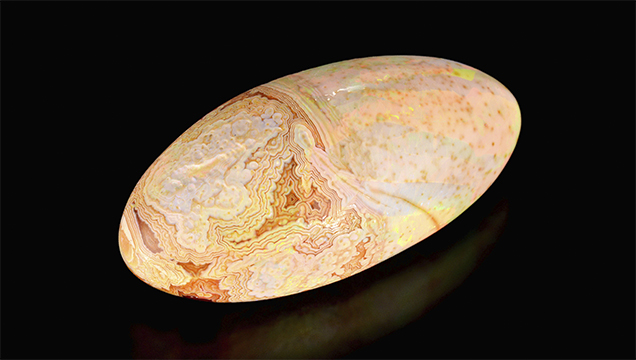

Opal with Agate-Like Banding

Recently, author SC purchased an interesting Ethiopian opal (figure 1) that displayed a most unusual growth structure. A portion of the orangy brown opal displayed a small patch of wavy “varve” banding much like one would expect to see in an agate (figure 2). The banded area was composed of layers of translucent dark brown material alternating with lighter opaque material. It was also evident that the dark layers were much harder than the lighter layers, which had significant undercutting on the polished surface. These lighter areas also showed play-of-color, which made it obvious that they were precious opal layers. The dark areas did not show play-of–color, leaving it unknown if they were also opal or perhaps chalcedony, consistent with their banded pattern. It was also interesting to note that the lighter areas readily absorbed water and became transparent, an indication of hydrophane opal.

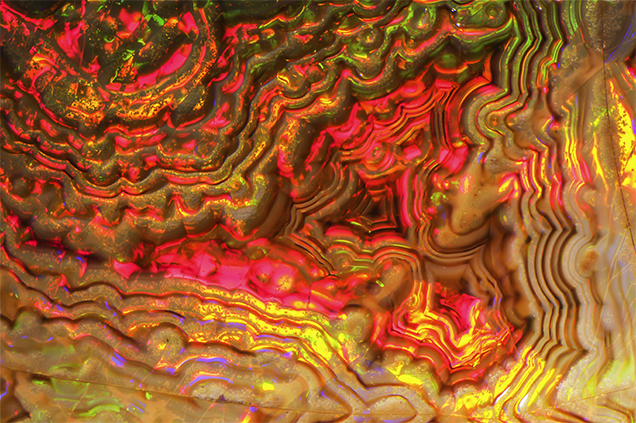

Careful microscopic observation yielded some interesting conclusions. A few small healed cracks in this stone were naturally repaired with opal infilling. Some of these cracks showed a lateral offset as they cut across the banding (figure 3, left). We also observed that the fractures that showed an offset in the banding showed no offset in the “photonic crystal” (B. Rondeau et al., “On the origin of digit patterns in gem opal” Fall 2013 G&G, pp. 138–146), or in the single play-of-color patches (figure 3, right). These observations are important in revealing the order of events that took place to produce such a specimen. First, the deposition of chalcedony had to occur in order to produce the crenulated (wavy) banded pattern. Second, stress cracks were introduced into the agate and then laterally shifted, creating several “micro-faults.” These micro-faults were subsequently “healed” with a secondary deposit of opal. This secondary opal deposition also replaced the chalcedony while preserving the original agate-like banding, which was apparent since there was no offset along the micro-faults in the patches of play-of-color.

This is one of the most unusual opals the authors have encountered to date. The microscopic observations tell an interesting story about the formation of a unique gem.

.jpg)