Exhibition Review: Mogul to Modern: Met Exhibit Showcases Indian Jewels

November 13, 2014

India’s jewels have inspired collectors around the world ever since.

One of the most noted connoisseurs, Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al-Thani of Qatar, recently selected 60 pieces from his private collection of Indian gems and jewelry—one of the world’s largest—for display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Treasures from India: Jewels from the Al-Thani Collection” opened Oct. 28 and will run through Jan. 25, 2015.

In the Indian tradition, gemstones served a purpose well beyond adornment and display of wealth, according to Dr. Amin Jaffer, Christie’s international director of Asian art. Jaffer presented a lecture at the Met on “The Role of Jewels in Projecting Power in Royal India” the day after the exhibit’s opening.

Dr. Amin Jaffer, Christie’s international director of Asian art, presented a lecture at the Met on Indian royalty’s use of jewelry. Photo by Russell Shor.

“Jewels were highly symbolic of royal power,” Jaffir said, noting the great many paintings over the centuries of Indian rulers laden with gemstones. “Diamonds above all projected power, as they are hard stones and so associated with invincibility,” he said, adding that the majority of the wearers were men.

“His Highness the Maharajah of Indore” was painted by British artist George Landseer in

1861. Courtesy of Amir Mohtashemi Ltd., London.

The jewels on exhibit at the Met range from the dawn of the Mogul period in the mid-17th century to contemporary designs that incorporate both Indian and Western elements. The exhibit demonstrates how Indian fashion and design evolved through contact with European jewelers.1861. Courtesy of Amir Mohtashemi Ltd., London.

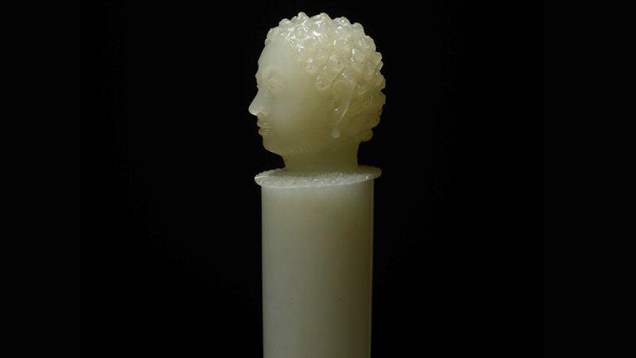

Among the exhibit’s earliest pieces is a dagger hilt from the early Mogul period, about 1620, of white nephrite jade intricately carved in the shape of a head. The European influence is evident in the carving’s similarity to a Portuguese Goan image of Christ as the Good Shepherd.

This nephrite jade dagger hilt, circa 1620–1625, demonstrates a European influence through its similarity to a Portuguese Goan image of Christ. Courtesy of Servette Overseas Ltd. and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Emeralds became an integral part of Indian royal jewels in the 16th century after the discovery of deposits in Colombia. A gold tiger’s-head finial (an ornament atop a staff or frame) from about 1790 inlaid with diamonds and rubies and draped with an emerald collar was one of eight such figures that adorned the throne of Tipu Sultan, known as the Tiger of Mysore. The throne was dismantled in 1799 after the sultan was killed following a battle.

This tiger’s-head finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan, circa 1790, features gold inlaid with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. Courtesy of Servette Overseas Ltd. and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Head ornaments, mainly for the front of turbans (jigha) and head bands (sarpesh) are a major part of the exhibition. One of the most stunning examples is the sarpesh shown in the lead photo. Measuring approximately 11 inches long, it is set with polki diamonds (still in their original rough forms but with the faces polished) and 10 large spinels suspended from the gold mounting. Although the piece was made between 1875 and 1900, the spinels are from a much earlier date. Like most traditional Indian jewels, the back is enameled.India comprised more than 500 semi-autonomous states at the beginning of British rule in 1858. The jewels grew in extravagance after the British assumed control, and much of the wealth and power of the Moguls shifted to local rulers who no longer competed for military might but to see who could amass the most jewels.

“Rulers began making European-style crowns and tiaras, many of them extremely elaborate,” Jaffer said. Since India’s gem mines had long dried up by then, gems were extracted from centuries-old pieces. One ruler, the Maharaja of Patiala, gave Cartier and Boucheron more than 100 major gemstones to remount into modern jewels.

“It is still the largest single consignment that the jewelry house has ever had,” Jaffer said.

Indeed, by the latter part of the 19th century, jewelers such as Cartier regularly traveled to India to serve the princes who ruled under British control. These jewelers brought with them new styles and techniques, and the Indian royals often had some of their most prized jewels reset into modern pieces that reflected both cultures.

One Mogul-era carved emerald was reset into a platinum aigrette (head plume), topped with a sapphire and pearl spray, by French designer Paul Iribe around 1910. Unlike most pieces in the collection, this was an Indian-inspired piece created for a European wearer.

French designer Paul Iribe’s aigrette, circa 1910, has a Mogul-era carved emerald set in platinum with a plume of diamonds and sapphire and pearl beads. Courtesy of Servette Overseas Ltd. and the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The tradition of blending Indian and Western design elements around large gemstones continues today and is well featured in the exhibit. Contemporary jewelry designer JAR (Joel Arthur Rosenthal) created a brooch in 2002 in the form of a cusped-arch window of the Jaipur Pink Palace, setting a 35.36 carat octagon-cut emerald inside and backing the gem with white rock crystal. And in 2010, the Jaipuri-born designer Santi Chaudhary created a ring with a 31 carat Mogul-era carved emerald bead set high on prongs to allow it to revolve.According to an Indian proverb, “The value of a gem can only be realized by a king or jeweler because only they understand their complexity.” Today, gemologists have an understanding of gemstones far beyond that of the ancient royals, but their tradition of weaving jewelry into all parts of life remains strong.

About the Author

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad, California.

.jpg)