Starburst Cloud Inclusions in Diamond

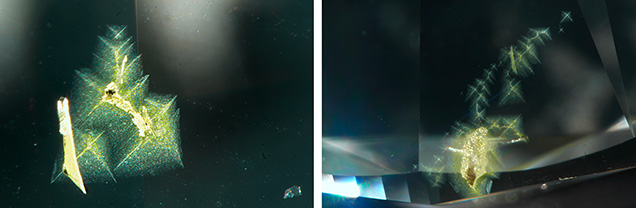

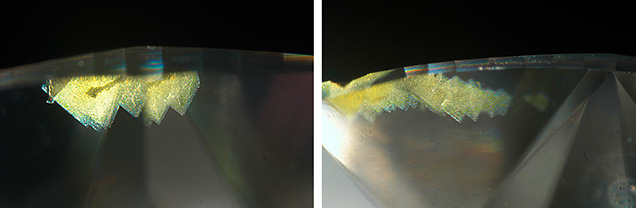

Recently, the Carlsbad laboratory examined a 2.50 ct Faint yellow-green round brilliant diamond with several randomly distributed yellow zones consisting of stacks of clouds with four-sided star patterns near the girdle (figure 1). The clouds were clusters of micro-inclusions, with the center of each cloud containing more intensely colored particles in a cross pattern. When viewed from a different direction, the same clouds appeared as a row of bright yellow overlapping triangles (figure 2). The uniqueness of these clouds triggered an in-depth investigation.

The body of the diamond exhibited blue fluorescence to long-wave (365 nm) UV radiation, and with a deep-UV (<230 nm) imaging microscope, the authors were able to discern that the cloud patches showed weak yellow fluorescence (figure 3).

The diamond’s ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared absorption spectrum revealed cape absorption features at 415 (N3 center) and 478 (N2 center) nm. In addition, broad absorption bands centered at 730 and 836 nm, as well as a peak at 563 nm, were indicative of hydrogen-related defects (C.M. Breeding et al., “Naturally colored yellow and orange gem diamonds: The nitrogen factor,” Summer 2020 G&G, pp. 194–219). The infrared absorption spectrum indicated that the diamond was type Ia with high abundance of both nitrogen and hydrogen.

While hydrogen-related defects might cause brownish or greenish components to the diamond bodycolor, they are not responsible for the bright yellow color zones in this diamond. Generally, yellow color in diamond is caused by cape defects, H3 defects, isolated nitrogen (C-center), or a 480 nm absorption band (Breeding et al., 2020). However, patchy yellow color zones are more often associated with C-centers or a 480 nm absorption band (e.g., Breeding et al., 2020; M.Y. Lai et al., “Spectroscopic characterization of rare natural pink diamonds with yellow color zones,” Diamond and Related Materials, Vol. 148, 2024, article no. 111428).

Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were collected on the bright yellow color zones and the surrounding areas, and neither the H3 center (at 503.2 nm) nor the characteristic PL features associated with the 480 nm absorption band (Lai et al., 2024) were detected. This finding suggests that these were not the causes for the yellow color zones in this diamond. The NV– center at 637 nm, a common feature of diamonds colored by isolated nitrogen, was detected only within the bright yellow color zones, indicating that the yellow color was likely due to the presence of C-centers located in a confined region on the surface of the diamond.

Previously, a yellow overgrowth layer that formed on top of a near-colorless diamond in the late stage of diamond growth was reported (e.g., M.Y. Lai et al., “Yellow diamonds with colourless cores – Evidence for episodic diamond growth beneath Chidliak and the Ekati Mine, Canada,” Mineralogy and Petrology, Vol. 114, 2020, pp. 91–103). However, the composition and formation of the clouds of micro-inclusions coincident with the yellow color zones in this diamond are currently unclear and require further investigation. This diamond with starburst-patterned clouds and patchy yellow zones highlights the crucial role of in situ analytical techniques in gemstone identification, where the causes of color zones can be determined based on well-resolved spectroscopic features.