Seed Pearls in an Antique Indian-Style Headdress

Identification of seed pearls often poses a challenge to gemologists. Seed pearls are typically smaller than 3 mm and can be of either saltwater or freshwater origin (The Pearl Blue Book, CIBJO, 2022). These tiny pearls have long been used for adornment on clothing, jewelry, and various decorative items.

Recently, GIA’s Mumbai laboratory examined an antique headdress (figure 1) submitted for pearl identification service. The exquisite headdress, which according to the client dates back several decades, featured intricate embroidery on a red velvet base. It incorporated approximately 7,000 light cream and cream-colored pearls, most of which displayed a strong orient. These pearls, ranging from semi-baroque to baroque in shape, were meticulously hand-woven onto the headdress using white silk thread and further secured by a surrounding framework of twisted white metal wire. The headdress itself weighed 240 g, and most of the pearls measured around 2.10 mm, with some larger ones reaching up to 3.40 mm.

Under a 10× loupe, some of the pearls displayed slight wear around the drill hole, while maintaining an overall intact nacre condition with a medium to high surface luster. The pearls embroidered on top of the headdress displayed nacreous overlapping aragonite platelets (platy structure) patterns, which are typically observed in pearls from a saltwater environment. Those on the side portion exhibited slightly broader platy patterns, which are common in freshwater pearls. Under long-wave ultraviolet radiation (figure 2, left), most of the pearl samples showed weak greenish yellow fluorescence, with a small percentage showing yellowish brown. A similar weaker reaction was observed under short-wave ultraviolet radiation (not shown).

When exposed to X-ray fluorescence, the pearls on top of the headdress were inert, indicating their saltwater origin. In contrast, the pearls on the side portion showed a strong yellowish green fluorescence due to high manganese contents, indicating a freshwater origin (figure 2, right). Interestingly, some freshwater pearls also displayed an orangy red fluorescence, suggesting the presence of vaterite, a less commonly observed form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) compared to aragonite or calcite (Winter 2021 Lab Notes, pp. 377–378). Due to the size and delicate nature of the headdress, further analysis of chemical composition using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry was not feasible.

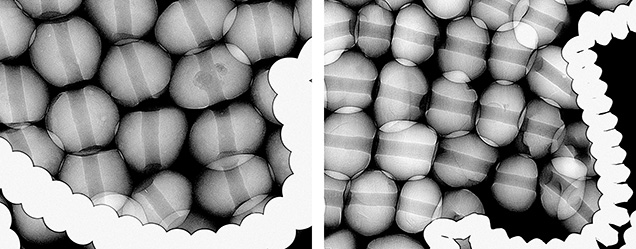

To study the internal structures, the authors performed random sampling using real-time microradiography (RTX) imaging (figure 3). Internally, most of the saltwater pearls exhibited small organic-rich cores with fine growth arcs, while other samples displayed tight to minimal structures with a few fine growth arcs toward the outer nacre. These internal structures were similar to those observed in natural pearls from the Pinctada species. Similarly, the freshwater pearls displayed natural structures with growth arcs throughout the pearl, consistent with natural freshwater pearls from GIA’s research database (Summer 2021 Gem News International, pp. 167–171). Twisted linear structures or voids, which are commonly found in non-bead cultured Chinese freshwater pearls, were also observed in a minority of the tested samples (K. Scarratt et al., “Characteristics of nuclei in Chinese freshwater cultured pearls,” Spring 2000 G&G, pp. 98–109).

Although the identification of seed pearls has always presented challenges and limitations, advancements in equipment and instrumentation available at GIA laboratories enable the detailed analysis of even the most minute structures and features in pearls, whether natural or cultured.

.jpg)