Multilayered Laboratory-Grown Diamond

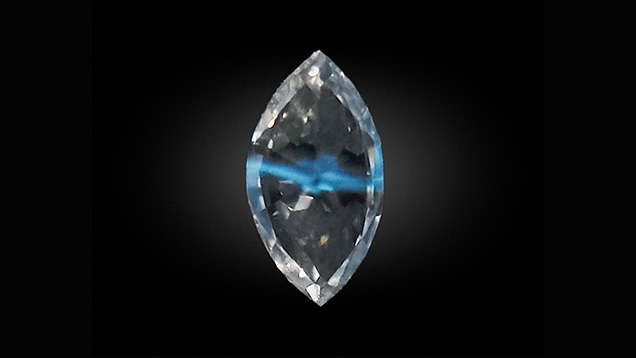

A marquise-shaped laboratory-grown diamond weighing 0.07 ct and measuring 4.20 × 2.26 × 1.27 mm was recently submitted to Stuller’s gemological laboratory for testing. The near-colorless (G–H color range) and very slightly included (VVS2–VS1) stone provided some unusual results.

Deep-UV excitation (<225 nm) of the laboratory-grown diamond produced a multicolored pink-orange fluorescence accented by the dislocation bundles’ vein-like pattern toward the long pointed edges and a thin (<50 μm) greenish blue layer crossing the center of the stone vertically from the table facet to the pavilion (figure 1). Viewed separately using broad-range pulsed xenon (120–2000 nm) and short-wave UV (254 nm) imaging, it exhibited a persistent (>5 s) zone of greenish blue phosphorescence in the same location as the previously mentioned greenish blue fluorescent layer (figure 2).

When viewed with crossed polarizing filters, a strain in columnar and cross-hatched patterns was easily observed, though a thin layer of dark solid color was also observed. The section with the solid strain was once again consistent with the area of fluorescence and phosphorescence. Infrared spectroscopy revealed indications of uncompensated boron at 4092, 2929, 2803, and 2452 cm–1, and no nitrogen was detected (figure 3). Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy under liquid nitrogen (77K, –196°C), using 532 nm laser excitation, showed differences between areas within the stone. When the laser was focused on the long edges, sharp peaks at 575 and 637 nm (the NV0 and NV– centers, respectively) were observed, with the former being stronger. The NV0 and NV– centers are shown in figure 4, labeled “side A” and “side B,” respectively. Also, weak SiV– lines at 737 nm were detected on both edges. When the laser was focused on the thin layer labeled “center” in figure 4, the NV0 and NV– zero-phonon lines were significantly reduced and no SiV– was detected.

The distinctive fluorescence and phosphorescence patterns observed under deep-UV, short-wave UV, and xenon imaging, as well as the presence of zonal dislocation bundles, strain characteristics, and PL spectra differences, suggest a complex growth process involving multiple layers.

NV0 causes orange-red fluorescence in deep UV, a typical property of diamonds grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) without post-growth high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) treatment (P.M. Martineau et al., “Identification of synthetic diamond grown using chemical vapor deposition,” Spring 2004 G&G, pp. 2–25). The green-blue fluorescence and long-term phosphorescence reaction to deep UV is associated with both HPHT-grown and CVD-grown diamonds, while the infrared spectrum and long-term phosphorescence under short-wave UV are associated with boron impurities. These features are typical properties of HPHT-grown diamonds (C.M. Welbourn et al., “De Beers natural versus synthetic diamond verification instruments,” Fall 1996 G&G, pp. 156–169; K. Watanabe et al., “Phosphorescence in high-pressure synthetic diamond,” Diamond and Related Materials, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1997, pp. 99–106), but can also point to the phosphorescence seen in boron-incorporated type IIb CVD-grown products and interfaces between CVD growth layers (S. Eaton-Magaña et al., “Observations on HPHT-grown synthetic diamonds: A review,” Fall 2017 G&G, pp. 262–284; S. Eaton-Magaña, “Summary of CVD lab-grown diamonds seen at the GIA laboratory,” Fall 2018 G&G, pp. 269–270; S. Eaton-Magaña et al., “Laboratory-grown diamonds: An update on identification and products evaluated at GIA,” Summer 2024 G&G, pp. 146–167).

The strain shown in two patterns on each side of the stone was consistent with CVD growth (E. Fritsch et al., “‘Birefringence’ in diamond: A useful tool to separate natural from synthetic diamond,” 32nd International Gemmological Conference IGC. Interlaken, Switzerland, July 13–17, 2011, pp. 71–72). However, the pattern difference indicates that each layer was created separately. In addition, the thin layer in the center showed a dark solid strain. This layer’s dark appearance could be due to an elastic strain applied to the neighboring layers, possibly masking a thin, strain-free area commonly observed in HPHT-grown diamonds.

Infrared spectroscopy using the DRIFT technique confirmed a type IIb diamond structure, mostly typical of colorless to near-colorless HPHT-grown diamonds (Eaton-Magaña et al., 2017) or boron-incorporated type IIb CVD-grown diamond (Eaton-Magaña et al., 2024). Also, the nitrogen vacancies’ peak changes between layers, observed using PL, could be the result of an HPHT process in the center thin layer or different growth conditions in the CVD feed gas during start-stop cycles (Eaton-Magaña, 2018). Considering the relatively high boron detected, contamination due to HPHT annealing seems unlikely. Hence, the center layer was either grown using an HPHT method or formed as a boron-rich CVD layer during a multi-stage growth.

These results highlight the stone’s heterogeneous composition. The findings suggest a multilayered synthetic diamond, with either three distinctly different CVD growth layers or two CVD layers on both ends of the stone and a thin HPHT layer between them. This case highlights the challenges of discerning the intricacies of diamond synthesis. As more consumers request a specific growth method and gemological laboratories state the synthesis method on their gemological reports, a quick analysis or a simple screening machine might give unclear results and not be sufficient to distinguish between mixed-growth diamonds and those grown using a single process.

.jpg)