). Cr3+ produces a smaller absorption band centered at about 600 nm, leading to a transmission window in the green region around 540 nm that causes a less yellow and more pure green color (figure 3).

The two color panels calculated from the two spectra were also plotted in the CIE L*a*b* 1976 color circle seen in figure 4. This allows for a more accurate comparison between the two color panels using quantitative colorimetric data. In the plot, the hue angle of the iron opal is smaller than chromium opal, resulting in a more yellowish green hue. The chroma of the iron opal is larger than that of a chromium opal with similar lightness, resulting in a more saturated color.

This green common opal is a clear example of iron contributing to the yellowish green color, in contrast to the more pure green color due to the chromium in the opal previously documented with a slightly grayish green color. Both the yellowish green color and pyrite inclusions are consistent with an iron-rich environment. The pyrite inclusions also add a unique display of aventurescence not typically seen in common opal.