A Case of Mistaken Identity?

October 20, 2017

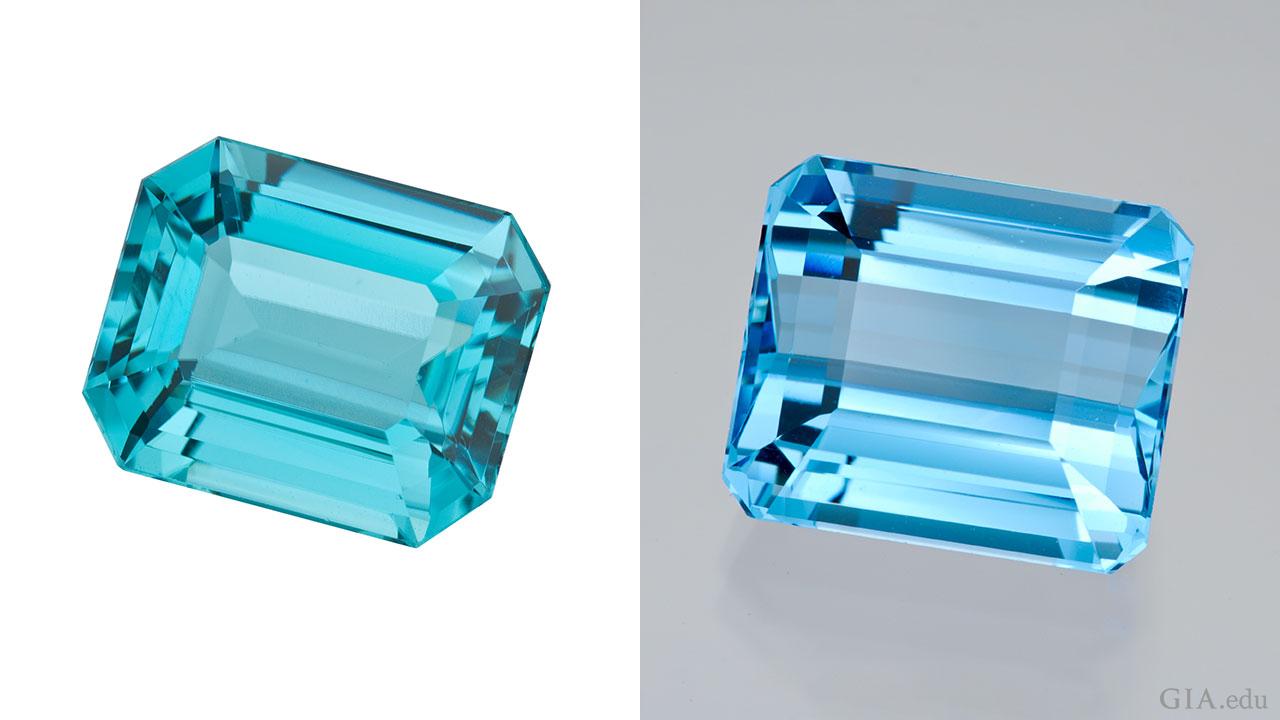

Identifying a gemstone by color alone can lead to a case of mistaken identity, as numerous examples have shown over the course of history.

Take the most famous pretender, the Black Prince’s Ruby, for example. The large crimson, semi-polished crystal the size of an egg first appeared in 14th century Spain when King Pedro of Castille seized it from the Moorish Prince Mohammed of Granada as spoils of battle. It changed hands many times throughout the Medieval era, finally remaining in the possession of several British kings and resides in the Imperial State Crown of England.

But is the famous royal jewel identified as a ruby today?

For fun, let’s engage Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie’s fictional Belgian detective, to investigate the identity of the Black Prince’s ruby and get his opinion.

“Observe the gem under the polarizing filter while I shine a light through the stone. At the same time, I will rotate the filter and turn the stone in several directions to avoid looking down the optic axis. Does the gem blink or change color? No, it does not. Let me explain. If this were a ruby it would blink orangey-red to purplish-red. So you see, this red stone is an imposter! It could be a spinel or red garnet.”

Being a well-read detective, Poirot knew some basic differences between rubies, spinels and garnets. He knew that when light enters a ruby, the light beam will split (double refraction) and leave the ruby as two different colors (pleochroism): orangey-red and violetish-red (dichroic; two colors). But he also knew that there is one direction in a ruby that will appear as one color. In order to see these two colors, he has to look at the stone in at least three different directions. Red spinels and garnets, however, will remain the same color in all directions, which usually means they are singly refractive.

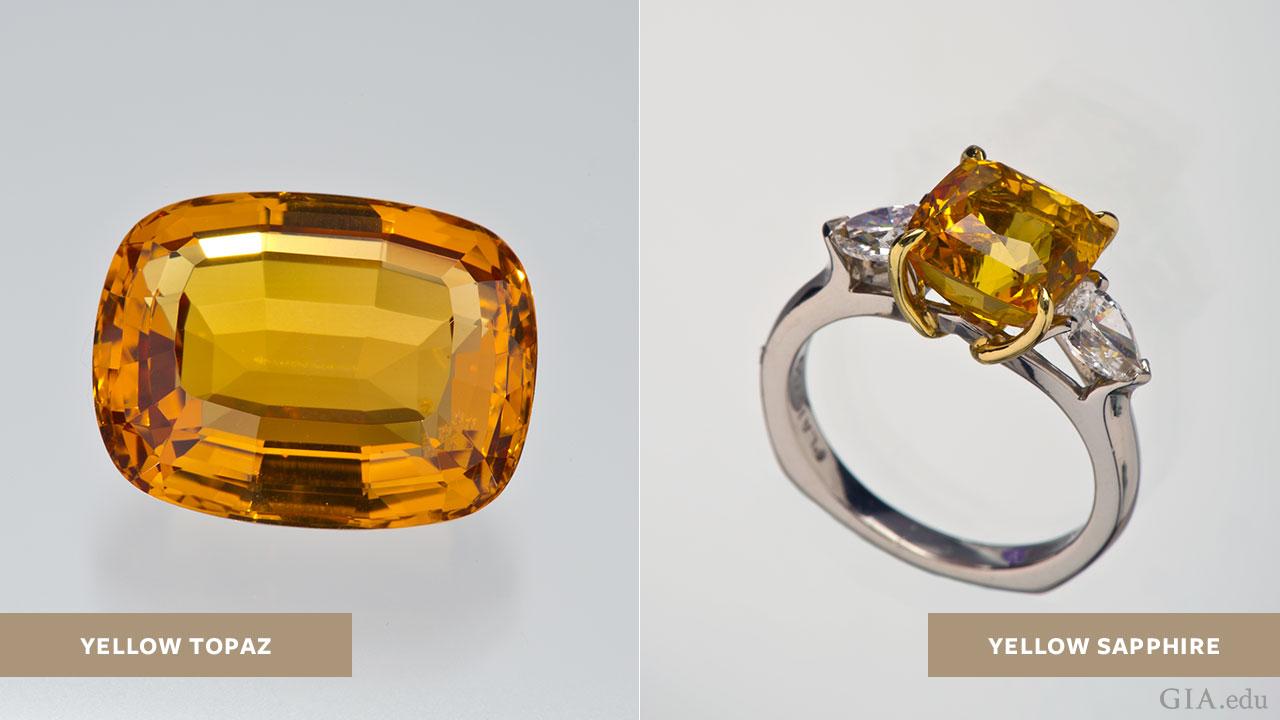

Single refraction in red spinel and garnet is a key factor in separating them from ruby. Double refraction is a key factor for identifying ruby, and sapphire. Emerald, citrine, tourmaline, and topaz can show weak double refraction and require careful testing.

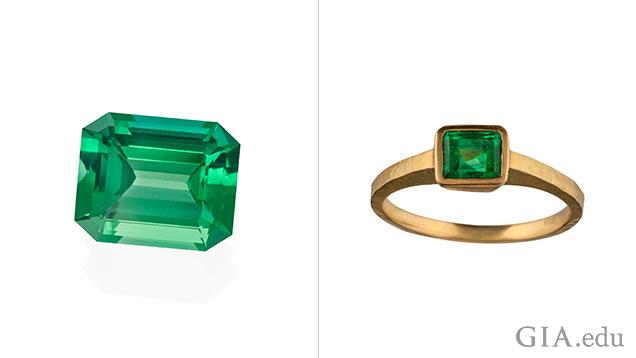

Emerald and tsavorite garnet can appear similar in color. Using the penlight and loupe to look for doubling or pleochroism would separate emerald, which is doubly refractive, from tsavorite, which is singly refractive. Also, emerald’s luster is vitreous (glass-like) to waxy while tsavorite’s is greasy to vitreous.

Determining a gem’s optic character or refraction – along with visual observations of luster, transparency, cut, heft, fracture and phenomenon, if present – are the basics of gem identification.

What Gem is it?

Test your gem knowledge. Can you guess the identity of these gemstones?

Color Can Be Deceiving

There are many characteristics other than color that can give clues to identification.

Inclusions

Visible inclusions using a 10x loupe could also separate emerald from garnet. Garnet usually has fewer inclusions than emerald, but if liquid or two-phase inclusions are present in emerald, they can be an identifying factor.

Separating peridot from demantoid garnet is easier if “lilypad” (unique disc-like liquid and gas inclusions found in peridot), are seen under 10x loupe magnification.

Luster and Opacity

Aventurine quartz and jade appear similar in color, but a close inspection of luster would reveal differences. Jade is dull in comparison to quartz’s vitreous nature.

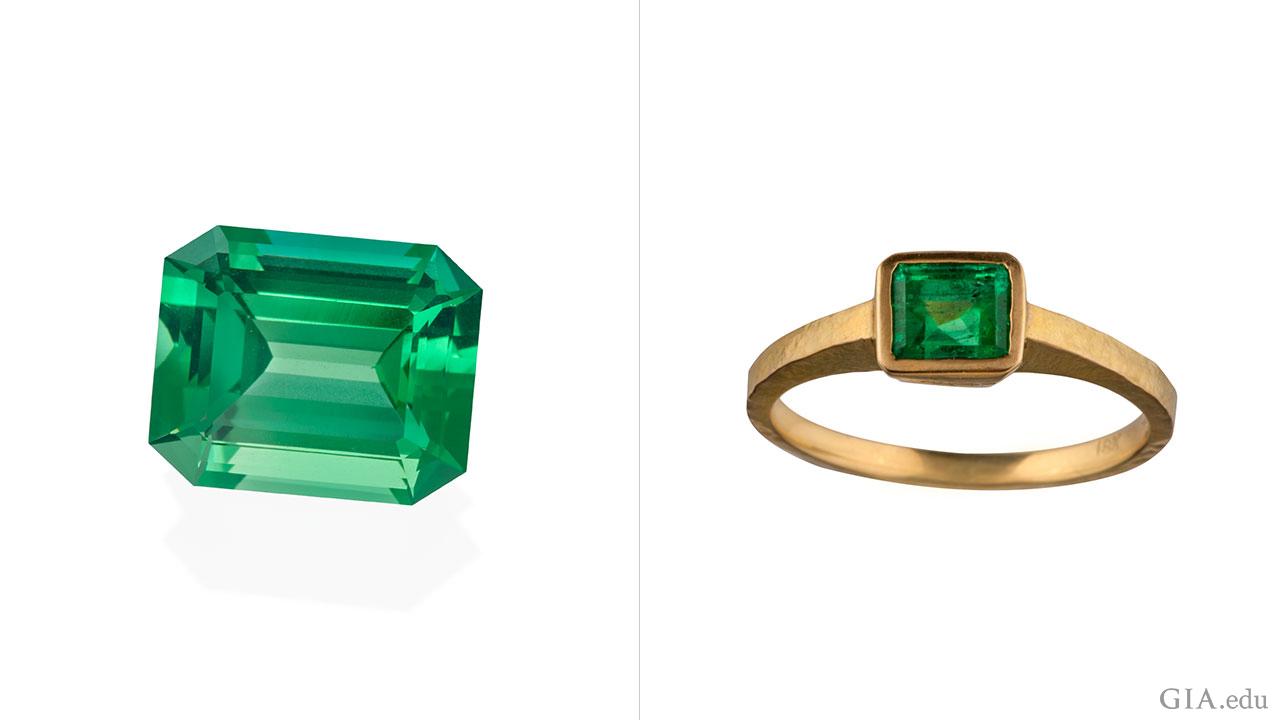

Similar-looking transparent hard stones such as yellow sapphire, topaz, garnet and citrine quartz have a higher luster when polished.

A trained eye can easily see the difference of light reflecting off the surface of the sapphire, which is bright and shiny. Soft stones like yellow opal and amber will be waxy to dull in appearance. Both yellow sapphire and topaz have vitreous luster and are doubly refractive, so, advanced testing would be required to identify these gemstones.

Hardness

Sapphire is very hard, registering 9 on the Mohs hardness scale; topaz is 8; citrine is 7; opal is softer at 5-6½; and amber is softest yet at 2. The amber’s heft is also noticeably lighter than other gems.

Although the instruments are simple, it takes a lot of practical observation and experience to become proficient at making separations. These principles are the foundation of modern gemology and remain at its core today.

Sharon Bohannon, a media editor who researches, catalogs and documents photos, is a GIA GG and GIA AJP. She works in the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center.