A Guide to Diamonds with the 480 nm Absorption Band

ABSTRACT

In the gemological research community, diamonds with a broad absorption band centered at roughly 480 nm in the visible spectrum are referred to as “480 nm band diamonds.” Despite the 480 nm absorption band being one of the few causes of yellow bodycolor, diamonds with this feature are relatively scarce and not as widely recognized as those colored by the N3 defect, single substitutional nitrogen defect, or H3 defect. Yet 480 nm band diamonds deserve more attention because they account for the vast majority of rare diamonds with unmodified orange hues, as well as all chameleon diamonds—diamonds with a reversible color-change property. However, the global abundance and distribution of 480 nm band diamonds are currently unknown. To date, only mines in Russia and Canada are known to produce these diamonds, but other sources likely exist. Understanding their gemological and spectroscopic characteristics will help the mining industry and the gem trade identify these obscure treasures. This article summarizes the features of 480 nm band diamonds for rapid identification or advanced gemological testing.

Though natural diamond is composed of carbon, atomic impurities and vacancies commonly occur in the diamond crystal structure, attributed to the incorporation of extrinsic elements and strain induced during diamond growth. Post-growth irradiation and plastic deformation can also produce vacancies in the diamond structure (Van Enckevort and Visser, 1990; Fisher, 2009). Consequently, the otherwise perfectly ordered arrangement of carbon atoms in the diamond crystal structure is disturbed. Some structural defects absorb light in the visible spectrum—the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that the human eye can perceive—producing different bodycolors in diamonds. The defects responsible for color in many diamonds have been well documented, with the majority associated with nitrogen (e.g., Collins, 2001; De Weerdt and Van Royen, 2001; Kanda, 2007; Shigley and Breeding, 2013).

Yellow is one of the most common bodycolors of diamond. The majority of yellow diamonds—known as “cape” diamonds in the gem trade—are colored by the N3 defect (with a structure of three nitrogen atoms surrounding a vacancy) and associated absorptions including the N2 defect (a vibronic transition of N3V) (Breeding et al., 2020). Yellow color in a significant number of diamonds can also come from single substitutional nitrogen (C-center) or from the H3 defect (a vacancy between two nitrogen atoms). A subset of yellow diamonds also contain nitrogen yet are primarily colored by a broad absorption band centered at about 480 nm in the visible spectrum. The 480 nm absorption band has been tentatively attributed to substitutional oxygen (Gali et al., 2001; Hainschwang et al., 2020), and diamonds with this absorption feature are termed “480 nm band diamonds” in the gemological research community. This absorption band has only been observed in natural diamonds, and the defect(s) associated with it have not been produced in natural or synthetic diamonds by commercial treatments (Collins, 2001).

Among all yellow diamonds submitted to GIA in the last decade, <5% have been 480 nm band diamonds. These diamonds have not received much attention in the gem trade because of their relative scarcity. However, it is notable that the 480 nm absorption band is not restricted to diamonds with primarily yellow color but also occurs in a variety of colored diamonds, including some of the most valuable orange and chameleon diamonds. Chameleon diamonds are those with a reversible color-change property, typically turning from a green to a more intense yellow or orange color when they are heated mildly or kept in the dark for a significant period of time (Fryer et al., 1981, 1982; Hainschwang et al., 2005; Fritsch et al., 2007a; Fritsch and Delaunay, 2018). Exposure to ambient light or cool temperatures restores the original color. While the documentation of chameleon diamonds is sparse, it is possible that many of these diamonds have not been evaluated and recognized due to a lack of awareness of their properties. This article provides detailed descriptions of the gemological and spectroscopic properties of the diverse and dynamic 480 nm band diamonds to facilitate their identification in the gem and mining industries.

COLOR VARIETIES AND CORRESPONDING VISIBLE ABSORPTION SPECTRA

The broad absorption band with a maximum at approximately 480 nm extends from violet to green in the visible spectrum, producing a yellow to orange color in diamond. Depending on the range and intensity of this absorption band, 480 nm band diamonds can have a variety of tones and saturations (figure 1). Generally, diamonds with Fancy Vivid, Fancy Intense, or Fancy Deep orange, orangy yellow, or yellowish orange color grades have the strongest 480 nm absorption band (figure 2, A and B). In contrast, chameleon diamonds usually have a much weaker 480 nm absorption band (figure 2C) (Lai et al., 2024a). The cause of green color in chameleon diamonds differs from that in green or blue-green diamonds colored by the GR1 defects (neutral vacancies). GR1 defects can be produced by natural or artificial radiation, and produce a green bodycolor in diamonds that have a yellow hue (Breeding et al., 2018). The green color in chameleon diamonds has been attributed to a transmission window between 500 and 600 nm produced by a combination of the 480 nm absorption band and the additional broad absorption band extending from approximately 600 nm to the near-infrared region (Hainschwang et al., 2005; Fritsch et al., 2007a). The majority of chameleon diamonds also have an absorption peak at 415 nm corresponding to the N3 defect (figure 2C), whereas this absorption feature is far less common in non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds.

The occurrence of additional structural defects can modify 480 nm band diamonds’ colors. For example, single substitutional nitrogen frequently occurs in these diamonds, which could add an orangy or brownish tint to their primary colors. In addition, vacancy clusters in the diamond structure are also a common cause of brown coloration in diamonds (Fisher et al., 2009). In some 480 nm band diamonds with dominant brown bodycolor there is a continuous absorption that increases from the red end of the visible spectrum and reaches a maximum near 500 nm (figure 2D). This increasing absorption may mask the 480 nm absorption band, increasing the difficulty of identifying 480 nm band diamonds based solely on their visible absorption spectra. In this case, other gemological and spectroscopic features are required to detect the existence of the 480 nm absorption band.

On very rare occasions, some non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds contain absorption features typically observed in cape diamonds (figure 2E), with absorption peaks at 415 and 478 nm corresponding to the N3 and N2 absorptions, respectively (Altobelli and Johnson, 2014). Unlike chameleon diamonds (which frequently show N3 absorption in addition to the 480 nm absorption band), non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds with N3 and N2 absorptions generally have yellow or orangy yellow bodycolors without a green component, and N2 absorption has not been observed in chameleon diamonds. Another group of uncommon 480 nm band diamonds contains an additional broad absorption band centered at about 550 nm and a minor absorption peak at 525 nm (Lall et al., 2024). This broad absorption band is the cause of the pink color associated with plastic deformation in most pink diamonds (Collins, 1982, 2001). Diamonds of this variety with a relatively stronger 480 nm absorption band generally have an orange color (figure 2F), whereas those with a more intense 550 nm band tend to have a pink color.

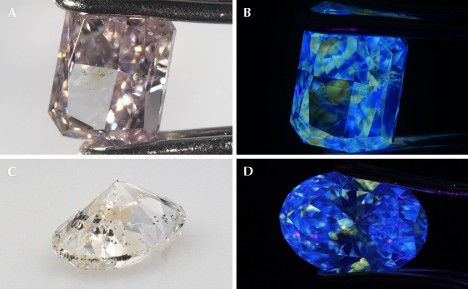

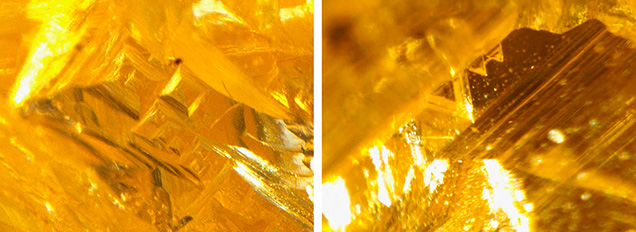

Irregular color zoning is often observed in 480 nm band diamonds when they are viewed microscopically—some zones have a more saturated color, while other zones have lower color saturation and/or are near-colorless. In some extreme cases, the color zoning can be distinct enough that a 480 nm band diamond will appear bicolored or even tricolored (figure 3). A notable example is a chameleon diamond with one half graded Fancy Dark orangy brown and the other half graded Fancy Dark brown greenish yellow; a color-change reaction was observed only in the brown–greenish yellow portion when the diamond was heated (figure 3, right; Lai and Eaton-Magaña, 2023).

RAPID IDENTIFICATION BASED ON GEMOLOGICAL FEATURES

Fluorescence. A quick preliminary screening of diamonds can be achieved using a handheld long-wave ultraviolet (UV) flashlight with an excitation wavelength of 365 nm. Most 480 nm band diamonds have moderate to strong yellow fluorescence, generally corresponding to an asymmetric broad band with maximum intensity at about 540 nm in the fluorescence spectrum excited by the long-wave UV source (figure 4A). It is also fairly common for 480 nm band diamonds to have heterogeneous distributions of yellow and blue fluorescence, where the blue fluorescence is detected in the fluorescence spectrum as a broad band between 400 and 500 nm with overlaying peaks at 415, 429, 439, and 451 nm, all of which are associated with the N3 defect (figure 4B). Moderate to strong orange fluorescence is occasionally observed in 480 nm band diamonds, which is detected in the fluorescence spectrum as a broad band extending from approximately 450 nm to the near-infrared region, centered at about 585 nm (figure 4C).

Excitation wavelengths can affect the observed color and intensity of fluorescence in diamonds. For example, if the UV light source produces light with multiple wavelengths instead of a single wavelength at 365 nm, or if the excitation wavelength is significantly shifted from 365 nm (Luo and Breeding, 2013), the fluorescence will be impacted, potentially enough to be visually observed. This is because fluorescence associated with certain structural defects could be more effectively excited by light with wavelengths outside the intended excitation wavelength. Short-wave UV with an excitation wavelength of 254 nm is also typically used for testing 480 nm band diamonds with a green component, and in order for these diamonds to receive a “chameleon” classification on GIA grading reports, they must exhibit phosphorescence after exposure to short-wave UV (Breeding et al., 2018). All 480 nm band diamonds with a green component and phosphorescence can be tested for color change through mild heating (figure 5). However, phosphorescence is not limited to chameleon diamonds, as it has also been observed in 480 nm band diamonds without a green component.

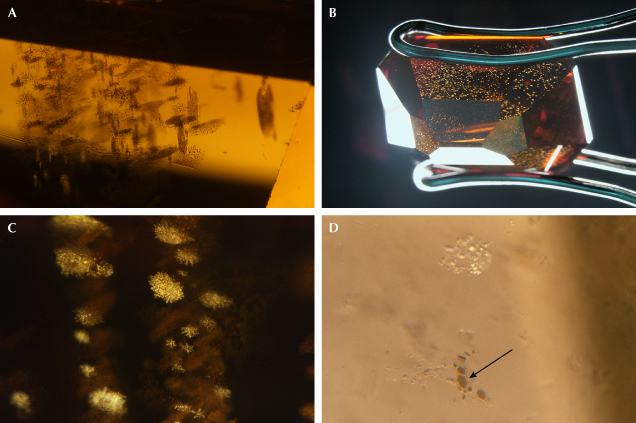

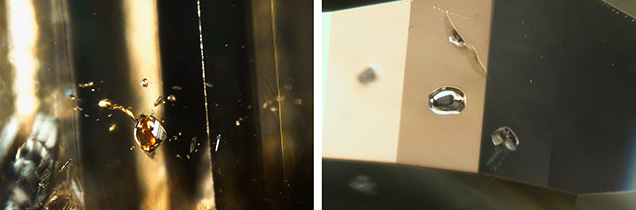

Inclusions. Clusters of dark inclusions are often observed in 480 nm band diamonds under the microscope (figure 6). The clusters are usually oriented in three directions and appear highly reflective when viewed at certain angles. Within each cluster, the dark inclusions are generally less than 10 μm and extremely thin, either with rounded or well-defined hexagonal shapes (figure 6D). Notably, these inclusions are unique to 480 nm band diamonds and are a diagnostic identification criterion. In 480 nm band diamonds with noticeable color zoning, such as those with a combination of colorless or near-colorless and yellow color zones, these micrometer-sized inclusions are observed only in zones with yellow color. Since the 480 nm absorption band is detected only in the yellow color regions in these zoned diamonds, the absence of the micrometer-sized dark inclusions in the colorless or near-colorless regions indicates that these inclusions are likely associated with the formation of the structural defects responsible for the 480 nm absorption band.

The micrometer-sized dark inclusions are very similar to those observed in brown diamonds containing carbon dioxide (Hainschwang et al., 2008, 2020; Barannik et al., 2021; Shiryaev et al., 2023; Lai and Schwartz, 2023) (figure 7). Diamonds containing carbon dioxide are rarely encountered in the gem trade, and only five have been submitted to GIA for analysis since 2022. These brown carbon dioxide–bearing diamonds have a much higher density of dark inclusions, which tend to be larger (up to 50 μm) than those observed in 480 nm band diamonds lacking detectable carbon dioxide. In one of these carbon dioxide–bearing diamonds analyzed by the author, the largest dark inclusions were identified as graphite (or graphene layers), with a characteristic Raman peak at 1583 cm–1, consistent with the analytical result obtained with transmission electron microscopy on similar inclusions from brown carbon dioxide–bearing diamonds from a previous study (Shiryaev et al., 2023). Apart from having clusters of micrometer-sized graphite inclusions, these carbon dioxide–bearing brown diamonds also produce yellow fluorescence in response to long-wave UV, as well as surface fluorescence patterns (excited by deep-UV with wavelengths <230 nm) and spectroscopic features closely resembling those of typical 480 nm band diamonds, which will be discussed in the following section. The similarity in gemological and spectroscopic features suggests a possible genetic relationship between brown carbon dioxide–bearing diamonds and typical 480 nm band diamonds (Hainschwang et al., 2008; Lai and Schwartz, 2023).

ADVANCED GEMOLOGICAL TESTING

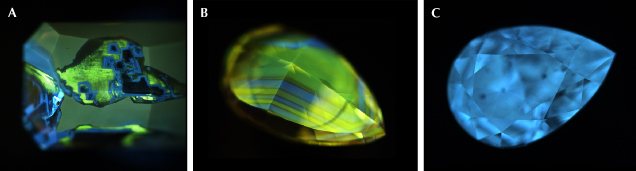

Surface Fluorescence Imaging. The DiamondView instrument is commonly used in gemological laboratories for surface fluorescence imaging of diamonds. The system uses a deep-UV light source. Since the energy of this light source is similar to or greater than diamond’s intrinsic band gap, diamonds strongly absorb the deep-UV light and generate fluorescence very close to the surface, thus producing surface fluorescence patterns that reveal the growth texture (Welbourn et al., 1996).

Most 480 nm band diamonds have irregular surface fluorescence patterns composed of blocky zones (figure 8A). In these diamonds, the dominant fluorescence color is generally yellow or greenish yellow associated with the 480 nm absorption band, with blocky blue fluorescence zones associated with the N3 defect. These blocky zones can have sharp or diffuse boundaries, and the sharp boundaries may be inert to UV and appear as dark rims. Clusters of quadrilateral blocks are occasionally observed within the blue fluorescence zones. Intersecting lines of bright green fluorescence (attributed to the H3 defect) often occur with the blue fluorescence zones.

Another type of surface fluorescence pattern often observed in 480 nm band diamonds is characterized by alternating blue and yellow (or greenish yellow) fluorescence bands, either throughout the entire diamond or limited to a small region (figure 8B). Similar to the blocky type, these fluorescence bands may have sharp boundaries with thin dark lines between the blue and yellow fluorescence zones. The thickness of the alternating fluorescence bands varies within diamonds.

Some 480 nm band diamonds may not have clear surface fluorescence zoning. Most diamonds in this category appear to have evenly distributed blue (figure 8C), yellow, or greenish yellow fluorescence, and a small number of them have orange fluorescence. Generally, blue fluorescence is more frequently observed in chameleon diamonds, whereas yellow or greenish yellow fluorescence is more common for non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Absorption Spectroscopy. At GIA’s laboratories, the infrared absorption features of faceted diamonds are usually detected using an FTIR spectrometer equipped with a diffuse reflectance (DRIFTS) accessory. This bulk analytical technique measures the integrated absorption signal of a diamond. Nitrogen is detected in all 480 nm band diamonds; thus, they are classified as type I (i.e., nitrogen-bearing). Both single substitutional nitrogen atoms (i.e., C-centers, with characteristic absorption peaks at 1130 and 1344 cm–1, commonly accompanied by minor absorption peaks at 1353, 1358, and 1363 cm–1) and nitrogen aggregates in the forms of nitrogen pairs (i.e., A-centers, with representative absorption peak at 1282 cm–1) and groups of four nitrogen atoms around a vacancy (i.e., B-centers, with representative absorption peak at 1175 cm–1) have been observed in these diamonds (Breeding and Shigley, 2009). However, the nitrogen aggregation states in 480 nm band diamonds are usually low, where A-centers (the less aggregated form) are more abundant, and the proportions of B-centers (the more aggregated form) generally do not exceed 45% relative to the total concentration of A-, B-, and C-centers (Lai et al., 2024a). Platelets (i.e., aggregates of interstitial carbon atoms that possibly also contain nitrogen atoms; Woods, 1986; Gu et al., 2020) are occasionally detected in these diamonds, with an absorption peak in the range of 1353–1370 cm–1.

The total concentrations of A-, B-, and C-centers in 480 nm band diamonds are usually low to moderate, typically lower than 300 ppma, calculated based on the integrated nitrogen absorption of the entire diamond (Lai et al., 2024a), although some growth zones may have significantly higher concentrations of these nitrogen defects than others due to the diamonds’ highly heterogeneous defect distribution. Many 480 nm band diamonds have an irregular one-phonon region (400–1332 cm–1) where they show an unusual absorption band (centered at about 1145–1150 cm–1) (Hainschwang et al., 2012) in addition to the A-, B-, or C-centers (figure 9, green and blue lines). The origin of this additional absorption feature has not been determined, but it was previously observed in some diamonds containing C-centers and referred to as the Y-center (Hainschwang et al., 2012). Notably, non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds tend to have a more distorted one-phonon region compared to chameleon diamonds (figure 9). Within the one-phonon region, a peak at 1238 cm–1 is also frequently observed, which might be correlated with the 480 nm absorption band (Collins and Mohammed, 1982).

Occasionally, an absorption band centered at 1424–1445 cm–1 is coupled with two adjacent bands at 1537–1556 and 1574–1591 cm–1 in 480 nm band diamonds (figure 9, blue line), all of which have been suggested to be hydrogen-related, but the structure of the defect has not been determined (Hainschwang et al., 2005). A hydrogen-related defect (N3VH0; three nitrogen atoms adjacent to a vacancy and a hydrogen atom), with the characteristic absorption peak at 3107 cm–1 and the associated absorption at 1405 cm–1 (Goss et al., 2014), is detected in all 480 nm band diamonds. Apart from the 3107 cm–1 peak, a series of hydrogen-related absorptions with low intensities is detected in the spectral range beyond 2700 cm–1 (Fritsch et al., 2007b; Day et al., 2024). Compared to chameleon diamonds, non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds, especially those with detectable single substitutional nitrogen, tend to have more hydrogen-related peaks in the range of 3100–3400 cm–1 (Lai et al., 2024a). Hence, most of these peaks might be associated with hydrogen-related defects comprising single substitutional nitrogen, which become unstable when isolated nitrogen atoms proceed to form nitrogen aggregates, as they are observed only in diamonds with single substitutional nitrogen (Hainschwang et al., 2012; Breeding et al., 2020; Day et al., 2024).

Visible/Near-Infrared (Vis-NIR) Absorption Spectroscopy. Apart from the characteristic broad absorption band centered at around 480 nm, a rare group of 480 nm band diamonds show oscillatory absorption features in the Vis-NIR spectrum (figure 10, red line), which may contribute to their bodycolor. These diamonds have two series of absorption peaks that exhibit an oscillatory pattern in the range of 600–750 nm. The most prominent peaks are 610, 618, 626, and 634 nm (approximately 26 meV apart) in the first series, and 686, 694, 702, 711, and 719 nm (approximately 21 meV apart) in the second series. Between these two series, absorption peaks with much lower intensities may also be detected in some 480 nm band diamonds in this group (figure 10, red line). Relatively strong absorption peaks at 870 and 892 nm almost always accompany the oscillatory features. These oscillatory features have been previously reported for only 10 natural green to yellow diamonds (some of which are likely 480 nm band diamonds based on their FTIR and UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra) among thousands of colored diamonds analyzed, again highlighting their scarcity (Reinitz et al., 1998). Most 480 nm band diamonds in this category show medium to strong orange fluorescence to long-wave UV and medium to strong yellow or orange fluorescence to short-wave UV; a few diamonds show strong yellow fluorescence to long-wave UV and weak to medium yellow fluorescence to short-wave UV.

Another absorption feature that has been observed, yet is also uncommon in 480 nm band diamonds, is an asymmetrical broad band extending from 600 to 730 nm, centered at approximately 685 nm (figure 10, black line). The 685 nm broad absorption band has been attributed to nickel-related defects and frequently occurs with the absorption peak at 883 nm (Lawson and Kanda, 1993; Wang et al., 2007; Dobrinets et al., 2013). The 883 nm absorption peak corresponds to the well-documented 1.4 eV optical center attributed to a defect comprising an interstitial nickel at the center of a di-vacancy (i.e., a pair of vacancies) in the diamond structure (Iakoubovskii and Davies, 2004; Thiering and Gali, 2021). Another nickel-related absorption feature that has been detected along with the 685 nm band is the peak at 794 nm, attributed to a defect comprising nickel in a di-vacancy position surrounded by four nitrogen atoms (Nadolinny et al., 1999). Point defects in the diamond structure that absorb light generally also emit light at an identical wavelength, corresponding to a spectral feature known as the zero-phonon line (ZPL) (see review by Green et al., 2022). The 794 and 883 nm peaks are both ZPLs; thus, they can also be detected with photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy as luminescence peaks, with the 883 nm peak resolvable as the 883/885 nm doublet in PL spectra (Wang et al., 2007).

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy. The majority of 480 nm band diamonds have a highly heterogeneous distribution of structural defects, as revealed by their surface fluorescence patterns with distinct zones (again, see figure 8A). Blue fluorescence zones are not directly associated with the 480 nm absorption band, and in many cases, they correspond to the much paler colored or near-colorless zones of 480 nm band diamonds (figure 11). Typically, the most prominent PL feature detected within blue fluorescence zones is the N3 center with a ZPL at 415 nm. In contrast to the blue fluorescence zones, the yellow or greenish yellow fluorescence zones (directly correlated with the 480 nm absorption band) show complex PL spectra, in which approximately 200 PL peaks have been documented (Lai et al., 2024a). The most frequently observed PL features within the yellow or greenish yellow fluorescence zones are reported below, and many of these features are unique to 480 nm band diamonds. As certain peaks can be better resolved by particular laser wavelengths due to selective excitation of defects (Green et al., 2022), the PL features reported here were excited by multiple laser wavelengths, including 455, 532, 633, and 785 nm, which cover a combined PL spectral range of 457–1059 nm.

When 480 nm band diamonds are excited at 455 nm, the most prominent PL peaks include 459, 468, 470, 489, 497, 512, and 518 nm. The 489 and 497 nm peaks are ZPLs of the nickel-related defects, known as the S2 and S3 centers, respectively (Nadolinny and Yelisseyev, 1994). The S2 and S3 centers have the same basic structure of three (for the S2 center) or two (for the S3 center) nitrogen atoms in the first coordination sphere surrounding a nickel ion in the diamond structure (Lang et al., 2004; Yelisseyev and Kanda, 2007).

When 480 nm band diamonds are excited at 532 nm, a broad PL band is always centered at 650–685 nm (figure 12). This broad band is the most crucial feature for the identification of 480 nm band diamonds, as it is the vibronic emission associated with the 480 nm absorption band (Collins and Mohammed, 1982). Typically, the intensity of the broad PL band increases with the 480 nm absorption band and hence tends to be weaker in chameleon diamonds. The PL band is often overlain by small oscillatory bands that have an interval of approximately 10 nm in the 600–690 nm range (figure 12). These oscillatory features are more commonly observed in non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds than in chameleon diamonds. The intense PL band generally also shows a secondary set of oscillatory bands, which are about 3 nm away from the primary oscillatory bands and have lower intensities. Other frequently observed PL peaks excited by a 532 nm laser are 566, 575, 578, 581, and 590 nm.

When 480 nm band diamonds are excited at 633 nm, the commonly detected PL peaks include 677, 688, 699, 759, 783, and 794 nm. The 759 nm peak is a doublet that comprises two adjacent peaks at 758.7 and 759.4 nm, where the 758.7 nm peak is always more intense. The two peaks in this doublet might not be well resolved if the diamond has experienced plastic deformation (evidenced by the presence of deformation lines), in which case the doublet might become a single peak due to peak broadening. Peak broadening occurs in diamond with strain that is often associated with plastic deformation (Lai et al., 2024a,b), and the effect is more severe for peaks associated with vacancy-related defects (Fisher et al., 2006). This suggests that the 759 nm doublet corresponds to a structural defect involving a vacancy. The intensity of the 759 nm doublet is positively correlated with two bands centered at 774 and 791 nm, which are likely the phonon sidebands of the doublet. The peak at 759 nm has been attributed to a nickel-related defect and considered a feature of untreated natural diamonds (Dobrinets et al., 2013).

When 480 nm band diamonds are excited at 785 nm, the most frequently observed PL peaks are 799, 819, 838, 846, 859, 869, and 883/885 nm. The relative intensities between the 799 and 819 nm peaks can potentially be used to classify chameleon and non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds (Lai et al., 2024a; Hardman et al., 2025). Most chameleon diamonds (with a green component) have a relatively stronger 819 nm peak, whereas the non-chameleon 480 nm band diamonds (without a green component) generally have a relatively stronger 799 nm peak, suggesting that the relative intensities between these two peaks may be related to the concentrations of certain structural defects responsible for the bodycolor and thus the color-change property of 480 nm band diamonds. The 838, 846, and 859 nm peaks are strongly correlated with the 819 nm peak; thus, they might all be related to the same defect (Lai et al., 2024a).

OCCURRENCE OF 480 NM ABSORPTION BAND WITHIN SMALL YELLOW COLOR ZONES

Irregularly shaped or cuboid yellow color zones caused by the 480 nm absorption band have been observed in several colorless and pink diamonds (figure 13) (Sohrabi et al., 2023; Lai et al., 2024b; Hardman et al., 2025). In most of these diamonds, the yellow color zones are volumetrically minor compared to the rest of the diamond. Consequently, the 480 nm absorption band is usually not detected when the bulk diamond is measured using Vis-NIR absorption spectroscopy. Instead, PL spectroscopy is a highly sensitive in situ technique that has been used to confirm that the yellow color zones in these diamonds contain PL features associated with the 480 nm absorption band (Lai et al., 2024b; Hardman et al., 2025).

Similar to typical 480 nm band diamonds, yellow color zones in colorless and pink diamonds have medium to strong yellow fluorescence when exposed to long-wave UV, whereas the colorless or pink color zones have blue fluorescence (figure 13). When examined with the DiamondView instrument, yellow color zones generally show much weaker yellow fluorescence compared to that produced by long-wave UV. This is partly because the yellow color zones are small and/or are only partially located on the surface of these diamonds; occasionally the yellow color zones are completely beneath the diamonds’ surfaces, in which case a yellow fluorescence response cannot be detected by surface fluorescence imaging using the DiamondView. For diamonds with subsurface yellow color zones, PL depth profiling (collecting PL spectra as a function of depth) has demonstrated the ability to detect the zone where the PL features associated with the 480 nm absorption band are the strongest, hence estimating the depth and thickness of the yellow color zones (Lai et al., 2024b). The occurrence of diamonds containing yellow color zones further emphasizes the dynamic environments in which 480 nm band diamonds may grow.

SOURCES

The global abundance and distribution of 480 nm band diamonds are presently unknown. These diamonds are not commonly reported by the mining industry or geological research fields, due in part to their scarcity (and that they are not found in all diamond mines) and/or that these industries are not aware of their features. To date, only two localities are confirmed to produce 480 nm band diamonds: the Chidliak kimberlite field in Canada (Lai et al., 2020) and the kimberlites of the Siberian Platform in Russia (Titkov et al., 2014). Other localities that likely also contain 480 nm band diamonds are Botswana’s Orapa kimberlite cluster (Timmerman et al., 2018) and Canada’s Lake Timiskaming kimberlite cluster (Van Rythoven et al., 2022), based on the interpretation of FTIR spectra and surface fluorescence patterns of the reported yellow diamonds from these localities that are similar to 480 nm band diamonds.

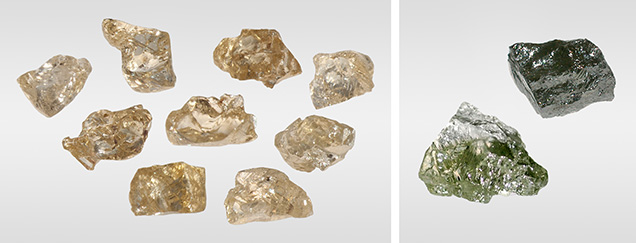

MORPHOLOGY OF ROUGH 480 NM BAND DIAMONDS

Rough 480 nm band diamonds commonly have irregular morphology, lacking any well-defined octahedral or cuboid crystal faces. This morphological characteristic is observed among 480 nm band diamonds from the Chidliak kimberlite field in Canada (figure 14, left) (Lai et al., 2020). Over the past few years, GIA has received several rough 480 nm band diamonds, including chameleon diamonds, for analysis (figure 14, right). Similar to the Chidliak diamonds, none showed any well-defined octahedral or cuboid crystal faces. Another submitted rough diamond exhibited both trigons and tetragons on the same face (figure 15). Trigons and tetragons are etched features restricted to the octahedral and cuboid crystal faces, respectively, formed on the surface of diamond from the interaction with fluids in Earth’s mantle or during kimberlite eruption. This suggests that the diamond has a combination of octahedral and cuboid growth habits, probably resulting from crystallization under dynamic geological conditions. While most 480 nm band diamonds submitted to GIA are faceted and hence the original morphologies are unknown, occasionally etch features are preserved within indented naturals, which reveal the growth habits of these diamonds (e.g., Lai and Hardman, 2023).

MINERAL INCLUSIONS

Often minerals from mantle rocks are encapsulated by diamonds during growth. These mineral inclusions can be used to interpret the mantle rock from which they were derived, and hence the rock in which the diamond may have grown. Mineral inclusions observed in 480 nm band diamonds include pyrope-almandine-grossular garnet, omphacite, rutile, graphite, and sulfide minerals. Pyrope-almandine-grossular garnet ((Mg,Fe,Ca)3Al2Si3O12), omphacite ((Ca,Na)(Mg,Fe,Al)Si2O6), and rutile (TiO2) are minerals associated with eclogite—a major host rock for diamond in the lithospheric mantle (figure 16). Based on the observation that most, if not all, inclusion-bearing 480 nm band diamonds submitted to GIA are eclogitic, it is inferred that these diamonds are more likely to be found in mines that predominantly produce eclogitic diamonds. However, this does not preclude the possibility that 480 nm band diamonds can also form in peridotite—another major diamond host rock in the lithospheric mantle comprised predominantly of olivine ((Fe,Mg)2SiO4), orthopyroxene ((Mg,Fe)2Si2O6), and chromium-rich diopside ((Ca,Cr)MgSi2O6).

CONCLUSIONS

Diamonds colored by the 480 nm absorption band have attracted little attention in the mining industry and gem trade, due in part to their scarcity and therefore unfamiliarity with their properties. While most 480 nm band diamonds have a saturated yellow bodycolor similar to that generated by other diamond defects, these diamonds also occur in a variety of additional colors, including the highly sought-after pure orange diamonds and color-change chameleon diamonds.

Rapid diamond screening can be achieved by exposing them to long-wave UV, as 480 nm band diamonds generally emit medium to strong yellow fluorescence, a mixture of yellow and blue fluorescence, or (occasionally) orange fluorescence. The presence of micrometer-sized dark inclusion clusters—identified as graphite—are a diagnostic gemological feature of 480 nm band diamonds. These platy inclusions are extremely thin and highly reflective when viewed at certain angles, with rounded or well-defined hexagonal shapes. Other characteristic features of 480 nm band diamonds include irregular surface fluorescence patterns, anomalous absorption in the one-phonon region of the FTIR spectrum, and a broad PL band centered at 650–685 nm when the diamond is excited by lasers with wavelengths in the range of, for example, 488–532 nm.

Currently, no known commercial treatments or synthetic growth methods can create the defect(s) associated with the 480 nm absorption band or the color-change property associated with chameleon diamonds. However, it is certainly possible to artificially create other defects in 480 nm band diamonds to alter their colors (e.g., laboratory irradiation treatments to produce a green bodycolor); therefore, advanced gemological testing may be required to ensure that the diamonds are naturally colored. Finally, care must be taken when examining colorless or pink diamonds, as small yellow color zones caused by the 480 nm absorption band may occur in these diamonds and affect their color grades.