Pinctada maculata (Pipi) Bead-Cultured Blister Pearls Attached to Their Shells

April 25, 2017

INTRODUCTION

Pinctada maculata is the smallest mollusk of the Pinctada genus, averaging 40 mm at its widest point. The mollusk is found in the Pacific Ocean, including the waters off Penrhyn Island in the northern Cook Islands (Strack, 2001). P. maculata produces small natural pearls, also referred to as “pipi pearls,” ranging from yellow to orange (“golden”), pink, green, white, black, and gray, and commonly ranging from 4 to 5 mm in diameter (Buscher, 1999). Natural blister pearls* are sometimes encountered and are often referred to as “Puku” (Strack, 2001).

This work describes the characteristics of four Pinctada maculata cultured blister pearls (figure 1) originating from Penrhyn Island, the northernmost atoll of the Cook Islands (figure 2). The cultured blister pearls were produced by Mr. Taruia Matara, who also experimented in culturing pearls using Pinctada magaritifera in the waters off Penrhyn Island in the early 1990s. His Pinctada maculata experiments took place in the late 1990s. However, he was unsuccessful with the latter and only a few examples were produced, four of which were donated to GIA by Mr. Umit Koruturk of Australian Pure Pearls in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

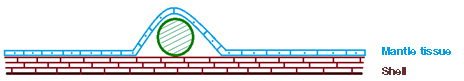

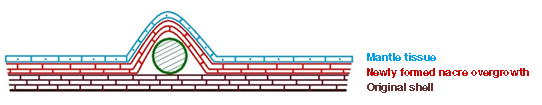

The cultured blister pearls supplied incorporated a freshwater bead as the nucleus. In keeping with the usual cultured blister pearl production procedures, the bead was placed within the shell between the inner shell surface and overlying mantle tissue (figure 3). This allows the epithelium cells in the mantle tissue to secrete nacre over the bead (Strack, 2001; figure 4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We studied four P. maculata shells, with attached bead-cultured blister pearls. The shells measured approximately 49.03 mm x 48.94 mm, 41.51 mm x 40.45 mm, 38.43 mm x 38.53 mm, and 39.05 mm x 35.50 mm, and weighed 12.92, 7.97, 6.74 and 5.42 grams, respectively. We used a number of methods commonly employed in the analysis of pearls to examine the samples. The techniques applied helped determine their identity, the environment in which they formed, possible treatments used, and the possible mollusk origin. A Matrix-FocalSpot XT-3 series real-time X-ray (RTX) machine (voltage 90 kV and current 0.18 mA) fitted with a Toshiba image intensifier was used to identify the nature of the nuclei. A FocalSpot Verifier PF-100 model FSX-PF100 X-ray fluorescence unit (voltage 100 kV and current 3.2 mA ) was then used to provide information about the environment in which the shells and nuclei formed since marine and freshwater materials react differently when exposed to X-rays (Hänni et al., 2005). Finally, a Nikon SMZ18 microscope incorporating NIS-Elements photomicrography software and a Canon G16 camera were used to record the appearance of the samples. The former, together with a GIA binocular gemological microscope, were used to observe any evidence of possible treatments applied, and support some of the conclusions resulting from the other tests.

RESULTS

The shells and their blister pearls were photographed with other shells from the Pinctada genus in order to show the size of the shells in relation to the other species and capture the more obvious external features (figure 5). In theory, cultured pearls have a “newer” appearance than natural pearls, although newly found natural pearls do still appear in the market from time-to-time. Hence the surfaces of most cultured pearls are less likely to be as worn as those of some natural pearls. A pearl’s appearance is also usually related to the appearance of its shell (Southgate and Lucas, 2008). For instance, “golden pearls” mostly originate from mollusks that exhibit a degree of yellow on the shell (Strack, 2001).

This study focused on bead-cultured blister pearls still attached to their hosts. The majority of bead-cultured pearls are round to near-round in shape (Strack, 2001). The samples examined were more baroque to semi-baroque owing to their uneven outlines where they met the shell, but their main bodies were more toward near-round (figure 6).

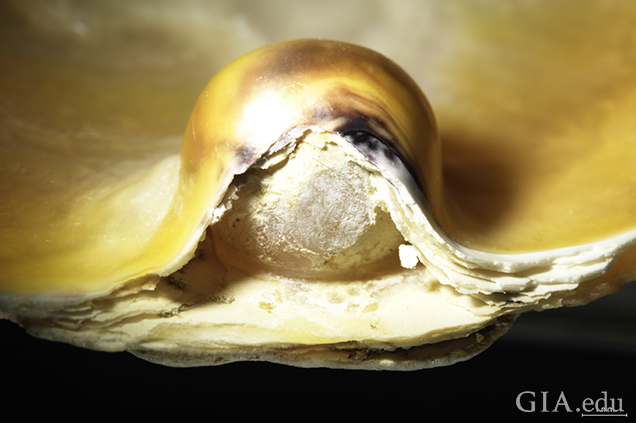

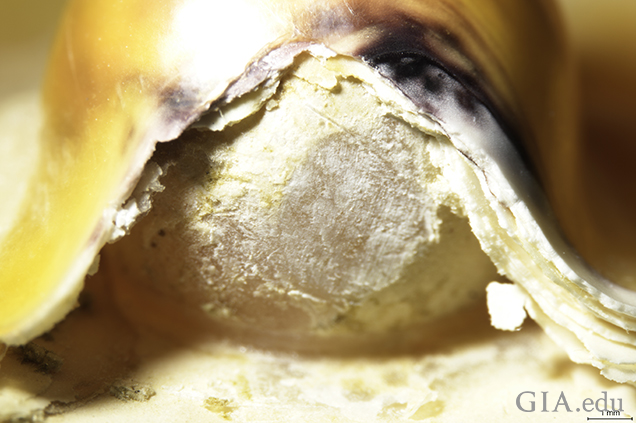

To see the detail more clearly, we employed photomicrography to capture the fine features of the samples. One specimen in particular was of interest: a blister pearl that possessed a large opening between the nacre overgrowth and the host shell, permitting clear observation of the bead nucleus (figure 7 and figure 8).

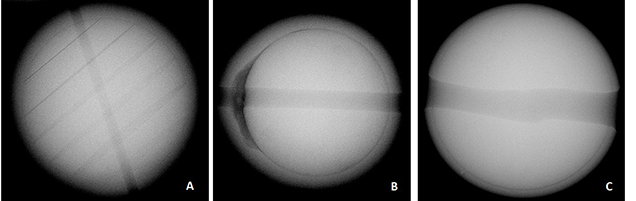

While the external appearance of pearls can be very useful in pearl testing, it is the internal structure that gemologists ultimately need to consider when reaching a conclusion (Sturman, 2009). Various RTX and X-ray computed tomography units exist for this purpose, and when it comes to identifying most bead-cultured pearls the structures are quite obvious. Normally, bead-cultured pearls exhibit a clear demarcation between the bead nucleus and surrounding nacre, while the radio-opacity of the bead nucleus and nacre overgrowth differ (Wehrmeister et al., 2008). In some cases, obvious banding within the shell bead nucleus (figure 9) may be seen when the nucleus is correctly oriented in relation to the detector or, in rare cases these days, the film.

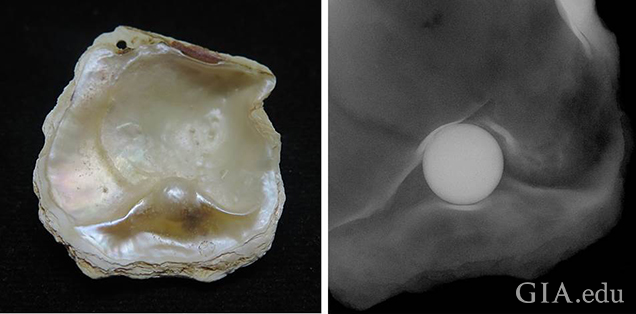

The four samples examined in this study revealed clear demarcations, while the degree of radio-opacity of their beads and that of the surrounding nacre were easy to see. The fact that they are naturally attached to their shells was clearly evident on the RTX images as well. X-ray images captured from side-on (figure 10) proved the nacre covers the bead nucleus of each and blends in with the surface of their shell host without any joints or boundaries that would imply the shell was manipulated. All were clearly naturally attached cultured blister pearls.

When X-rayed in the direction seen in figure 11, a very clear round white shape was visible. This relates to the much greater density (volume of material) the X-rays have to pass through in comparison to the much thinner section of shell. The bead and nacre overgrowth thus show as one form; higher magnification (zoom work) and refocusing, as well as the adjustment of the contrast, would be required to see the boundary between the bead and nacre clearly again.

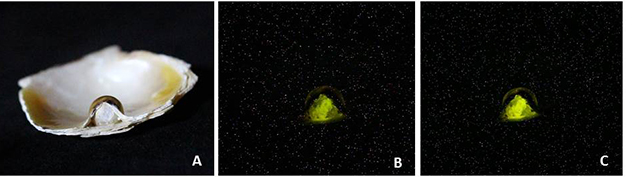

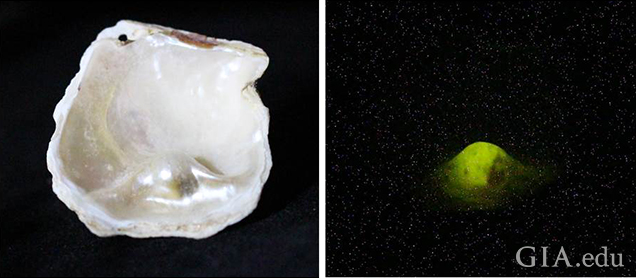

We determined the environment in which the shells and their blister pearls formed using an X-ray fluorescence unit where the results were captured via a camera within the unit. The X-ray fluorescence reactions of two of the samples studied are shown in figure 12 and figure 13, and they reveal a definite variation between the different components. A strong greenish yellow fluorescence was observed emanating from the bead nucleus. The strongest fluorescence comes from the bead nucleus because the vast majority of the cultured pearl industry uses freshwater shell (mostly sourced from the United States) which contains Mn in sufficient quantities to react with the X-rays (Hänni et al., 2005). In the saltwater areas possessing little or no Mn, the lack of a reaction is notable, and this is especially evident in the three images in figure 12, where the exposed bead reacts with an intense greenish yellow glow and the surrounding nacre is mostly inert. The weaker yellowish green fluorescence generally shown by areas of the nacre is due to a partial masking of the bead’s fluorescence by the overlying non-reactive SW nacre.

X-ray fluorescence is a useful test in the arsenal of techniques available to gemological laboratories. The reactions of beads and their pearls can vary according to the thickness of their nacre for two main reasons. The first is the thickness of the nacre overgrowth, and the second is the degree to which the freshwater bead itself fluoresces, since not all beads fluoresce with the same intensity. When considering both points, it should be easy to comprehend that beads with thinner nacre tend to produce a stronger reaction than those with a thicker nacre overgrowth, while a freshwater bead that shows weak fluorescence may show no fluorescence at all if it is surrounded by saltwater nacreous layers that are able to grow thick enough to completely subdue the fluorescence.

CONCLUSIONS

The existence of Pinctada maculata (pipi) bead-cultured blister pearls proves that limited success has been achieved in producing them. Nevertheless, it is also very apparent that we should not expect to see this product in the trade anytime soon. While bead-cultured blister pearls provide an alternative product in the market, they need to be of high quality to be marketable. Unfortunately, the experiments carried out on Pinctada maculata shells in Penrhyn Island did not result in suitably high quality end-products, and so they apparently were discontinued for a variety of reasons. It is very interesting to note that work was carried out to develop such bead-cultured blister pearls, and the results obtained from the scientific analysis of the four samples donated to GIA proved that their identification is straightforward, as is the case with almost all bead-cultured blister pearls. Their distinctive external appearance was the first clue to their identity, as the size of the blister pearls in relation to their small hosts was something perhaps a bit unusual, and of course what appeared to be a bead nucleus on one example visually was later confirmed by RTX, as were the three remaining samples. The RTX work clearly revealed the characteristic round outlines of shell beads used in the culturing process. Finally, the freshwater origin of the bead nuclei, in keeping with the majority of saltwater cultured pearls, was confirmed by observing their luminescence reactions after exposure to X-rays. The information from this study shows that Pinctada maculata bead-cultured blister pearls do exist, but only on an experimental basis. No commercial bead-cultured Pinctada maculata pearls of any kind are known to the authors, even after asking a few individuals involved principally in the trade of natural pearls produced by this, the smallest of all the Pinctada species.

DISCLAIMER

The term “blister pearl” has been applied throughout this article, since such products are often referred to this way in the trade. However, the correct nomenclature should not include the word "pearl" since the objects that formed on these shells are not “pearls” in the strict sense of the word. Blister pearls technically form within a pearl sac in the soft body of the mollusk and then move to the shell, where they are covered by additional nacreous layers.

Mr. Kessrapong and Ms. Lawanwong are analysts in the pearl identification department at GIA in Bangkok. Mr. Sturman is senior manager of global pearl services at GIA in Bangkok.

The authors appreciate the assistance of Mr. Umit Koruturk of Australian Pure Pearls, who donated the samples to GIA, and Ms. Celestine, who provided information on the culturing experiments conducted by Mr. Taruia Matara in the waters around Penrhyn Island.

Buscher E. (1999) Gem News: Natural pearls from the northern Cook Islands. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 147–148.

Hänni H.A., Kiefert L., Giese P. (2005). X-ray luminescence, a valuable test in pearl identification. The Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 5/6, pp. 325–329.

Hänni H.A., Kiefert L., Giese P. (2005). X-ray luminescence, a valuable test in pearl identification. The Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 5/6, pp. 325–329.

Sturman N. (2009) The microradiographic structures of non-bead cultured pearls, https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-NR112009.

Wehrmeister U., Goetz H., Jacob D.E., Soldati A., Xu W., Duschner H., Hofmeister W. (2008) Visualization of the internal structures of cultured pearls by computerized X-ray microtomography. The Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 31, No. 1/2, pp. 15–21.

.jpg)