Ametrine Optical Dishes: Windows into the Effects of Crystal Structure

During exploration of a gem’s interior, it is important to understand how crystal structure affects the incorporation and orientation of inclusions, how an inclusion can affect its host, how interpretation of observations can depend on point of view, and the nature of light as it passes through a crystal—host or inclusion. As proposed earlier in this column (Spring 2016, p. 81), polished inclusion study blocks are ideal for showcasing, studying, and reviewing basic concepts relating to the micro-world. Here we take a look at light and crystal structure.

Of all the varieties of quartz, ametrine is perhaps the most fascinating to observe. While its stunning color zoning makes it a popular designer gemstone, it also encompasses several optical properties unique to different quartz varieties that can all be explored in one specimen. Almost unrecognizable as quartz, ametrine crystals are deeply etched (figure 1, left) and have abundant healed fractures. The only clues to the trigonal symmetry typical of quartz are occasional rhombohedral faces and, very rarely, an enigmatic flat termination manifesting a three-armed figure (figure 1, right). Only when a basal section is made by cutting a slice perpendicular to the c-axis is the improbable yet beautiful combination of citrine and amethyst revealed.

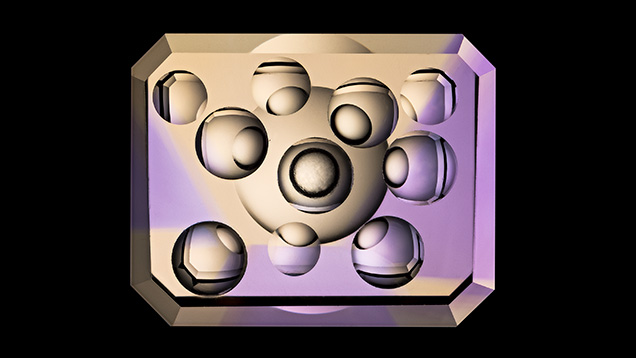

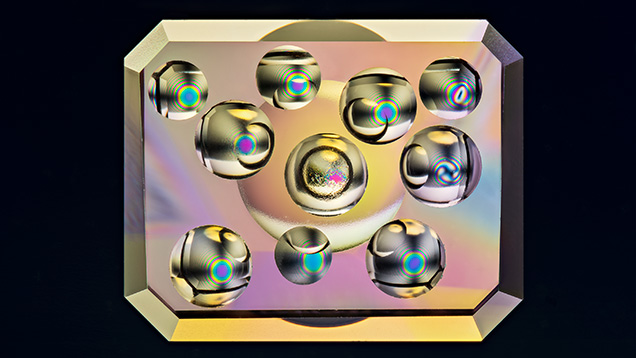

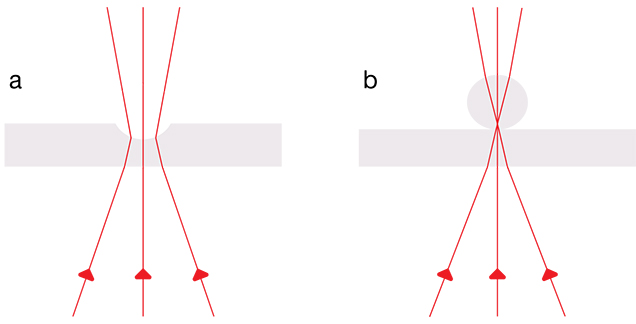

Beauty and function are married in an ametrine study block oriented so that the view through its two largest faces is directly along the optic axis of a crystal, as seen in figure 1. The innovation of adding a set of concave dishes for sampling each color zone, as well as the borders between them, reveals truly remarkable optical phenomena (figures 2 and 3). These optical dishes allow the viewer to see light passing through the specimen in many directions, as does the strain-free glass sphere familiar to gemologists for use with a polariscope (figure 4). When viewed between crossed polarizing filters, these dishes dramatically display the different uniaxial optic figures unique to quartz, which vary depending on thickness and placement in the sectors: the classic “bull’s-eye” optic figure seen in the untwinned citrine sectors, an Airy’s spiral in the amethyst sectors, and a distorted figure produced in a border region. All of these observed phenomena are produced by optical activity (i.e., the rotatory dispersion of light as it travels along the optic axis direction within the quartz crystal). By analyzing these figures, we can determine handedness and the effects of thickness, while observations of the amethyst’s Brazil-law twinning may help distinguish natural versus synthetic origin.

For an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of optical activity and the origin of quartz’s optic figure, see E.A. Skalwold and W.A. Bassett, Quartz: A Bull’s Eye on Optical Activity, Mineralogical Society of America, 2016, www.minsocam.org/msa/OpenAccess_publications

/Skalwold/Quartz_Bullseye_on_Optical_Activity.pdf.