An Evaluation of Turquoise from the Mona Lisa Mine in Arkansas

ABSTRACT

Turquoise from the Mona Lisa mine, located in Polk County in the U.S. state of Arkansas, gained renewed interest in 2018 when Avant Mining promoted the re-opening of the mine, displaying an approximately 111 kg stabilized turquoise nugget at the AGTA GemFair in Tucson, Arizona. The unique location and geologic setting of the mine led many to question whether this material was turquoise and how it could have formed. Phosphate minerals are prevalent in Arkansas, but the lack of an obvious copper source in this area was considered an obstacle to turquoise formation. In this study, samples obtained during multiple visits to the mine were analyzed to identify their chemistry and structure. X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry results were obtained and combined with geologic observations and measurements to comprehensively characterize Mona Lisa turquoise. Copper was identified as a major elemental component of all tested samples, with copper oxide concentrations ranging from 1.71 to 6.18 wt.%. The presence of copper in major element amounts warrants the use of the term turquoise in a gemological context, although the broad range of concentrations suggests solid-solution relationships between turquoise-group minerals, highlighting the inherent heterogeneity and complex mineralogy of turquoise deposits.

Few gemstones have a history as extensive and diverse as turquoise. From ancient civilizations in China and the pharaohs of Egypt to modern designers, this opaque gemstone has captured the imagination of cultures and communities everywhere. In the United States, turquoise has long been associated with Native American cultures. While mines across arid regions in Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado, and California have storied histories and archaeological importance, many of these sites today are increasingly depleted. Turquoise remains in great demand, with global and domestic markets placing a premium on stones with recognized mine origins. Although isolated sedimentary turquoise mineralization has been observed and recorded in the U.S. outside the American Southwest, such as in Clay County, Alabama (Harwood and Hajek, 1978), mining those sites has not been economically practical. However, in 2018, a previously inactive turquoise claim—the Mona Lisa mine—in the Ouachita Mountains of western Arkansas was purchased by Avant Mining LLC, and “Mona Lisa turquoise” reentered the marketplace (figures 1–3). Limited information exists about the Mona Lisa mine, leading to skepticism about the mine’s validity as a commercial turquoise source.

The presence of turquoise in western Arkansas had been previously documented (Sinkankas, 1997), but the extent and nature of the deposit had not been fully described. The wetter climate of the Ouachita Mountains (compared to the American Southwest) causes accelerated weathering of phosphate minerals, including turquoise. Arkansas also lacks the past igneous activity and related copper porphyry deposits found in the geology of more commonly known turquoise mining locations. The absence of abundant copper mineralization in Arkansas has led to speculation that the turquoise from the Mona Lisa mine is not turquoise but rather a pale green to blue copper-deficient mineral, planerite, of the turquoise group. Planerite is one of several phosphate minerals frequently found in Arkansas. A more complete mineralogical description and evaluation of the Mona Lisa mine is the focus of this study, to determine whether the material is turquoise. When characterizing turquoise sources, archaeological implications must also be considered. Although there is no record of Mona Lisa turquoise use by indigenous tribes, turquoise artifacts found at regional Caddo archaeological sites in East Texas—which have been attributed to trade with the American Southwest—offer the slight possibility that Mona Lisa turquoise was mined by Native Americans in southwest Arkansas.

This research represents the most comprehensive historical, geological, and mineralogical evaluation of Arkansas’s Mona Lisa mine, with detailed characterization and analyses of material from this source. Multiple trips to the mine from 2020 to 2022 resulted in extensive field observations, mapping, and sample collection. Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques were employed to confirm the identity of the turquoise and its accompanying matrix. Moreover, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) and ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectroscopy were used to identify the chromogenic components and reveal any possible treatment of loose cabochons (which is commonly encountered in turquoise samples). Geochemical data were utilized to identify major element compositions, which were compared to established turquoise-group minerals. The scope of this research increases the understanding of the Mona Lisa mine, a modern source of American turquoise.

HISTORY

In 1877, phosphate minerals in Arkansas were first described from a variscite locality in Montgomery County (Chester, 1877). In 1883, Arkansas wavellite was discovered and reported by George Kunz (1883), and mining for “phosphate rock” in multiple Arkansas counties began in the twentieth century (Stroud et al., 1969). In the years prior to World War II, geoscientists with the Work Progress Administration (WPA) and other government agencies uncovered other aluminum phosphate localities as they explored the potential for manganese resources in western Arkansas (Barwood and deLinde, 1989). The Mona Lisa mine site, located on the ridge of Little Porter Mountain, first opened in 1958 for mining phosphate for agricultural fertilizers. Broader-scale phosphate mining in other Arkansas counties (e.g., Searcy, Van Buren, Independence, Pulaski) decreased the demand for such material, leading to the Mona Lisa site’s closure before 1963 (Stroud et al., 1969). In 1974, the mine was rediscovered by Jack McBride, who reportedly built a cabin near the mine (Wigley, 2006). Later reports indicated that the mine was leased at the time to multiple parties over the course of the year, the rights belonging to McBride, James McBroom, and the Newton Company, Inc., respectively. The mine was known by many names in the 1970s, including “the McBride,” “Newton Company,” “Blue Bird,” “McBroom,” and “Mona Lisa” (Sinkankas, 1997). Prior to 1978, turquoise production involved the use of a simple vertical shaft to intersect the turquoise zone (at a depth of about 9 m), followed by digging horizontal tunnels to find the extent of the deposit (Ericksen et al., 1983). Cumulative turquoise production reportedly did not exceed 272 kg during that period of production (Ericksen et al., 1983).

Charles “Chuck” Mayfield learned of the mine in the late 1970s, filing several claims while prospecting for samples in the area (Smith, 1981). Following the turquoise boom of the 1970s, Mayfield began mining the turquoise commercially in 1981 (Fellone, 1983). At this time, Jack Wigley, a construction contractor from Dallas, Texas, became involved with the operation, working with a backhoe and limited blasting in addition to hand tools. By 1982, both Wigley and Mayfield had described the discovery of an enormous turquoise nugget weighing approximately 172 kg. During this initial period, some turquoise from the mine was accurately marketed as “Arkansas turquoise” (figure 4), while the material was also sold as “Southwestern turquoise,” resulting in difficulty evaluating the true amount and value of production from the Mona Lisa mine (Archuleta and Renfro, 2018). Wigley (2006) stated that his unfamiliarity with turquoise mining led to significant material being lost; lower-grade material was simply discarded when it could have been impregnated to allow cutting and polishing. Increased competition from other sources in the U.S. turquoise market caused operations to close in 1986, and further reports suggested that the open trench had been “mined out.” Interestingly, neither Wigley nor Mayfield mentioned each other by name in their respective reports from the site, although it appears they mined turquoise at the Mona Lisa mine during the same time period. From 1989 to 1991, the mine was reclaimed by the National Forest Service (Laney, 2020), and it remained inactive for more than two decades, serving only as a minor collecting locality for informed rockhounds.

In 2017, James Zigras, founder and owner of Avant Mining LLC, purchased the mining claim and leased the subsurface mineral rights from the Bureau of Land Management (Targeted News Service, 2020) where the mine is located in the Ouachita National Forest. A test trench in early 2018 produced 454 kg of turquoise within one week (Archuleta and Renfro, 2018), an amount that encouraged further development. Avant Mining promoted the re-opening of the mine at the 2018 AGTA GemFair in Tucson, Arizona, displaying the extremely large rough turquoise nugget found in the early 1980s. Unearthed at 172 kg, the nugget has since been polymer impregnated and polished, currently weighing 111 kg and touted as the “largest American turquoise nugget ever discovered” (figure 5). Since its reentry into the market, the Mona Lisa mine has been operating sporadically, with minor interruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, inclement weather, and delayed access to equipment. Avant Mining has continued to uncover new areas of turquoise mineralization and occasionally offers fee digs, allowing rockhounds and collectors to visit the site.

CLIMATE AND GEOLOGY

While turquoise is found in varying climates around the world, the climate at the Mona Lisa mine distinctly contrasts with the arid climates in the turquoise mining districts of the American Southwest. The Ouachita Mountains’ hilly terrain is characterized as temperate (humid subtropical), with most precipitation in the fall and spring. Total precipitation averages around 150 cm per year in the town of Mena (Polk County seat), roughly 22 km northwest of the mine (U.S. Climate Data, 2022). The annual mean temperature in the Mena area is 16°C (60.8°F), the result of hot summers and mild winters. The plant growth on the mountain ridges is dependent on exposure to sunlight, with some areas densely forested (e.g., shortleaf pines, various hardwoods) and others sparsely.

The Mona Lisa mine currently consists of an approximately 90-meter-long open trench (figure 6) dug into weathered and fractured host rock along the ridge of Little Porter Mountain in Polk County, Arkansas. The trench is located near the contact and transition between the Missouri Mountain Shale and Arkansas Novaculite, with thin beds of shale visible just south of the trench and interbedded in novaculite within the trench.

Arkansas’s Late Devonian to Early Mississippian Novaculite Formation (figure 7) consists of multicolor high-purity cryptocrystalline silica that derives its name from the Latin for “razor” due to the prevalent usage of the material for whetstones (Goldstein, 1959). Novaculite is differentiated from chert by its lighter color, lack of lamination and chalcedony, and less organic and clastic material (Goldstein, 1959). The deposition of the Arkansas Novaculite remains a complicated geologic topic, with fossil remains of radiolaria, spores, and sponge spicules offering some evidence that the silica was derived organically (Goldstein, 1959). However, elemental concentrations of the rock show a reasonable resemblance to that of a magmatic body associated with arc volcanism, caused by the deposition of siliceous volcanic ash into the ocean (Philbrick, 2016).

The Early-Middle Paleozoic rocks found in the Ouachita Mountains record the rifting along the southern margin of the North American craton, the beginnings of a complete Wilson Cycle—regressing and transgressing coasts. During the Late Paleozoic, the closing of the ocean basin began, starting with collision in the east—the Appalachian Orogeny—between the North American craton and the African plate (Gutschick and Sandberg, 1983). As this impact continued, an accretionary wedge was thrust on top of the subducting plate, causing extensive faulting and folding (Houseknecht and Matthews, 1985). The brittle deformation provided the means of transport for mineralized veins to form, with radiometric dating of adularia (a variety of potassium feldspar) in the veins confirming Late Pennsylvanian to Early Permian deformation and development (Richards et al., 2002). This tectonic activity during the Ouachita Orogeny (~318 to 271 Mya; figure 8) provided the setting for the unique geologic conditions that facilitated the mobilization and mineralization of phosphates such as turquoise.

Turquoise-Group Minerals. For this study, it was crucial to distinguish between multiple mineral species that may share similar properties and to define turquoise accurately. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Mössbauer spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy have been previously used to analyze the crystallography and chemistry of turquoise (Foord and Taggart, 1998; Frost et al., 2006; Abdu et al., 2011). Prior research on turquoise and related phosphate minerals led to the establishment of the mineralogic turquoise group—a set of turquoise and five similar minerals with minor chemical differences (Foord and Taggart, 1998).

The turquoise group is comprised of turquoise (CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O), planerite (Al6(PO4)2(PO3OH)2(OH)8•4H2O), chalcosiderite (CuFe3+6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O), faustite (ZnAl6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O), aheylite ((Fe2+,Zn)Al6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O), and an unnamed iron-bearing end member (Fe2+Fe3+6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O). These mineral species are isostructural, with limited differences in unit cell dimensions. The general chemical formula for the turquoise-group minerals is commonly expressed as A0-1B6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O (Abdu et al., 2011). The A site is occupied by divalent cations, typically Cu2+, Zn2+, and/or Fe2+, while the B site houses the trivalent cations Al3+ or Fe3+. The range in metal compositions at the A and B sites is responsible for variation in color in turquoise-group minerals (Abdu et al., 2011). All members of the turquoise group form in the triclinic crystal system, representing the space group P1, with the only symmetrical element being a point of inversion. Focusing on the crystallography of turquoise-group minerals requires additional nomenclature to describe the structural relationships between the chemical components.

The turquoise-group formula that best represents the crystal structure of the unit cell is X(M12M22M32)Σ=6(PO4)4(OH)8•4H2O. The structural formula differentiates the positions of the four octahedrally coordinated cation sites. The X, M1, M2, and M3 crystallographic sites are coordinated by oxygen and hydroxide anions. The tetrahedral anionic phosphate groups, characteristic of all phosphate minerals, share corners with the M1 and M2 sites, extending in the crystallographic b direction (Abdu et al., 2011). The X octahedra shares an edge with the M1 and M2, while shared corners between the tetrahedral phosphate and the M3 site extend the motif in the a and c directions (figure 9). The structure is additionally strengthened by hydrogen bonds between (OH)– groups (Abdu et al., 2011). Resulting from this structure, the X site and the M3 site’s differences in spatial arrangement from the M1 and M2 sites permit the substitution of certain elements in particular locations; the X site accepts divalent cations with intermediate ionic radii (Cu2+, Zn2+, Fe2+), as the M sites accept trivalent cations with smaller radii (Al3+, Fe3+), with M3 preferring more frequent substitutions (Abdu et al., 2011). Strict compositional boundaries between turquoise-group end members have not been explicitly defined. Due to solid-solution relationships and the typical micro- to cryptocrystalline nature of turquoise-group minerals, chemical analyses frequently demonstrate heterogeneity and intermediate compositions. Defining compositional boundaries between end members can be complex: the prevalence of site vacancies must be determined for planerite, and the oxidation state of iron must be considered for aheylite and chalcosiderite. As faustite and turquoise differ by their X-site occupancy, using the zinc-to-copper ratio can more directly discriminate between the two.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

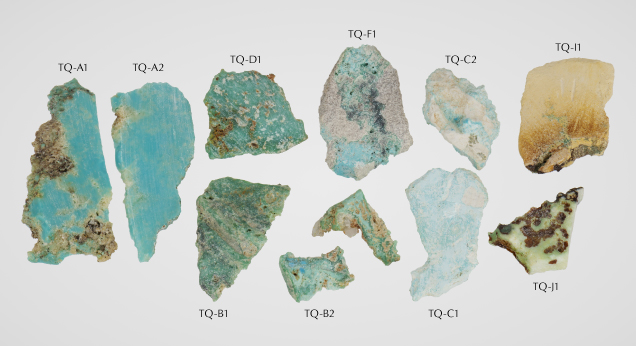

Samples. Ten natural turquoise samples with matrix components were donated by Avant Mining for analysis (TQ-A1 through TQ-J1; figure 10). The author selected these samples from an array of material produced by the test trench and found in old mine tailings. Samples were selected intentionally to encompass the range of material found at the mine, with differences in color and hardness (table 1). Based on GIA’s colored stone reference collection classification scheme, these samples are C type, collected on-site from the miners (Vertriest et al., 2019). Samples were also collected directly by the author (A type) but were generally too small for full analysis using the methods outlined in this study. Avant Mining also supplied six polymer-impregnated turquoise cabochons (ML-01 through ML-06) and a polymer-impregnated turquoise and matrix slab, demonstrating stabilized examples of the material now available on the market (figure 11). Stabilization refers to the process of impregnating turquoise with polymer, resin, or wax, which can improve the color and usability of a specimen.

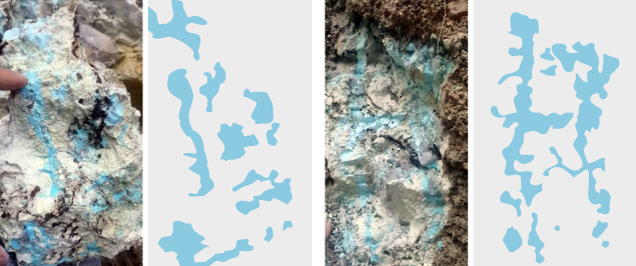

Fieldwork. Several field expeditions to the Mona Lisa mine were conducted from 2020 to 2022. To represent the scale of the mine, Thomas R. Paradise, professor of geosciences at the University of Arkansas, and the author constructed an isohypsometric (relative elevation) map from a false datum outside the mine trench. The spatial relationships were preserved using tape measures, Abney and laser levels, and a 10-meter stadia rod. Changes in rock type and widespread fracturing of the host rock were observed. The bedding orientations of the geologic formations were recorded using Brunton compasses and the Stereonet Mobile application (Allmendinger et al., 2017). At the time of the visits, the mine was inactive, and little in situ turquoise was observable. Turquoise mineralization patterns in the trench suggested the turquoise formed in preexisting fractures and voids in the host rock (figure 12). Therefore, the existing fractures in the host Arkansas Novaculite formation represented the most efficient channels for mineralization. Gregory Dumond, associate professor of geosciences at the University of Arkansas, and the author measured the orientations of more than 200 fractures within the Mona Lisa mine trench.

Physical Properties. Sample colors were recorded under daylight-equivalent lighting. Hardnesses were determined using Mohs hardness pencils calibrated to every 0.5 unit on the Mohs hardness scale.

UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy. UV-Vis-NIR spectra were collected on untreated and treated samples at GIA in Carlsbad, California, using a GIA UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer in the 250–985 nm wavelength range. Spectra were recorded in a reflective configuration, using a Labsphere certified reflectance standard for establishing the background. Three averages per analysis were collected, with an integration time of 100 ms and resolution bandwidth of 0.7–0.8 nm.

FTIR Spectroscopy. Transmission IR spectra from the six stabilized samples and ten rough untreated samples were collected at GIA with a Thermo Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer over a 600–6500 cm–1 range. The KBr pellet method was used to allow transmission through the samples. Spectral resolution was set at 4 cm–1, with 64 scans per analysis.

X-Ray Diffraction. Ten samples were cut into small slabs and analyzed by Andrian V. Kuchuk from the University of Arkansas Nanocenter for XRD patterns on a Malvern Panalytical X’Pert3 Materials Research Diffractometer. Sample slabs (not powdered samples) were analyzed directly to preserve the specimens. XRD is a quick tool to identify mineral crystal structures; this conventional technique has been used in many turquoise studies due to the link between structure and chemistry (Foord and Taggart, 1998). Samples were scanned between the 5.04° to 50.96° 2θ angles with a step size of 0.015° every 0.6 seconds. The radiation was sourced from a copper anode with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å. The PANalytical X’Pert HighScore mineral software was used to process the data and identify the mineral phases. QUALX2.0 diffraction software (Altomare et al., 2008, 2015) was used to better differentiate sample spectra when they could be compared to crystal structures within public databases (e.g., POW_COD; Gražulis et al., 2012; Altomare et al., 2015). Peaks were matched with the dominant crystal phases after background correction based on figure of merit of the database entries.

Raman Spectroscopy. Raman analysis was conducted by the author at Baylor University in Texas using a Thermo Scientific DXR Raman microscope fitted with a 10× objective, 532 nm laser, 25 μm pinhole, and 1800 lines/mm grating. Analyses were conducted at room temperature (~21°C) with a spot size of 2.1 μm. As documented in other Raman studies of turquoise, fluorescence correction was applied with adjusted laser power (from 8.0 to 1.0 mW) to account for peak saturation and to limit disturbances (Dumańska‐Słowik et al., 2020). In previous research, the Raman signature of turquoise was mapped by Frost et al. (2006), Čejka et al. (2015), and Dumańska‐Słowik et al. (2020), whereby each vibrational mode can be attributed to types of bonding within the turquoise sample. Then the RRUFF library (Lafuente et al., 2015) was queried for reference spectra to compare with the Mona Lisa material.

Geochemistry. Two natural turquoise samples were chemically analyzed by laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) at GIA. Samples TQ-C1 and TQ-D1 were selected for analysis for their differing appearances, confirmed identities by Raman and XRD as members of the turquoise group, and suitability for the methodology (chalkier samples caused issues with establishing a clean background in the sample chamber). The system links a Thermo Fisher iCAP Qc ICP-MS with an Elemental Scientific Lasers 213 nm laser. Three spots measuring 55 μm in diameter were collected on two samples with a fluence of ~10 J/cm2 and a 10 Hz repetition rate. Spot locations were chosen on areas of the samples with minimal visible matrix influence. Two samples of untreated Sleeping Beauty turquoise (Globe, Arizona), donated by the Turquoise Museum (Albuquerque, New Mexico), were also analyzed to directly compare Mona Lisa mine material with turquoise from a well-known source. Three external standards—NIST 610, GSD-1G, and GSE-1G—were used in conjunction with 27Al as an internal standard. Ideal turquoise phosphorus concentrations (P2O5 = 34.90 wt.%) were assumed during data processing according to stoichiometric calculations. The data was then converted to wt.% oxides in order to view major element concentrations. Varying oxidation states, especially of iron substituting into turquoise’s formula at multiple sites, complicates the conversion of wt.% data to atoms per formula unit. Due to the imprecise nature of those calculations based on LA-ICP-MS data, the focus here is solely on the oxides and how they relate to the turquoise mineral group.

RESULTS

Gemological Characteristics. Within the Mona Lisa mine trench, the appearance of the material varied from chalky and pale colored (material requiring stabilization) to harder, more saturated greenish blue turquoise (not requiring stabilization). Sample colors ranged from yellowish green to greenish blue (again, see table 1). Samples ranged in hardness from <2.5 for chalky turquoise to 6 for more coherent samples. The hardness of turquoise is generally between 5 and 6 on the Mohs scale.

Example IR spectra (figure 13) display typical turquoise bands based on OH (~3509 cm–1), H2O (~1635 cm–1), and PO4 (~1059 and 1110 cm–1) stretching (band assignments from Čejka et al., 2015). Polymer-impregnated samples were distinguishable from untreated samples by the carbonyl band at ~1732 cm–1. UV-Vis-NIR data from the same samples were collected in the 250–987 cm–1 range and identify the roles of iron and copper in the turquoise’s color (figure 14). The absorption band at ~429 nm is caused by Fe3+, while the broad band centered around 685 nm is a Cu2+ feature (Chen et al., 2012).

Fieldwork. The constructed isohypsometric map and depth model of the Mona Lisa mine are presented in figure 15. The map was constructed using a false datum on the southwestern edge of the trench. Two dominant fracture populations were recorded: steeply westward-dipping (n = 63; average strike and dip: 193.42°, 80.85°) and steeply eastward-dipping (n = 65; average strike and dip: 2.48°, 79.01°). Seam diagrams (figure 16) depicting the patterns of turquoise mineralization within the trench show that the orientation of seams follows these prevalent near-vertical fractures. The turquoise seams, however, are often not continuous. Other minerals within the veins include quartz, iron oxides, and manganese oxides.

Mineralogy Data. Eight of ten samples tested with XRD matched with turquoise-group minerals (five turquoise, two faustite, and one planerite). An example turquoise-matching diffractogram (sample TQ-C1) is shown in figure 17. The other two samples had more dominant diffraction patterns related to the matrix material, which overwhelmed any potential turquoise signal. Nine of the ten samples matched with turquoise-group minerals using Raman spectroscopy (eight turquoise and one planerite). When possible, the matrix material was also tested; identified phases are shown with the complete results in table 1. Samples TQ-A1, TQ-A2, TQ-B1, TQ-B2, TQ-C1 (figure 18), TQ-C2, TQ-D1, and TQ-F1 matched turquoise Raman reference spectra.

Chemical Composition. Three LA-ICP-MS spots each were collected on samples TQ-C1 (greenish blue areas) and TQ-D1 (blue-green areas), which were confirmed as structural turquoise by Raman spectroscopy and XRD. Table 2 contains the major element concentrations in wt.% oxides of these samples, averaged concentrations from the Sleeping Beauty samples, averaged Iranian turquoise chemistry determined by EPMA (Gandomani et al., 2020), and theoretically ideal turquoise chemistry (Foord and Taggart, 1998) for comparison. Values for Al2O3 and P2O5 shown from this study are assumed based on turquoise stoichiometry. The CuO content varies significantly, ranging from 1.71 to 6.18 wt.% in these samples. Iron and zinc readily substitute within the turquoise group; Fe2O3 ranged from 0.55 to 0.87 wt.% and ZnO from 0.029 to 0.34 wt.%. H2O content (calculated as the difference from 100%) was high for sample TQ-D1 (23.37–25.15 wt.%) and lower for TQ-C1 (17.06–18.67 wt.%). CaO was detected with high concentrations (1.33–6.30 wt.%) for TQ-C1, but only in trace amounts for TQ-D1.

DISCUSSION

Mineralogy. Out of the ten Mona Lisa samples tested, seven had conclusive matches with XRD reference patterns for turquoise (again, see figure 17). The other three analyses revealed the presence of crandallite (a calcium aluminum phosphate) and quartz in the matrix material (dominant matrix signal prevented the collection of clear turquoise diffraction patterns for these samples) and identified the pale yellowish green sample slab (TQ-J1) as the turquoise-group mineral planerite. Out of the ten Mona Lisa turquoise samples, nine were identified conclusively as turquoise-group minerals through comparison with the Raman reference spectra from the RRUFF database (again, see figure 18; Lafuente et al., 2015). The presence of copper as a major elemental component differentiates turquoise from all other turquoise-group minerals, which have similar crystallographic dimensions and cannot be easily separated using standard structural testing.

In the turquoise group, solid-solution relationships between mineral end members are common. The substitution of copper, zinc, and vacancies in the X site causes the turquoise-planerite solid-solution series and the probable turquoise-faustite solid-solution series. Concentration data from this study indicated the presence of copper, zinc, and iron as major elements in some samples, with higher average concentrations of copper. However, the highest measured CuO content in this study was 6.18 wt.%, while ideal turquoise would have >9 wt.% (Foord and Taggart, 1998). These lower concentrations indicate that vacancies fill many octahedrally coordinated X sites in Mona Lisa material. Ideal planerite only has vacancies in its X site, with no copper or zinc. Copper has been detected in planerite samples in concentrations up to 3.41 wt.%, while samples with 3.92 wt.% copper have been described mineralogically as an intermediate planerite-turquoise (Foord and Taggart, 1998). The presence of vacancies in Mona Lisa samples provides evidence that the samples are intermediate members of the turquoise-planerite series. Compositional boundaries for the use of the names turquoise and planerite have not been previously defined or characterized. The H2O content of the two tested samples also provides a hint at the planerite-turquoise relationship. A fully occupied X site corresponds to a lower water content for turquoise (~17.72 wt.%), while vacancies correspond to higher water content (~21.56 wt.%) (Foord and Taggart, 1998). Using this relationship, TQ-D1 can be inferred to have fewer occupied X sites than TQ-C1. Iron concentrations were also analyzed, but these concentrations do not distinguish between Fe2+ and Fe3+. Because iron can fill the X site (Fe2+, aheylite) or the M1-3 sites (Fe3+, chalcosiderite), the valence state of the iron is important to consider when evaluating solid-solution relationships between turquoise and iron-bearing turquoise-group minerals. Assuming all iron as Fe3+, Mona Lisa and Sleeping Beauty turquoise compositions were plotted on a ternary diagram (figure 19). Although turquoise from both localities contains iron, it remains chemically much closer to the turquoise end member than the chalcosiderite end member. The major elemental concentrations of iron are interpreted as an indicator of further substitution within the crystal structure, and additional testing is necessary to determine site assignments.

The possibility of a calcium end member in the turquoise group has been considered since “coeruleolactite” was initially described in 1871 (Peterson, 1871). Note that sample TQ-C1 had significant concentrations of calcium. It is likely, though, that this represents a mixture of turquoise and another mineral in the analysis. Crandallite, a calcium aluminum phosphate mineral—CaAl3(PO4)(PO3OH)(OH)6—was identified from XRD patterns of the matrix material found at the mine. A mixture of crandallite and turquoise in the ablated spot could provide the elevated calcium concentrations that were observed. The heterogeneity of the turquoise itself and the matrix is a problem for accurate chemical analysis and reproducibility, by LA-ICP-MS or wet chemistry bulk composition mass spectrometry.

Importance in the Trade. The color, hardness, and location of Mona Lisa turquoise contribute to its economic value. The color variations within the material are likely caused by alteration and the presence of iron. Mona Lisa turquoise varies significantly in hardness, with some samples able to be cut and polished without stabilization. The physical properties of the mined material are likely dependent on both the mineralization conditions and exposure to weathering.

The matrix pattern of Mona Lisa turquoise is also a distinguishing characteristic. In cut and polished stones, the matrix appears light tan, with some patches of white and brown, such as in the beads shown in figure 20. Mona Lisa turquoise generally lacks the distinctive spiderweb pattern that can add value to certain samples, but the nondescript appearance of the Mona Lisa matrix promotes focus on the turquoise color itself. Localized sulfide mineralization does occur in the Ouachita Mountains, but sulfides were not observed at the Mona Lisa mine or within the matrix material.

The provenance of a colored gemstone can impact its value in the trade. Specific turquoise mines in the American Southwest, Iran, and China produce material of higher market value due to rarity and name recognition. Origin determination of turquoise samples is complicated by multiple factors: the heterogeneity of the material at each site, turquoise’s cryptocrystalline nature, and the sheer number of turquoise-producing mines, many of which are now defunct (and thus difficult to acquire reliable material from). An extensive collection of turquoise from numerous important turquoise-producing regions and mines would need to be analyzed prior to making origin conclusions for an unknown stone.

The Mona Lisa mine’s location increases the rarity and value of the material, because turquoise from Arkansas has been previously unconfirmed or passed off as economically insignificant. However, the value of Mona Lisa turquoise will depend heavily on increased marketing, as the site remains relatively unknown. Until the Mona Lisa mine becomes a known and respected locality for turquoise collectors and dealers, the demand for and subsequent worth of this material will remain lower than that from well-known sources, despite its rarity and peculiarity. Mona Lisa turquoise specimens with the highest value per carat are those hard enough to be cut and polished directly from the mine, which, like with most turquoise mines, is only a small fraction of the material.

CONCLUSIONS

The Mona Lisa mine is a unique turquoise occurrence because of its location in Arkansas—a lesser-known locale. Gemological evaluation, X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and elemental concentrations confirmed that the material is within the turquoise mineral group and has a significant copper component—and thus can be classified as turquoise. The zinc, copper, and iron concentrations also established that the turquoise-group members faustite, planerite, and chalcosiderite potentially can also be found at this location. At the Mona Lisa mine, turquoise mineralized along the ridge of Little Porter Mountain within near-vertical conjugate fractures in weathered novaculite, adjacent to a geologic contact with the Missouri Mountain Shale. The question of how turquoise formed at the site remains: aluminum and phosphorus were likely derived from deep-water shale units (including the Missouri Mountain Shale), while copper mineralization has been described in adjacent areas, often associated with manganese mineralization (Stone and Bush, 1984). In Polk County, manganese deposits are found in the Arkansas Novaculite, with chemical analysis indicating up to 1.40 wt.% copper in manganese-rich samples (Ericksen et al., 1983). With mineralizing fluids traveling along geologic contacts and fractures, the weathering of the shales and manganese ores could have provided the components for turquoise mineralization at the Mona Lisa mine.

At the site, turquoise is mined from a 90-meter-long open trench that deepens toward the center. Compared with many well-known mines in the American Southwest, where turquoise is found associated with economically viable copper deposits, the Mona Lisa mine is a small-scale surface mining operation. At the time of this writing, the site is not operating commercially, but new mineralizations are being uncovered. With the discovery of a copper source in the area, the potential for additional deposits of turquoise would increase. Because the gemological value of turquoise often depends on mine name recognition, historical significance, and rarity, increased public awareness of Mona Lisa turquoise may one day be associated with its increasing value, as it represents a renewed, distinctive source of American turquoise.

.jpg)