The Primary Sapphire Occurrence at French Bar Sill Along the Missouri River, Near Helena, Montana

ABSTRACT

Sapphires have been mined in Montana since being discovered at Eldorado Bar, along the Missouri River, in 1865. The most valuable gold deposit in the area was mined near the top of the French Bar complex from 1867 to 1869. On portions of the Virginia terrace and the Center terrace, the French Bar sill, which sparsely contained sapphires in a host rock—identified here as a basaltic trachyandesite, but described elsewhere as a minette—was reported by Kunz in 1891. Other than Yogo Gulch, where the sapphires are in a lamprophyre dike, the French Bar sill is Montana’s only other source of gem-quality in situ sapphire. New ownership of the property in 2020 has resulted in the largest production to date, although it is still sparse. In this study, the authors examined 80 French Bar sill sapphires in matrix; 16 sapphires removed from the matrix, ranging from very small to 17.99 ct; 4 faceted stones; and 5 partly polished crystals. Trace element chemistry and inclusions were consistent with—and generally indistinguishable from—faceted Montana sapphires from the secondary deposits of the Missouri River, Rock Creek, and Dry Cottonwood Creek. This indicates that while the magmatic material (Eocene volcanism) that transported the sapphires from deep within the earth was different in certain cases, such as with French Bar sill, the genesis of the sapphires may be the same or similar. Many of the surface resorption features are similar, but one important distinction exists. Around 25% of Missouri River alluvial sapphires have encrustations of spinel, likely a result of reaction during transport by a mafic magma. Primary French Bar sill sapphires always have an encrustation of biotite (phlogopite) mica, but never spinel. The French Bar sill itself is certainly too small in extent to have supplied all the alluvial sapphires found at the Missouri River.

In the gemological literature, Yogo Gulch is the only well-documented primary occurrence of gem-quality sapphire in Montana, although French Bar—the only other in situ deposit of gem-quality sapphire, also in igneous rock (figure 1)—has been occasionally mentioned throughout the decades, beginning with Kunz in 1891. However, three in situ deposits of non-gemmy (opaque) corundum in the Precambrian metamorphic rocks of southwestern Montana have been described by Clabaugh (1952): Elk Creek, Bozeman, and Bear Trap. All three are located southwest of Bozeman.

A recent rediscovery in 2020 and expanded excavation at the French Bar sill shed new light on this lesser-known deposit. Significant direct excavation of the sill began to produce an increased number of larger sapphire-in-matrix specimens. It has been 135 years since the discovery of the French Bar sill, and with many larger in situ sapphires recently recovered, there has been an opportunity to extensively research this material. Many of those results are presented in this article.

In 2020, Kale and Sharlene Wetherell purchased 107 acres of property containing the French Bar sill. In late 2023, Kale Wetherell provided author KP, an expert gem cutter specializing in Montana sapphire who has had the privilege of working with some of the world’s rarest and most exceptional sapphires, with several photographs of sapphires in matrix from the French Bar sill locality. One of these specimens contained an 11.15 ct sapphire crystal, which was later faceted by author KP into a 3.49 ct sapphire (figure 2). Though specimens of such remarkable size and quality have been recovered, French Bar has remained a secret among gem enthusiasts. As more sapphires in matrix were recovered and documented from this location, author KP shared the find with the coauthors of this paper. This discovery has significant implications for the understanding of sapphire deposits in Montana and warrants further research and documentation.

HISTORY

Kunz (1891, 1893, and 1897) was the first gem and mineral expert to describe the primary (in situ) occurrence of Montana sapphire in an andesite dike. In 1891, a Helena newspaper also reported sapphire in matrix at French Bar (Daily Independent, 1891). Today we recognize the French Bar sapphire occurrence as a sill. Dikes and sills form similarly; dikes cut vertically through rock layers, and sills are tabular (horizontal) intrusions. Kunz (1890) initially described the host rock as “trachyte rock” and then as an “andesite” in subsequent publications. Today we recognize it as a basaltic trachyandesite (Berg and Palke, 2016; Berg, 2018), which is a rock with a composition between trachyte and andesite.

In 1906, Pratt offered a very good description of the French Bar sill based upon his own visit to the Montana deposit as well as Kunz’s work. Pratt described two occurrences of corundum-bearing dikes of andesite (the one he visited at French Bar and the one Kunz described as a sapphire-in-andesite occurrence, known as “Ruby Bar”). He concluded that “it is possible that the bar described by Kunz is the same one known as French Bar.” Clabaugh (1952) agreed with these sentiments.

Over the last 135 years, the literature has included conflicting reports about the number of different locations of sapphire-bearing dikes along the Missouri River. Many writers identified two different ones, and Mertie et al. (1951) mentioned three localities. The current authors’ exploration of the area, as well as Berg and Landry’s (2018) historical analysis, suggest that there is likely only one sapphire-bearing area of the sill on the southern side of the Missouri River.

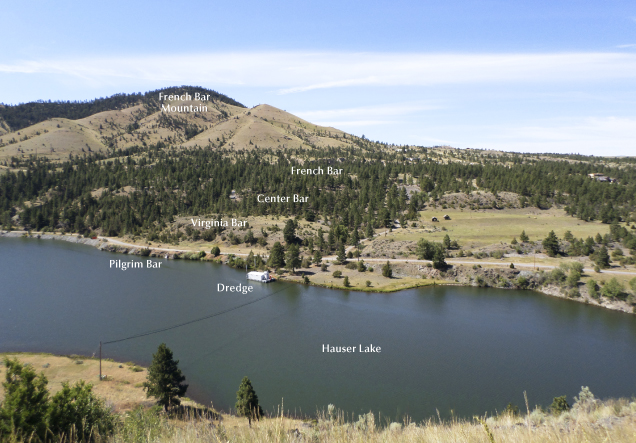

Among miners and geologists and in the literature, this area is often referred to collectively as French Bar. However, Raymond (1870) noted that at the lower portion of French Bar Mountain are four terraces or plateaus (today’s vernacular calls them “bars” because they are gravel bars, or more precisely “strath terraces”), one adjacent to another. Pilgrim Bar begins at the river (today it is partially submerged under Hauser Lake) and continues uphill through Virginia Bar, followed by Center Bar, and then the largest area, French Bar, at the top (figure 3). The approximate elevations are: Pilgrim Bar at 1,121 m; Virginia Bar at 1,122 m; Center Bar at 1,144 m; and French Bar at 1,168 m.

According to Pardee and Schrader (1933), the strath terrace known as “French Bar” was the richest and most extensively mined of the river terraces among the various gold fields of the Missouri River near Helena during the 1860s (figure 4). The French Bar hydraulic mining pits were collectively more than 1.60 km in length and ranged from 15 to 123 m wide, totaling around 125 square meters (150,000 square yards). They were estimated to have yielded $10 of gold per yard, for a total of $1.5 million (Lyden, 1948)—a considerable sum of money for 1933.

Pardee and Schrader (1933), as well as the various subsequent authors writing about French Bar (e.g., Kunz, 1897; Pratt, 1906; and Clabaugh, 1952) did not mention sapphires being found among the extensive dredging of French Bar from 1867 to 1869. It is possible that the French Bar hydraulic gold miners did recover small amounts of secondary sapphires and, like other gold miners along the Missouri River, discarded them due to lack of interest.

Kunz (1893) reported “…no doubt that all of the sapphire along these bars of the Missouri is derived from the breaking down, by glacial action, of a rock similar to this. The outcrop at the Ruby Bar cannot, however, account for the deposit of sapphires at Eldorado Bar, 6 miles to the north; and it will be necessary to await further discoveries before attempting to determine the exact source of these gems.”

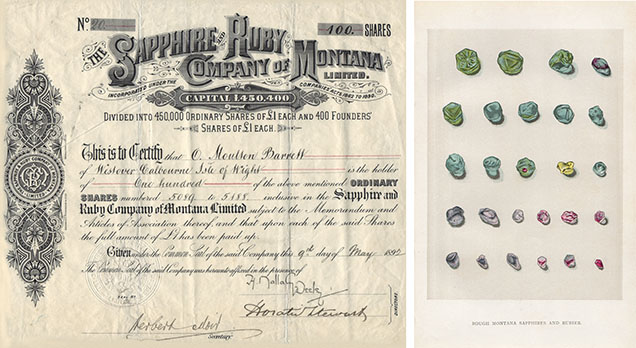

The Spratt brothers obtained an option in late 1889 to purchase Ruby Bar, located on the eastern end of French Bar. In 1890, the Sapphire and Ruby Company of Montana Limited, an English syndicate company partly owned by well-known gem dealer, author, and jeweler Edwin Streeter, entered into a contract to purchase the Ruby Bar (known today as French Bar) and Eldorado Bar properties (Streeter, 1892) (figure 5). The purchased property included nearly all 7,000 acres of the sapphire-bearing property, extending along the Missouri River for approximately 24 km. Streeter’s company owned French Bar for a short time but never commercially mined it for gold or sapphire. The 1897 ownership liquidation of the properties went back to Augustus N. Spratt and was reorganized as the Montana Gold and Gem Company.

Mertie et al. (1951) stated that Streeter’s company “drove several tunnels wherein one or more sapphire-bearing dikes were discovered. These tunnels are now submerged by the water of Hauser Dam, but in one of these dikes, visible at the surface, crystals of sapphire occur sparingly.”

In 2025, Crystel Thompson discovered what appears to be a new extension of the French Bar sill across a reservoir portion of the Missouri River (Hauser Lake), located 0.12 km from the shore near the campground in a north-northeast direction. This new area is also across the river and north-northeast of the abovementioned “sapphire-bearing dikes” (now underwater) discovered in the 1890s (Mertie et al., 1951), and approximately 0.5 km from the 1891 sill described in this article. This newly discovered sill contains primary sapphires in matrix. Numerous sapphire crystals have been recovered thus far, including one larger than 11 ct that was faceted into a 4.01 ct gem, which exhibits a strong color change from medium blue to blue-violet. In this new area, sapphires in matrix have adhering biotite (phlogopite). Not only do the rocks containing these sapphires visually match the appearance of the basaltic trachyandesite from the other side of the river, but data from the whole rock chemical analyses plotted in a total alkali silica (TAS) diagram (to be published separately) confirm this. Mapping and further research will be necessary to establish whether this is an extension of the sill first mentioned by Kunz in 1891 and discussed throughout this article.

LOCATION AND ACCESS

The primary French Bar sill is located in Lewis and Clark County, 21 km northeast of the Helena airport. It is situated at the eastern end of the seven historical secondary sapphire-bearing gravel bars, which are spread out among the approximately 22 km length between Canyon Ferry Dam and Hauser Dam (figures 6 and 7).

The French Bar complex contains four named bars, or strath terraces: Pilgrim, Virginia, Center, and French, which is the largest and highest. Pilgrim is 0.61 km from Canyon Ferry Dam, beginning underwater in Hauser Lake and continuing steeply uphill southwest to the historic 1867–1869 hydraulic gold mining area named French Bar (again, see figure 3). The sapphire-bearing French Bar sill is currently poorly exposed and lies partially on Center terrace and Virginia terrace. The area is accessible from Helena by car, or by boat directly across the lake from the Riverside Campground and boat launch.

DESCRIPTION OF FRENCH BAR SILL AND SAPPHIRES FOUND IN SITU

General Description of the French Bar Sill. The sapphire-bearing French Bar sill (figure 8) is poorly exposed between French Bar and Hauser Lake (partially on Center Bar and Virginia Bar) for a length of less than 98 m and is 1–2 m thick, as reported by Berg and Dahy (2002) and Berg and Landry (2018). Pratt (1906) noted that the compass bearing of a horizontal line within the dike’s plane is N 5° to 10° E, and it dips 45° E. This exposure is around 53 m south of the lake’s shore.

Sapphires in a primary (hard rock) deposit are more difficult to recover, and fewer are present per cubic meter of earth than in secondary mining. As a result, at this time the deposit is more of a curiosity and lacks the potential to become a profitable and productive sapphire mine. Although the French Bar sill mine could become an important source of Montana sapphire-in-matrix mineral specimens, its greatest value is from a scientific point of view because it provides clues to understanding the genesis of Montana’s sapphires.

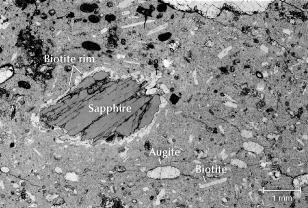

General Description of the French Bar Sill Rock. The French Bar sill is composed of sparse biotite (phlogopite)1 and augite phenocrysts set in a partly altered groundmass of plagioclase microlites and biotite (phlogopite) autoliths as well as apparent volcanic glass (Berg and Palke, 2016). Berg and Dahy (2002) and Berg and Palke (2016) also described xenocrysts of garnet, quartz, and corundum as well as xenoliths composed of calcic plagioclase, amphibole, garnet, margarite, and spinel, occasionally containing corundum. When found, corundum xenocrysts have a rind of biotite (phlogopite) mica and a thin inner layer of clay (Berg and Palke, 2016) (see Mining Techniques section, as well as discussion below).

1As described later in this manuscript, previous works used the name biotite for the dark mica found in the French Bar sill and adhering to its sapphires. Using chemical analysis, this work has determined the dark mica to be phlogopite, the magnesium-dominant end member of the biotite group. However, acknowledging the ubiquitous use of biotite in related works, the name is used here as well in addition to its proper mineral name, phlogopite.

Previous authors have described the French Bar sill rock as either a basaltic trachyandesite (Berg and Palke, 2016) using the TAS diagram of LeBas et al. (1986) or as an evolved minette, a type of lamprophyre (Irving and Hearn, 2003; Prelević et al., 2004). The distinction between these two classification schemes is that one is based on a petrogenetic classification that estimates the abundance of constituent minerals in the rock (minette), while the other is based on chemical classification (basaltic trachyandesite). In fine-grained rocks in which the abundance of constituent minerals cannot be estimated, a chemical classification based on the TAS compositions is a more suitable naming scheme. Given that the French Bar sill rocks consist of fine-grained mineral textures showing predominantly glass and few phenocrysts, these rocks are better described using the TAS diagram for volcanic rocks, suggesting the appropriate term is basaltic trachyandesite (figure 9 and table 1).

Table 1 shows the major element composition of these rocks (a description of the data collection is in the Methods section). The loss on ignition (LOI), which represents the water taken up in the rock or in hydrous minerals, was from 9.29 to 14.75 wt.%. This relatively high LOI indicates that the overall composition may have been altered to some extent by weathering at the surface, which is also consistent with the relatively high calcium oxide content, suggesting the possible presence of secondary carbonate minerals. Berg and Palke (2016) came to a similar conclusion.

However, with everything taken into consideration, this discussion becomes somewhat academic. For instance, Prelević et al. (2004) plotted the whole rock geochemistry of a rock classified as a minette on a TAS diagram where it plotted in the basaltic trachyandesite and trachyandesite fields (again, see figure 9). The possible similarity in chemistry between these two rock types indicates that they likely have a similar genetic origin even if they have differences in petrographic textures. Also, Rock (1991) has pointed out that classification of lamprophyres is exceedingly difficult, using the example of the Arrow Peak dike in Montana, wherein the ultramafic rock was classified as five different rock types by five different authors.

MINING TECHNIQUES

Sapphire-in-matrix specimens are collected using simple hand tools, such as rock hammers, pry bars, and chisels. Occasionally a small excavator has been used to remove overburden to widen the exposure of the basaltic trachyandesite hard rock sill. Only a few loose sapphires have been found in the soil surrounding an area where the sill is weathering (breaking apart).

Once a smaller piece of rock has been removed from the sill, liberating the sapphires is done by further breaking down the basaltic trachyandesite matrix with a hammer and chisel. If a sapphire is present in the piece being hammered, the rock often breaks along the sapphire’s edge, with the sapphire protruding out in one piece of the broken matrix, leaving the other portion with a concave impression covered in a thicker layer of biotite (phlogopite) crystals over a very thin layer of clay (figure 10). If the piece containing a sapphire will be preserved as a mineral specimen, dental tools and/or a small abrasive air gun are used to neatly remove some of the matrix surrounding the sapphire to create an attractive appearance (figure 11).

Traditionally used for medical imaging, X-ray computed microtomography is now widely used on geological and gemological material, for example, identifying some natural and cultured pearls. Korbin and Peterson (2018) used an X-ray computed tomography (CT) scan to reveal previously hidden Yogo Gulch sapphires entirely within the lamprophyre rock matrix. Similarly, in this study, CT was used experimentally on several French Bar sill matrix samples to identify the presence of sapphire crystals inside the rock.

All of the remaining pieces of basaltic trachyandesite matrix without visible sapphires at the surface undergo a tumbling process in which they are put into a cement mixer with a small amount of water. After a few days, the matrix is nearly all broken down, leaving a surprising number of sapphires.

THE PRIMARY FRENCH BAR SILL AND POSSIBLE BEDROCK SOURCES FOR THE SECONDARY MISSOURI RIVER DEPOSITS

As mentioned above, some early reports described the French Bar intrusive body as a dike, but it is more accurately described as a sill that was emplaced in near-horizontal metasedimentary beds of the Mesoproterozoic Belt Supergroup. The earliest published reference to this sapphire occurrence was by Kunz in 1890. The sill is 1–2 m thick and exposed for a length of 98 m when examined in a shallow excavation made more than 50 years ago. More recent excavation has exposed a greater length of the sill.

Sapphires have been found in only one bedrock occurrence in this area, a small sill at French Bar along Hauser Lake. As mentioned above, however, another area has sapphires in situ in rock outcrops. These rocks were recently identified as basaltic trachyandesite. It appears to be a continuation of the French Bar sill across the river, but future research and mapping are necessary. The French Bar sapphire-bearing sill has a low concentration of corundum and is clearly not the source of most of the sapphires in the Hauser Lake deposits. This unique occurrence could provide insight into other bedrock sources of sapphires in the area.

Magma forming the French Bar sill intruded metasedimentary rocks of the Precambrian Belt Supergroup during the Eocene as determined by an argon-argon plateau age of 49.5 ± 0.1 Ma (Irving and Hearn, 2003), which is very close to the age of the Yogo sapphire-bearing dike in central Montana. The sill is poorly exposed near the south shore of Hauser Lake between Virginia Bar and Center Bar, two of the four strath terraces identified at this locality. Although several dikes are exposed on the west slope of French Bar Mountain, sapphires have not been found in any besides the one in this study.

The most direct method of determining the bedrock source for an alluvial sapphire deposit is to identify sapphire in bedrock. Because of sapphire’s durability and density, it can be concentrated in alluvium where there is no apparent bedrock source. This is the case for sapphires at the Missouri River, Rock Creek, and Dry Cottonwood Creek deposits, where all of the original volcanic transport rock (i.e., the matrix) has been completely weathered away.

Berg and Landry (2018) stated that the following considerations aid in limiting the possible bedrock sources of sapphires mined along the Missouri River in this area:

- The majority of the Missouri River sapphires—from Canyon Ferry Dam to Hauser Lake Dam—do not show significant evidence of abrasion, suggesting relatively short river transport.

- Sapphire occurrences such as McCune Bar, Metropolitan Bar, and Gruell’s Bar occur at significantly higher elevations and are restricted to the east side of Hauser Lake.

- The previous hypothesis that Missouri River sapphires might have formed where intrusive igneous rocks had metamorphosed local aluminous sedimentary rocks is unlikely due to a lack of sapphire occurrences in the Spokane Hills on the east side of Canyon Ferry Lake.

- The surfaces of approximately 25% of the sapphires from the Missouri River deposits are partially coated with spinel. This implies that the magma that transported these sapphires contained significant magnesium and that the surface-coating spinel formed as a result of the magnesium reacting with the sapphires.

Occasionally sapphire crystals with rounded and smooth surfaces have been found, which is visibly different from the irregular surfaces of typical sapphires from these bars. This may indicate that these sapphires were abraded as they were transported over a long period along the river. This could indicate a possibility that some sapphires in the Missouri River bars came from distant upriver sources. However, the absence of significant sapphire deposits in more distant locales suggests a more local source for the Missouri River sapphires.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples. For this study, 80 matrix specimens, 16 loose sapphire crystals (removed from the matrix), 4 faceted stones, and 5 partly polished loose sapphire crystals were examined. All samples were from the primary French Bar sill. To locate sapphire phenocrysts, 40 kg of French Bar sill rock was sawn (slabbed) and turned into more than 150 glass-backed “thick sections” approximately 100 μm thick. (Thin sections are typically ground and polished to only 30 μm thick.) These petrographic thick sections were used by author RB in his research on the sill and then donated to GIA for inclusion in their research collection. All samples exhibited natural colors and were not heat treated. On a few samples, remnants of adhering dike rock, including biotite (phlogopite), were removed by placing the specimens in hydrofluoric acid for several days. Unless stated otherwise, all instrumental analyses described here were performed at the GIA laboratory in Carlsbad, California. The bulk of the samples were collected by Kale Wetherell during the last four years. Some of the samples were recovered by the authors during on-site exploration at the mine in June 2024. Additional samples came from the collections of authors RK, RB, and RT, as well as Crystel Thompson. All materials studied were given sample identifiers including initials and a number.

Standard Gemological Examination. Routine gemological testing was performed using standard techniques and equipment in Helena, Montana, and at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology at Montana Tech of the University of Montana. These included standard gemological instruments used to measure refractive index, birefringence, specific gravity, and pleochroism. Microscopic observation was performed using a GIA/Leica gemological binocular digital microscope, a Dolan-Jenner 150-watt Fiber-Lite, and a Leica M165C microscope.

Photomicrographs. Photomicrographs were taken at both GIA in Carlsbad and AGL. Either a Nikon Eclipse LV100 compound microscope or a Nikon SMZ1500 binocular microscope outfitted with a Nikon DS-Ri2 camera was used for recording images. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were taken on the LV100. Also used was a Nikon SMZ25 stereo microscope equipped with dual fiber-optic illuminators, darkfield and brightfield illumination, polarizing filters, and a Nikon DS-Ri2 camera.

Whole Rock Geochemistry. Whole rock geochemistry analysis was carried out during this study at Actlabs in Ancaster, Ontario, Canada, using lithium metaborate/tetraborate fusion and inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using 14 prepared USGS- and CANMET-certified reference materials. Details of this analysis can be found under the 4B and 4B2-STD sections: https://actlabs.com/geochemistry/lithogeochemistry-and-whole-rock-analysis/lithogeochemistry/. The processed data from this work is presented in table 1 and is plotted in a TAS diagram in figure 9.

Ultraviolet/Visible/Near-Infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) Spectroscopy. Non-polarized spectra were collected with a GIA UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer, constructed from an AvaSphere-50 integrating sphere, an AvaLight-DS deuterium light source, and a QE Pro high-performance spectrometer. Polarized UV-Vis-NIR spectra were collected at American Gemological Laboratories (AGL) in New York, with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 950 spectrophotometer.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy. FTIR spectra were collected at GIA in Carlsbad and AGL using a Thermo Fisher Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer equipped with an XT-KBr beam splitter and a mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector operating with a 4× beam condenser accessory. The resolution for this data collection was set at 4 cm–1 with 1.928 cm–1 data spacing.

Raman Spectroscopy. Inclusions were identified, when possible, using Raman spectroscopy at AGL with a Renishaw InVia RM1000 micro-Raman spectrometer equipped with 514 nm argon-ion laser excitation. In many cases, the confocal capabilities of the Raman system allowed inclusions beneath the surface to be analyzed.

Laser Ablation–Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). Trace element chemistry was collected by LA-ICP-MS using a Thermo Fisher iCAP Qc ICP-MS, coupled to an Elemental Scientific Lasers NWR 213 laser ablation system with a frequency-quintupled Nd:YAG laser (213 nm wavelength with 4 ns pulse width). Ablation was carried out with 55 μm spot sizes, with a fluence of 8–10 J/cm2 and a repetition rate of 20 Hz. The isotope 27Al was used as an internal standard at 529250 ppmw, and synthetic and natural corundum reference materials were used as external standards (Stone-Sundberg et al., 2017). Detection limits ranged from 0.02 to 0.06 ppma for magnesium, 0.05 to 0.27 ppma for titanium, 0.005 to 0.006 ppma for vanadium, 0.09 to 0.34 ppma for chromium, 1.2 to 14 ppma for iron, and 0.003 to 0.004 ppma for gallium. Trace element values are reported here in parts per million on an atomic basis rather than the more typical parts per million by weight basis used for trace elements in many geochemical studies. Units of ppma are the standard used in GIA laboratories for corundum, as they allow a simpler analysis of crystal chemical properties and an understanding of the color mechanisms of sapphire and ruby. Conversion factors were determined by a simple formula that can be found in table 1 of Emmett et al. (2003).

Petrographic, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) Analyses. The prepared thick sections were studied with a binocular petrographic microscope by author RB at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology at Montana Tech of the University of Montana. Some SEM images were recorded using a JEOL 6100 scanning electron microscope in the Image and Chemical Analysis Laboratory in the Department of Physics at Montana State University. Most specimens were coated with gold-palladium and a few with iridium. Other SEM work including backscattered electron (BSE) imaging and chemical measurements by EDS were carried out with 15 kV accelerating voltage on a Zeiss EVO MA10 scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford X-Max^N EDS detector. BSE images were stitched together using the method described by Preibisch et al. (2009).

Photoluminescence (PL) Mapping. Photoluminescence maps of Cr3+ fluorescence of the sapphires were collected on a Thermo Scientific DXRxi Raman imaging microscope with a 633 nm laser excitation wavelength. Count times varied from 0.033 to 0.167 s exposure time and 0.1 to 1.5 mW power. The PL maps display changes in the area of the ~694 nm PL band to reveal growth zoning patterns related to differences in chromium concentrations throughout the table of each faceted sapphire’s surface. This is displayed as a false-color image showing maximum peak areas in red and minimum in blue.

Oxygen Isotope Analysis. Oxygen isotope ratios were collected from sapphires on a CAMECA IMS 1280 secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) in the WiscSIMS lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The sapphires from which data are reported in this study were extracted from five French Bar sill matrix samples (collected on-site by authors RT and RB in 2019) by dissolution with hydrofluoric acid and were then mounted into an epoxy puck for analysis by SIMS. Only four of the five matrix samples contained sapphires. One rock contained four of the tested sapphire crystals (samples 19FB1-1-1, 19FB1-1-2, 19FB1-1-3, and 19FB1-1-4), and the other three rocks contained one crystal each (samples 19FB1-2-1, 19FB1-3-1, and 19FB1-5-1). All samples were mounted in epoxy. Details of oxygen isotope methodology are provided in Turnier et al. (2024).

GEMOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF FRENCH BAR SILL PRIMARY SAPPHIRE

Standard Gemological Properties. In general, all gem sapphires from different geological deposits share the same or overlapping values (depending upon color and trace element chemistry) for specific gravity, refractive index and birefringence, exposure to long-wave and short-wave ultraviolet radiation, and pleochroism, and thus do not have significant differences. The French Bar sill sapphires were verified to have measured values and reactions that were standard for sapphire. However, trace element chemistry and the full inclusion suite (including color zoning) can often distinguish secondary Montana sapphires—and French Bar sill sapphires—from those produced in other areas around the world. While groups (lots) of rough crystals from the three Montana secondary deposits can often be distinguished from one another based on their surface features, once they are faceted, they often cannot be reliably differentiated.

Based on examinations of the inclusions, spectra (UV-Vis-NIR and FTIR), trace element chemistry, and oxygen isotope analysis of French Bar sill sapphires—as discussed in the following sections—the characteristics of these sapphires overlap to a large extent with the secondary sapphires at the Missouri River, Rock Creek, and Dry Cottonwood Creek deposits. The main distinctions are the presence of biotite (phlogopite) rims around the French Bar sill sapphires in matrix and the absence of biotite (phlogopite) rims on alluvial Missouri River sapphires. Given that biotite (phlogopite) weathers easily in an alluvial setting, it is possible that any biotite (phlogopite) present was removed during weathering.

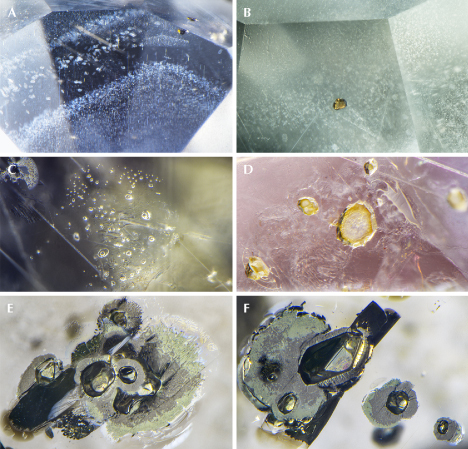

Inclusions/Microscopic Observation. Four of the French Bar sill sapphires were faceted, and five other pieces of rough were polished to add one large flat facet (window), allowing their inclusions to be observed. As with sapphire from many deposits around the world—including Montana’s secondary sapphire deposits—rutile was the most common mineral inclusion in the French Bar sill sapphires. Small flakes and “dust” (minute particles) of exsolved rutile arranged in straight, angular, and hexagonal bands were seen under the microscope as a fiber-optic light tube was moved in various directions around the stationary stone. Occasionally, straight short needles were encountered. These epigenetic exsolutions of fine rutile formations extended in three directions following the three-fold symmetry of corundum, as well as in hexagonal banded patterns following the crystal habit of corundum (figure 12A). In addition, primary protogenetic orange-brown crystals of rutile were identified with micro-Raman spectra (figure 12B).

The second most common inclusion scenes observed in the French Bar sill sapphires were linear tubelike structures oriented in intersecting rhombohedral twin planes (or twin lamellae) following the positive rhombohedral crystal face r (1011) in three directions with angles of 90° (figure 12, C and D). They were often numerous and parallel to one another. These coarse tubelike inclusions are often referred to as “intersection tubules” or more recently “Rose channels” (e.g., Notari et al., 2018), named after Gustav Rose, who first discovered them in calcite in 1868 (Rose, 1868). Rose channels in ruby and sapphire have been referred to in the past as “boehmite needles” and are encountered in corundum from most sources around the world (Hughes et al., 2017). In different stones, whether from French Bar sill or other geographic locations, these coarse needlelike inclusions extended in one, two, or three directions, following the directions of twinning.

Thin film–type inclusions oriented along the basal growth planes were also a very common feature. These were frequently associated with fine, tabular two-phase negative crystals containing a gas phase and amorphous melt (figure 12C). Such silicate melt inclusions were initially trapped as the corundum formed and were later quenched to a glassy state with a contraction bubble during the eruptive event that brought the stones to the surface with subsequent cooling (e.g., Gübelin and Koivula, 1986; Palke et al., 2017).

A 5.81 ct sapphire crystal was removed from a very large piece of French Bar sill basaltic trachyandesite matrix. After grinding and polishing a 14.5 mm long window on this sapphire, more than three dozen angular metallic included crystals with a black appearance were revealed (figure 12, E and F). This specimen was easily moved across a table with a strong 1-inch NdFeB, grade N52 rare earth element magnet. In addition, the characteristic highly metallic luster, hexagonal habit to irregular masses, and black color led GIA’s analytical microscopist, John Koivula, to identify these inclusions as pyrrhotite, an iron sulfide mineral. Confocal micro-Raman spectra also identified pyrrhotite in these inclusions. However, Palke et al. (2023) identified multiple different sulfide minerals in these sulfide inclusions and interpreted them as sulfide melt inclusions rather than single sulfide mineral inclusions. These inclusions in other Montana sapphires, then, are similar to the glassy melt inclusions described above in that some sulfide melt must have been present when the sapphires were growing, which was trapped as a sulfide melt inclusion as the sapphire grew around the melt (also see Palke, 2022).

Other mineral inclusions identified by FTIR consisted of small translucent white to yellow calcite crystals, which were occasionally associated with the thin film–type features (figure 12D). Also frequently encountered were open fissures containing a yellowish epigenetic staining (typically kaolinite), as well as epigenetic mineralizations such as aluminum hydroxide or weathering minerals that filled cracks well after the sapphire crystals formed.

Spectroscopy. Non-polarized UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy on the loose French Bar sill sapphire crystals showed absorption features typical of higher-iron-bearing metamorphic sapphires. These features were consistent with those seen in the secondary Montana sapphires (e.g., Palke et al., 2023). The spectra displayed prominent peaks in the ultraviolet region at 375 and 387 nm, as well as in the visible region with a dominant structure consisting of three bands, with the maxima positioned at approximately 450 nm, accompanied by two side bands at approximately 460 and 470 nm, all of which are related to Fe3+ (figure 13). Additionally, the sapphires in this study exhibiting a subtle blue to green hue also revealed weaker, broader bands related to the Fe2+-Ti4+ intervalence charge transfer. When a polarized spectrum was taken, these broader bands had maxima positioned at approximately 580 nm along the ordinary ray (o-ray) and 700 nm along the extraordinary ray (e-ray), while in non-polarized spectra, these two bands merged to form a larger, broader region of absorption. For those with a pink color component, Cr3+-related bands were revealed consisting of a sharp peak at approximately 694 nm, as well as two broader bands centered at roughly 400 and 560 nm.

FTIR spectra of many of the rough sapphires showed mineral peaks related to calcite, gibbsite, and possibly other unidentified mineral phases, probably due to weathering. These minerals are likely only on the sapphires’ surfaces and not representative of their inclusions. Therefore, the four faceted stones studied here (RK-FBS 030 and RK-FBS 051 through RK-FBS 053) are the most useful for characterizing the FTIR spectra that may be encountered in faceted stones from this locale, where there would be no chance of surface contamination. In these samples, a small, asymmetrical compound band structure was recorded consisting of at least three bands, with the maxima typically positioned at approximately 3220 cm–1. The nature of this band structure is not fully understood; however, it is consistent with sapphires from other Montana sources (e.g., Palke et al., 2023). Inclusions of calcite were also identified with FTIR in one sample (RK-FBS 030), while phyllosilicate minerals such as various micas and clay minerals, including kaolinite, were also recorded in the FTIR spectra of the other three faceted stones.

LA-ICP-MS Trace Element Chemistry. The trace element chemistry of the French Bar sill sapphires is summarized in table 2. Sapphires partially embedded in matrix pieces that measured less than 10 × 10 cm wide and 4 cm thick fit into the sample compartment. LA-ICP-MS trace element chemistry was analyzed on 11 in situ sapphire crystals and on 14 sapphires removed from the French Bar sill basaltic trachyandesite (1 faceted and 13 rough crystals). Their trace element profiles were consistent overall with those reported for secondary Montana sapphires by Palke et al. (2023). This was confirmed by plotting the chemistry of the French Bar sill sapphires, such as the iron versus vanadium and the iron versus chromium plots shown in figure 14 displaying essentially complete overlap with the secondary Montana sapphires. Full results of the French Bar sill sapphire trace element chemistry are provided as supplementary material in table S1.

Photoluminescence Mapping. Photoluminescence maps of Cr3+ in French Bar sill sapphires indicate some samples are zoned in their chromium and likely other trace element concentrations (figure 15, left). The general pattern is similar to that seen in many Missouri River alluvial sapphires with hexagonal growth patterns displayed in the Cr3+ luminescence intensities (figure 15, right).

Oxygen Isotope Analysis. The isotope geochemistry of French Bar sill sapphires (δ18O = 4.0 to 6.7‰, avg. 4.9‰, 7 crystal samples with 14 analyses) overlaps with that of Missouri River sapphires (δ18O = 1.7 to 8.1‰, avg. 5.4‰, 38 samples with 76 analyses), suggesting derivation from similar sources (Turnier et al., 2024). Overlapping trace element chemistry from sapphires at the French Bar sill compared to Missouri River, Rock Creek, and Dry Cottonwood Creek (again, see figure 14) supports the possibility of a shared source but differing magmatic transport rocks.

CRYSTAL MORPHOLOGY: BASIC CRYSTAL SHAPE AND SURFACE FEATURES

The general term secondary deposit is used to include sapphires recovered from colluvial and eluvial deposits both at Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek, as well as the alluvial deposits of the Missouri River. Among the three Montana secondary sapphire deposits, the crystals exhibit some similarities and differences in their morphology, falling into three distinct categories.

Sapphires Retaining the Original Crystal Shape. Some of the secondary sapphires exhibit their original growth features before transporting magma incorporation—this includes hexagonal tablets and partly preserved hexagonal crystals (Berg, 2022). A triangular pattern on the basal plane, which is perpendicular to the c-axis, is rarely encountered in crystals from all three secondary deposits, as well as those from the primary French Bar sill (figure 16).

Sapphires Exhibiting Resorption Surface Features. Features attributed to resorption found in some of these secondary sapphires are based upon two assumptions. First, no further sapphire growth occurred while they were transported by magma. A model presented by Levinson and Cook (1994), which has been universally accepted, relates the formation of gem corundum deposits to subduction zones at depths of about 25–50 km that are later brought to the surface by volcanic magmas. Sapphire (Al2O3) is not in chemical equilibrium with magma of these compositions and would be slowly dissolved. Berg and Landry (2018) and other researchers have reported that the source bedrock for the Missouri River sapphires is unknown, whereas French Bar sill sapphires are found in a basaltic trachyandesite matrix rock. Second, it is assumed that during magmatic transport, resorption occurred, resulting in the features observed on the sapphires. The conditions these sapphires were exposed to during their magmatic transport from the mantle, lithosphere, or lower crust are not well understood. Once these sapphire gems were at the surface, weathering released them from the solidified magma.

Berg (2022) speculated that while the magma was at a higher temperature, coarser etching rapidly formed, followed by a slower creation of smoother etching after the magma cooled and resorption proceeded more slowly.

Sapphires with Features Formed by Weathering and Alluvial Action. Small chips on ridges and projections on secondary sapphires are easily visible with low-to-medium gemological magnification but are perhaps best studied by SEM. Most of these tiny chips likely formed when the sapphire crystals were tumbled in the sediment load of the Missouri River rather than in the washing plant, because the crystals were subjected to fluvial action for exponentially longer than they were in the washing plant and jigs. Smooth rounding of the crystals, seen with the unaided eye, is attributed to abrasion during fluvial transport. Of the three secondary deposits, sapphire crystals from the Missouri River’s various alluvial deposits are the only sapphires to display a smooth rounded appearance. Sapphires from Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek show rounding due to resorption.

COLOR AND MORPHOLOGY OF FRENCH BAR SILL SAPPHIRES

French Bar sill sapphires observed thus far by the authors are typically light to medium tones in hues of green, blue-green, blue, green-blue, pink, yellow, and colorless. Some specimens have displayed a color-change phenomenon, shifting from bluish green to pinkish purple (figure 17), while others have exhibited a strong color change from medium blue to blue-violet.

Because the French Bar sill sapphires are still in the volcanic rock that transported them to the surface, they only exhibit original crystal shape and resorption surface features—not features formed by weathering and fluvial transport.

The general appearance of the in situ sapphires from the French Bar sill matches those found in a small-to-moderate percentage of sapphires in the alluvial deposits in the bars or strath terraces along the banks of the Missouri River, as well as some of the secondary deposits at Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek. Rough French Bar sill sapphires range in shape from flat, tabular hexagonal plates to more equant hexagonal prisms, sometimes apparently modified by rhombohedral faces. The French Bar sill sapphires have prominently rounded crystal edges due to resorption.

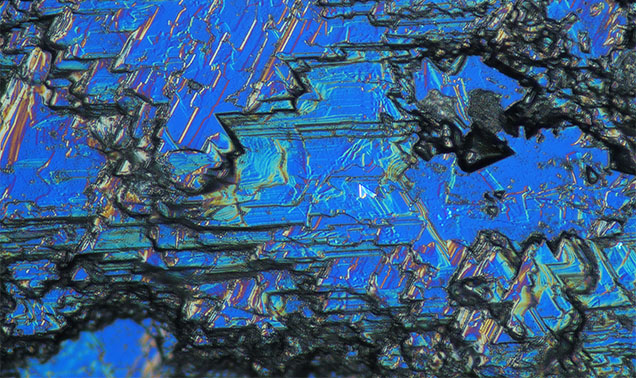

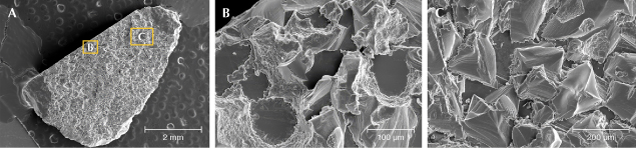

French Bar sill sapphires display a corroded and rounded appearance on all surfaces, which is particularly prominent on the crystal edges, reflecting disequilibrium with the carrier magma during their volcanic transport to the surface. The angular geometric patterns captured in the DIC photomicrograph in figure 18 suggest etching or dissolution of the sapphire in the host carrier magma. SEM images of the surface of a sapphire from the French Bar sill show this intricate and variable resorption (figure 19); the craters are attributed to resorption of the crystal in the magma that cooled from the sill.

COMPARING FRENCH BAR SILL SAPPHIRES TO SAPPHIRES FROM MONTANA’S SECONDARY DEPOSITS

The colors of the French Bar sill sapphires also occur in sapphires at other localities along the banks of the Missouri River, and at the other two Montana secondary deposits (Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek).

The sapphire crystals from Montana’s secondary deposits, as well as from the French Bar sill, are generally tabular or blocky in shape and can also appear somewhat less commonly as hexagonal prisms. The rough stones from Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek, as well as the primary French Bar in situ crystals, often show a rounded appearance, which might cause one to suspect they were subjected to rounding by abrasion from water transport. This is not the case—nearly all the surface features on secondary Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek sapphires, as well as primary French Bar sill sapphires, are entirely from resorption (Berg, 2022). Some Missouri River sapphires have rounding due to alluvial transport, but they also all show resorption features.

In fact, the sapphire morphology from the three deposits generally differs enough to allow identification of the origin of large parcels of rough sapphires from either Rock Creek, Dry Cottonwood Creek, and the Missouri River, even if most of the individual rough stones, or mixed parcels, cannot be traced back to their source (Palke et al., 2023). In most cases, a gemologist using only a microscope will not be able to distinguish between the various secondary faceted Montana sapphires (Kane, 2020), nor can a sophisticated laboratory using advanced gemological testing, including “chemical fingerprinting” with LA-ICP-MS on rough or cut Montana sapphires (Palke et al., 2023). Only sapphires from Yogo Gulch show a distinct difference in inclusion suites and trace element chemistry (Renfro et al., 2018). Because of the extreme differences in price, color, and chemistry, a few of the major independent laboratories following industry nomenclature norms will call all stones from Yogo Gulch “Yogo sapphires” and sapphires from any of the three secondary deposits simply “Montana sapphires.” The inclusions in the French Bar sill sapphires examined thus far—and the trace element chemistry—overlap with those in Montana’s secondary sapphires (Palke et al., 2024).

Spinel Coatings on Alluvial Missouri River Sapphires. Remnants of very dark green (almost black) spinel are preserved in depressions on the surfaces of Missouri River sapphires, where they were protected from abrasion during river transport. Spinel has not been found on the surfaces of sapphires from the other Montana secondary deposits (Berg, 2022). Because spinel has not been identified as a mineral inclusion in these sapphires (Berg and Landry, 2018), it is interpreted to have formed by reaction between the sapphire and iron and magnesium in a mafic magma. Spinel-variety hercynite adheres to some of the sapphires from the Yogo deposits (Clabaugh, 1952), where sapphires are mined from a lamprophyre dike. Also, sapphires from a basalt in the Siebengebirge Volcanic Field in Germany have spinel coronas (Baldwin and Ballhaus, 2018).

Spinel has not been identified on sapphires from the Rock Creek district or from Dry Cottonwood Creek, where the transporting magma was inferred to be of rhyolite or dacite composition (Berg, 2007, 2014). Similarly, spinel was not observed on the surfaces of sapphire xenocrysts in the French Bar sill exposed along Hauser Lake, which is a basaltic trachyandesite. However, spinel on sapphires from the Missouri River deposits suggests that these sapphires may have weathered from a mafic igneous bedrock source that has not been recognized.

Biotite (Phlogopite) Coatings on Primary French Bar Sill Sapphires. All of the in situ French Bar sill sapphires studied by the authors and others have a dark mineral coating composed mostly of biotite (phlogopite) mica (figures 20 and 21). The existence of this coating is different from that of many of the alluvial Missouri River sapphires, for which around 25% of them are characterized by the presence of a dark-colored spinel encrustation (Berg, 2022; Palke et al., 2024). Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of biotite mica in these coatings on the French Bar sill sapphire, and chemical analysis by LA-ICP-MS confirmed them as the magnesium-rich endmember in the biotite group (phlogopite). In the absence of chemical analysis of the mica, previous works described it as biotite. However, biotite is more of a field name for dark mica. When the chemical makeup of dark mica is known, it should be referred to as the dominant mineral species, as the name biotite is not strictly correct. Nonetheless, in recognition of the use of the name biotite in previous works on the French Bar sill, the name has been used here alongside the correct mineral name phlogopite. The sapphire xenocrysts always have a rind of biotite (phlogopite) mica and a thin inner layer of clay (Berg and Dahy, 2002; Berg and Palke, 2016). However, careful SEM imaging and chemical mapping show the presence of a second, very iron-rich layer between the biotite (phlogopite) layer and the sapphire (figure 22). The identity of this inner layer is currently unknown, but future work to identify this phase could help explain the dynamics of magmatic sapphire transportation and how the magmas transporting the French Bar sill and alluvial Missouri River sapphires may (or may not be) related.

As Berg and Palke (2016)—and many researchers over the decades, starting with Kunz in 1893—pointed out, the French Bar sill itself is certainly too small in extent to have supplied all the alluvial sapphires found at the Missouri River. More research will be needed to characterize the mineral coatings of the in situ French Bar sill sapphires in order to understand the dynamics of magmatic transport of those stones compared to other possible magmatic sources of alluvial Missouri River sapphires.

CONCLUSION

Yogo Gulch is the only well-documented primary occurrence of gem-quality sapphire in Montana, although French Bar—the only other in situ deposit of gem-quality sapphire—has been very briefly mentioned in the gemological literature since 1891. Since the initial discovery of sapphires in Montana at Eldorado Bar along the Missouri River in 1865, the geologic source of Montana’s secondary sapphires has remained a mystery.

The French Bar sill primary sapphire deposit is fascinating for the gemologist and mineral collector, as well as scientifically interesting for the geoscientist. This small sill at French Bar contains sparse sapphires and is clearly not the source of most of the sapphires in the deposits along Hauser Lake (frequently referred to as the Missouri River deposits). The French Bar sill sapphires studied here will continue to provide clues about possible bedrock sources for the Missouri River deposit.

Microscopic examination of the sapphires from this unique source, by scanning electron imaging and optical microscopy, shows some rare surface morphologies not seen in other Montana sapphires. However, inclusions and trace element chemistry overlap with Missouri River sapphires, as well as with those from Rock Creek and Dry Cottonwood Creek. The ability to obtain more primary sapphires from the French Bar sill has presented a rare opportunity to investigate this sapphire occurrence in greater detail. French Bar sill sapphires in matrix will continue to be of great interest to the gemologist, collector, and scientist.

.jpg)