Gem Granitic Pegmatites

Granitic pegmatites have long attracted attention as important sources of valuable minerals and gems (table 1), while also representing somewhat of a conundrum for geoscientists trying to understand their geological origin. Occurring in various parts of the world, they are significant producers of gem tourmaline, beryl, spodumene, topaz, and garnet (figure 1; Simmons et al., 2012) along with mineral specimens. They are also valuable sources of bulk industrial products such as quartz, feldspar, mica, and columbite-tantalite ores (e.g., coltan). For more than a century, pegmatites have been the focus of scientific studies to better understand the geological conditions of their formation and the reasons for their diverse mineralogy, rock texture, and overall structure.

The renowned French mineralogist René-Just Haüy (1823, p. 536) defined the word pegmatite as “feldspath laminaire avec cristaux de quarz enclaves” (laminar feldspar with enclosed quartz crystals), using it as a rock textural term and as a synonym to describe igneous rocks that displayed a pronounced intergrowth of tabular or skeletal quartz crystals in a feldspar host—rocks that up until then were often referred to as “graphic granite.”

According to London (2008, p. 4), the name pegmatite comes from the Homeric Greek word πήγνυμι (pēgnymi), which means “to bind or to fasten together.” Again its use was related to describing graphic granite, where the pattern of darker glassy quartz crystals embedded in a lighter perthitic feldspar host could vaguely resemble ancient written characters.

Austrian mineralogist Wilhelm Karl von Haidinger (1845, p. 585) first used the term pegmatite in its present geological meaning for coarse-grained igneous rocks, but he still related it to graphic granite. He defined pegmatite as coarse-grained feldspar-rich granite; the individual quartz crystals in the feldspar are mixed in crystalline symmetrical layers, so that slices (broken surfaces) look similar to written script.

This term is now used generally to refer to most coarse-grained igneous rocks. London (2008, p. 4) provided a more specific definition: “an essentially igneous rock, commonly of granitic composition, that is distinguished from other igneous rocks by its extremely coarse but variable grain size, or an abundance of crystals with skeletal, graphic or other strongly directional growth habits. [They] occur as sharply bounded homogeneous to zoned bodies within [more voluminous] igneous or metamorphic host rocks.” This definition focuses on the textures of these rocks, which are their most distinctive features. Books by London (2008), Simmons et al. (2022), and Menzies and Scovil (2022) provide information on their geology, formation, and occurrence. Past geological reviews of these topics were provided by Landes (1933), Cameron et al. (1949), Jahns (1955), Černý (1982), Simmons and Webber (2008), and Dill (2015 and 2016).

This edition of Colored Stones Unearthed will describe pegmatitic igneous rocks and their geology, mineralogy, and current understanding of their conditions of formation, as well as summarize their worldwide occurrences. The column will focus on granitic-composition pegmatites, which are the most common type and the major sources of gem-quality crystals.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

Granitic pegmatites are bodies of coarse- and sometimes associated fine-grained (aplites), light-colored, intrusive igneous rocks composed of interlocking crystals of several common minerals (mainly quartz, alkali feldspar, and mica; see figures 2 and 3) that are sometimes accompanied by rare element–bearing minerals. Their bulk chemical compositions correspond closely to those of familiar non-pegmatitic plutonic igneous rocks. Within pegmatite bodies, the constituent minerals can span several orders of magnitude in size from small grains to large individual crystals (a much greater range of grain size than would be encountered in an ordinary granite). Pegmatites are noteworthy for having produced some of the largest-known crystals—in particular microcline, quartz, mica, spodumene, and beryl—that have reportedly reached up to 10 meters or more in length (Rickwood, 1981). As implied by the early definitions of nineteenth-century scientists, one of the most unique textural features of granitic pegmatites is the intergrowth of quartz and feldspar crystals mentioned above as “graphic granite.”

Basic, intermediate, and alkaline igneous rocks can sometimes also display similar pegmatitic textures. They include pegmatitic gabbro, syenite, and nepheline syenite, all of which are composed of minerals such as pyroxene, plagioclase feldspar, mica, olivine, hornblende, and nepheline. Figure 4 illustrates a large corundum (sapphire) crystal embedded in a syenitic pegmatite from the Ilmen Mountains in Russia.

Structure. Pegmatites exhibit a diverse variety of shapes, sizes, and internal structures. They can occur as narrow dikes (figure 5), sills, veins, or more oval-shaped bodies found within larger parental intrusive igneous host rocks. They can also extend outward as veins within other surrounding metamorphic or igneous host rocks. Often minor in size compared to the enclosing rocks, they are centimeters to meters or more across and less than a meter up to a kilometer or more in length (figure 6). The pegmatite edges are often marked by distinct boundaries. Multiple pegmatite dikes may occur within the same host rock.

In terms of internal structure, they fall into two categories. The majority are referred to as simple pegmatites, which are more homogeneous in mineralogy—they lack any internal mineral zoning and are composed of the same common minerals found in other silica-rich igneous rocks like granites. Their main difference from the host rocks is their coarser grain size.

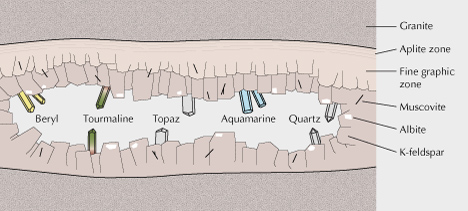

Complex pegmatites are composed of these same minerals, often along with rare and unusual minerals (such as beryl, tourmaline, and many others). They display an inhomogeneous texture with several layered, vertical, or concentric internal zones of different minerals and mineral grain sizes, and central zones that may contain open crystal-filled cavities (figure 7). Grain size generally increases inward from the margins toward the center of the pegmatite body. Concentric zoning is typical in an oval-shaped body, while internal zoning in a horizontal dike can be more asymmetric (figure 8). Distinct zonation is typically better developed and more evident in larger pegmatites because of the opportunity for greater differentiation of the residual magma and fluids during magma crystallization. Again, internal zones form from the outer edge inward, with the core being the final zone to solidify from the magmatic fluid.

In a complex pegmatite, internal zones can often be recognized by increasing mineral grain size, but they can vary in thickness and mineral composition. From the outside inward, the zones follow this sequence:

- A thin border zone where the pegmatite magma came into contact with the preexisting host rock

- A thicker wall zone consisting of feldspar and quartz

- An intermediate zone that is richer in feldspar and contains occasional crystal-lined cavities

- A core zone consisting of massive quartz and occasional crystal-lined cavities

PEGMATITE FORMATION

The occurrence, mineralogy, texture, and structure of pegmatites have long attracted the attention of geoscientists, who have shared various theories of origin (Jahns, 1955). While scientific discussions of pegmatites date from the late 1800s, modern studies originated from several past interrelated trends:

- The laboratory studies of fractional crystallization in igneous magmas pioneered by Bowen at the Geophysical Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution of Science in Washington, DC, from 1912 to 1937. His 1928 book entitled The Evolution of the Igneous Rocks provided the geochemical and geophysical foundation for the petrological study of igneous rocks and minerals and their conditions of formation. London (1992 and 2008) summarized past ideas and more recent experimental work on granitic pegmatite formation by his group and other researchers.

- The wealth of valuable minerals found in pegmatites in Madagascar that were described in detail by Lacroix based on his visit to the island in 1911 (Lacroix, 1922a,b, 1923).

- The description of the extensive occurrences of nepheline syenite pegmatites in southern Norway by Brögger (1890; also Müller et al., 2017).

- The field studies of pegmatite occurrences in Brazil, the United States, and elsewhere undertaken in the 1940s and 1950s to document the occurrence of rare elements such as tantalum in demand for industrial use during and after World War II (Johnston, 1945; Hanley et al., 1950; Page et al., 1953; Cameron et al., 1954; Jahns, 1955).

Most granitic pegmatites form relatively close to the earth’s surface, and they occur either within or near the upper portions of a genetically related larger body of igneous parent rock called a pluton. The magmas that might eventually produce pegmatite bodies were generated by the melting of crustal rocks and pluton formation in two different geological settings. The first—referred to as orogenic magmas—formed during the compressive collision of crustal plates, which created mountain chains along the collision boundaries. The magmas formed along the collision zone produced granitic rocks that comprise a large proportion of the currently exposed crustal surface. The second—called anorogenic magmas—formed during the stretching and thinning of crustal plates that are being pulled apart. The shallow underlying presence of a volume of heated mantle causes melting and magma formation within the extended overlying portion of the plate. The variety of igneous rocks produced by these anorogenic magmas are more restricted in occurrence as sources of gem-bearing pegmatites. Some so-called anatectic pegmatites appear to have formed by the melting of metamorphic parent rocks since they have no obvious connection to an igneous pluton.

Based on field observations and experimental studies, granitic pegmatites are believed to have crystallized in the continental crust from relatively small volumes of a separate residual hydrous- and volatile-rich magmatic fluid fraction that remained during the solidification of a larger granitic magma body. During the final stages of pegmatite formation, this magmatic fluid is thought to have coexisted in small volumes with the residual pegmatitic magma. Pegmatite evolution and final crystallization involves a series of processes including fractional crystallization of minerals, immiscibility within the residual melt, the increasing influence on mineral formation of alkali and halogen contents and enrichment of so-called incompatible elements (i.e., rare earth elements (REE), tantalum, niobium, lithium, and beryllium), and the exsolution of a hydrothermal aqueous fluid phase (Pauly et al., 2021).

The bulk compositions of pegmatites are similar to the compositions of the magmas from which they form. Whether or not a particular granitic magma will generate pegmatites depends in large part on the needed presence of chemical components such as boron, phosphorus, and fluorine as well as excess amounts of water in the magma (Černý et al., 2012). The model of granitic pegmatite formation described by Jahns and Burnham (1969) envisioned the transition from granite to pegmatite formation being marked by the exsolution of an aqueous fluid from the silicate melt and the partitioning of chemical components between these two phases. Subsequent experimental work on pegmatite mineral systems and studies of the compositions of fluid inclusions in late-stage pegmatite minerals have brought some concepts of this genesis model into question.

When this residual hydrous magmatic fluid forms within the cooling granitic pluton itself or is injected into fractures in the surrounding country rock, minerals begin to crystallize within the pegmatite body as temperatures decrease from the outside inward in a relatively static geological environment. The rapid cooling combined with the low residual heat content results in limited chemical interactions between the magmatic fluid and the surrounding host rocks (Černý et al., 2012).

Within the host granite, simple internally homogeneous pegmatites form from a trapped volume of the residual magma with a similar mineralogy, but they can display large variations in texture and mineral grain size. These rock bodies are often composed of approximately 65% alkali feldspar, 25% quartz, 5–10% mica, and about 5% other accessory minerals (Glover et al., 2012). They often lack rare ore minerals, but they are significant sources of common minerals such as feldspar. They are thought to represent a transition stage of magma crystallization between granites and rare-element pegmatites.

In contrast, complex pegmatites crystallize with the same bulk minerals but a more complicated internal structure and a more varied chemical and mineral composition. They crystallize from the outside contacts inward in the form of concentric or layered zones that often have different mineral assemblages and/or textures, sometimes ending with an almost monomineralic central quartz core (Norton, 1983). As crystallization proceeds, the chemical composition of this fluid fraction progressively evolves as solidifying minerals remove certain elements from, and other elements are concentrated in, the decreasing remaining fluid, which then allows new minerals to form.

These evolving residual magmatic fluids become enriched in volatile components and trace elements (water as hydroxyl (OH–)) and rare elements (such as lithium, beryllium, boron, fluorine, phosphorus, rubidium, zirconium, niobium, cesium, and tantalum) that are not incorporated for the most part in common minerals such as feldspar and quartz in earlier-forming igneous rocks. This rare-element fractionation and chemical enrichment result in the formation of a host of uncommon minerals in these complex pegmatites which are rarely, if ever, found in such abundance in other geological settings (thought to be more than 500 mineral species; Menzies and Scovil, 2022). The diversity has long attracted the attention of both geoscientists and mineral collectors.

In comparison to the initial silica-rich granitic magma, the residual mineralized aqueous fluid within the pegmatite body has a lower viscosity and melting point due to the increased presence of fluxing agents. At the lower temperatures of this stage of pegmatite formation, geologists believe that the rate of nucleation of tiny new crystals is slower than the rate of crystal growth, which tends to favor the growth of fewer but larger crystals. When trapped within the central core zone of a crystallizing pegmatite, isolated volumes of this increasingly water-rich fluid allow for the formation of one or more generations of well-formed, larger-size gem-quality crystals within open crystal-lined spaces or cavities as the final stage of crystallization. Recent work suggests that during this stage, crystal growth rates could have accelerated dramatically from millimeters to a meter or more per day (Phelps et al., 2020). Subsequent alteration and weathering of pegmatite feldspars and micas resulted in the formation of secondary clays, which often completely fill any remaining open space in the cavities and coat any crystals. These so-called miarolitic pegmatites occur within or near magmatic plutons that intruded to shallow depths in the crust; occasionally, they can also be found in migmatite terrain in anatectic pegmatites (Webber et al., 2019).

This diversity of size, occurrence, internal structure, rock texture, and mineralogy found in pegmatites presents challenges for geoscientists trying to unravel the story of these fascinating igneous rocks. The variety of pegmatite occurrences suggests that other geological processes may on occasion be involved in their formation beyond the volatile-rich magma crystallization model summarized above.

PEGMATITE CLASSIFICATION

The diversity of the more complex granitic pegmatites observed in the field has led geologists to propose various schemes to classify them based on features such as mineralogy, geochemistry, texture, shape, size, and/or relationship to host rocks. The trace element signatures of most rare-element pegmatites (containing elements such as lithium, beryllium, boron, niobium, yttrium, fluorine, and others) allow them to be grouped into two distinctive families, with occurrences of so-called lithium-cesium-tantalum (LCT) granitic pegmatites greatly outnumbering those of the niobium-yttrium-fluorine (NYF) family. For further discussion, see Černý and Ercit, 2005, and Černý et al., 2012. This classification scheme reflects the increasing complexity of internal zones and the chemical evolution of the pegmatite-forming magmas with distance from their source (London, 2008).

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE

Industrial Minerals. Although of lesser volumetric importance than other crustal igneous rocks, pegmatite bodies and dikes are major sources of both common and rare minerals. Hence, they are the focus of mineral collecting, as well as mining activities on both small and large scales, in various parts of the world.

Most pegmatites have a simple granitic composition and mineralogy, and their mining focuses on recovering feldspar, quartz, mica, beryl, and spodumene as well as certain high-value ore minerals (Glover et al., 2012). The overall chemical purity of these minerals and the very high percentage of mineable rock at a deposit make granitic pegmatites important mining targets. Several examples of localities mined for industrial minerals and for gem crystals are listed in tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Industrial minerals such as feldspar and quartz are mined in very large quantities. Once excavated and transported, the crushed ore is washed and then separated into specific minerals by various physical, electrical, magnetic, or flotation techniques. These mineral concentrates can then be further processed into particular chemical compounds depending on the final applications for the material, such as Li2O from bulk spodumene or petalite (Pripachkin et al., 2022; Kundu et al., 2023; Roy et al., 2023) and Ta2O3 from tantalite (Melcher et al., 2017a,b). These bulk materials have important industrial uses, such as in the glass and ceramic industries in the case of feldspar (figure 9).

Gems and Mineral Specimens. The conditions of granitic pegmatite formation result in several chemical elements occurring at much higher concentrations than in most other igneous rocks. In some situations, these concentrations are sufficient to allow these rare elements to occur as major constituents in distinct minerals (e.g., pollucite, a cesium aluminosilicate zeolite).

Some of the finest gem crystals and specimens from the mineral kingdom originate mainly and sometimes solely from complex, internally zoned pegmatites (Simmons et al., 2012). These gem minerals occur most often in open (or clay-filled) pockets in the core and central zones of the pegmatite body (figure 10). With diameters typically from centimeters to a meter or more, these pockets are more easily located in a thinner pegmatite dike but can be difficult to find in a thicker one.

Although pockets are normally encountered in the central zones of a pegmatite, their occurrence within that zone is often random and highly variable. Blasting, drilling, or breaking up the pegmatite body risks damaging valuable gem crystals, which influences the mining techniques used. Miners often look for minerals or rock textures as indicators of a nearby gem pocket. For example, one good indicator is the presence of lepidolite mica (many others are discussed by Menzies and Scovil, 2022). Miners have noted that pockets tend to occur where pegmatite dikes increase in thickness, change direction, or intersect. Such locations may have facilitated the formation of residual aqueous fluids. Nearby pockets can contain similar or very different gem minerals. Several stages of mineral formation may also be evident, and the distribution of mineral contents within pockets can be nonuniform. Some gem crystals show evidence of corrosion, partial dissolution, and mineral replacement.

These pockets are often filled partially or completely with secondary clays (figure 11), so miners use a pointed hand tool such as a screwdriver to gently probe the clay to detect if crystals are present (figures 12 and 13). Once a pocket is located, the contents are carefully removed by hand, and the clay-coated crystals are washed—only then does the miner know what exactly has been found. Crystals may still be attached to the pocket walls or lie as broken pieces on the pocket floor. Besides recovering individual gem crystals, efforts are made to extract attractive rock matrix specimens with the crystals still attached. Careful trimming and cleaning of matrix pocket specimens are often required.

Field-tested remote sensing techniques, such as ground-penetrating radar, can sometimes reveal the presence of an open cavity in a pegmatite body (Patterson and Cook, 2002; Cardoso-Fernandes et al., 2019). The article by Steiner (2019) discusses useful techniques for locating gem pegmatites. Pegmatite mining techniques vary in scale and sophistication depending on the type of occurrence, with work in many countries carried out by artisanal mining operations.

SUMMARY

Despite their typical small volumetric size, granitic pegmatites represent one of the most important producers of gem crystals along with both common and rare minerals (figure 14). Their varied mineralogy, external shape and internal texture, and widespread occurrence continue to attract the attention of geoscientists seeking to understand the geologic conditions of their formation. They continue to be found and mined wherever granite bodies are exposed at the earth’s surface, and they remain a major source of a number of valuable gem minerals.