Converge 2025 Speaker Presentations

Converge took place at the Omni La Costa Resort in Carlsbad, California, on September 7–10, 2025. This new event united GIA’s gemological research and industry-leading education with the American Gem Society’s (AGS) professional development and networking opportunities.

GIA’s research sessions featured 24 speaker presentations and more than 30 posters, covering broad topics, including colored stones and pearls, diamond identification, diamond and mineral geology, diamond cut, gem characterization, gemology and jewelry, and new technologies and techniques. GIA also offered a number of hands-on sessions including differentiating between natural and laboratory-grown diamonds, an introduction to jewelry forensics, and the photomicrography of gems.

COLORED STONES AND PEARLS

Colored Stone Treatments in the Twenty-First Century: A Review and Current State of Research

Dr. Aaron Palke (GIA, Carlsbad) observed that a major focus of gemological research is always to improve a laboratory’s ability to detect gems accurately and efficiently that are artificially treated to enhance their appearance. As our knowledge grows, laboratories focus on treatments that are increasingly difficult to detect, such as low-temperature heat treatment, chromophore diffusion, and artificial irradiation. Dr. Palke’s talk provided a review of the innovative research on colored stone treatment identification in the twenty-first century. He noted that treatments are not inherently bad, but rather are crucial for miners and the industry because most gems need treatment to be marketable. Similarly, treatments do not decrease value because gemstones that require enhancement typically have little worth otherwise. He quipped, “Big, clean, untreated gems make you rich…treated gems pay the bills!”

Dr. Palke noted that gem enhancement is not new; ancient treatments included dyeing and quench crackling, foil backs, boiling amber in oil, and low-temperature heat treatment of sapphire. By the twentieth century, treaters employed sophisticated furnaces with precise temperature and atmosphere control, radiation, and advanced clarity enhancements such as resins and epoxies for emerald and flux and glass fillings for ruby. Gem treatment in the twenty-first century centered on modifications to established treatments, “new recipes,” and extending existing enhancements to different types of gems, including lattice diffusion, low-temperature heat treatment, irradiation of pink sapphire, and clarity enhancement for non-emerald gemstones. Although lattice diffusion is not a new treatment—titanium-diffused sapphire appeared in the 1970s to ’80s—treaters experimented with introducing other chromophores into gems at high temperatures. Gemological laboratories saw an unusual influx of padparadscha-colored sapphires in the early 2000s and quickly determined their color was due to beryllium diffusion (figure 1). Gem labs also encountered lattice-diffused spinel (first treated with cobalt then nickel) and copper-diffused feldspar. Early production beryllium-diffused sapphire and ruby usually had a thin diffusion rim as beryllium did not diffuse too far into the stone, but treaters soon found the right techniques to diffuse beryllium all the way through. Beryllium treatment usually adds orange, but can also take away blue color. Inclusions in treated stones are often heavily altered, but in general, this is associated with high-temperature heated sapphires.

REFERENCES |

|

Emmett J.L., Scarratt K., McClure S.F., Moses T., Douthit T.R., Hughes R., Novak S., Shigley J.E., Wang W., Bordelon O., Kane R.E. (2003) Beryllium diffusion of ruby and sapphire. G&G, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 84–135, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.39.2.84 Jollands M., Ludlam A., Palke A.C., Vertriest W., Jin S., Cevallos P., Arden S., Myagkaya E., D’Haenens-Johannson U., Weeramongkhonlert V., Sun Z. (2023) Color modification of spinel by nickel diffusion: A new treatment. G&G, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 164–181, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.59.2.164 Kane R.E, Kammerling R.C., Koivula J.I., Shigley J.E., Fritsch E. (1990) The identification of blue diffusion-treated sapphires. G&G, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 115–133. Rossman G.R. (2011) The Chinese red feldspar controversy: Chronology of research through July 2009. G&G, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 16–30, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.47.1.16 |

Field Gemology: A Foundation to Better Understand Gemstones

Wim Vertriest (GIA, Bangkok) presented the exciting topic of field gemology. For more than 15 years, GIA has visited mining locales around the globe to collect gems for scientific research (figure 2). Collecting samples with a high reliability of stated provenance and treatments is critical for any research institution, since the quality of scientific data is directly related to the quality of the samples. Vertriest quoted famed naturalist Sir David Attenborough to illustrate that the research library associated with collections is almost of greater importance than the objects themselves. Important information also comes from the circumstances of documentation that should accompany every scientifically collected specimen. GIA’s colored stone reference collection is well-documented in terms of origin (provenance) and treatment status. It presently contains 30,165 samples—primarily ruby, sapphire, emerald, and spinel, but also other gems including opal and garnet.

Vertriest posed the question of why jewelers, cutters, hobbyists, clients, wholesalers, and retailers should care that GIA invests in field gemology. To answer this question, he introduced the “four pillars” of field gemology, starting with the first: understanding the gems. This means characterizing the gems in terms of their identification, inclusions, chemistry, extent or absence of treatment, and often their geographic origin, if possible. As an aside, Vertriest noted that there are no bad treatments, only bad disclosure. The second pillar is understanding the earth. This means assimilating the environmental and health impacts of mining gems and the working conditions of the miners, as well as deciphering the geological processes at work and why gems are found where they are.

The third pillar is understanding how people trade gems. Who works with the stones, how do they move through the supply chain, where is the value added, and which skills add to those values? Vertriest cited Mozambique’s Winza ruby deposit as an example. Connoisseurs regard its top-quality rubies as the world’s finest, but apart from this tiny percentage, the rest are unusable without treatment. That Mozambique rubies react so well to treatment is one of the key reasons for the success of this material: “B-grade” goods can be made attractive and sellable. If there is no market for low-grade gems, mining will stop and the highest value material will not be found. In other words, treatment is one way to “upgrade” lower-quality material; it allows us to get more value out of the full mine run by producing a range of gems at different price points, which keeps the gem supply chain alive. The fourth pillar is understanding the source. This refers to the context of where the gemstones come from and the people who work with them, along with the meaning these specific gems hold for those who handle and make their livelihoods from them. Vertriest noted that the trade places a lot of value on the origin of certain gemstones without knowing what that means. If you try to understand the source, what makes a certain place so special in terms of its people, culture, and politics becomes clear, because these factors often dictate supply to the trade.

Field gemology allows gemologists to understand the intricacies, dynamics, and complexities that are related to gemstones. Forming a holistic view of a gem and what it represents is critical for any modern gemologist wanting to address the gem industry’s current challenges.

REFERENCES |

|

Hsu T., Lucas A., Pardieu V. (2015) Splendor in the Outback: A visit to Australia’s opal fields. G&G, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 418–427, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.51.4.418 Hsu T., Lucas A., Kane R.E., McClure S.F., Renfro N.D. (2017) Big Sky country sapphire: Visiting Montana’s alluvial deposits. G&G, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 215–227, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.53.2.215 Vertriest W., Girma D., Wongrawang P., Atikarnsakul U., Schumacher K. (2019) Land of origins: A gemological expedition to Ethiopia. G&G, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 72–88, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.55.1.72 Vertriest W., Palke A.C., Renfro N.D. (2019) Field gemology: Building a research collection and understanding the development of gem deposits. G&G, Vol. 55, No. 4, pp. 490–511, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.55.4.490 |

The Value of Pearl Impact

Pierre Fallourd (Onegemme, Perth, Western Australia) addressed the origin and societal and environmental impact of cultured pearls, rather than the physical attributes, that contribute to their perceived worth. The presentation focused on the mission to measure, manage, and share the value of pearls’ social and environmental impact. Fallourd noted that origin and impact are emerging as equally important factors throughout the jewelry value chain; pearl is the one gem that exemplifies the need for humans and nature to coexist in harmony.

Traditionally, pearls are valued based on their appearance using GIA’s 7 Pearl Value Factors: size, shape, color, luster, surface, nacre, and matching. Fallourd posed the concept of pearl as the first “nature positive” gem, adding that the pearl farming-to-retail supply chain has the potential to make a positive impact on climate change, water quality, biodiversity, habitat, and society. Fallourd identified how a well-run, ecologically conscious cultured pearl farm might offset climate change and improve water quality and marine habitat. Both pearls and oyster shells capture carbon and produce mother-of-pearl, which is a widely used, long-lasting decorative product. Oysters extract nutrients, in the form of nitrogen and phosphorus, and heavy metals to improve water quality. One metric ton of farmed oysters can remove 10 kg of nitrogen, 0.5 kg of phosphorus, and 0.7 kg of heavy metals. A farm of 40,000 oysters turns over >2,000,000 liters (nearly one Olympic-sized swimming pool) every hour. Pearl oysters house diverse and abundant epifauna that adds to the ecosystem; a 1-hectare farm might produce more than one extra metric ton of catchable fish by providing additional spawning habitats.

Pearling and pearl farming are labor-intensive and create direct skilled employment often in remote locations. Communities also benefit through fair trade, creation of wealth, and transfer of knowledge. However, there are risks to be mitigated; badly run farms can produce excess sewage, increase sediment, and encourage overfishing, invasive species, and disease, while emissions reduction and use of renewable energy might be costly. The social and environmental benefits of marine pearl farming vary according to species, processes, and location. Every opportunity comes with an attached risk that should be monitored and moderated. The benefits can exceed the cost to the communities and ecosystems for each hectare farmed. Their value can be measured and managed, and pearl farming can deliver value throughout the entire pearl supply chain, leading to a virtuous cycle. If provenance and best practices can be demonstrated, retailers have additional storytelling resources to engage and enthuse consumers.

REFERENCE |

|

Alleway H. (2023) Gem News International: An environmental, social, and governance assessment of marine pearl farming. G&G, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 404–406. |

Pearl Testing and Research at GIA: A Brief History and Recent Updates

In this presentation, Dr. Chunhui Zhou (GIA, New York) provided a brief history of GIA’s advances in pearl testing technology and research, which have helped GIA solve various identification challenges for this unique and timeless biogenic gem. Dr. Zhou traced GIA’s pearl testing legacy back to the 1930s, when Japanese akoya cultured pearls were first successfully commercialized, and the ability to separate natural pearls from their cultured counterparts presented gemological laboratories with a major identification challenge. In the 1930s, GIA used the endoscope, an optical device that revealed the presence of a bead nucleus under the nacre of a cultured pearl. In the 1940s, GIA elaborated this device into the Pearloscope, which also detected the shell-banding structure in the beads. By the 1950s, X-ray equipment was obligatory for pearl identification, and pearl testing amounted to more than 90% of the GIA Gem Testing Laboratory’s business. Dr. Zhou emphasized that the importance of pearls to the industry has continued to drive four primary areas of pearl-related research at GIA: a pearl’s natural or cultured nature (figure 3), whether it was produced in a saltwater or freshwater environment, the type of mollusk that produced it, and whether the mollusk produces nacreous, porcelaneous, or non-nacreous pearls. A fifth consideration, if present, is the degree and type of treatment. Dr. Zhou highlighted the various research publications GIA scientists have contributed over the years, many of which are listed below.

REFERENCES |

|

Homkrajae A., Manustrong A., Nilpetploy N., Sturman N., Lawanwong K., Kessrapong P. (2021) Internal structures of known Pinctada maxima pearls: Natural pearls from wild marine mollusks. G&G, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 2–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.57.1.2 Nilpetploy N., Lawanwong K., Kessrapong P. (2018) Non-bead cultured pearls from Pinctada margaritifera. GIA Research News, April 27, https://www.gia.edu/ongoing-research/non-bead-cultured-pearls-from-pinctada-margaritifera Scarratt K., Sturman N., Tawfeeq A., Bracher P., Bracher M., Homkrajae A., Manustrong A., Somsa-ard N., Zhou C. (2017) Atypical “beading” in the production of cultured pearls from Australian Pinctada maxima. GIA Research News, February 13, https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/atypical-beading-production-cultured-pearls-australian-pinctada-maxima Sturman N., Homkrajae A., Manustrong A., Somsa-ard N. (2014) Observations on pearls reportedly from the Pinnidae family (pen pearls). G&G, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 202–215, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.50.3.202 Sturman N., Bergman J., Poli J., Homkrajae A., Manustrong A., Somsa-ard N. (2016) Bead-cultured and non-bead-cultured pearls from Lombok, Indonesia. G&G, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 288–297, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.52.3.288 |

An Overview of the Natural Gulf Pearl Trade

Abeer Al-Alawi (GIA, Mumbai) provided an overview of the natural pearl trade in the Persian (Arabian) Gulf. Historically, this area—particularly Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—was considered the center of the natural pearl trade. Pearl diving was an essential livelihood of many communities in the Gulf, which were renowned for producing some of the world’s finest natural pearls, known among Indian traders as “Basra pearls,” a term that remains in use to this day. Traders transported Persian Gulf pearls from the port town of Basra in southern Iraq by sea on dhows and other vessels to India, where they were processed, sorted, drilled, and strung before being sold in Europe and other markets worldwide.

The period between 1850 and 1930 marked the peak of natural pearl fishing in the Persian Gulf, when the area supplied perhaps 70–80% of the world’s natural pearls. During this time, Bahrain was the epicenter of the natural pearl trade. Al-Alawi noted that Bahrain had the richest pearling beds followed by Kuwait and Qatar. Two important sites are considered the “home of pearling” in the UAE: Dubai and Abu Dhabi. Julfar, now known as Ras Al Khaimah in the UAE, was one of the most important pearling centers and was recognized for producing the best quality pearls due to its location between the main pearl banks and Hormuz. The pearling beds were typically at depths between 6 and 20 meters, with deeper areas reaching up to 30 meters. Traditionally, the diving season was from April to September. Divers remained under water for 60 to 90 seconds using a nose clip. Larger pearling ships required a crew of 60 to 80, including a captain, captain’s assistant and crew head, singer (one of the most important roles), diver, trainee, puller, and cook. At the end of the season, shares would be distributed by function; the diver would take two shares and the puller only one, while the singer would take two shares for his distinguished role on board.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most Gulf pearls were shipped to and processed in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, which has been a significant pearl manufacturing, processing, and trading hub for centuries. To showcase the high-quality Basra pearls, Bombay traders would sort the pearls, string them with silk threads, and tie them together at both ends using decorative metallic cords of various colors. These bunches were in great demand in Europe’s pearl markets and were sold as “Bombay bunches.” By the mid-1930s, three factors caused natural pearl revenues to plunge more than 70%: the economic impact of the Great Depression, the discovery of oil in the Persian Gulf, and the advent of commercial quantities of Japanese akoya cultured pearls. However, Al-Alawi highlighted the present-day resurgence of interest in natural pearls driven by a growing appreciation for their rarity and unique history (figure 4).

REFERENCES |

|

Hohenthal T.J. (1938) The Bombay pearl market—Summary of a report. G&G, Vol. 2, No. 9, pp. 159–160. Kennedy L., Homkrajae A. (2023) Gem News International: Spotlight on natural nacreous pearls. G&G, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 112–113. Lesh C. (1980) Born in the depths: The perfect pearl. G&G, Vol. 16, No. 11, pp. 356–365. |

An Overview and Update on the GIA 7 Pearl Value Factors Classification System

Cheryl (Ying Wai) Au (GIA, Hong Kong) opened by posing the question of how we should describe the beauty or the quality of pearls in language that everyone can understand. Similar to the Four Cs for diamonds, GIA developed the GIA 7 Pearl Value Factors. This system offers consistency and provides customers with the knowledge needed to make an informed purchase. We can apply it to all nacreous pearls, including the four major cultured pearl types in the market: akoya, South Sea, Tahitian, and freshwater (figure 5). Au summarized GIA’s long history with pearls. The Institute began offering pearl identification services in 1949, a few years before the introduction of diamond grading. Gems & Gemology published the first paper discussing pearl value factors and classification in 1942, though it focused on natural pearls. In 1967, the GIA 7 Pearl Value Factors were first identified and described by Richard T. Liddicoat Jr. with an emphasis on cultured pearls. Today, a GIA Pearl Identification Report provides extensive information including pearl quantity, weight, size, shape, color, overtone, natural or cultured identity, mollusk type, saltwater or freshwater environment, and any detectable treatments.

In 2021, GIA launched a Cultured Pearl Classification Report that clearly states the 7 Pearl Value Factors of the submitted pearl items. Au covered recent updates to some terms adopted by GIA including the recently expanded nacre quality scale, and defined each value factor:

- Size is determined by weighing and measuring the pearl. Pearl size is expressed in millimeters and pearl weight in carats (typically), both to two decimal places. Different pearl types have different size ranges. For example, akoya pearls are generally smaller with a typical size range of 6–9 mm, and South Sea pearls might range from 13–20 mm.

- GIA classifies pearls into seven main shapes: round, near-round, drop, oval, button, semi-baroque, and baroque.

- Pearl colors have three different components: bodycolor, overtone, and orient. Bodycolor combines hue, tone, and saturation. GIA uses 19 hue names for pearls. Tone is the relative lightness or darkness of a color, ranging from white, through various shades of gray, to black. Saturation is the relative weakness or strength of color, first neutral, then from very light to strong. Overtone is a single translucent color overlying a pearl’s bodycolor, while orient is any combination of multiple overtone colors or iridescence overlying a pearl’s color.

- Luster describes the intensity and sharpness of reflections seen on a pearl’s surface. After comparison with specific pearl luster masters, GIA classifies a pearl’s luster grade as Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, or Poor. Different pearl types have varying inherent luster ranges, so an Excellent luster for one type might only be Very Good for another.

- Surface classification describes the degree of spotting on a pearl’s surface, and also considers the number, severity, and positioning of visible blemishes. After comparing to pearl surface masters and judging the surface condition, a pearl’s surface is classified into one of four categories: clean, lightly spotted, moderately spotted, and heavily spotted.

- Nacre grades are based on three elements: thickness, continuity, and condition. GIA’s nacre grade reflects the condition of a pearl’s nacre, which affects luster, surface, and sometimes durability. The pearl’s nacre layer should meet required minimum thickness standards for each pearl type: for akoya this is at least 0.15 mm, for Tahitian at least 0.80 mm, and for South Sea at least 1.50 mm. Pearls with thin nacre show a chalky appearance and the beads are readily visible under strong lighting. Nacre continuity is the lack of disruptions or “movement” in nacre layering, or in other words, the smoothness and “cleanliness” of the pearl. Nacre condition includes any post-harvest considerations, such as processing, polishing, and working, as well as wear and damage.

- Matching is defined as the uniformity of appearance in strands and multiple pearl groups or items. Well-matched, high-quality pearl sets show uniformity of color and shape, while lower-quality sets display greater variation in shape and color.

REFERENCES |

|

Ho J.W.Y., Shih S.C. (2021) Pearl classification: The GIA 7 Pearl Value Factors. G&G, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 135–137, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.57.2.135 Liddicoat R.T. Jr. (1967) Cultured-pearl farming and marketing. G&G, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 162–172. Rietz P.C. (1942) The classification and sales possibilities of genuine pearls. G&G, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 9–12. ——— (1942) The classification and sales possibilities of genuine pearls. G&G, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 25–28. |

DIAMOND IDENTIFICATION

Distinguishing Diamonds: Understanding the Differences Between Natural and Laboratory-Grown Diamond Formation and Their Unique Stories

Dr. Ulrika D’Haenens-Johansson (GIA, New York) outlined the momentous transformation in the diamond industry over the past 20 years due to the advent of commercial laboratory-grown diamonds (LGDs), discussing the differences in natural and LGD formation and highlighting the resulting clues that they provide, which allow conclusive separation (figure 6). Production of LGDs has surged significantly with pronounced improvements in their size and quality; forecasted 2025 production is approximately 30 million carats of LGD gem rough. Despite sharing key crystal properties with natural diamonds, LGDs have fundamentally distinct formation mechanisms and stories from diamonds that formed millions to billions of years ago deep within the earth.

Dr. D’Haenens-Johansson noted that LGDs are widely available and have garnered a lot of press coverage, resulting in a mixture of both highly informed and misinformed clients and retailers, which creates considerable confusion and mistrust. “Bad actors” can intentionally mix LGDs with natural diamonds, or it might happen inadvertently. Dr. D’Haenens-Johansson stressed that clear differentiation of both products is key.

Natural diamonds are old, having formed 90 million to 3.5 billion years ago. For comparison, the extinction of dinosaurs happened 65 million years ago, and the age of Earth is 4.56 billion years. Natural diamonds form within the earth from carbon-containing fluids and rocks at greater depths than any other gemstone. Most derive from rocks 150–200 km below the earth’s surface, but some originate deeper: 700 km. They are brought up to the surface by ancient volcanic eruptions in kimberlite pipes. Natural diamonds are rare; it takes roughly 100,000 metric tons of ore to find a single one-carat D-color flawless diamond (a grade of >0.01 carat/metric ton).

LGDs are mass-produced in factories. Their composition and crystal structure are the same as natural diamond, with essentially the same physical, chemical, and optical properties. They can be differentiated because they have a fundamentally different origin from natural diamonds. LGDs are produced by two main methods: high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT), accounting for 20% of production, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) representing 80%. HPHT synthesis uses a press that mimics the conditions of natural diamond growth, but not the chemistry. LGD growth occurs at pressures of 5–6 GPa and temperatures of 1300–1600ºC over durations of days to months. CVD synthesis uses a gaseous carbon source with hydrogen, diamond seed plates, microwaves to activate plasma and low pressures (one twentieth to one quarter atmospheres) and temperatures of 700–1200ºC to build up LGDs layer-by-layer over a period of days to months.

GIA has been researching synthetic diamonds since their inception. Robert Crowningshield was the first gemologist to inspect General Electric’s gem-quality specimens in the 1970s. GIA continues to analyze LGDs from the trade and also conduct in-house synthesis of CVD LGDs. GIA has developed a fundamental understanding of the material and its evolution over time and can recognize the difference between natural diamonds and LGDs. Humans cannot reproduce natural diamond formation and residence conditions, so natural diamonds and LGDs are not identical. They each contain clues of their origin that allow us to clearly separate them using laboratory services and screening equipment.

REFERENCES |

|

Ardon T., McElhenny G. (2019) Lab Notes: CVD layer grown on natural diamond. G&G, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 97–99. Eaton-Magaña S., Breeding C.M. (2018) Features of synthetic diamonds. G&G, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 202–204, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.54.2.202 Eaton-Magaña S., Shigley J.E. (2016) Observations on CVD-grown synthetic diamonds: A review. G&G, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 222–245, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.52.3.222 Eaton-Magaña S., Shigley J.E., Breeding C.M. (2017) Observations on HPHT-grown synthetic diamonds: A review. G&G, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 262–284, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.53.3.262 Eaton-Magaña S., Hardman M.F., Odake S. (2024) Laboratory-grown diamonds: An update on identification and products evaluated at GIA. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 146–167, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.2.146 Wang W., Persaud S., Myagkaya E. (2022) Lab Notes: New record size for CVD laboratory-grown diamond. G&G, Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 54–56. |

Screening and Detection of Synthetic Diamonds

Dr. David Fisher (De Beers, Maidenhead, United Kingdom) acknowledged that laboratory-grown diamonds (LGDs) are now an established part of the jewelry trade and gave a brief history of diamond synthesis from the 1950s, citing the many advances in quality and size that have made LGDs a commercial commodity in today’s markets. The talk outlined the approaches taken to date to address the challenge along with the developments that have allowed the application of screening technology to the wide range of sizes affected by LGD production. Dr. Fisher emphasized the need to extend screening capability beyond the laboratory and into retail, where the ability to clearly demonstrate a diamond’s natural origin could assist retailers in the promotion of natural diamonds.

The presentation outlined the many options for diamond verification instruments (DVIs) available to the trade. Some of the screening methods these devices use include absorption, fluorescence, or phosphorescence, often relying on the N3 defect (a vacancy surrounded by three nitrogen atoms, which appears in the vast majority of natural diamonds, but is absent in LGDs and diamond simulants). Dr. Fisher also described the pressures the trade exerts on manufacturers of DVIs, including cost, compact size, accuracy of screening, and volume, especially where melee-size diamonds are concerned. The Natural Diamond Council’s (NDC) Assure Program verifies the performance of commercially available DVIs used to separate natural diamonds and LGDs. All instruments are rigorously tested by an independent third-party laboratory using a standard methodology and various sample sizes of natural diamonds, LGDs, and diamond simulants. Key metrics include false-positive rate (wrongly identifying a synthetic diamond as natural) and the referral rate (correctly identifying a stone that needs further testing). NDC publishes results online, which are available to anyone in the diamond trade. Dr. Fisher noted that the optimal false-positive rate is 0%; it is “really bad” if any LGDs are passed as natural. Of the 32 DVIs tested in the first iteration of the Assure Program (2019), only 14 (32%) gave a 0% false-positive rate. By Assure 2.0 (2025), the false-positive rate was much better: 15 out of 18 (83%) returned a zero false-positive rate.

REFERENCES |

|

Crowningshield R. (1971) General Electric’s cuttable synthetic diamonds. G&G, Vol. 13, No. 10, pp. 302–314. De Beers Diamond Verification Instruments: https://verification.debeersgroup.com/diamond-verification-instruments/ Eaton-Magaña S., D’Haenens-Johansson U.F.S. (2012) Overview and Update: Recent advances in CVD synthetic diamond quality. G&G, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 124–127. Eaton-Magaña S., Shigley J.E. (2016) Observations on CVD-grown synthetic diamonds: A review. G&G, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 222–245, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.52.3.222 Fisher D. (2018) Addressing the challenges of detecting synthetic diamonds. G&G, Vol. 54, No. 3, pp. 263–264. Natural Diamond Council ASSURE Program: https://www.naturaldiamonds.com/council/assure-testing-program/ Shigley J.E., Fritsch E., Stockton C.M., Koivula J.I., Fryer C.W., Kane R.E. (1986) The gemological properties of the Sumitomo gem-quality synthetic yellow diamonds. G&G, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 192–208. Shigley J.E., Fritsch E., Stockton C.M., Koivula J.I., Fryer C.W., Kane R.E., Hargett D.R., Welch C.W. (1987) The gemological properties of the De Beers gem-quality synthetic diamonds. G&G, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 187–206. Shigley J.E., Fritsch E., Koivula J.I., Sobolev N.V., Malinovsky I.Y., Pal’yanov Y.N. (1993) The gemological properties of Russian gem-quality synthetic yellow diamonds. G&G, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 228–248. Wang W., Hall M.S., Moe K.S., Tower J., Moses T.M. (2007) Latest-generation CVD-grown synthetic diamonds from Apollo Diamond Inc. G&G, Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 294–312. Wang W., D’Haenens-Johansson U.F.S., Johnson P., Moe K.S., Emerson E., Newton M.E., Moses T.M. (2012) CVD synthetic diamonds from Gemesis Corp. G&G, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 80–97, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.48.2.80 |

DIAMOND AND MINERAL GEOLOGY

Determining a Diamond’s Country of Origin: Dream or Reality?

Dr. Michael Jollands (GIA, New York) questioned whether gemological laboratories might develop methods to determine a diamond’s country of origin just as many have for colored gems such as sapphire, ruby, and emerald, which are generally submitted without any documentation. In this talk, Dr. Jollands discussed the challenges of determining a diamond’s country of origin, the pitfalls of some proposed methods, and future opportunities for tracing a diamond’s mine-to-market path. Most colored stones form up to a few tens of kilometers below the earth’s surface, where there can be major geologic differences from place to place. In contrast, diamonds form much deeper in the lower lithosphere or mantle, hundreds of kilometers below the surface. Here, there are only minor differences between different parts of the earth.

For colored gems, laboratories use several methods for determining origin: inclusions or visual observations, trace element chemistry (energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence or laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry), and spectroscopy. Trace elements exist in gems in very small amounts at the parts-per-billion (ppb) or parts-per-million (ppm) level and are not normally part of the crystal. Some well-known trace elements in diamond are nitrogen, hydrogen, boron, silicon, oxygen, and nickel. Many other elements can exist in fluid inclusions inside diamonds. These inclusions may be visible or invisible, and unevenly distributed, and the elements they contain are generally present at the parts-per-million to parts-per-trillion levels. Analysis is extremely challenging and destructive, even with new, highly sensitive equipment.

Published work and GIA’s own testing show complete overlap between the trace element chemistry of diamonds from different locations. Some differences do exist, but these are associated with different diamond-forming fluids, which are not geographically specific. In contrast, colored stones often show very clear separation between samples from different geographic origins. For example, copper-bearing tourmaline from different locales can be separated using gallium, lead, copper, strontium, and zinc levels. To the best of current knowledge within GIA and the academic community, no similar separation exists for diamonds. Gemologists routinely use three kinds of spectroscopy: infrared (IR), ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR), and photoluminescence (PL). Only IR spectroscopy shows promise. One set of defects associated with nitrogen and hydrogen may be useful because their spectra can be used to determine how long the diamond sat in the earth at a given temperature. Diamonds from different locations have different time and temperature histories. Although a current global dataset of around one million stones shows some correlation, samples from the same location can fall across the whole plot, with overlap between diamond ages from different locations.

Dr. Jollands concluded that many diamonds lack visible inclusions, trace elements are very challenging to measure, and characteristics completely overlap between sources. Spectroscopy offers no geographical separation, and tracing stones from source to consumer appears to be the only viable method for tracking diamond origin today (figure 7). This brings many challenges, including tagging stones at every step and stopping inadvertent or deliberate swapping of stones, but these can be overcome, whereas geologic limitations cannot.

REFERENCE |

|

Smith E.M., Smit K.V., Shirey S.B. (2022) Methods and challenges of establishing the geographic origin of diamonds. G&G, Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 270–288, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.58.3.270 |

Lithospheric Diamonds and Their Mineral Inclusions: A Glimpse into the Ancient Earth’s Mantle

Dr. Mei Yan Lai (GIA, Carlsbad) began by explaining how kimberlite and lamproite eruptions sample Earth’s mantle to bring diamonds to the surface. The extreme hardness and chemical inertness of diamond enable it to serve as a probe into the composition of Earth’s mantle and as a recorder of geotectonic history spanning millions to billions of years. Approximately 99% of recovered diamonds form in the subcratonic lithospheric mantle at depths of 140–200 km. While these depths cannot be directly sampled by any physical method, mantle rocks and occasionally diamond have erupted to the surface by deep-seated kimberlite volcanism.

The two mantle rocks for lithospheric diamond formation are peridotite (primarily made of olivine, enstatite, and chrome diopside, along with accessory minerals such as spinel, garnet, and sulfides) and eclogite (mostly garnet and omphacite with accessory minerals such as kyanite, coesite, rutile, corundum, and sulfides). Diamonds can be monocrystalline, fibrous, or polycrystalline. Monocrystalline diamonds typically display octahedral shapes, but can be cubic, twinned (e.g., macles), or irregular in shape. Diamond crystals can also undergo dissolution, transitioning from octahedral to dodecahedral forms, depending on the extent of resorption. Surface features including trigons or tetragons, hillocks, deformation lines, or hexagons are signs of dissolution and may be preserved on the girdles of polished diamonds. Mineral inclusions in diamond are signatures of the mantle rocks they grew in and can be identified by Raman spectroscopy. Characteristic inclusions of peridotitic diamonds are purple garnet, bright green chrome diopside, colorless enstatite, olivine, and dark red chromite. Eclogitic diamonds might contain orange garnets (figure 8), grayish green omphacites, colorless coesite, brownish orange rutile, or blue kyanite.

Dr. Lai explained the circumstances under which scientists employ a technique called chemical geothermobarometry to estimate the pressure and temperature conditions of the mantle. They analyze the chemical composition of pairs of coexisting mineral inclusions such as garnet and olivine in peridotitic diamonds or garnet and omphacite in eclogitic ones. Iron and magnesium partition themselves between these minerals in a way that is highly dependent on temperature. After measuring each mineral’s iron-magnesium ratio, scientists use experimentally derived equations to calculate the formation temperature.

The eruption ages of diamond-bearing kimberlites and lamproites range from around 20 million to 1 billion years. Scientists use radioactive decay systems to infer diamond age. Unfortunately, the half-life of carbon-14 is too short and cannot be used for objects older than 57,000 years. Radioactive decay systems with longer half-lives are used instead (41 billion years for rhenium-osmium in sulfide minerals and 106 billion years for samarium-neodymium in garnets and clinopyroxene). Dr. Lai concluded by placing natural diamonds in context with Earth’s 4.56-billion-year timeline. Peridotitic diamonds from Canada’s Ekati mine (3.5 billion years old) and eclogitic ones from Botswana’s Jwaneng mine (2.9 billion years old) bracket the onset of plate tectonics (about 3 billion years ago). Dr. Lai noted that natural diamonds are among the oldest and most remarkable objects to wear and long predate the extinction of the dinosaurs (65 million years ago) and the advent of our own species, Homo sapiens, a mere 300,000 years ago.

REFERENCES |

|

Hardman M.F., Lai M.Y. (2023) Gem News International: Diamondiferous mantle eclogite: Diamond surface features reveal a multistage geologic history. G&G, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 402–404. Kirkley M.B., Gurney J.J., Levinson A.A. (1991) Age, origin, and emplacement of diamonds: Scientific advances in the last decade G&G, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 2–25, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.27.1.2 Shirey S.B., Shigley J.E. (2013) Recent advances in understanding the geology of diamonds. G&G, Vol. 49, No. 4, pp. 188–222, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.49.4.188 |

Superdeep Diamonds: Exceptional Gems with an Incredible Backstory

Dr. Evan Smith (GIA, New York) described research led by GIA in the past decade revealing that many high-quality type II gem diamonds, known for their purity, come from unusually extreme depths inside the earth. Known as superdeep diamonds, this rare geological category of diamond originates from depths of 300–800 km. All gem diamonds form much deeper in the earth (around 140 to 200 km) than colored gems (only up to a few tens of kilometers), but only some are superdeep. These represent 1–2% of mined diamonds and ascend in low-density rocks to depths of about 200 km, where they might be brought to the surface in kimberlites. The depths these diamonds originated from are determined by their mineral inclusions that represent the pressure and temperature conditions of their formation. Scientists recognized ferropericlase and majoritic garnet in the 1980s and used high-pressure experiments as a basis for comparison to confirm their deep origin in the mantle. These discoveries provide a bigger picture of diamonds; lithospheric diamonds crystallize from carbon-containing fluids at depths of 150 to 200 km, whereas superdeep or sublithospheric diamonds form at depths of 300 to 800 km and subduction of oceanic lithosphere is a key ingredient in their formation. Ringwoodite, a high-pressure version of olivine, is stable at depths of 520 to 660 km in Earth’s mantle, so the discovery of a hydrous ringwoodite inclusion in a superdeep diamond is evidence of subducted water. Unlike most lithospheric diamonds, which contain nitrogen and are therefore type I, superdeep diamonds are type IIa—containing essentially no nitrogen with levels of <5 parts per million (ppm)—or IIb, which contain traces of boron. Type I lithospheric diamonds represent 98% of all gem diamonds, whereas type IIa (1–2%) and IIb (<0.02%) are incredibly rare. Some of the world’s most valuable gems are type IIa superdeep diamonds, including the 530.2 ct Cullinan I diamond set in the Sovereign’s Scepter with Cross, part of the British Crown Jewels.

Scientists use the acronym CLIPPIR to describe these big gems: Cullinan-like, Large, Inclusion-Poor, Pure, Irregular, and Resorbed. The inclusions in CLIPPIR diamonds are associated with deeply subducted oceanic plates. Some of these inclusions are metallic (a mix of iron, nickel, carbon, and sulfur), and molten during diamond growth, representing the diamond-forming medium. Superdeep diamond genesis results from the warming and deformation of altered oceanic lithosphere at depth. Three fluid-generating mechanisms are important to diamond formation: the melting of carbonates, the release of water, and the evolution of a metallic melt. The ideas associated with natural diamond are some of the most unique in all geosciences: they form as a result of large-scale movements of plate tectonics; they are ancient (up to 3.5 billion years old); they are the deepest-derived objects you can touch; and they reach the earth’s surface in strange volcanoes. Diamonds are a window into the hidden processes of the planet’s interior, giving them both a tremendous scientific value and a fascinating natural history.

REFERENCES |

|

Eaton-Magaña S., Breeding C.M., Shigley J.E. (2018) Natural-color blue, gray, and violet diamonds: Allure of the deep. G&G, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 112–131, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.54.2.112 Shirey S.B., Shigley J.E. (2013) Recent advances in understanding the geology of diamonds. G&G, Vol. 49, No. 4, pp. 188–222, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.49.4.188 Smith E.M., Shirey S.B., Nestola F., Bullock E.S., Wang J., Richardson S.H., Wang W. (2016) Large gem diamonds from metallic liquid in Earth’s deep mantle. Science, Vol. 354, No. 6318, pp. 1403–1405, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1303 Smith E.M., Shirey S.B., Wang W. (2017) The very deep origin of the world’s biggest diamonds. G&G, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 388–403, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/gems.53.4.388 |

Gem Mineral Evolution: Gemology in the Context of Deep Time

Dr. Robert M. Hazen (Carnegie Institution Earth and Planets Laboratory, Washington, DC, and George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia) placed gem minerals in the context of mineral evolution. The range and diversity of Earth’s minerals are a consequence of more than 4.5 billion years of new physical, chemical, and ultimately biological processes. The concept of mineral evolution represents a new framing of mineralogy for education and public engagement. It explains the change over time of the diversity of mineral species, their relative abundance, and compositional ranges, along with their grain sizes and shapes. It also explains why smaller bodies in our solar system, such as Mars and our own moon, have less diverse assemblies of minerals. Dr. Hazen noted that mineral evolution focuses exclusively on near-surface mineral phases (<3 km in depth), as these are accessible on Earth and most likely to be observed on other planets and moons.

Ten mineral evolution stages were identified over a period of 4.5 billion years, starting with just 25 mineral species and 16 chemical elements, and leading to >6,000 minerals and 72 essential elements today. Dr. Hazen related each stage to major events in Earth’s history, including the heat and impact of planetary accretion, the transition from a “dry” to a “wet” planet through volcanism and outgassing of water and other volatiles, and the formation of granite and the onset of plate tectonics to oxygenation and the rise of life. At each stage, the range of possible minerals increases, including gems. Peridot appears around 4.55–4.35 billion years ago, as the young planet’s internal heat drove volcanism and outgassing of water. Pegmatite gems such as beryl, spodumene, and tourmaline (figure 9) occur as granite forms through crustal remelting and differentiation around the 3.5-billion-year mark. With the onset of plate tectonics around 3 billion years ago, conditions became suitable for the formation of gem corundum, garnet, and jadeite. With the dawn of life, the rise of photosynthesis, and the production of an oxygen-rich atmosphere between 2.5 and 1.85 billion years ago, gem minerals such as azurite, malachite, and turquoise became possible. At each stage of mineral evolution, the range, diversity, and number of minerals increased. Dr. Hazen explained that each mineral or gem specimen is a treasure trove of information, revealing rich detail about formation processes and times.

Dr. Hazen introduced applications of powerful analytical and visualization methods to the characterization of mineral origins and the prediction of new mineral deposits, noting that we have entered a new age of mineral informatics where multidimensional analysis and visualization of mineral systems are leading to insights into the co-evolution of Earth and life. The talk concluded with a proposal that the diversity and distribution of minerals on Earth is a planetary-scale biosignature.

REFERENCES |

|

Hazen R.M. (2010) Evolution of minerals. Scientific American, Vol. 302, No. 3, pp. 58–65. Hazen R.M., Morrison S.M. (2020) An evolutionary system of mineralogy. Part I: Stellar mineralogy (>13 to 4.6 Ga). American Mineralogist, Vol. 105, No. 5, pp. 627–651, http://dx.doi.org/10.2138/am-2020-7173 Hazen R.M., Papineau D., Bleeker W., Downs R.T., Ferry J.M., McCoy T.J., Sverjensky D.A., Yang H. (2008) Mineral evolution. American Mineralogist, Vol. 93, No. 11-12, pp. 1693–1720, http://dx.doi.org/10.2138/am.2008.2955 |

DIAMOND CUT

Modern Diamond Design

Dr. Jim Conant (GIA, Las Vegas) explored how new computational tools help navigate the vast design space of possible facet arrangements for polished diamonds, enabling both novel cuts and optimization of traditional cuts for light performance. Dr. Conant explained the basics of diamond optical performance and the work behind the creation of some new diamond cuts. The foundation of all diamond cut analysis is the concept of “virtual facet pattern.” This helps interpret and model the various optical phenomena that contribute to or detract from the beauty of a cut diamond. It accounts for attributes such as brightness, light leakage, “crushed ice,” “dark zone” patterns, fire, and scintillation, as well as enabling the creation of new diamond cuts, faceting arrangements, and cut geometries.

Virtual facets are the complex shifting patterns of little polygons that the observer sees, similar to a hall of mirrors, as a moving diamond’s facet geometry reflects light back to the eye. Taking a single virtual facet near the edge of the table of an ideal cut round brilliant as an example, Dr. Conant explained that light striking the inside surface of a diamond at all but the steepest angles reflects off the internal surface like a mirror. As the remaining light enters the gem, it refracts as it passes through the crown, reflects twice off the pavilion, and finally travels out of the stone from the crown back to the observer’s eye. Because this light meets several different facets along the way, it fragments into several columns. From the observer’s perspective, each virtual facet collects light from a different region in the environment.

Dr. Conant explained that a diamond’s appearance is quite sensitive to slight differences in pavilion angle; at 41.4 degrees, the beam path no longer exits the crown but reflects back down to the pavilion where it collects light from underneath the diamond, leading to “partial leakage.” Showing the example of a poorly cut pear-shaped diamond cut to match the shape of the rough and maximize weight, Dr. Conant noted that sometimes leakage is even more obvious when the beam immediately exits through the pavilion without any reflections. The stone’s poor appearance results from a too shallow pavilion, allowing light to leak out the bottom and create a “dark zone.” Leakage detracts from a diamond’s appearance, especially when it creates a big and blocky pattern. This is an example of a virtual facet drawing light from a dark place in the environment.

Next, Dr. Conant touched upon “crushed ice,” the part of some diamond fancy shapes composed of thousands of tiny virtual facets. These tiny virtual facets draw light from a randomized subset of the environment and correspond to differing focal lengths. Rather than distinct, geometric facets with crisp edges and high contrast between light and dark areas, crushed ice features many small, irregular facets that blend light in a shimmering way, like shattered glass. Diamonds with little variation in brightness can appear less appealing than those with some contrasting dark regions. However, some dark features are universally disliked. Classic “bow tie” patterns can be appealing when less severe and more transient. The more persistent a dark zone is across different tilts, viewing distances, and lighting environments, the more likely it is to be perceived as negative.

REFERENCE |

|

Reinitz I.M., Gilbertson A., Blodgett T., Hawkes A., Conant J., Prabhu A. (2024) Observations of oval-, pear-, and marquise-shaped diamonds: Implications for fancy cut grading. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 280–304, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.3.280 |

Toward a Fancy Cut Grade

For Jason Quick (GIA, Las Vegas), diamond cut is more than symmetry and light; it shapes style, taste, and personality. How can GIA help define and teach the design factor? Fancy cuts offer seemingly limitless design possibilities that defy exhaustive exploration (figure 10). However, exploring this vast array of potential fancy-cut designs enables rather than constrains innovation. Quick reflected that both AGS and GIA have a long history of diamond-cut research leading to today’s Project Everest. This collaboration started with high-level meetings in 2020, led to the integration of both research teams in 2022, and to AGS Labs formally becoming GIA’s Diamond Cut R&D Lab in 2023.

GIA’s upcoming fancy cut grading system will use ray tracing on 3D wireframe models to assess light performance and will prioritize diamond beauty over fixed proportion ranges. This system must solve challenges for retailers, and by necessity, be packaged with education that makes the system intuitive to use and explain to consumers. He noted that diamond cut planning involves three stages: (1) mapping of rough, (2) planning, and (3) polishing. Mapping involves 3D plotting of inclusions (size, type, and location) along with color estimation. Planning produces permutations of size and cutting style to maximize yield and quality in terms of the Four Cs. This provides an estimate of potential gem value and marketability (liquidity). Polishing transforms the diamond through sawing, bruting (shaping), blocking, and final polishing into a finished gem.

Recent advances in GIA cut research encompass cut space (mathematical models of all possible faceting arrangements), optics (simulations of light moving through faceted diamonds), and metric development (modeling and quantifying optical phenomena, such as “crushed ice” and “bow ties”). The objective of the system is to produce fancy-cut designs that deliver high performance across the most commonly encountered lighting environments and that maintain superior performance face-up, when tilted, and from various viewing distances. To support manufacturers, GIA is developing Facetware “software as a service” (SaaS), enabling the submission of 3D models for preliminary cut grade assessments to assist diamond designers and manufacturers. This system will provide cut analysis (a provisional cut grade, including symmetry evaluation), plans to support decisions before polishing, and scans to support quality control metrics after polishing.

REFERENCES |

|

Blodgett T., Gilbertson A., Geurts R., Goedert B. (2011) Length-to-width ratios among fancy shape diamonds. G&G, Vol. 47, No. 2, p. 129. Reinitz I.M., Gilbertson A., Blodgett T., Hawkes A., Conant J., Prabhu A. (2024) Observations of oval-, pear-, and marquise-shaped diamonds: Implications for fancy cut grading. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 280–304, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.3.280 |

GIA “Excellent” Fancy Recutting Solutions

Janak Mistry (Lexus, Surat, India) looked forward to the introduction of GIA’s fancy cut grading system, noting that the industry must prepare to manufacture fancy cut diamonds to “nicer makes” that receive better grades from the new GIA system and appeal to well-educated buyers. Leading laboratories have certified 8–10 million fancy-shaped diamonds over the last two decades. The majority were polished to retain mass rather than to optimize beauty and will likely require recutting to match clients’ expectations. A similar challenge arose in 2005–2006 when AGS and GIA introduced cut grading for round brilliants, prompting some manufacturers to recut inventory.

Mistry’s talk explored the implications of fancy cut grading through case studies on light performance and potential recut strategies. To demonstrate this process, Mistry selected a number of diamonds that performed poorly in the proposed new GIA system (beta version) and recut them to a GIA Excellent cut grade. The first example was a 0.51 ct oval with a very strong dark “bow tie” pattern. The best recutting plan option in the new system reduced the weight by 0.04 ct but removed the bow tie and improved the cut and symmetry grades to Excellent, resulting in a value addition of 22% and a far more marketable gem. The second example was a 0.96 ct emerald cut with Very Good cut, Fair symmetry, and Good polish. Its clarity was only I1 due to a deep cavity on the gem’s table. Recutting to the best solution reduced weight by almost 0.14 ct, but resulted in the removal of the cavity, which improved clarity from I1 to SI2, produced Excellent grades for cut, symmetry, and polish, and made the gem much brighter and pleasingly symmetrical. Mistry noted that the combination of these improvements was a value addition of 73%.

REFERENCES |

|

Moses T.M., Johnson M.L., Green B., Blodgett T., Cino K., Geurts R.H., Gilbertson A.M., Hemphill T.S., King J.M., Kornylak L., Reinitz I.M., Shigley J.E. (2004) A foundation for grading the overall cut quality of round brilliant cut diamonds. G&G, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 202–228, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.40.3.202 Reinitz I.M., Gilbertson A., Blodgett T., Hawkes A., Conant J., Prabhu A. (2024) Observations of oval-, pear-, and marquise-shaped diamonds: Implications for fancy cut grading. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 280–304, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.3.280 |

GEM CHARACTERIZATION

Rare and Radiant: The Science and Beauty of Fancy-Color Diamonds

Dr. Sally Eaton-Magaña (GIA, Carlsbad) explored the rainbow of natural diamonds and their varied causes of color, highlighting some of the most rare and magnificent diamonds that GIA has evaluated. Every natural diamond has a unique story of its creation written into its atomic-scale defects and inclusions (figure 11). Most receive the ingredients for color within the earth as they form. Impurities of nitrogen, boron, nickel, and hydrogen produce yellow, yellowish green, violet, and blue colors, while abundant tiny inclusions create black or white colors. Once they reach the earth’s surface, diamonds can be exposed to radioactive minerals that might color them green or blue. By contrast, the majority of natural pink diamonds colored by the 550 nm absorption band derive their color from the geologic forces of mountain-building events deep within the earth.

Natural yellow diamonds are the most common fancy colors, while pure orange diamonds are among the rarest. Both are colored by atomic-level structural defects associated with nitrogen impurities. Four groups of defects cause color in nearly all yellow and orange diamonds: cape defects (N3 and associated absorptions), isolated nitrogen defects, the 480 nm visible absorption band, and H3 defects. Some of the spectacular yellow to orange diamonds seen at GIA include the 30.54 ct Arctic Sun, the 128.54 ct Tiffany Yellow, and the 5.54 ct Fancy Vivid orange Pumpkin.

Natural blue diamonds are among the rarest and most valuable gems, and many come from very specific mines: South Africa’s Cullinan and Australia’s Argyle. While boron impurities are often associated with blue color, some blue and gray to violet colors also originate from simple structural defects produced by radiation exposure or from more complex defects involving hydrogen. Examples of remarkable blue diamonds include the 45.52 ct Hope, the 31.06 ct Wittelsbach-Graff, the 15.10 ct De Beers Blue, and the 20.46 ct Okavango Blue.

Dr. Eaton-Magaña then discussed the four major causes of color for green diamonds. Radiation exposure is the most common and can create vivid pure green colors. Some yellow-green diamonds owe their bodycolor to the combination of the H3 defect and green fluorescence, or to hydrogen- or nickel-related defects. Among the most famous green diamonds are the 41 ct Dresden Green, the 5.51 ct Ocean Dream, and the 5.03 ct Fancy Vivid green Aurora Green.

There are two primary causes of color for pink to red diamonds. The so-called “Golconda” pinks get their color from nitrogen vacancy centers, while the overwhelming majority of natural pink diamonds (about 99.5%) get theirs from an absorption band centered on 550 nm. This absorption band is created when the diamond experiences stresses at high pressure and temperature and plastically deforms, typically due to mountain-building events. The 34.65 ct Fancy Intense pink Princie, the 11.15 ct Fancy Vivid pink Williamson Pink Star, the 5.11 ct Moussaieff Red, and the 2.33 ct Winston Red are examples of famous pink to red natural diamonds GIA has examined over recent years.

REFERENCES |

|

Breeding C.M., Shigley J.E. (2009) The “type” classification system of diamonds and its importance in gemology. G&G, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 96–111, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.45.2.96 Breeding C.M., Eaton-Magaña S., Shigley J.E. (2020) Naturally colored yellow and orange gem diamonds: The nitrogen factor. G&G, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 194–219, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.56.2.194 Eaton-Magaña S., Breeding C.M., Shigley J.E. (2018) Natural-color blue, gray, and violet diamonds: Allure of the deep. G&G, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 112–131, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.54.2.112 Eaton-Magaña S., Ardon T., Smit K.V., Breeding C.M., Shigley J.E. (2018) Natural-color pink, purple, red, and brown diamonds: Band of many colors. G&G, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 352–377, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.54.4.352 Eaton-Magaña S., Ardon T., Breeding C.M., Shigley J.E. (2019) Natural-color fancy white and fancy black diamonds: Where color and clarity converge. G&G, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 320–337, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.55.3.320 |

The Impact of Fluorescence on the Appearance of Gemstones

Dr. Christopher M. Breeding (GIA, Carlsbad) explained that fluorescence in minerals has long been a subject of intrigue and fascination. For gemstones, it is sometimes considered a benefit and other times a flaw. Fluorescence can affect the appearance of some gemstones, and thus their values, even in normal lighting conditions. Dr. Breeding defined fluorescence as the emission of electromagnetic radiation from a substance stimulated by the absorption of incident electromagnetic radiation. The emission persists only as long as the stimulating radiation is continued. Phosphorescence is any emission that continues after the stimulating radiation is stopped. In gemology and mineralogy, fluorescence is commonly associated with excitation by an ultraviolet (UV) light source. Gemologists use a number of specific wavelengths of UV light, including long-wave at 365 nm, short-wave at 254 nm, and deep-UV (<230 nm, as used by the DiamondView device). Any wavelength of light, including visible light, can induce fluorescence.

Dr. Breeding noted that connoisseurs consider rubies from Myanmar’s (formerly Burma’s) Mogok region among the finest available. They owe their vibrant red hues to a combination of absorption and fluorescence, both caused by chromium atoms in their structure (figure 12). The trade values strongly fluorescent “Pigeon’s Blood” Burmese rubies, and the most exceptional stones have sold for more than US$1 million per carat. Rubies with high iron levels have weak fluorescence, and the trade tends to value them less highly. Research at GIA using filters that only allow chromium fluorescence to pass through shows that the impact of fluorescence on ruby’s red color may be overstated.

Conversely, the trade applies discounts of 10 to 30% to colorless or near-colorless diamonds with strong or very strong fluorescence. Dr. Breeding noted a common trade perception that D–G color diamonds with strong fluorescence sometimes exhibit a noticeable luminescence, which can give a diamond a “hazy” appearance. As a result, many near-colorless diamonds sell at a discount simply because they have strong blue fluorescence. Observations at GIA among high clarity, D–G color, highly fluorescent diamonds demonstrate that facet junctions remain clear and crisp under UV lighting. On the other hand, the hazy or cloudy appearance in fluorescent diamonds intensifies under UV. Strong blue fluorescence does not cause a diamond to appear hazy on its own, but it may increase the haziness of a stone with light scattering structural defects or inclusions. Experiments using a technique called modulation transfer function (MTF), which measures an optical system’s ability to transfer contrast from an object to an image, allow us to evaluate and quantify haziness in diamond. GIA will add comments to grading reports for many fluorescent diamonds beginning in late 2025.

To conclude, Dr. Breeding explained that pearls can be treated with blue-fluorescing optical brighteners to enhance their appearance, and that perceptions about gemstone fluorescence and appearance, even deeply rooted ideas, are not always reality.

REFERENCES |

|

D’Haenens-Johansson U.F.S., Eaton-Magaña S., Towbin W.H., Myagkaya E. (2024) Glowing gems: Fluorescence and phosphorescence of diamonds, colored stones, and pearls. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 560–580, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.4.560 Zhou C., Tsai T.-H., Sturman N., Nilpetploy N., Manustrong A., Lawanwong K. (2020) Optical whitening and brightening of pearls: A fluorescence spectroscopy study. G&G, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 258–265, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.56.2.258 |

Phenomenal Gemstones: A Brief Overview of the Nanostructures Behind the Optical Spectacles

Dr. Shiyun Jin (GIA, Carlsbad) focused on gem materials that display special optical phenomena including asterism, chatoyancy, aventurescence, iridescence, and color change. Gems with these distinctive properties have attracted the attention of gem lovers and scientists for centuries. Yet scientists have only characterized most of the nanostructures underlying these optical effects in the last few decades, thanks to the development of electron microscopy. Dr. Jin referred to the Summer 2025 Gems & Gemology paper, a comprehensive 60-page article documenting more than two dozen types of phenomenal gems with nearly 300 references for those seeking to know more. Dr. Jin noted that the paper provides necessary clarifications because many terms used in the trade to describe phenomenal gems are often poorly defined and subjective. However, the roots of this confusion are understandable: a gemstone might display multiple phenomena; gemologists often use many terms to describe the same phenomena; the same phenomenon might also look dissimilar in different stones; and different phenomena, with disparate underlying causes, may appear similar.

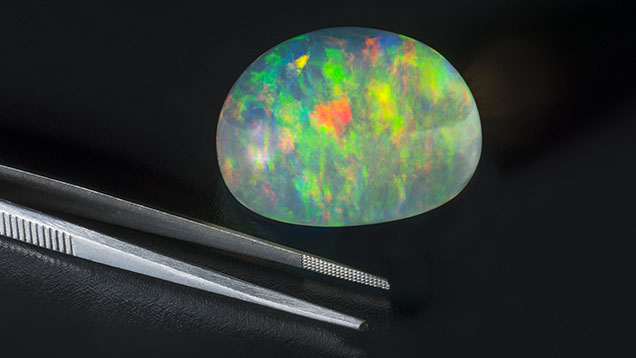

Dr. Jin briefly touched on well-understood phenomena including opalescence (the milky or hazy appearance due to diffuse scattering of light by nanoparticles), asterism and chatoyancy (the star and cat’s-eye effects caused by oriented light-scattering needles), and aventurescence (the specular reflections from isolated, typically flat or “platy” inclusions within a transparent gem). A longer segment of the talk covered phenomena due to thin-film interference of reflected light from repeated arrays of transparent thin platy minerals, where the color depends on the thickness of the layers. This includes the blue flashes of labradorescence, the rainbow of orient or overtone shown by nacreous pearls, the iridescence of shell, and play-of-color in opals (figure 13). Iridescence is not exclusive to gems; the flashing colors seen in a pigeon’s feathers, a butterfly’s wing, or on the surface of a soap bubble are due to the same cause.

Next, Dr. Jin focused on inconsistencies in terms mineralogists, gemologists, and the gem trade use to describe feldspars with iridescence. Mineralogists generally separate iridescent feldspars into three categories based on their bulk chemical composition: labradorite, peristerite, and moonstone. Moonstone, for example, is named after its white or silver iridescent glow that resembles moonlight. Unfortunately, the trade applies the term moonstone haphazardly to any light-colored feldspar, such as transparent labradorite displaying a desaturated multicolor iridescence, which is often sold as “rainbow moonstone.” This adds confusion to an already complicated subject. Dr. Jin encouraged the use of more general terms such as iridescence and play-of-color over specific terms such as labradorescence. He stressed that phenomena should be defined based on the underlying texture and physics processes instead of vague descriptions of appearance.

REFERENCE |

|

Jin S., Renfro N.D., Palke A.C., Shigley J.E. (2025) Structures behind the spectacle: A review of optical effects in phenomenal gemstones and their underlying nanotextures. G&G, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp. 110–170, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.61.2.110 |

GENERAL GEMOLOGY

The Science That Makes Gems Shine: Understanding Metrology at GIA

Dr. Yun Luo (GIA, Carlsbad) began by differentiating metrology, the science of measurement and its application, from meteorology, the study of the weather, and explaining its relevance to GIA. Dr. Luo explored how metrology underpins GIA’s research and laboratory services through rigorous validation, verification, and intra- and inter-laboratory testing of various measurement instruments. Precision and accuracy are at the heart of every gemstone measurement and evaluation GIA undertakes. Metrology ensures consistency and reliability across GIA’s global laboratories. Dr. Luo explained how the three pillars of traceability (every result must link back to a recognized reference), reference standards (the agreed reference everyone measures against), and accuracy (how close a measurement is to the true value) ensure that the measurements of a diamond taken at one GIA laboratory match those of the same diamond if submitted to another GIA location. Dr. Luo defined accuracy as the closeness to a desired target value and precision as the consistency and repeatability of the results achieved. Both are essential for reliable measurements. Uncertainty is the level of confidence we have in the result, and calibration is the process of correcting systematic error. Together, precision, uncertainty, and calibration transform a number on a screen into a scientifically sound and meaningful measurement. Dr. Luo reminded the audience that measurement without an estimate of uncertainty is meaningless.

Every instrument has a range of reproducibility or tolerance. Reproducibility measurements allow metrologists to track the performance of each device and assess whether any of them need extra attention. Testing a gemstone at GIA includes measurement of carat weight, dimensions, color, clarity, fluorescence, spectrometry, imaging, and chemical analysis. These measurements have to be accurate, precise, and consistent across all of GIA’s labs. What makes GIA stand out is that metrologists verify instruments daily before evaluating client stones, regularly submit unannounced blind control stones to check accuracy, have well-defined standards and inter-lab tests for global consistency, and capture hourly data during business hours at all GIA laboratories to ensure quality.

REFERENCE |

|

Nelson D.P., Reinitz I.M. (2024) Metrology at GIA. G&G, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 596–603, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.60.4.596 |

The Vault and Beyond: The Exciting Lives of Museum Specimens

Dr. Rachelle Turnier (GIA, Carlsbad) offered a behind-the-scenes look at the GIA Museum to highlight the essential roles its exhibits and specimens play in GIA’s mission. When Robert M. Shipley founded GIA in 1931, he needed specimens for teaching. In those early days, there was no distinct “museum,” but rather simply an “education collection.” Over the years, the collection grew as diamonds and gemstones were loaned or purchased. Eventually some of the loans became gifts. In 1976, Dr. Vincent Manson, GIA’s “director of dreams,” had a vision for separate museum and education collections. A former curator at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, he recognized the value of GIA’s pieces and their many potential uses and separated them into two collections.

However, it was not until 2000 that GIA created a formal museum department. The catalyst was undoubtedly the 1997 opening of the Carlsbad campus. GIA is a living museum, with more than 100 exhibits spread throughout the Carlsbad campus to serve the students, public, and employees. Of the 50,000 specimens in the collection, 75% are donations from alumni, industry leaders, and retiring enthusiasts who donate their treasures knowing they will be used and appreciated (figure 14). The Sir Ernest Oppenheimer Student collection is perhaps the most foundational donation. Loaned in 1933, then later donated in 1955, it consists of more than 1,500 carats of diamonds, worth $20,000 at the time. Its spectacular diamond crystals, both loose and in matrix, would be valued at several million dollars if donated today. Through donations and purchases, GIA acquired additional important collections including the Dr. Kurt Nassau Synthetic collection, the Dr. Frederick H. Pough Synthetic collection, a collection of Pierre Touraine’s Southwest-inspired jewelry, and in 2005, the Dr. Edward J. Gübelin collection. Recent donations include pre-Columbian jewelry, a collection of 850 polished gem and mineral eggs, the models and findings of Peter Lindeman, who worked for important jewelry brands including Tiffany & Co., and a significant donation of high-end jewelry ranging from an Egyptian necklace fabricated around 1500 BCE to Victorian high-end jewelry from brands such as Cartier, Tiffany & Co., and Fabergé.

While GIA’s Museum collection serves to educate students and inspire visitors on public tours, it is also a crucial resource for GIA’s scientists. GIA researchers draw on the collection for experiments and research purposes, including using gemstones of known localities to develop new geographic origin services, studying gems for causes of color, and even for developing laboratory standards.

REFERENCES |

|

GIA Museum: https://www.gia.edu/gia-museum |

Exploring the Behind-the-Scenes of the Smithsonian National Gem Collection

Dr. Gabriela Farfan (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC) shared how research, “behind-the-scenes” teams, and iconic exhibits work together to spark curiosity about the natural world, highlighting the new Winston Fancy Color Diamond collection—including the 2.33 ct Winston Red—which was unveiled in 2025. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History is part of the U.S. national collection of museums, has no admission charge, and sees more than 6 million visitors per year. Its gems and minerals are a gateway to science for many visitors. In Dr. Farfan’s reckoning, a gem is a mineral that has been transformed by an artist, and the Institution’s many such gem icons include the 45.52 ct Hope diamond, the 48.68 ct “Whitney Flame” topaz, the 10,363 ct Dom Pedro aquamarine, the 75.47 ct Hooker emerald, and the Marie Antoinette diamond earrings. Dr. Farfan noted that the National Gem and Mineral Collection contains approximately 385,000 specimens, of which more than 10,000 are gemstones. The Institution’s role is to preserve mineral and gem specimens for generations to come.

Although all the Smithsonian’s specimens come via donations, other museums may request loans for exhibits, and scientists can request samples for study. Recent acquisitions include the 55.08 ct Kimberley diamond (2019); the 116.76 ct “Lion of Merelani” tsavorite garnet (2023); a 30.50 ct spessartine garnet, a 12.85 ct bicolor zoisite, a spectacular morganite carving of cockatoos (2024); and a 13.34 ct Paraíba tourmaline and a 73.55 ct lavender spinel (2025). Dr. Farfan explained how the collection is expanded by filling its “holes.” This includes adding new mineral species, covering representation of specific localities, responding to popular research topics, including unique gemstones, and making significant “upgrades” for exhibitions. The Winston Fancy Color Diamond collection donated in 2025 is one such example. It encompasses 118 diamonds in all colors of the rainbow. Forty of these diamonds, ranging from 0.4 to 9.5 ct, are now on exhibit. Of these, the Winston Red, a 2.33 ct old mine brilliant cut diamond with an unmodified Fancy Red hue, is the most well-known.

A group of researchers from the Smithsonian, GIA, and the École des Mines de Paris (Paris School of Mines) undertook a 2025 study of the Winston Red to answer specifics about the gem, namely the cause of its unique pure red hue, and its history, geographic origin, and rarity. Dr. Farfan outlined the results of the team’s research. Analyses confirmed the presence of plastic deformation bands, and dislocation network patterns classified the Winston Red as a type IaAB (A) Group 1 “pink” diamond. To achieve its red color and dense dislocation networks, the Winston Red diamond likely experienced immense strain in Earth’s mantle. Although the team traced the Winston Red back to 1938, its old mine brilliant cut suggests a richer story. Based on its mineralogical characteristics and history, Dr. Farfan concluded that the likely geographic origin of the stone is Venezuela or Brazil and called out the recent Spring 2025 Gems & Gemology article on the gem.

REFERENCES |

|

Chapin M., Pay D., Shigley J., Padua P. (2013) The Smithsonian gem and mineral collection. GIA Research News, November 14, https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-smithsonian-gem-mineral-collection Crowningshield R. (1989) Grading the Hope diamond. G&G, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 91–94. Farfan G.A., D’Haenens-Johansson U.F.S., Persaud S., Gaillou E., Feather R.C. II, Towbin W.H., Jones D.C. (2025) A study of the Winston Red: The Smithsonian’s new fancy red diamond. G&G, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 16–42, http://dx.doi.org/10.5741/GEMS.61.1.16 Gaillou E., Post J.E. (2007) An examination of the Napoleon diamond necklace. G&G, Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 352–357. King J.M., Shigley J.E. (2003) An important exhibition of seven rare gem diamonds. G&G, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 136–143. |

NEW TECHNOLOGIES AND TECHNIQUES

Revealing the Hidden World of Diamond in 3D

Dr. Daniel Jones (GIA, New Jersey) explained that all diamonds possess an interior “hidden world” that reveals their growth history, information about their chemical composition, and evidence of post-growth events. In this talk, Dr. Jones explored the unseen world of diamond, showing the structures of growth using photoluminescence with a newly developed GIA 3D imaging system. This system allows for high-resolution 3D mapping of the internal structure of diamonds using defect photoluminescence and high-powered lasers. It also identifies defects using spectroscopy.

Natural diamonds grow deep in the earth over a period of millions to billions of years and are subject to changing environments, which cause subtle, sometimes imperceptible changes to their atomic structure. Dr. Jones asked the audience to liken diamond growth to tree rings, showing layers radiating outward with the oldest part in the center. A diamond’s growth history can be viewed using complex imaging techniques. Dr. Jones remarked how visual observations can be useful in analyzing diamond, and that spectroscopy, a method for determining the existence of atomic-scale color centers, can be applied across the bulk or at specific points of a diamond. Some of these color centers create visible color through absorption, and others emit light through fluorescence when excited via a laser light source. Using a combination of visual observation, spectroscopy, and 3D scanning, gemologists can visualize the structures of natural diamonds in their full crystallographic majesty.