Characterization of “Orange Peel” Surface Microstructure of White Nephrite from Russia: A Unique Pseudomorph Pattern

ABSTRACT

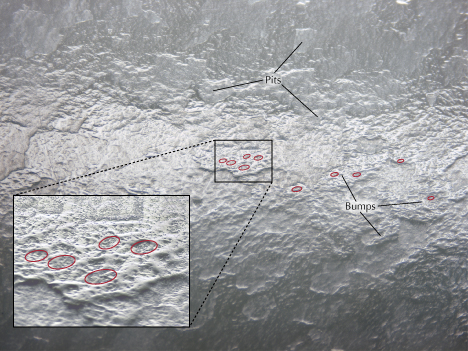

The term orange peel effect is often used to refer to the uneven appearance of the polished surface of jadeite, which arises due to the hardness anisotropy of its mineral grains arranged in different directions. The unusual orange peel effect observed on white nephrite from Russia has been preliminarily recognized in the commercial sphere, but minimal description of the underlying causes for the effect exists in the literature. In this investigation, this orange peel surface feature, which includes granular pits and bumps, pseudo-rhombic microstructure, and subparallel fissures, was explored using gemological and petrographic microscopes, an electron probe microanalyzer with backscattered electron imaging, and cathodoluminescence imaging. The observed surface feature, related to pseudomorphs, results from metasomatism where nephrite (tremolite) replaces rhombic carbonate (dolomite) mineral grains while preserving their original microstructure. Petrographic observations show that the pseudo-rhombs on these pseudomorphs are intersected by a network of veins, similar to the framework of cleavage patterns of calcite or dolomite. The pseudo-rhombs ranged from 100 to 500 μm in width, consisting of a thin vein outline and an inside region composed of fine compacted fibers, with a relatively less compact central domain. This study demonstrates that this effect is largely dependent on the nephrite’s adopted microstructure rather than its chemical composition or mineral components. Derived from these results, a formation model of this distinctive microstructure is proposed, arising from fluid flow and precipitation accompanied by volume shrinkage reactions during replacement progress. Based on the review of the microstructures of available white nephrite samples from other localities, the pattern of pseudomorphs with pseudo-rhombs and claw lineation is a unique feature of Russian nephrite.

Nephrite is mainly composed of aggregates of tremolite-actinolite. According to Bradt et al. (1973), high-quality nephrite is characterized by felted, matted, interwoven, and recrystallized microstructures and thus typically has high toughness. As a gemstone and ornamental material, nephrite played important roles in ancient Asian cultures and continues to do so in modern China. It has been considered a symbol of power and wealth, as well as a symbol of desirable moral qualities, including kindheartedness, righteousness, wisdom, courage, and purity, throughout history in Chinese culture (e.g., Cha, 2011). Because of its cultural meaning, white has been regarded by the Chinese as the most valuable color variety of nephrite. For instance, during the Song Dynasty of China, Emperor Zhenzong (997–1022) used a “white nephrite album of slips” (yùcè 玉册), a jade tablet that resembles an ancient bamboo scroll and is inscribed with Chinese characters, to worship and communicate with heaven in order to affirm his divine mandate and reinforce his imperial authority.

Nephrite colors are associated with its two mechanisms of formation: metasomatic replacement of serpentinite (S-type) and metasomatic replacement of dolomite (D-type) (Yui and Kwon, 2002; Harlow and Sorensen, 2005; Liu et al., 2011a,b). S-type is predominantly dark green or green, while D-type is often white, yellow, celadon, or gray (see box A). White nephrite forms exclusively via the metasomatic replacement of dolomite crystals.

The main sources of white nephrite in the Chinese market are China, Russia, and South Korea (Ling et al., 2013). White nephrite from various localities differs in value even if of similar quality. Hence, a method to distinguish the origin of white nephrite is critical in the marketplace as consumers demand this information. Furthermore, origin determination of white nephrite artifacts can be crucial in archaeological provenance studies.

White nephrite from different localities may have very slightly different characteristic appearances. Some experienced collectors and connoisseurs can identify specific sources of nephrite with the unaided eye based on appearance (Wang and Sun, 2013; Chen et al., 2020). As an example, according to Hu et al. (2011) and Wang and Sun (2013), nephrite with a linear “water line” that is more transparent and denser than the adjacent matrix, and that has relatively high overall transparency, typically originates from Qinghai, China. Geochemical methods, including analyzing hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in mineralizing fluids associated with nephrite formation, can also aid in identification of their sources (e.g., Gao et al., 2020; Shih et al., 2024). However, such identification methods may damage the samples and cannot be widely applied.

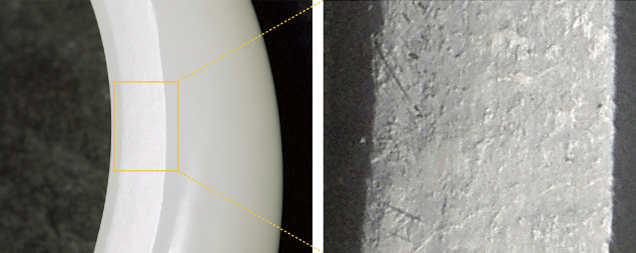

Recently, the authors found an unexpected orange peel effect in Russian white nephrite jade (figures 1 and 2). The effect looks similar to that associated with Burmese jadeite but has its own distinctive pattern. While inspecting white nephrite samples from other localities, we were unable to find this effect on material from outside Russia. After discussing this characteristic with many experienced collectors and dealers and making a broad comparison with microstructures of white nephrite from other localities (e.g., Zhang et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2008; Pei et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2019a; Zhang et al., 2022), we report that to our knowledge, only white nephrite from Russia has this feature. This finding may have significant implications for origin determination of Russian white nephrite jade. This unique microstructure also reveals a distinctive formation mechanism of this gem.

The distinctive ripples and dimple-like surface features on polished jadeite jade are similar to those on the surface of an orange peel or lemon peel. This effect is often a key factor in the separation of jadeite from its imitations or treated equivalents; however, it is rarely mentioned for the identification of nephrite (e.g., Read, 2008; Manutchehr-Danai, 2009; Hansen, 2022). It is assumed that the orange peel effect of jadeite jade is strongly correlated with its microstructure, and specific white and colorless jadeite jades with almost identical chemical compositions and mineral constituents may have varying microstructures (Shi et al., 2009). As white nephrite from various localities differ slightly in appearance, their microstructures may also differ. However, descriptions of microstructure (e.g., felted) in white nephrite are quite similar in the literature (Hou et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2020; Wang and Shi, 2020). Apparently, the differences in white nephrite microstructures have been overlooked.

Given the potential significance of microstructure, the present study was conducted to investigate correlations between microstructures and the orange peel effect in Russian white nephrite, including its impact on appearance, as well as other gemological implications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, white nephrite samples from Russia were provided by a nephrite trading company with the help of Yu Ming at the Chinese Jade Culture Research Center, Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. This company trades with Russian mines and provided 60 white Russian nephrite jade remnants from commercial cutting for this study. Large quantities of raw Russian white nephrite have reportedly been imported from Russia to the Chinese market (approximately 3,500 to 4,000 tons annually between 2019 and 2021; Wang, 2022).

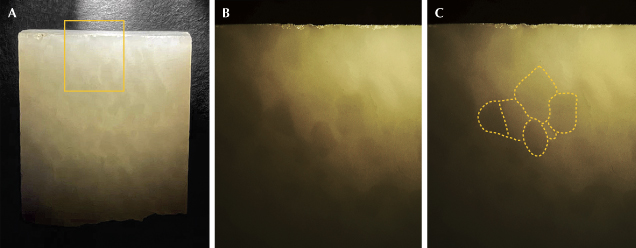

Three representative Russian white nephrite samples (figure 3) were randomly chosen from the 60-piece study set (see appendix 1); all three had a uniform appearance, were translucent and white, and varied slightly in grain size. Standard gemological testing was conducted on the three samples, including examination with a 10× loupe, determination of refractive index and specific gravity (using the hydrostatic method), and observation of the reaction to long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (254 nm) ultraviolet light. Afterward, thin sections for electron probe microanalyses were prepared by cutting a small piece of each sample, gluing them to a glass plate with resin, and then grinding and polishing each sample to a thickness of approximately 70 μm.

Petrographic observations and photomicrographs were obtained with an Olympus BX51 polarizing microscope at the Gemological Center, China University of Geosciences in Beijing (CUGB). Cathodoluminescence (CL) images were acquired with an MK-CL-5200 cathodoluminescence microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi3 microscope camera at the Resources Exploration Laboratory, CUGB, under conditions of 10 s exposure time, gain setting ×20, 250 μA stable current, and 0.003 mbar vacuum.

Backscattered electron (BSE) images and chemical compositions were acquired using a Shimadzu EPMA-1720 electron probe microanalyzer at the Geological Lab Center, CUGB, with a voltage of 15 kV, a beam current of 10 nA, a beam diameter with a spot size of approximately 1–3 μm, and a detection limit for a single element of ±0.01 wt.%. All electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) data processing utilized the ZAF correction method, a standard procedure that accounts for factors affecting the accuracy of elemental analysis: Z (atomic number effect), A (absorption effect), and F (fluorescence effect). The EPMA standards include the following minerals: andradite for silicon and calcium, rutile for titanium, corundum for aluminum, hematite for iron, eskolaite for chromium, rhodonite for manganese, bunsenite for nickel, periclase for magnesium, albite for sodium, K-feldspar for potassium, and barite for barium. The analytical errors for the major oxide content of the minerals were within ±1.5 wt.%, and the formula was calculated according to Shi et al. (2024). The ferric iron contents of the mineral phases were determined using the AX program (Holland, 2009).

The micro X-ray fluorescence (micro-XRF) mapping images were acquired using a Bruker M4 Tornado micro-XRF spectrometer at the National Infrastructure of Mineral, Rock and Fossil Resources for Science and Technology (NIMRF), CUGB, with the tube operating at 50 kV and 300 μA, a pixel size of 20 μm, and a time of 10 ms/pixel. Individual element maps for silicon, calcium, magnesium, aluminum, manganese, sodium, potassium, iron, sulfur, and titanium were detected using the instrument’s software.

RESULTS

Gemological Properties. The standard gemological properties determined for the three Russian white nephrite samples are summarized in table 1.

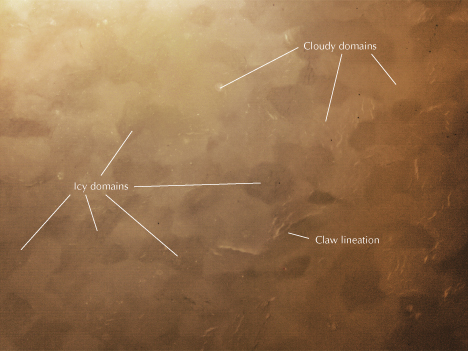

Magnification. Magnification of the polished surfaces of the specimens revealed a mosaic-like granular microstructure. This micro¬structure is characterized by grain-like domains that appear darker under reflected illumination but exhibit greater transparency under transmitted illumination than the lighter granular domains (figure 4). These darker domains resembled ice blocks and thus were referred to as “icy domains.” The other grain-like domains were whiter under reflected illumination and less opaque under transmitted illumination, resembling clouds, and were consequently called “cloudy domains.” Both of these domains form granular pits and bumps on the nephrite’s surface under oblique illumination, similar to a magnified picture of the surface of an orange peel.

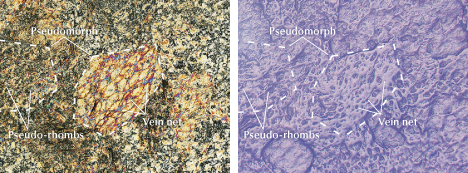

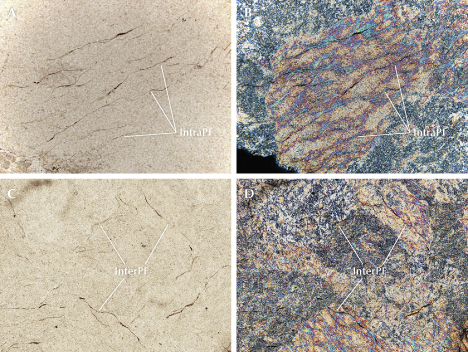

Variations in icy and cloudy domains in the same area of nephrite can be observed when the angle of the incident light changes (figure 5). Each whiter or darker domain appears as an entire grain. Each grain is not a single crystal but is composed of numerous small crystals with sizes less than 2 μm. The whole grain can be regarded as a pseudomorph. With higher magnification, several lenticular contours (figure 6, outlined in red) could be observed within the grains, each with a length not exceeding 700 μm. These lenticular contours may either interconnect to form a network or remain dispersed, constituting a pseudo-rhombic microstructure. In addition, subparallel lineations that together resembled a claw were observed (again, see figure 4).

Chemical Composition. The white nephrite samples studied consist of an almost pure tremolite end member according to EPMA data and Leake et al.’s formula calculations (1997) (figure 7 and table 2). The chemical formula for amphibole is AB2VIC5IVT8O22W2. The meanings of the notations are as follows: A = A-site cations (including Na+, K+, or vacancies); B = large cations in the B-site; T = tetrahedral site cations; C = octahedral site cations; W = anions such as OH–, F–, or Cl– (Leake et. al., 1997).

Due to the presence of hydroxyl groups, the total EPMA content of the amphibole group is usually less than 100 wt.% (e.g., Jiang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Due to the low signal intensity, the chlorine content was not detected. Assuming two hydroxyl groups (2(OH)) for our theoretical calculations, the water (H2O) contents of ELS27, ELS24, ELS13-1, and ELS13-2 were calculated as 2.19, 2.20, 2.19, and 2.20 wt.%, respectively, and the total compositions summed to 99.45, 100.56, 99.89, and 100.15 wt.%, respectively. These deviations were within an acceptable range of ±1.5 wt.% from the ideal 100 wt.% composition.

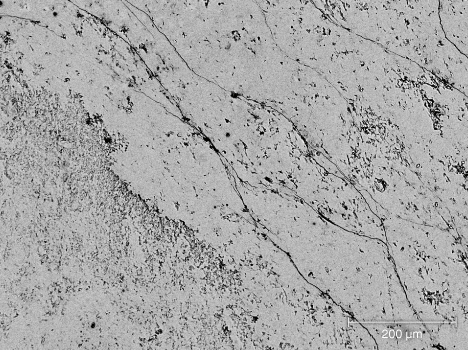

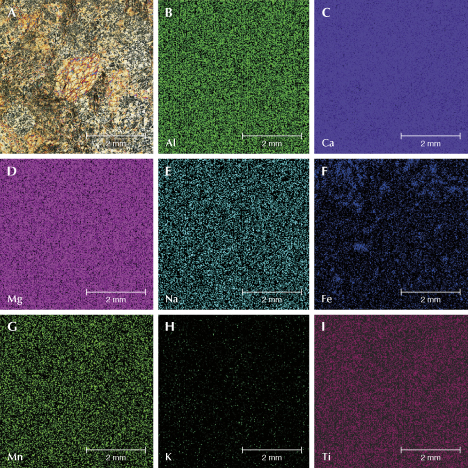

The BSE images of the white nephrite samples were uniform (figure 8), suggesting a nearly homogeneous chemical composition without other apparent mineral components, although minimal calcite and apatite have been reported in Russian white nephrite (Zhang and Zhao, 2012). All the available element map images show nearly homogeneous colors (figure 9), except for the iron map image, in which the darker areas in the intact pseudomorphs indicate richer iron content, whereas the brighter areas in the incomplete pseudomorphs indicate lower iron content, possibly due to slight iron contamination during later-stage growth.

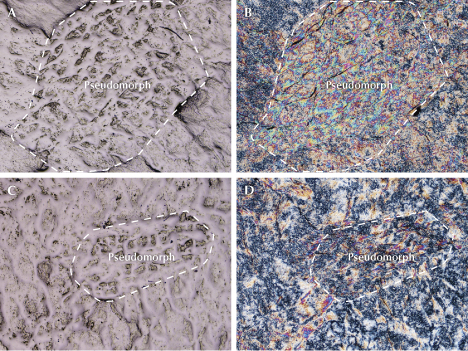

Microstructure. Metasomatic pseudomorph microstructure. Polygonal pseudomorphs were observed in the Russian white nephrite samples (figure 10). They reached 2.0 mm in size and were not single crystals. Instead, each one was an aggregate of many tiny tremolite crystals. Each individual pseudomorph showed flat contact with its neighbors. Together they formed an isogranular mosaic microstructure with respect to the whole nephrite, provided that each pseudomorph was considered a separate grain. This flat contact indicated that the original grain boundaries of the precursor rock were preserved during the metasomatic process. The microstructure exhibited by the pseudomorphs resembles that of a coarse-grained dolomitic marble, which is considered the precursor parent rock. This resemblance suggests that the pseudomorphs formed through metasomatic replacement of dolomite by tremolite. Thus, each pseudomorph was interpreted to be equivalent to a precursor marble crystal from the dolomitic marble parent rock. Notably, the flat contacts between neighboring pseudomorphs were seamless and compact, even under magnification.

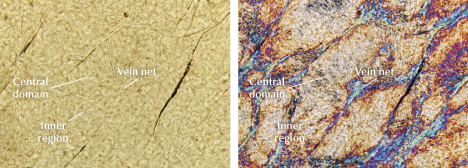

Inside an individual pseudomorph, long and dense tremolite fiber veins form an interconnected network, referred to as the “vein net” (figure 10). The veins intersect and extend across almost one entire pseudomorph, forming connected pseudo-rhombs inside as a result of the replacement of dolomite in the marble by tremolite. Within these veins, tremolite fibers are distributed almost parallel to the vein walls and exhibit nearly identical interference colors and extinction directions. The pseudo-rhombs range from 100 to 500 μm in length and exhibit similar interference colors and extinction directions. Within each pseudo-rhomb is an inner region, mainly composed of fine and compacted fibers, approximately 200 μm in width, and a central domain that may be relatively less compact or even empty (figure 11). The arrangement of these pseudo-rhombs displays a pattern similar to the three typical sets of cleavage planes and twin planes in calcite, dolomite, or both.

The fibers or tiny crystals inside each pseudo-rhomb did not show clear boundaries, and adjacent crystals appeared to be connected. In the central domain, tiny empty spaces often occurred among the tremolite fibers (figure 11). Based on the microstructure, inner region fibers formed under the guidance of the veins. The fibers terminated at the core or reached the other side of the same pseudo-rhomb (figure 11), suggesting a formation sequence of the pseudo-rhomb: from the vein net to the fibrous inner region and then to the central domain. Although the formation sequence was somewhat complicated, the precursor rock had been thoroughly replaced by tremolite, as no carbonate minerals could be detected in the white nephrite studied.

Microstructure Due to Fissures. Two types of fissures exist in the studied samples: intrapseudomorphs and interpseudomorphs (see box A). The former occur within pseudomorphs and mainly developed along the long fiber veins, and some even bifurcated when crossing the intersecting veins (figure 12). In contrast, the latter occur occasionally between pseudomorphs and developed along the pseudomorph boundary. No fissures were observed to cut through a pseudo-rhomb. The fissures ranged from 0.2 to 1.5 mm long. Notably, ductile deformation and dynamic recrystallization dominating the microstructure of jadeite jade from Myanmar (e.g., Shi et al., 2009) were not obvious in the Russian white nephrite due to the flat contacts between the pseudomorphs (figure 10). The direction of the lineation was closely related to its growth microstructure. Some domains in the aggregation were more compact than others (e.g., the centers of some pseudomorphs or some pseudo-rhombs), and microfissures were more likely to occur at the weak edges of these aggregations, forming the intrapseudomorph and interpseudomorph fissures (figure 11). The intrapseudomorph fissures were likely to be the main contributors to claw lineation, which usually occurs on a small scale and is not easily observed without magnification.

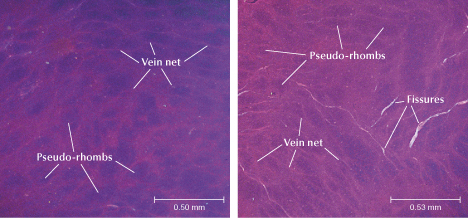

Cathodoluminescence Imaging. CL imaging revealed the presence of vein nets and pseudo-rhombs in the Russian white nephrite. In sample ELS27 (figure 13), the representative vein net exhibits strong pink luminescence, highlighting many pseudo-rhombs with pink to violet light (figure 13). The fissures appeared light pink due to the reflective cathodoluminescence. Notably, figure 13 (right) reveals that the variation in the long-axis directions of the pseudo-rhombs suggests the presence of several pseudomorphs.

DISCUSSION

Microstructure Formation. White nephrite from Russia was reportedly hosted by carbonate rocks and formed through the replacement of dolomitic marble by skarn metasomatism (e.g., Harlow and Sorensen, 2005; Burtseva et al., 2015). Although not all replaced phases have the same microstructure as the precursor rock, the original microstructure was well preserved in the white nephrite studied. The flat boundaries between the large pseudomorphs in the studied nephrite reveal that its precursor rock, dolomitic marble with an isogranular mosaic microstructure, was likely formed by static metasomatism rather than dynamic metamorphism.

Dolomite has three sets of well-developed cleavages, and twin planes easily develop during the diagenetic process. These well-developed planes could have separated and formed pseudo-rhombs inside a single dolomite crystal. Such pseudo-rhombs are similar to the outlines of the vein nets in the pseudomorphs in the studied nephrite. This similarity was interpreted to mean that the vein net outlines were the pseudo-rhomb bodies inherited from the prior dolomite crystal grains. This interpretation is supported by the previously formed parallel vein net that linked the entire pseudomorph, suggesting that an early phase of tremolite precipitation occurred as the fluids penetrated through existing channels induced by the cleavage plane inside the precursor dolomite crystal.

The microstructure of the pseudo-rhombs of the Russian white nephrite showed that the replacement of dolomite by tremolite took place from the rim to the core inside an individual pseudo-rhomb. Since no residual dolomite or calcite was retained inside the pseudo-rhombs and all the reactant products were tremolite without any other phases, the replacement is inferred to be complete, as indicated in reaction 1:

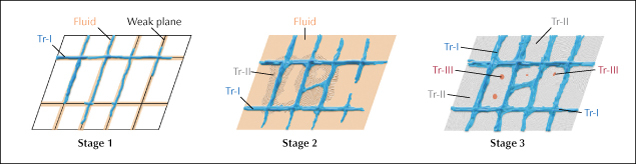

This reaction implied a sufficient fluid supply for metasomatism. Based on the observations, a formation model of Russian white nephrite by fluid flow within a single carbonate crystal (figure 14) is proposed.

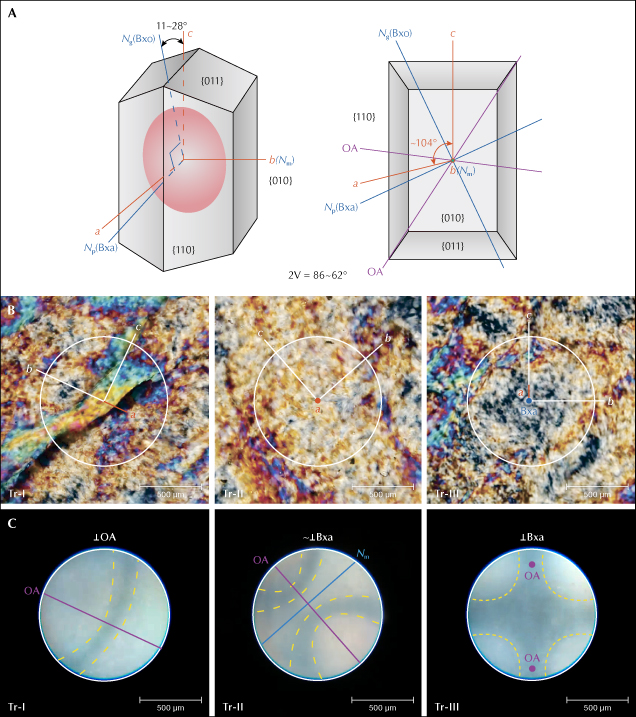

Before metasomatism occurred, transmission channels for fluid flow had already developed through the interconnected planes (i.e., grain boundaries and cleavage planes) in the dolomite of the precursor marble, induced by factors such as abrupt temperature changes or tectonic events. These channels allowed the nascent pseudo-rhombs to be produced. During metasomatism, the fluid then infiltrated along the connected plane net as the carbonate crystals were immersed, and an early-stage tremolite (Tr-I) precipitated by occupying the intersecting plane net, forming the pseudo-rhomb framework of tremolite. This constituted the first formation stage of tremolite and was associated with a precipitation mechanism, as evidenced by the vein nets of the pseudomorph framework having a similar crystallographic orientation (vein net in figures 10 and 11 and Tr-I in figure 14). The initial tremolite framework served to reinforce and emphasize the pseudo-rhombs and was further modified during the metasomatic process. Afterward, middle-stage tremolite (Tr-II) formed through metasomatism and grew from the base of the framework toward the interior of each pseudo-rhomb, as evidenced by the tremolite fibers oriented perpendicular to the outline of each pseudo-rhomb (figure 11, inner region, and figure 14). A late-stage tremolite (Tr-III) formed as tiny fiber-shaped crystal aggregates around the core of an individual pseudo-rhomb, forming a microstructure similar to that of fully encircling agate (e.g., Zhou et al., 2021).

A possible reason for the homogeneous chemical composition of Russian white nephrite is the absence of intermediate phases such as calcite and diopside during metasomatism. Another possible reason is the sufficient fluid supply passing through the pseudo-rhombs, which serve as interconnected fluid pathways and facilitate complete metasomatism, as exemplified by reaction 1.

Pattern of the Orange Peel Effect and Interpretations. Our observations clearly showed that microfeatures among pseudomorphs in the nephrites were distinctive. Within a specific pseudomorph, the separate patterns of the higher-relief vein net and lower-relief central domain observed under reflected illumination correspond directly to the microstructural framework revealed under cross-polarized illumination (figure 15). Moreover, the relief pattern shown in figure 15 (A and C) corresponds to the lenticular contours outlined in figure 6. Possible reasons for the seemingly higher-relief and lower-relief areas on the well-polished surface of the nephrite might involve orientation discrepancies in the tremolite fibers coupled with differences in their refractive indices and dense or less compact configurations. Notably, this visual effect was associated with a relatively flat plane rather than any real topography on the surface (again, see figure 6). The size and shape of the icy and cloudy domains correspond to those of the isogranular mosaic microstructure, with each domain very likely representing one pseudomorph. In figure 5, if the direction of the incident light were changed, then the brightness and transparency of these pseudomorphs may differ. Thus, these differences were associated with the isogranular mosaic microstructure of the precursor dolomite marble before the formation stage of the nephrite.

Microstructural observations of the individual pseudomorphs revealed that the vein net consisted of long tremolite fibers with almost the same orientation distributed along three cleavage planes, forming a three-dimensional network system of pseudo-rhomb frameworks by replacement of a precursor dolomite crystal. A schematic diagram illustrates the approximate orientation of tremolite; conoscopic interference images (featuring characteristic extinction patterns called isogyres) of Tr-I, Tr-II, and Tr-III indicate that the c-axis of tremolite (Tr-I) is subparallel to the cleavage plane of the replaced carbonate (figure 16). According to the optical indicatrix of tremolite (Verkouteren and Wylie, 2000; Deer et al., 2013), the maximum refractive index of tremolite was almost parallel to the long tremolite fiber orientation, and most oblique and vertical fiber sections had greater birefringence. This may explain why the vein net looked higher than the adjacent area. Furthermore, as the pseudo-rhomb may consist of either Tr-II alone or of a combination of Tr-II and Tr-III, the former, consisting of similarly oriented Tr-II, tends to appear relatively flat with minimal light scattering, and the latter, composed of variously oriented Tr-II and Tr-III, develops uneven surface relief that increases light scattering.

The central domain had an indistinct empty space between the tremolite fibers, indicating that the replacement of dolomite by tremolite resulted in volume shrinkage. A calculation based on reaction 1 can reveal the volume change. If the magnesium in dolomite were assumed to be relatively immobile and all the magnesium remained during the replacement of dolomite by tremolite, the volume of ideally calculated tremolite would be ~13% less than that of the replaced dolomite. For a specific pseudo-rhomb, assuming that the vein net framework had been consolidated, the process of forming tremolite would not fully occupy the central domain. This indicates that tremolite formation would require a greater volume of dolomite to be replaced. In this situation, if the earlier tremolite formation resulted in a consolidated framework, such as a vein net, then empty space would consequentially appear, similar to what has been revealed near the central pseudo-rhomb.

Ideally, in the case of individual dolomite grains, when the replacement by tremolite is initiated along the rhomb frame and subsequently formed a framework, the porous interior inside each pseudo-rhomb framework (again, see figures 11B, 13, and 14) could be the consequence of such volume loss to some degree, and a quantity of void space might accommodate further tremolite precipitation, as the precipitation of tremolite occurs widely in both dolomite-replacement and serpentine-replacement nephrites (e.g., Harlow and Sorensen, 2005; Zhang et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2024).

Causes of the Intrapseudomorph and Interpseudomorph Fissures. There are several possible causes for the development of intrapseudomorph and interpseudomorph fissures: volume-reducing replacement, displacement along the weak plane, uneven thermal expansion, or a gradual decrease in formation temperature of the nephrite. The volume-reducing replacement of dolomite by tremolite is regarded as the predominant reason. However, this volume reduction was more or less counteracted by the unique microstructure of the Russian white nephrite. In addition, the replacement occurred at a higher temperature than that during fissure development. This precludes synchronous formation of fissures, as the fissure is assumed to be coeval with the replacement and would have been occupied by precipitation of the fluids. The reason for displacement along the weak plane of the relevant rock and minerals by later tectonic activity, which could have involved carbonate cleavages or mechanical twinning retained during nephritization, the rerupture of veined Tr-III, or deflection along rigid bodies such as pseudomorph boundaries, was proposed by Brown and Macaudiére (1984), Tullis and Yund (1992), and Kushnir et al. (2015). However, flat and undeformed or very slightly deformed boundaries between neighboring pseudomorphs, well-preserved pseudomorphs, and their pseudo-rhombs showed no obvious evidence of this influence. Uneven thermal expansion caused by external forces might have induced fissures. Several Russian nephrite mines are located at elevations between 1000 and 1500 m with seasonal changes involving freezing and thawing, and the anisotropy of thermal expansion in randomly oriented grains might have caused fissures to grow. However, fissures, especially intrapseudomorph fissures, occurred exclusively along the vein of the pseudo-rhombs in the Russian white nephrite samples. Hence, the fissures were considered to be independent of uneven thermal expansion.

The most likely reason for the fissures was a gradual decrease in the formation temperature of the nephrite. For a specific rock body, if its microstructure is homogeneous, then volume shrinkage induced by a temperature drop might occur homogeneously. Some long hexagonal basalt prisms are good examples of this phenomenon (Xu et al., 2020). Although Russian white nephrite is a monomineral aggregate, its microstructure is inhomogeneous, even in an individual pseudomorph. The fissure morphology indicates gradual propagation rather than brittle failure, as evidenced by its selective occurrence along the boundaries among the pseudomorphs and the vein net inside the pseudomorphs. Therefore, such fissure characteristics that correlated with the inhomogeneous microstructure of the Russian white nephrite were interpreted as unique features. Thus, the lineation (especially the claw lineation) in Russian white nephrite has implications for locality identification.

Although lineation similar to that described in this paper has only been found in white nephrite from China (Xinjiang), South Korea, and Russia (e.g., Hou et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2020), the lineation features in Xinjiang and South Korean nephrite show a long, densely oriented pattern or a long, slightly curved pattern and have been subjected to dynamic deformation.

Gemological Implications. Although all white nephrite from Russia, China, and South Korea are hosted by carbonate rocks and formed through the replacement of dolomitic marble (e.g., Yui and Kwon, 2002; Harlow and Sorensen, 2005; Burtseva et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2019b; Zhang et al., 2022), their appearance characteristics (such as transparency, luster, homogeneity, and compactness) are quite similar. However, this study reveals distinctive microfeatures specific to Russian white nephrite.

In particular, among 60 samples of Russian white nephrite, when seven samples with poor transparency and polish were excluded, we determined that 100% exhibited pits and bumps, 88% showed pseudo-rhombic microstructure, 81% displayed icy and cloudy domains, and 68% manifested claw lineation. Compared to the Russian samples studied here, reports from the literature and observations by experienced dealers (e.g., Zhang et al., 2001; Pei et al., 2011) indicate that white nephrite from other localities, including Qinghai, China, and Chuncheon, South Korea, does not exhibit such distinctive pseudomorphs with pseudo-rhombs. Therefore, this pattern of pseudomorphs with pseudo-rhombs in white nephrite from Russia could be regarded as a diagnostic microstructure, and the orange peel effect could be used as a powerful and reliable way to distinguish Russian material from white nephrite originating from other localities, which is possible using only a 10× loupe.

CL imaging revealed the pseudomorphs, veins, and pseudo-rhombs of the Russian white nephrite. The strong pink luminescence of the netlike Tr-I made Tr-II and Tr-III more distinguishable, both of which exhibited pale pink to violet luminescing colors (again, see figure 13). CL imaging strongly supported our proposed model for the formation of this microstructure by fluid flow and precipitation and has further implications for identifying the origin and understanding the details of the formation of Russian white nephrite. The distinct CL characteristics of distribution, color, and intensity observed between Tr-I and Tr-II + Tr-III imply variations in their formative fluid properties or other growth conditions.

This microstructure, as well as the appearance of the orange peel effect on the polished surface of Russian white nephrite, has significant implications for understanding this nephrite’s special properties and usage. The fissures and central domains within the pseudo-rhombs indicate that the nephrite material might easily become colored naturally in the presence of various dissolved metal oxides, which could explain a feature that Russian white nephrite often has: a thick “skin” with color variation. Such skin makes the white nephrite highly desirable for expressive carvings (e.g., Wang and Shi, 2020; figure 17). The thick colored layer may have geological and gemological implications that need further investigation to fully understand. Conversely, this characteristic may also allow this material to be deliberately dyed in the laboratory or factory, potentially causing problems with its identification.

CONCLUSIONS

White nephrite from Russia has a distinctive orange peel effect and a fissure-like surface, both of which can be attributed to a well-preserved isogranular pseudomorph microstructure formed through a unique metasomatic process. This microstructure features a three-dimensional net pattern that reflects its specific formation conditions.

A distinctive three-stage metasomatism model of dolomite replacement by tremolite for this Russian white nephrite with a unique microstructure of individual pseudomorphs was proposed. In the early stage, the Tr-I veins precipitated out during fluid flow, establishing a vein net for the pseudo-rhombs. In the middle stage, Tr-II formed on the foundation of the vein net, growing toward the inner domains inside the pseudo-rhombs. Finally, in the later stage, the Tr-III possibly filled the central parts of the pseudo-rhombs (the less compact parts of the domains). These complicated and independent pseudomorphs together create the distinctive microstructure of the Russian white nephrite.

The results of this study will contribute to not only understanding the microstructure of Russian white nephrite, but also to supporting the origin traceability of white nephrite.

.jpg)