History of the Chivor Emerald Mine, Part II (1924–1970): Between Insolvency and Viability

ABSTRACT

The history of the Chivor emerald mine in Colombia is a saga with countless twists and turns, involving parties from across the globe. Indigenous people initially exploited the property, followed by the Spanish in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before abandonment set in for 200 years. The mine was rediscovered by Francisco Restrepo in the 1880s, and ownership over the ensuing decades passed through several Colombian owners and eventually to an American company, the Colombian Emerald Syndicate, Ltd., with an intervening but unsuccessful attempt by a German group organized by Fritz Klein to take control. With the Colombian Emerald Syndicate succumbing to bankruptcy in 1923, the property was sold and then transferred in 1924 to another American firm, the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation. Under the new ownership, stock market speculation played a far more prominent role in the story than actual mining. Nonetheless, periods of more productive mining operations did take place under managers Peter W. Rainier and Russell W. Anderton. Yet these were not enough to prevent the company, renamed Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc. in 1933, from entering insolvency in 1952 and being placed into receivership. Leadership by Willis Frederick Bronkie enabled the firm to regain independence in 1970 and shortly thereafter to be sold in a series of transactions, with Chivor gradually being returned to Colombian interests.

INTRODUCTION

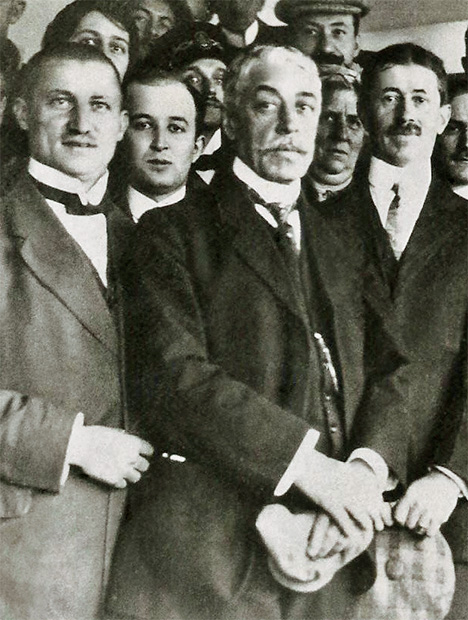

Many legends are told about the history of the Chivor emerald mine.1 The story begins with the sporadic working of the Colombian mine by indigenous people before being sought out by Spanish conquistadores in the first half of the sixteenth century. The property was exploited by the Spanish in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and then forgotten in the jungle for a period of more than two centuries after 1672. Schmetzer et al. (2020) chronicled the first part of the modern era commencing after the 200-year break, covering from 1880 to 1925. During that interval, Colombian miner Francisco Restrepo searched for and rediscovered the mine, and mining titles were granted to him and his associates in 1889. Through a series of transactions, the mining titles and land in the area came under the ownership of the Compañía de las Minas de Esmeraldas de Chivor, a Colombian entity in which Restrepo was involved. Only intermittent operational activities took place until 1912, when the German gem cutter and merchant Fritz Klein joined Restrepo with an increased focus on the operational side. Early mining by Restrepo and Klein yielded several finds promising enough for them to travel to Germany together in 1913 to seek investors (figure 1). Further work was curtailed one year later, however, when Restrepo died in 1914 and Klein, who had hoped to purchase the mine with German funding, was thwarted by the outbreak of World War I.

When hostilities ended, Klein sought to recommence his efforts to buy the mine in 1919, but an American corporation, the Colombian Emerald Syndicate, Ltd., had in the interim obtained an option to purchase the mine. That option was exercised, and the mine was sold in December 1919 to two key representatives of the American group, Wilson E. Griffiths and Carl K. MacFadden. On behalf of the Colombian Emerald Syndicate, mining operations were conducted from 1919 to 1924 under the alternating leadership of the English miner and entrepreneur Christopher Ernest Dixon, who had lived in Colombia since the late 1880s, and Klein (figure 2), who served two terms of several months each under contracts with the new owners. Although both Dixon and Klein reported good production, the financial situation of the company nonetheless deteriorated, and an involuntary bankruptcy petition was filed against the Colombian Emerald Syndicate in 1923. The Chivor mine was sold in 1924, and it is here that the present paper, Part II, picks up the tale.

The following decades of Chivor’s operational history were dominated by three key mine managers or administrators, Peter W. Rainier (1890–1945), Russel W. Anderton (1909–1982), and Willis Frederick Bronkie (1912–1979).2 Both Rainier (Green Fire, 1942) and Anderton (Tic-Polonga, 1953, 1954)3 published books recounting their adventures, and Bronkie’s successful management was the subject of several reports, including those by Johnson (1959, 1961). These publications, however, fall short of fully elucidating the mine’s modern development, and the shortcomings are analogous to those faced in Part I with Klein’s work (1941, 1951). For example, Rainier’s account provided few actual dates, and Anderton likewise offered little to contextualize the timeline. Consequently, the present authors sought to fill existing gaps and present a comprehensive survey through reliance on contemporaneous primary documents and references. This second installment focuses on an overview of the half-century after the bankruptcy of the Colombian Emerald Syndicate, from 1924 to 1970. Following brief interim transactions in 1924, Chivor was owned throughout this period by a single American entity, operating first under the name Colombia Emerald Development Corporation and from 1933 as Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc. A summary of the main events is given in table 1.

1See, e.g., Peretti and Falise, 2018.

2See, e.g., Weldon et al., 2016.

3Tic-Polonga was published in the United States in 1953 and in the United Kingdom in 1954. The 1954 edition was consulted for purposes of this study, and references henceforth will be to that publication.

SOURCES

The search for contemporaneous materials spanned South America, North America, and Europe (i.e., Colombia, the United States, and the United Kingdom). The primary documents found were compared with the known literature on the topic. Full citations for the principal existing publications consulted are summarized in the reference list. Other primary documents, such as governmental and judicial reports and decrees that may appear in broader compendiums, certain trade periodicals, archived contracts, business records, newspaper articles, personal correspondence, etc., are identified to the extent feasible in the footnotes, along with brief citations to publications included in the reference list.

Colombian materials were found in the form of government publications printed, typically anonymously, in the “Diario Oficial (Colombia),” in the “Gaceta Judicial (Colombia)” of the Corte Suprema de Justicia (Supreme Court), and in the reports of ministries or other government offices, especially in the series “Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso.” These included legislative texts, decrees, governmental or judicial pronouncements, and statements on petitions and complaints. The Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia) in Bogotá further proved to be a repository of files collecting correspondence, notarial acts (escrituras), and attachments reflecting mine title transfers, sales of shares between various shareholders, and agreements shedding light on the ongoing fluctuations in Chivor ownership and related events.4

4Most germane at the Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia) in Bogotá, were several notarial acts (escrituras) designated herein by escritura number and date. Likewise instructive was the file “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, which contained documents covering 1929 to 1954 and detailing mine boundaries and history.

Governmental collections of a similarly useful nature were found in the United Kingdom. Particularly apposite was correspondence and associated materials archived at the Royal Academy of Music, London, where the legacy of Peter Rainier’s sister Priaulx is preserved.

Relevant information was also found in periodicals, largely from American publishers, concerning mining and the mining industry, such as the Engineering and Mining Journal, Minerals Yearbook, or Mineral Trade Notes. Financial sector periodicals were equally pertinent, and publications of U.S. universities yielded material on alumni who went on to work as mining engineers or geologists at Chivor.

Even online resources added to the available contemporaneous data. Noteworthy in this regard were digitized compilations of records detailing transit of persons, such as passenger lists maintained by the United States Immigration Office in New York. Those records detailed information that could incorporate departures and arrivals through national borders, starting points, destinations, and, most importantly, specific dates to help establish or corroborate event time frames. Similarly insightful were digital archives of newspapers across the United States, which enabled a view of events as presented to the public.

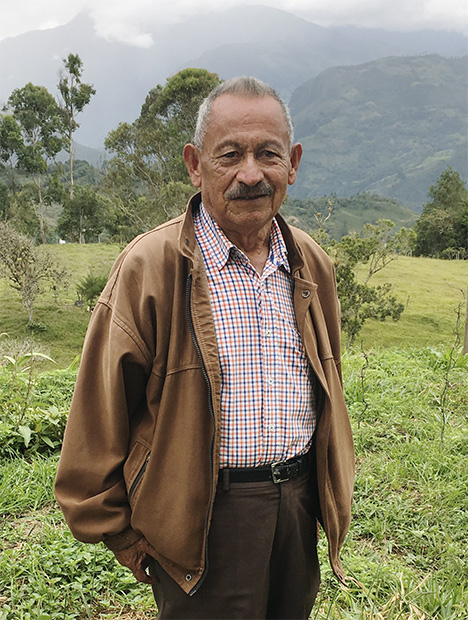

Finally, personal information obtained from eyewitnesses such as Peter Rainier, Jr., Manuel J. Marcial, don Alfonso Montenegro (figure 3), Renata de Jara, Gonzalo Jara, and Robert E. Friedmann, was invaluable in achieving the aims of this study.

CHIVOR AS A SUBJECT OF STOCK MARKET SPECULATION (1924–1927)

To recap the period from 1924 to 1925 bridging Parts I and II of this study, the mining titles for Chivor 1 and 2 and the related land ownership were sold in a bankruptcy sale on or about August 23, 1924, to the recently formed Chivor Emerald Corporation.5 The price paid was only US$7,800 to $8,000, depending on the report consulted,6 which did not even cover liabilities in the range of $45,000 of the former owner, the Colombian Emerald Syndicate (see part one of this article).7 The Chivor Emerald Corporation had been incorporated on March 6, 1924, under the laws of the State of Delaware, by Samuel C. Wood, Harry C. Hand, and Raymond J. Gorman.8 The stated corporate purpose was to “mine and prepare for market emeralds, diamonds.”9 The three named individuals served as registrants of numerous corporations across a spectrum of industries in the 1920s (e.g., motion pictures, radio accessories, petroleum, and rubber), operating via a business model that acquired bankrupt or troubled companies (or their assets) and resold them after improvement in the price.10

Another new entity, the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, was then incorporated on November 7, 1924, likewise in the state of Delaware, by Edmund J. MacNamara (1874–?), Ernest W. Brown, and William B. Anderson.11 The intended business was “to mine, manufacture and deal in precious stones, emeralds, rubies, diamonds, jades and garnets.”12 The Chivor claims and land were transferred to that company in late 1924 in exchange for stock.13 The Chivor Emerald Corporation thereafter served merely as a holding company, owning approximately 40 percent of the capital stock in the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation but no other assets.14 Per available evidence, the two firms were headquartered together in New York City and generally controlled by a common group of individuals,15 with the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation apparently established to take over and carry on the emerald business as the operating enterprise. Registration of the two companies in Colombia took place in February 1925 for the Chivor Emerald Corporation16 and in July 1925 for the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation.17 The governor of Delaware subsequently repealed the charter of the Chivor Emerald Corporation in 1961 for failure to pay taxes.18

A number of the principal figures involved in leadership of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation were associated with the Lewisohn group of companies, an American offshoot of the Lewisohn family mercantile business based originally in Hamburg, Germany.19 The brothers Leonard (1847–1902) and Adolph (1849–1938) Lewisohn had followed their older brother Julius in the second half of the 1860s from Hamburg to New York to assist with the American branch. Julius returned to Hamburg in 1872, and Leonard and Adolph went on to create one of the larger copper mining and processing empires in the United States between 1880 and 1900, operating as Lewisohn Brothers.20 The German and American branches of the business formally separated in 1887.

5The Cumulative Daily Digest of Corporation News, No. 3 (1924), pp. 150, 161. This entity should not be conflated with an unrelated Canadian company of the same name that was active at Chivor decades later in the 1990s.

6The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 9, 1927, p. 22; The New York Times, January 9, 1927; The Bridgeport Telegram, January 10, 1927, p. 5; The Tribune (Coshocton, Ohio), January 10, 1927, p. 4; The New York Times, January 28, 1927; The New York Times, February 20, 1927; Jewelers’ Circular, 94, No. 4 (1927), p. 61; Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927, p. 40.

7Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities, 6 (1938), p. 227.

8State of Delaware, Department of State, Division of Corporations, Entity Details; The Morning News, March 7, 1924, p. 11.

9The Morning News, March 7, 1924, p. 11.

10The Morning News, November 15, 1923, p. 9; The Morning News, April 14, 1925, p. 11; The Morning News, July 1, 1925, p. 9; Arizona Republic, March 13, 1929, p. 4.

11State of Delaware, Department of State, Division of Corporations, Entity Details; The Morning News, November 8, 1924, p. 13; The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1924, p. 33; The Cumulative Daily Digest of Corporation News, No. 4 (1924), p. 222; Winkler, 1928.

12The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1924, p. 33.

13The Cumulative Daily Digest of Corporation News, No. 4 (1924), pp. 209, 222; Winkler, 1928; Rainier, 1929, 1931.

14Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities, 11 (1946), p. 149.

15For example, the reported addresses for the two companies during the late 1930s and early 1940s were identical, given as 32 Broadway, New York City. Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities, 6 (1938), p. 205; Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities (1944), p. 147.

16Escritura 344, February 16, 1925, Notaria 1, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

17Escritura 1607, July 11, 1925, Notaria 1, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

18State of Delaware, Executive Department, Chapter 465 Proclamation, January 16, 1961.

19Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities, 6 (1938), p. 227.

20Engineering and Mining Journal, 110, No. 15 (1920), p. 722; Albrecht, 2013.

By the time of the 1924 Chivor transaction, the Lewisohn group of companies had already been involved in mining activities in Colombia for several years. In 1916, the Lewisohn Brothers and Adolph Lewisohn & Sons formed the South American Gold and Platinum Company. After buying multiple mines in Colombia and merging with various other entities, this corporation had become the largest producer of noble metals (gold and platinum) in that country. Frederick Lewisohn (1881–1959), one of Leonard Lewisohn’s sons, served as a vice president of the company.21 The Lewisohn group likely opted to take advantage of the low price at which the assets of the bankrupt Colombian Emerald Syndicate could be acquired (as compared to the £46,000, equivalent to US$230,000, previously paid for the Chivor mines in 1919),22 to establish a new line of business in emerald mining.

The three listed incorporators of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation all held roles (e.g., president, secretary, or director) in different mining companies associated with the Lewisohn group, especially the Seneca Copper Corporation and the Santa Fe Gold & Copper Mining Company.23 MacNamara, a mining engineer and entrepreneur having wide-ranging participation with Lewisohn Brothers entities, stepped in as president of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, a position that he would continue to fill in the years ahead.24 After the transfer of assets of the Chivor Emerald Corporation to the new company, Frederick Lewisohn acquired between 40 and 50 percent of the authorized capital stock of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation for a price in the range of 10 cents per share, or approximately $50,000.25 Shares were also being advertised to the American public by March 25, 1925, for a subscription price of $2 per share.26 As of May 19, 1926, the company was listed on the Boston Curb Exchange at $1⅞ per share.27

In the next stage of Chivor’s history, the owning entity became entangled in a stock market scandal while operational activity was minimal. As to the latter, the first mining engineer sent to Chivor by the new mine owners was William Burns (1885–1962), who had already been working for the Lewisohn group in various functions (e.g., as manager of the Santa Fe Gold & Copper Mining Company or as secretary of the Rosemont Copper Company).28 Burns reportedly had also performed development work in the 1920s at Chivor for the former owner, the Colombian Emerald Syndicate.29 During his tenure, Burns expended over $40,000 on the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation’s behalf on the property, but the resultant emeralds produced were not worth over $4,000.30 Burns later resigned, and he was succeeded by mining engineer Charles Mentzel (1881–1949), likewise previously associated with the Lewisohn-owned Santa Fe Gold & Copper Mining Company and having gained experience in Colombia in 1916 and 1917.31 Mentzel arrived at Chivor in late May 1926, and Burns returned to New York on June 13, 1926.32

21The New York Times, June 13, 1919; The Economist, 89 (1919), p. 39; The Magazine of Wall Street, 25 (1919), p. 57; The New York Times, July 5, 1959, p. 56.

22Escritura 3084, December 27, 1919, Notaria 1, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

23The Copper Handbook, 10 (1911), pp. 1528–1529; Trow’s New York Copartnership and Corporation Directory, 63 (1915), p. 912; Trow’s New York Copartnership and Corporation Directory, 66 (1919), p. 1019; The Copper Handbook, 14 (1920), pp. 1256–1257; Moody’s Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities, 2, Part 1, Industrial Section (1921), pp. 1369–1370; Engineering and Mining Journal, 113, No. 9 (1922), p. 376.

24The Mines Handbook, 12 (1916), p. 1005; Mineral Resources of Michigan (1917), p. 53; Engineering and Mining Journal, 122, No. 16 (1926), p. 602; The New York Times, August 7, 1926; The New York Times, August 10, 1926; In re Idaho Copper Corporation, Deposition of Keyes Winter, Deputy Attorney General, State of New York, Supreme Court of New York (Sept. 8, 1926); The New York Times, October 12, 1926; Engineering and Mining Journal, 123 (1927), p. 106; Poor’s Register of Directors of the United States (1928), p. 918; Poor’s Register of Directors of the United States and Canada (1932), p. 1291.

25The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 6, 1927, p. 2; Salt Lake Telegram, January 13, 1927, p. 5; The New York Times, January 28, 1927.

26The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), March 28, 1925, p. 17.

27The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), May 19, 1926, p. 12.

28Harvard Alumni Bulletin 20 (1917), p. 440; American Mining & Metallurgical Manual (1920), p. 89.

29Brock, 1929.

30Ibid.

31Engineering and Mining Journal, 101, No. 15 (1916), p. 663; Engineering and Mining Journal, 103, No. 11 (1917), p. 476; Brock, 1929.

32File William Burns, List of United States Citizens Arriving at Port of New York, June 1926, Ancestry.com.

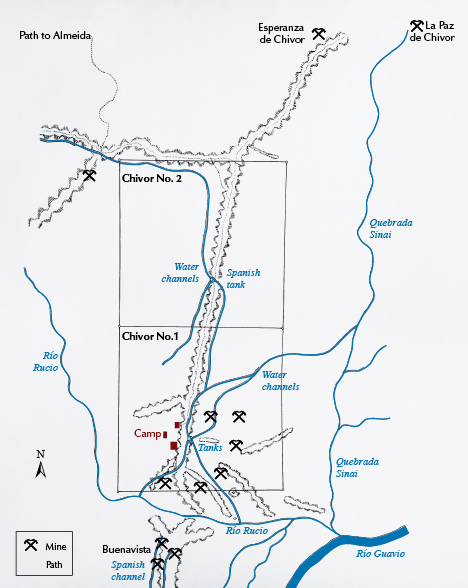

For operational purposes, materials published by the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation suggest that the company was only focusing on and/or asserting claims over the Chivor 1 and 2 mines, excluding the other three mines of the Chivor group.33

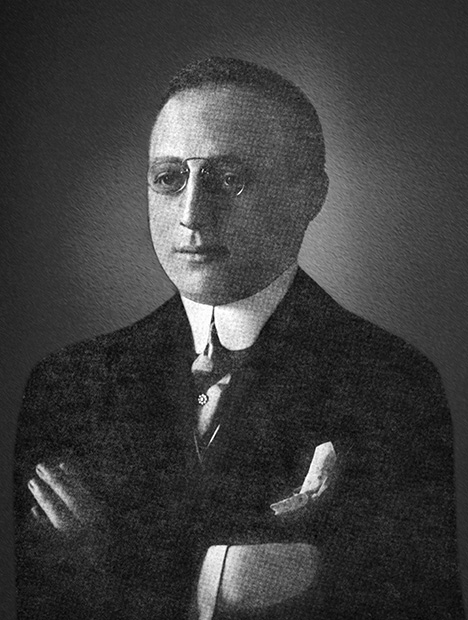

Meanwhile, as to the stock market machinations, Frederick Lewisohn had transferred his package of shares to George Graham Rice (1870–1943, figure 4), either directly or through Rice’s brother-in-law Frank J. Silva as a conduit, for a price of 75 cents per share.34 Rice then began to market the shares via his weekly promotional circular the Wall Street Iconoclast,35 which was sent to a mailing list of 600,000 recipients.36 Rice was one of the most infamous financial manipulators of the era, having already spent time in prison on multiple occasions for various crimes of fraud and theft.37

Rice’s tactics are exemplified by two issues of the Wall Street Iconoclast we were able to locate from July and August 1926.38 In those issues, Rice promoted the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, as well as another Lewisohn entity sold on the Boston Curb Exchange, the Idaho Copper Company.39 Rice aggressively recommended buying shares of the Lewisohn-controlled Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, reporting that the Lewisohn family had acquired the mines in the winter of 1924/1925. He also identified MacNamara as president of the company, emphasizing MacNamara’s dual role as vice president of the Lewisohn Exploration & Development Corporation.40 Rice likewise played upon the expertise of mining engineers Burns and Mentzel. Notably, it has been reported that Burns’s resignation was prompted when he “learned that Rice was selling the stock and using his name as bait.” Mentzel, prior to his departure for Colombia and without having seen the mine, had already written a report in the Wall Street Iconoclast that valued the property at $5,000,000.41 One of Rice’s strategies was thus to use the reputation of an industrial family well known in the mining business—Lewisohn—to incentivize investment.42

An additional strategy was found in Rice’s glowing portrayal of emerald production and valuation. The Wall Street Iconoclast reported extraordinarily rich finds such as 23,500 carats in June 192643 and calculated sensationally high values for the mining property and stock, claiming that a share “had a real value of between $50 and $75” and that the mines owned by the company “were valued at $100,000,000 and were capable of producing an annual income for investors of between $2,000,000 and $5,000,000.”44 The stock of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation rose over a period of 14 weeks from $1 to $175⁄8.45 In reality, however, half of the 23,500 carats highlighted by Rice were worthless stones, and the remainder had an estimated value of 50 cents per carat.46 The company reported a loss of $57,000 for 1926.47 As one mining engineer who worked under the Lewisohns at Chivor would later summarize: “I guess they [the Lewisohns] made more money on the stock market than mining.”48

33Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, The Story of Emeralds (Undated), 10 pp. The map included appears to be prepared after Canova (1921) but eliminates the other three mines shown on the original version.

34The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 6, 1927, p. 2; The New York Times, January 6, 1927; The New York Times, January 28, 1927; Engineering and Mining Journal, 123 (1927), p. 635.

35For example, The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 102, July 15, 1926; The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 105, August 5, 1926.

36The Pittsburgh Press, February 28, 1928, p. 33.

37Rice, 1913; The Scranton Republican, August 28, 1926, p. 15; Plazak, 2006; Thornton, 2015.

38The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 102, July 15, 1926; The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 105, August 5, 1926.

39The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 102, July 15, 1926; The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 105, August 5, 1926. The Idaho Copper Company was also known as the Idaho Copper Corporation. Thornton, 2015.

40Most likely a reference to the Lewisohn Exploration & Mining Co. or to the General Development Co.

41Brock, 1929.

42Engineering and Mining Journal, 122, No. 16 (1926), p. 602.

43The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 102, July 15, 1926; The Wall Street Iconoclast, 5, No. 105, August 5, 1926.

44The New York Times, February 20, 1927; Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927, p. 40.

45St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 6, 1927; The Pittsburgh Press, February 28, 1928.

46Brock, 1929.

47The Cumulative Daily Digest of Corporation News, No. 2 (1927), p. 165.

48The Billings Gazette, May 16, 1954, p. 6.

Such discrepancies began to come to light as a result of actions beginning in 1926 by New York State Attorney General Albert Ottinger. Under the Martin Act (New York General Business Law, Article 23-A, Sections 352–353), he targeted the Wall Street Iconoclast, Rice, Silva, the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, MacNamara, and Frederick Lewisohn.49 In injunction proceedings, Ottinger claimed that “not over a spoonful of stones and only two of those salable, have ever been taken from the mines.”50 A related investigation by Deputy Attorney General Keyes Winter led him to conclude “that the total value of the output of the mines for two years did not exceed $13,000, and that many of the emeralds obtained were in an uncrystallized state and could not be marketed.”51 Such numbers contrasted blatantly with claims proffered to promote sale of the stock, which indicated that emeralds of fabulous quality weighing between 28 and 80 carats, with a value between $100 and $500 per carat, had been found at Chivor.52

A preliminary injunction restraining promotion, advertising, and sale of Colombia Emerald Development Corporation stock had been issued by early January 1927. It was then made permanent in a ruling handed down on or before February 19, 1927, in the New York Supreme Court (i.e., the trial-level state court).53 Rice and associates were thereby restrained “from the sale of the stock of the emerald corporation unless complete information about the concern is furnished,”54 and not a single share of the stock could be sold without giving a detailed explanation of the actual profit and losses from mining operations.55 Although the injunction was later vacated in part to the extent that it applied to the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, Frederick Lewisohn, and MacNamara, on account of insufficient evidence to establish the actual personal participation of Lewisohn and MacNamara in fraudulent practices, the restraint against the Wall Street Iconoclast, Rice, and Silva remained in force.56

Rice ultimately avoided serious prosecution in connection with his dealings related to the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation. Still, matters pertaining to the Idaho Copper Company proceeded to trial and led to him being found guilty in 1928 and sentenced to four years in prison.57 As an anecdotal footnote, while incarcerated at the federal penitentiary in Atlanta on those charges, Rice became a friend of another prominent inmate, Al Capone.58

By the end of 1928, both the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation and the Idaho Copper Company had been delisted from the Boston Curb Exchange.59

49The New York Times, August 7, 1926; The New York Times, October 12, 1926.

50The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 6, 1927, p. 2.

51The New York Times, February 20, 1927; Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927.

52The New York Times, February 20, 1927; Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927.

53The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 6, 1927, p. 2; The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 9, 1927, p. 22; The New York Times, January 9, 1927; The Bridgeport Telegram, January 10, 1927, p. 5; The Tribune (Coshocton, Ohio), January 10, 1927, p. 4; The New York Times, January 28, 1927; The New York Times, February 20, 1927; Jewelers’ Circular, 94, No. 4 (1927), p. 61; Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927, p. 40.

54Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1927.

55The New York Times, February 20, 1927.

56The New York Times, May 7, 1927.

57Plazak, 2006.

58Ibid.

59Star Tribune (Minneapolis), December 18, 1928.

CHIVOR UNDER PETER W. RAINIER (1927–1931)

During late 1926 or early 1927, the president and directors of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation decided to hire a new mining engineer to oversee on-site operations at the Chivor mine in Colombia, replacing Mentzel. The mine had been unprofitable for the preceding two years, but the ongoing legal proceedings in New York involving MacNamara and Frederick Lewisohn likely rendered the alternative course of simply closing the mine inadvisable. The engineer selected as Mentzel’s successor, apparently under an initial contract of six months,60 was Rainier (figure 5). Born in Transvaal, South Africa, Rainier had obtained mining experience in countries such as Nigeria, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and South West Africa (Namibia).61 At the time of his engagement, Rainier was living in the United States with his family. Mentzel did not, however, immediately leave Colombia and remained active in the country during 1928 and 1929, presumably still with the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation in some capacity.62

Rainier began his work in Colombia in 1927, leaving his family behind in the United States when his son Peter W. Rainier, Jr. (born August 1926), was only a few months old.63 His wife and children would later join him at Chivor in 1928. Efforts at the mine started with repairing the infrastructure, after which Rainier was able to improve the yield of operations and the quantity of facet-grade gem material. At that time, the traditional open-cast step-cutting technique (figures 6 and 7) continued to be employed. Small terraces or steps were cut in the extremely steep mountain surface, and the loose debris was washed away by a flood of previously collected water. Crystals were carefully removed by hand from the emerald-bearing veins or cavities within the host rock.

In 1929, Rainier published a study describing his mining operations at Chivor, and he traveled to New York to present the paper at a conference of the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers in February 1930.64 It is also logical to surmise that the trip to New York would have provided an opportunity to meet with his employer concerning the mining activities.

After Rainier returned to Colombia, he was joined at Chivor by geologist Verner A. Gilles (1886–1954) from April to August 1930 for geological mapping and evaluation of the mine.65 Like many others sent to Chivor, Gilles had experience working for companies owned by the Lewisohn family.66 His evaluation resulted in a report, dated September 20, 1930, that provided insight into the production and cost of mining.67 In the period from 1925 to 1929, the mine yielded 137,000 carats in total, beginning from a low of 4,000 carats in 1925, the first year of mining operations under the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation, followed by a large quantity of low-grade stones in 1926. The costs of mining operations from 1926 to 1929 aggregated $278,000, and it was noted that a maximum of 250 workers were on the payroll of the mine (figure 8). The total selling value of the emeralds produced from 1925 to 1929 was calculated at $274,000, indicating that the average price received per carat was approximately $2. Such figures evidenced that the mine was not generally profitable, with mining costs versus emerald sales value roughly equal at best. The numbers also offered a counterpoint to the more optimistic estimation apparently held by Rainier, who would later opine that he handled “emeralds worth more than one million dollars” during his years of responsibility over the mine.68

Gilles’s report further addressed geological aspects pertaining to the reserve of emerald-bearing rock at Chivor, concluding:69

It is almost impossible to give an estimate of the value of this enormous deposit of emerald bearing rock. To sample the deposit is out of the question. Even drilling would not give an adequate idea of its value, due to the fact that the ratio between gangue rock and valuable mineral contents is so great. There is but one way to tell what the deposit is worth, and that is to work it out. Here is where the great hazard of emerald mining must be considered. Working out the emerald bearing formation now in reserve may mean a handsome profit and on the other hand it may mean a great loss. After all is said and done the question of profit in this case of mining is largely a matter of luck.

As previously noted, Gilles departed from Colombia in late August 1930, approximately concomitant with the arrival of American mining engineer Robert Elmer Sylvester (1904–1988, figure 9) to assist Rainier.70 Sylvester’s contract had come through the Lewisohn group of companies,71 and a two-year stay in Colombia was planned.72 His tenure would actually end, however, by October 1931 when he returned to New York.73

60Rainier, 1942.

61Weldon et al., 2016. Insofar as Weldon et al. (2016) chronicled Peter W. Rainier’s account as presented in Green Fire (1942), the following discussion will focus more broadly on the chronology as it relates to independent documentation.

62File Charles Mentzel, List or Manifest of United States Citizens Arriving at Port of New York, February 1928 and February 1929, Ancestry.com.

63Rainier, 1942; Peter W. Rainier, Jr., pers. comm. 2017.

64Rainier, 1929, 1931. The study was initially published in 1929 and was then reprinted in expanded form in 1931, incorporating comments generated during the discussion that followed oral presentation of the paper before the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers in February 1930 in New York. A Spanish translation was published in 1934. Rainier, 1934. See also The Wilkes-Barre Record, March 21, 1930, p. 2.

65Verner A. Gilles left Colombia on August 31 and returned to New York on September 10, 1930. File Verner Gilles, List of United States Citizens Arriving at Port of New York, September 1930, Ancestry.com.

66The Billings Gazette, May 16, 1954, p. 6.

67Gilles, 1930.

68Gilles, 1930.

69Rainier, 1942.

70Robert Elmer Sylvester received his degree from the School of Mines and Metallurgy, Institute of Technology, University of Minnesota, in 1927. He married in July 1930 and arrived at Chivor with his wife Josephine at the end of August 1930. Alumni Blue Book, School of Mines and Metallurgy, Institute of Technology, University of Minnesota (1950), 13, p. 135; Rebecca Toov, University of Minnesota Archives, pers. comm. 2018.

71The Bismarck Tribune, September 9, 1930, p. 3.

72The Billings Gazette, July 20, 1930, p. 13; Minnesota Chats, January 2, 1931, p. 3.

73File Robert Sylvester, List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigration Officer at the Port of Arrival, New York, October 1931, MyHeritage.com.

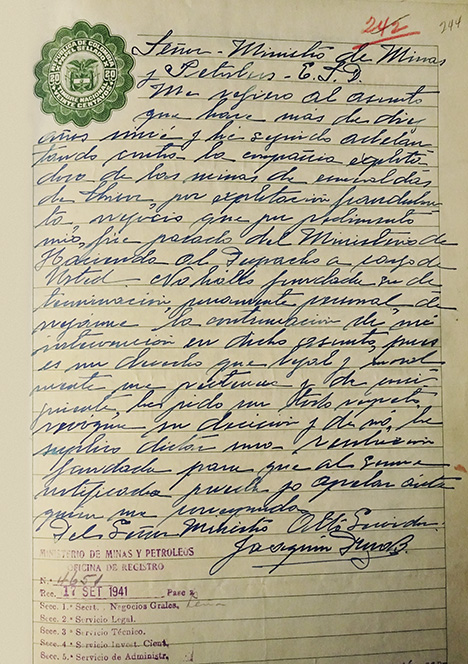

As these operational activities were taking place, in the background ownership and control of the Chivor mines had become the subject of a legal dispute, referred to as the Joaquín Daza case. Joaquín Daza B. submitted a petition dated December 27, 1929, to the Colombian government, claiming that the Chivor mine partly overlapped with his property and that mining operations were being conducted on his land.74 He proposed that he be awarded financial compensation for the infringement. According to Green Fire, Rainier rejected such a proposal after Daza personally visited the mine with his demands.75

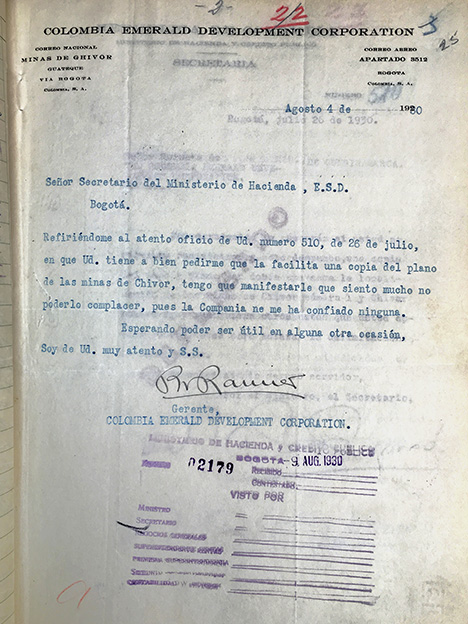

In the more formal proceeding and at the request of the government, Rainier responded to Daza’s claims via a letter dated August 4, 1930.76 Therein, Rainier explained that he had no exact map of the mine boundaries, as no such document had been provided by his employer (figure 10). In connection with the case, the mine was inspected during the period from late January to early February 1931 by two government officials, i.e., the lawyer Alfonso Torres Barreto and the engineer Miguel Alvarez Uribe, together with Daza, Rainier, and Sylvester, and a report was issued on February 7, 1931. Yet no final resolution was reached, and ongoing consideration by the government was reflected in documents dated in 1934, 1935, and 1939.77

The consideration apparently intensified in January 1941, when the mine was examined once again by Colombian officials. A report by engineer Nicolas Rosso, dated January 29, 1941,78 incorporated a map showing currently mined sites, estimated mine boundaries, and relevant infrastructure (figure 11). Discussions between Rosso and Daza in Guateque had preceded the inspection, and Daza then reiterated his claims in letters submitted to the government dated from August to October 1941, wherein he also augmented his petition to request consideration of titles to the adjacent mines of Buenavista and Mundo Nuevo (figure 12; see also figure 25). Even well into the 1950s, government documentation showed that the matter remained open, with the last recorded activity in the case dated to October 1958 and with no known definitive solution or final result.79 Such a scenario contrasted markedly with Rainier’s recollection in Green Fire, where he represented that shortly after the 1931 examination of the mine’s boundaries, he received a telegram from the company’s agent in Bogotá declaring: “Government decided Joaquín’s claim groundless.”80

74File “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

75Rainier, 1942.

76File “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

77Ibid.

78Ibid.

79Diario Oficial (Colombia), 96, No. 30056 (1959), p. 597.

80Rainier, 1942

Meanwhile, during the 1930 to 1931 period, both personal circumstances involving Rainier and hostilities at the mine property likely impacted operations, leading to possibly multiple temporary reductions or stoppages of work on behalf of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation. From a personal standpoint, Rainier and his wife Margaret acquired a hacienda known as “Las Cascadas” south of Río Rucio in the Departamento de Cundinamarca. The family moved there from Chivor in 1930 or 1931, when his son Peter W. Rainier, Jr., was four.81 Rainier was also involved, at least initially, in establishing operations at the hacienda. Nonetheless, he remained active as mine manager over Chivor, assisted by Sylvester, during the January and February 1931 developments in the Joaquín Daza case.82

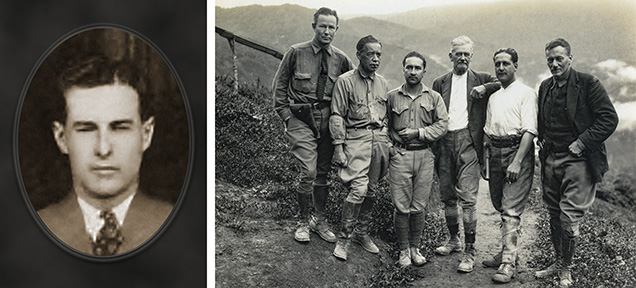

Regarding hostile conditions at the mine, security concerns would appear to have arisen at some point after the February 1931 inspection in the Joaquín Daza case, when the property became the target of repeated attacks from bandits. Peter W. Rainier, Jr., remembered: “After he [Peter W. Rainier, Sr.] got Las Cascadas in operation then he went back to Chivor and recaptured Chivor [from bandits] with his friends Chris Dixon and his sons and a couple of other guys and operated the mine for a while.”83 Similarly, a photograph from that era showed Rainier, Christopher Ernest Dixon (figure 13), Dixon’s sons, and Sylvester (figure 14)84 and included a handwritten notation on the back (presumably by Rainier) that read: “Our gang at Chivor during the bandit fighting days.” That photo must have been taken before the close of October 1931, as that was when Sylvester left Colombia.85

Final accounting had revealed a drastic loss of $65,000 for the year 1930, calculated based on the actual costs of operations reduced by emerald sales worth only $48,000.86 Coupled with the negative assessment in the recently prepared report by Gilles, the leaders of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation instructed Rainier to close the mine and to return to New York.87 As directed, Rainier traveled to New York in October 1931 for consultation with the mine owners,88 leaving his family at Las Cascadas.

According to Rainier in Green Fire, he returned to Colombia with preliminary permission from the company to continue mining operations at Chivor under his own responsibility.89 He went on to recount that with the help of Dixon and his sons, the men “bombed out” the bandits who had overtaken the mine during Rainier’s absence. Rainier and Dixon then collaborated in mining the deposit for a few months, but the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation soon withdrew its permission and sent new staff to run the mine. Rainier and Dixon had to hand over operations to the new leaders sent by the owners and leave Chivor. Yet according to Rainier, the new operators again lost control of the mine after a short period due to renewed hostilities from the bandits. Rainier’s account of this late 1931 to mid-1932 timeframe, however, has not been corroborated by independent evidence, and only the pre-October 1931 bandit fighting has been verified by the historical record.

81Peter W. Rainier, Jr., pers. comm. 2017 (“I moved to Chivor when I was two and my father was already there. I moved away from Chivor when I was four, so assume that the mine was shut down at that time. That was when my father started Las Cascadas.”). See also the interview of Peter W. Rainier Jr., by GIA staff, 2015, available at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/summer-2016-rainier-footsteps-journey-chivor-emerald-mine.

82File “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

83Interview of Peter W. Rainier, Jr., by GIA staff, 2015, available at https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/summer-2016-rainier-footsteps-journey-chivor-emerald-mine.

84Robert Elmer Sylvester was identified through assistance from Rebecca Toov, University of Minnesota Archives, pers. comm. 2018, and comparison with the photo of Sylvester, dated 1927, published in The Gopher, 40 (1927), p. 443 (electronic p. 463 at https://umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll339:27309/p16022coll339:27197).

85File Robert Sylvester, List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigration Officer at the Port of Arrival, New York, October 1931, MyHeritage.com. To the extent that Rainier (1942) is susceptible to an interpretation that would place the bandit fighting solely after October 1931, such is not supported by the historical record.

86Engineering and Mining Journal, 131 (1931), p. 485.

87Rainier, 1942.

88File Peter Rainier, List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigration Officer at the Port of Arrival, New York, October 1931, MyHeritage.com. The travel documentation gave Gachalá (interestingly not Chivor) as Rainier’s residence in Colombia and indicated that the purpose of the entry was to visit the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation for a planned stay of two months.

89Rainier, 1942.

In a report dated November 2, 1931, the United States Department of Commerce noted, “The Chivor emerald mine operated by American interests has been closed, owing to depressed prices.”90 It was subsequently reported that Chivor was closed again in October 1932,91 but no documentation detailing the mode of operation or the person(s) in charge of the mine in 1932 is available. Rainier remained in Colombia, working as a mining consultant, e.g., for the Colombian government at Muzo and Coscuez in 1933 and 1934.92 After the death of his wife Margaret in 1937, he left the country.93

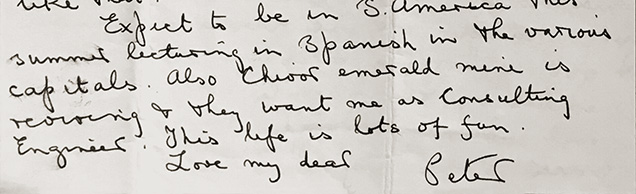

Rainier initially settled in Egypt for health reasons and then joined the British Eighth Army after the outbreak of World War II, serving from June 1940 to June 1943. During this period, Rainier was also engaged in writing several books, including Green Fire (1942), all in the genre of regaling readers with his adventures.94 Following his retirement from the British Army, Rainier traveled in the United States, lecturing about his escapades fighting in Africa during the war. Speaking engagements in South America were planned as well, and he even considered taking a position as a consulting engineer at Chivor when contacted in 1944 by the mine owners about a potential attempt to reopen (figure 15).95 Rainier died in a hotel fire in Ontario, Canada, in July 1945.96

90Commerce Reports, 4, No. 44 (1931), p. 247.

91Mineral Trade Notes, 2, No. 4 (1936), p. 18.

92Rainier, 1933a, 1933b; Minerals Yearbook (1934), pp. 1095–1096; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 70, No. 22562 (1934), p. 140. Certain of these projects were undertaken in cooperation with Christopher Dixon.

93Peter W. Rainier, Jr., pers. comm. 2017.

94Published works included African Hazard (1940), American Hazard (1942), and Pipeline to Battle: An Engineer’s Adventures with the British Army (1943). Additional book manuscripts remained unfinished. Letter by Peter Rainier, March 25, 1943, to his sister Priaulx Rainier, Priaulx Rainier collection, Royal Academy of Music, London.

95Letter by Peter Rainier, April 25, 1944, to his sister Priaulx Rainier, Priaulx Rainier collection, Royal Academy of Music, London.

96The New York Times, July 7, 1945.

CHIVOR IN DORMANCY AND TRANSITION (1932–1947)

Following closure of the mine, Chivor entered a period of dormancy from an operational standpoint, at least insofar as concerned official work on behalf of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation. Illegal mining and theft, however, remained a constant feature.97 The interest of the press and public decreased and was only revived briefly by the release of Green Fire in 1942.98

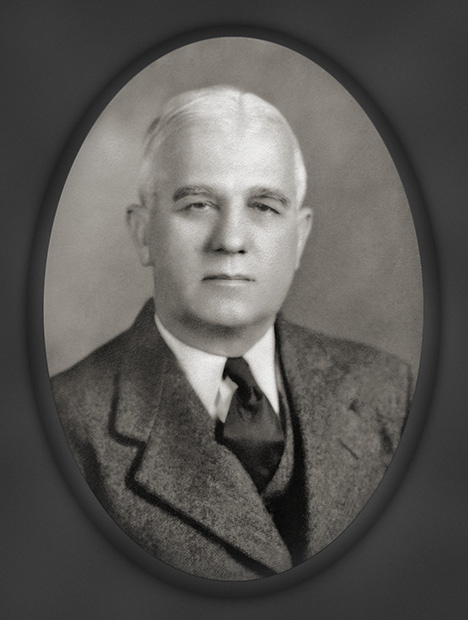

From a corporate and administrative perspective, documentation from the 1931 to 1932 period reflected that MacNamara remained president of the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation and that directors at the time included MacNamara, the banker Robert E. Henry, and the attorney Francis Philip Pace (1876–1957, figure 16).99 On September 28, 1933, the name of the corporate entity was formally changed from Colombia Emerald Development Corporation to Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc.100 The name change was registered in Colombia in November 1934.101 Corporate headquarters continued to be in New York City, and company information under the new name was officially filed with the New York State, Department of State, Division of Corporations, on November 23, 1935.102 Subsequent documentation from 1936 to 1940 showed that Henry was by then serving as president and Pace as secretary and/or treasurer.103

In a renewed push to regain effective control, a national police squadron was dispatched to Chivor in 1936 to secure the mine pursuant to a contract between the government and Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc.104 As a result, after several relatively quiet years with respect to mine operations, the mine was able to be leased from 1937 to 1940 (or even later) to the Compañía de Esmeraldas de Colombia, which employed about 100 workers.105 In January 1941, the mine was being operated with Ernesto Fernández as the mine administrator.106

Nonetheless, by 1943 the outlook of company leadership was not optimistic, with the financial press reporting: “Mr. Francis P. Pace, an attorney and treasurer of the company informed us on Oct. 29, 1943, that he has served the company for the last five years, and has received nothing for his services. He stated that he is the biggest stockholder and biggest creditor of the company. Mr. Pace considers the stock worthless.”107 Later, as a consequence of the economic and political situation engendered by World War II, the mine again became inoperative until 1947,108 with the exception of the ever-resilient illegal and uncontrolled mining, and even gun fighting, at the unguarded site.109 Although the possibility of reopening may have been broached during the interim, such as by contacting Rainier in 1944 (again, see figure 15), such efforts went nowhere. After Walter J. Cowan served as corporate president in the early to mid-1940s,110 Pace took over that position in 1947.111

97Diario Oficial (Colombia), 69, No. 22208 (1933), p. 353.

98Rainier, 1942; The Ottawa Journal, November 28, 1942, p. 21. Peter Rainier’s story also provided the basis for a novel written by the Colombian author Torres Neira in 1967, using fictional characters styled after the real players (e.g., Rainer became Garnier).

99Poor’s Financial Records, Industrial Manual, New York (1931), p. 788; Poor’s Register of Directors of the United States and Canada (1932), p. 257. Francis Philip Pace was born in Canada and moved with his parents to Buffalo, New York, in 1880. Pace was naturalized in 1890. Although his father was a stone cutter, Pace studied law and received a degree from the New York University School of Law. He went on to work in New York as a lawyer and was involved with multiple corporate boards. In his engagement with the Colombia Emerald Development Corporation and, after its renaming, Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., Pace was supported for several years by his son Brice Pace (1915–2001), who held a degree in geology from New York University and sought to assist his father and the company as a member of the board of directors in the late 1930s. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880; The Albany Law Journal, 59 (1899), p. 484; New York Herald, August 5, 1916, p. 8; Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920; Gregory, 1995.

100State of Delaware, Department of State, Division of Corporations, Entity Details; The Morning News, September 29, 1933, p. 23; The News Journal, September 29, 1933, p. 29.

101Escritura 2045, November 17, 1934, Notaria 1, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

102New York State Department of State, Division of Corporations, Entity Information.

103The Newark Post, November 26, 1936, p. 2; Who’s Who in New York City and State, 10 (1938), p. 599; Poor’s Register of Directors and Executives, United States and Canada (1940), p. 960.

104Diario Oficial (Colombia), 72, No. 23219 (1936), pp. 697–698.

105Minerals Yearbook (1938), p. 1295; Minerals Yearbook (1939), p. 1393; Minerals Yearbook (1940), p. 1461; Minerals Yearbook (1941), p. 1409; Las Industrias Mineras y Manufactureras en Colombia, translation of Mining and Manufacturing Industries, United States Tariff Commission, Publication TC-250 (1949), pp. 30–31.

106File “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

107Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities (1944), p. 147.

108Minerals Yearbook (1949), p. 1579.

109Mineral Trade Notes, 25, No. 2 (1947), pp. 28–29; Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 72 (1952), pp. 282–290.

110Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities, 11 (1946), p. 149; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26422 (1947), pp. 454–456.

111Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26422 (1947), pp. 454–456; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26436 (1947), p. 657; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26672 (1948), p. 1132; Morello, 1956; Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 97 (1961), pp. 138–145.

CHIVOR UNDER RENEWED OPERATIONS (1947–1951)

After the hostilities of World War II drew to a close, the Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., leadership endeavored to restart active mining operations. Pace always hoped that it would be possible to turn Chivor into a profitable mining site.112 In service of that aim, and to address creditor issues, he traveled to Colombia at least three times, in 1947, 1948, and 1950.113 Operational control in Colombia was placed under a series of managers. James W. Raisbeck Jr., an American, began in July 1947,114 and was succeeded by Luis Salómon, an American, and Jacques Meyer, a German, in December 1947.115 Because of the limited funds available, the latter two instigated a contractor system under which contracted foremen hired and paid their own laborers.116 Salómon and Meyer were replaced by Eric G. Ramsay and Antonio C. Cosme, both United States citizens, in July 1950.117

Additional investment and involvement from Colombian parties had also been brought on board by 1950, as reported in the trade press:118

Present-day exploitation of the emerald deposits is directed by the two largest stockholders in the corporation, one of whom [Pace] has had many years’ association with the firm and whose ceaseless efforts have salvaged a defunct corporation, with more or less worthless stock, and has placed it back into production, with the possibilities steadily increasing that the stockholders will at last begin to realize some return on their investment. The other of those two men [identity unknown to the authors] is a well-known Bogotá, Colombia, importer and exporter, who is in charge of the operations in Colombia. This man has himself invested large sums of money in the property, and, in his position on the spot, has been able to supervise the mining, appraisal, registration, and exportation of the gem stones.

Such efforts resulted in production of 5,400 carats in 1947, with yields increasing to 82,370 carats in 1948 and 91,656 carats in 1949.119 Although operations were impacted in late 1948 due to rioting and theft by local workers, the situation was brought under control after the company sent Carl (Carmine) Cavallo, an American civilian construction superintendent, to Colombia to restore order at the mine.120

For a period extending approximately from the first to the third quarter of 1950, the New York owners employed American gem hunter Anderton (figure 17) to manage on-site operations at the mine. Anderton had just returned from gemstone ventures in Sri Lanka, having left Colombo on October 25, 1949, and having arrived in New York on November 21.121

112Scott Pace (grandson of Francis Phillip Pace), pers. comm. 2018.

113File Francis P. Pace, Passenger Manifests of Airplanes Arriving at Miami, Florida, November 1947 and April 1948, Ancestry.com; Escritura 2204, July 12, 1950, Notaria 3a, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia); Diario Oficial (Colombia), 87, No. 27372 (1950), pp. 367–368.

114Escritura 1353, April 28, 1947, Notaria 3a, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia); Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26422 (1947), pp. 454–456; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26436 (1947), p. 657.

115Escritura 4313, December 17, 1947, Notaria 3a, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia); Diario Oficial (Colombia), 83, No. 26672 (1948), p. 1132.

116Wehrle, 1980.

117Escritura 2204, July 12, 1950, Notaria 3a, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia); Diario Oficial (Colombia), 87, No. 27372 (1950), pp. 367–368.

118Mineral Trade Notes, 30, No. 1 (1950), pp. 29–38.

119Minerals Yearbook (1949), p. 1579; Mineral Trade Notes, 31, No. 1 (1950), pp. 31–32; Minerals Yearbook (1951), p. 551; Minerals Yearbook (1953), p. 556.

120Tampa Bay Times, December 22, 1952, p. 5. Carl (Carmine) Cavallo apparently remained involved at Chivor in some capacity during periods in 1951 and 1952, but details of his role are vague. See also File Carmine Cavallo, Manifesto de Pasajeros, Flight Bogotá – New York, December 21, 1951, MyHeritage.com.

121File Russell Anderton, List or Manifest of aliens employed on the vessel as members of crew, November 1949, MyHeritage.com.

During Anderton’s tenure, mining methods differed from the practices under Klein and Rainier. According to Anderton,122 terraces were cut into the hillside only to the extent necessary to reveal the structures beneath the overgrowth. If promising veins were found, they were pursued exclusively by tunneling. The actual mining was still accomplished through the contractor system, with foreman hiring and paying their own laborers. The contractors identified the target areas they wished to tunnel and, upon approval from management, would organize the work. The emeralds found were (theoretically) turned over to the mine administration, and the contractors received half the stones’ value as compensation. Thievery, however, was rampant with this system.

Reported yield for 1950 amounted only to 7,177 carats,123 and by late in the year tensions had arisen between the American and Colombian associates. As Anderton described in a report published in the winter of 1950–1951: “At the present writing Chivor, for all practical purposes, is closed.... The year was marked by a bitter struggle between the Colombian interests and the New York officers for control of the mine, a situation prevailing at the moment.”124 By that point, in the midst of the mounting difficulties, Anderton had been dismissed from his management role at Chivor.125

In the last months of 1950 and the first months of 1951, the dispute between the American and Colombian associates had intensified to the point that trade press reported: “The American group sent down a general representative to take charge of the operations. However matters became worse instead of improving, and subsequently chaos and complete lawlessness reigned the mine.”126 The company was also in dire financial straits, owing more than 700,000 pesos (equivalent to about US$280,000), and creditors had filed lawsuits. In August 1951, Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., hired John M. McGrath to negotiate a financial settlement with the United States and Colombian creditors, but no resolution was achieved. Attempts by the American mine owners to sell the mine to the Colombian government were rejected as well.127 Instead, the turmoil culminated by February 1952 in insolvency proceedings (concurso de acreedores) in civil court in Bogotá.128 Efforts to sell the mine to the government were also reprised after the proceedings commenced, but the offers were rebuffed once again.

During the tumultuous period surrounding the insolvency, the entity apparently suspended mining operations from an official standpoint. Nonetheless, workers resumed some production in 1951, but all stones went into the black market.129 With a degree of irony, a trade publication commented: “Despite this trouble, it was reported that a new vein was found at Chivor, and the emeralds produced were said to be the best quality ever taken from the mine.”130

122Anderton, 1950–1951. See also Lentz, 1951; Spence, 1958a, 1958b.

123Mineral Trade Notes, 33, No. 3 (1951), p. 36; Mineral Trade Notes, 35, No. 1 (1952), p. 35.

124Anderton, 1950–1951.

125The byline for the Anderton (1950–1951) article identified the author as “formerly Manager of Mines at Chivor,” thus indicating a term that had ended by the winter 1950–1951 quarter.

126Mineral Trade Notes, 35, No. 1 (1952), p. 35.

127Domínguez, 1965.

128Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso de 1960 (1960), pp. 20–21; Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 97 (1961), pp. 138–145; Domínguez, 1965. The American mine owners were represented in Bogotá by Mauricio Makenzie.

129Mineral Trade Notes, 35, No. 1 (1952), p. 35; Minerals Yearbook (1955), p. 440.

130Minerals Yearbook (1954), p. 611.

CHIVOR UNDER RECEIVERSHIP (1952–1970)

Once the insolvency proceedings had been instigated, Chivor operated under receivership.131 The historical record is unclear as to who first filled the role of receiver (síndico secuestre or síndico de concurso), and details of the legal parameters governing the interaction between the receiver and company personnel are equally obscure. Anderton, however, did apparently return to the mine in a management capacity in 1952 to 1953, after writing Tic-Polonga.132 American press noted in 1952 that “Anderton is in New York now and plans to return to South America soon in another effort to control and operate these Mines.”133 After that brief period, Anderton turned his attention to other prospecting and mining ventures in the Chivor and Gachalá regions. He remained in Colombia, but he gradually moved from mining operations to the gem trade in Bogotá.134

From January 1955 to the end of September 1957, the position of receiver of Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., in Bogotá was held by Walter de Freitas,135 a Brazilian lawyer.136 He was assisted by the Swiss mineralogist Dr. Jean (Juan) Stouvenel.137 The mine inspector for Chivor throughout this period was Pedro Patiño Patiño (figure 18).138 As receiver, Freitas’s directive was to utilize company property for the benefit of creditors. Late in his term, however, he engaged in a transaction that would become mired in legal controversy. Freitas sold a portion of the emerald production near the end of September 1957 to Walter Maurer, a German gem merchant. A subsequent lawsuit questioned whether the sale had been properly conducted before his final day in office, while he was still authorized as receiver to dispose of company assets on behalf of creditors. The Corte Suprema de Justicia ultimately ruled in August 1961 that the transaction took place before Freitas left the position at the close of September 1957, and the decision cleared him of wrongdoing.139

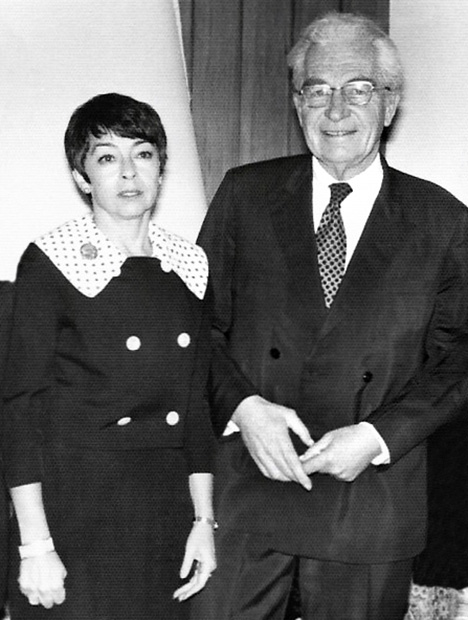

In October 1957, Freitas was succeeded by American Willis Frederick Bronkie (1912–1979, figure 19).140 Bronkie filled dual roles as mining engineer over Chivor operations and receiver of Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc. One week after he took office, on October 8, 1957, Bronkie dismissed Patiño.141 Earlier that year, in February 1957, Pace had died, and records regarding the corporate leadership in New York become somewhat disjointed from that point. New York investment banker Oliver John Troster (1894–1976) served as a director and secretary from 1957,142 and by the very early 1960s (or even earlier than that), George Daniel Besler (1902–1994, figure 20)143 of New York had stepped in as president of the company.144

131Anderton, 1955, 1957.

132Anderton, 1965.

133The Tennessean, November 9, 1952, p. 21.

134Manuel J. Marcial de Gomar, pers. comm. 2017. Marcial de Gomar, a Florida-based jeweler, began working with Russell W. Anderton in Colombia in 1955 as an interpreter, and their cooperation continued in Anderton’s later enterprises.

135Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 103–104 (1963), pp. 313–327.

136Walter de Freitas studied law at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and received a degree in 1948. His ensuing career path saw him both working as a mining attorney and serving as an editor for the Jurisprudência Mineira, a Brazilian publication focused on the mining industry and prepared under the auspices of the judiciary in Minas Gerais.

137Martínez Fontes and Parodiz, 1949; Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 103–104 (1963), pp. 313–327.

138Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 127 (1968), pp. 5–8.

139Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 103–104 (1963), pp. 313–327.

140Ibid.

141Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 127 (1968), pp. 5–8. Pedro Patiño Patiño later challenged in a lawsuit whether he had been paid correctly.

142World Who’s Who in Commerce and Industry, 15th ed., 1967, published 1968/69, p. 1391; Who’s Who in Finance and Industry, 16th ed., 1969, published 1970/71, p. 703; Standard & Poor’s Register of Corporations, Directors and Executives, 2 (1975), p. 1426; The New York Times, October 5, 1976. Oliver John Troster had been a partner in the New York–based company Troster, Singer & Co. since 1920, and he apparently remained involved with Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., until at least 1975.

143George Daniel Besler was the son of William George Besler (1865–1942), the general manager and president of the Central Railroad of New Jersey. George Daniel Besler received a degree in geology from Princeton University in 1926, but his subsequent career focused on industrial technology. He worked for the locomotive firm Davenport-Besler Corporation, and in the 1930s he and his brother William John Besler (1904–1985) developed high-pressure steam-powered engines for cars, locomotives, and the world’s first steam-driven airplane. Throughout his life, Besler held roles in several companies. Family members recall that he was president of the company that owned the Chivor emerald mine in Colombia in the 1960s. Who’s Who in Commerce and Industry, International Edition, 9 (1955), p. 99; Myers, 2000; Lynn G. Stewart, pers. comm. 2018.

144Renata de Jara, pers. comm. 2018. Renata de Jara served as Willis Frederick Bronkie’s secretary, typing and translating letters, and she recalls typing correspondence from Bronkie to George Daniel Besler as president from 1960 or 1961 onward. See also The National Observer, February 19, 1968, p. 8, which refers to George Besler as the president of Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc.

At the outset of his term, Bronkie faced substantial indebtedness to both Colombian and American creditors, as set forth in an accounting by the Corte Suprema de Justicia in 1961.145 At that time, the Chivor mine was still accessible primarily by a one-day journey on horseback from Guateque, but a road to the mine from the towns Chivor and Almeida was constructed during Bronkie’s tenure.146

At the beginning, mining under Bronkie continued to employ the system of contractors who hired and paid their own local workers.147 One inspector for each tunnel would be on the company’s payroll. The practice of using modern equipment such as an automatic compressor or bulldozers to remove the overburden, which had begun before he took office, was also continued.148 Initially, work proceeded through simultaneous use of both step-cut terracing (i.e., an open-pit technique) and tunneling (i.e., an underground method following the emerald veins).149 Step-cut terracing would be particularly useful in steep areas where a bulldozer was unable to operate. Tunneling work in the late 1950s involved eight separately named areas, each with a length of up to about 100 meters. For example, in April 1958, 96 men and nine contractors were working in two tunnel areas, one of which yielded gemstones worth over $100,000 from approximately two meters of the emerald-bearing vein.150 However, no new tunnels were dug, and from the mid-1960s to the end of the decade, exclusively open-pit work was performed.151

During that mid-1960s period, 125 miners were employed at Chivor,152 with a Spanish mine administrator, Evaristo Muñoz.153 Regardless of the methods used, success was extremely sporadic—mining could go on for months without production of a single emerald crystal of facetable quality.154 The value of the emerald yield fluctuated on a yearly basis from as high as $2,000,000 to as low as $200,000.155 In those years, the Colombian government oversaw the receivership and production largely through the inspector (Interventor de Salinas y Esmeraldas), Rafael A. Domínguez.156

Bronkie, as both receiver of the company and mining engineer for Chivor, worked alternately in the office in Bogotá and at the mine. He employed Alfredo Sierra as his so-called second in command and bodyguard. Life in that era was notoriously dangerous, and once Bronkie was even shot in the back at his house in Bogotá.157

145Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 97 (1961), pp. 138–145.

146Gonzalo Jara, pers. comm. 2018. In addition to improved physical access, Willis Frederick Bronkie apparently also sought to augment communications. He was represented in negotiations with the government for a radio transmission license by the Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc.’s legal agent in Colombia, Hernando Uribe Culla. Diario Oficial (Colombia), 98, No. 30571 (1961), p. 286; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 102, No. 31888 (1966), p. 495.

147Johnson, 1959, 1961.

148Anderton, 1957; Johnson, 1959, 1961.

149Johnson, 1959, 1961.

150 In the late 1950s, the Colombian government also named several individuals Inspector of Emeralds in Chivor (Inspector de Esmeraldas en Chivor), always under renewable three-month contracts. Diario Oficial (Colombia), 97, No. 30240 (1960), p. 581; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 97, No. 30275 (1960), p. 116.

151Gonzalo Jara, pers. comm. 2018.

152Anderton, 1965.

153Alfonso Montenegro, pers. comm. 2018. Alfonso Montenegro, a miner, began working at Chivor in 1955 under Walter de Freitas, and he continued to serve under Willis Frederick Bronkie and mine administrator Evaristo Muñoz.

154The National Observer, February 19, 1968, p. 8.

155Cochrane, 1970.

156Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso de 1961 (1961), pp. 305–308; Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso de 1963 (1963), pp. 28–31; Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso de 1964 (1964), pp. 212–214; Memoria del Ministro de Minas y Petróleos al Congreso de 1965 (1966), pp. 195–197.

157The Morning Herald, April 14, 1964, p. 3; Renata de Jara, Gonzalo Jara, and Robert E. Friedemann, pers. comms. 2018.

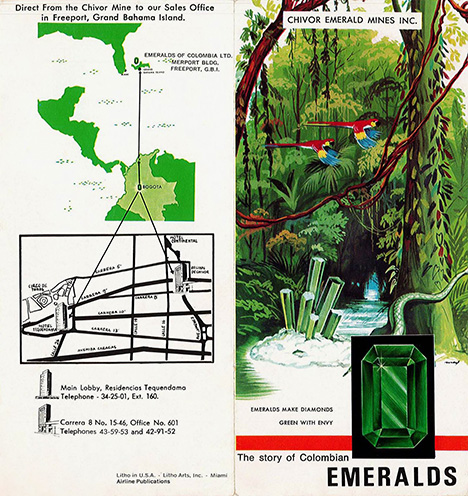

Between 1963 and 1968, Bronkie’s business approach gradually transitioned from solely emerald mining to additional related enterprises. The broader focus incorporated dealing in and selling rough (figure 21) and cut (figure 22) stones to international buyers as well as opening jewelry shops (e.g., in Bogotá, Cartagena, Panama, Miami, and the Bahamas, figure 23).158 The increased need for rough and especially cut emeralds to supply the jewelry stores was satisfied by purchasing rough and even faceted stones on the open market in Bogotá. As the 1960s drew to a close, the merchandising and retail business had overtaken the Chivor mining operations in prominence for the company.159 By the end of the decade, the mine employed only 25 workers.160

Given the reduced contribution from mining to the company’s revenue-generating capacity, the leadership in New York began to contemplate “new methods to accelerate production.”161 Specifically, in 1968 the press reported that Besler, as the company’s president, had “sent an engineer to Bogota recently to convince Mr. Bronkie of the need to abandon eventually the laborious hand-picking method for a blasting-bulldozing operation that would increase the daily soil turnover by tenfold.”162 Besler was quoted as saying: “After the receivership ends, we hope things will move along on a more progressive basis.”163

The latter point, i.e., the end of the receivership, was apparently becoming a realistic possibility. The 1968 article noted that Bronkie had “paid the debts that forced the company into receivership 17 years ago” and that he expected “soon to file documents, asking a Colombian court to end the receivership, returning control to the company’s 3,000 American stockholders.”164 It was anticipated that when the receivership ended, Bronkie would turn over control to a company representative recently sent to Colombia from New York.165

That anticipation came to fruition two years later. In 1970, the Colombian court overseeing the insolvency proceedings ruled that the company’s liabilities, aggregating $330,000, had been satisfied. The receivership was lifted, and control of Chivor Emerald Mines, Inc., was returned to the entity’s New York officials.166 As of the year of the transition, Bronkie had been replaced by Richard S. Pastore, an American lawyer, as the final receiver; the Colombian attorney Luis E. Torres was representing the company; Noel R. Merriam, a United States citizen, was serving as general manager in Bogotá; and the Colombian Jose Rodriguez was filling the role of mine manager.167 In terms of market value at that juncture, the stock was traded over the counter at 50 cents per share in 1970.168 During his years in office, Bronkie had been paid, at least partly, in shares of the company, thereby becoming one of the larger shareholders.

158The National Observer, February 19, 1968, p. 8; Renata de Jara, pers. comm. 2018; Marcial, 2018.

159Renata de Jara, pers. comm. 2018.

160Robert E. Friedemann, pers. comm. 2018.

161The National Observer, February 19, 1968, p. 8.

162Ibid.

163Ibid.

164Ibid.

165Ibid.

166The New York Times, May 16, 1970; Cochrane, 1970; Feininger, 1970.

167Bancroft, 1971; Diario Oficial (Colombia), 108, No. 33382 (1971), p. 519; Gaceta Judicial (Colombia), 146 (1973), pp. 406–407.

168The National Monthly Stock Summary, 117 (1970), p. 228.

CHIVOR POST-RECEIVERSHIP (1970–PRESENT)

With the termination of the receivership, the New York leadership regained control over mining operations at Chivor, and in 1971 the American management requested an inspector from the Colombian government to check the emerald production.169 However, the Americans would soon step away from the Colombian emerald venture. Although the record as to details is beyond the scope of this study, Chivor was sold by Bronkie and/or the New York–based company representing the American shareholders in the early 1970s through a series of transactions.170 Chivor was gradually taken over by Colombian interests.171

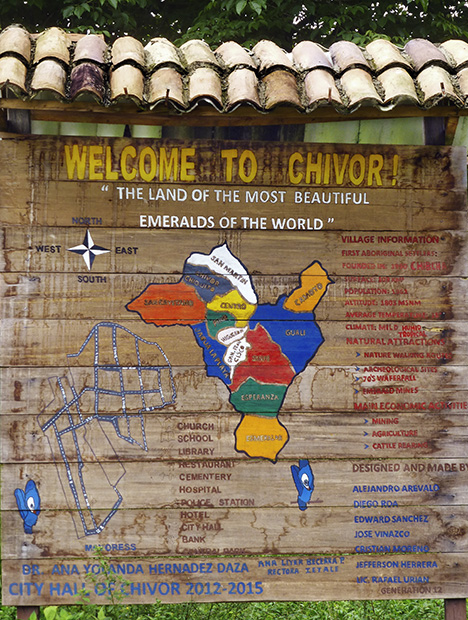

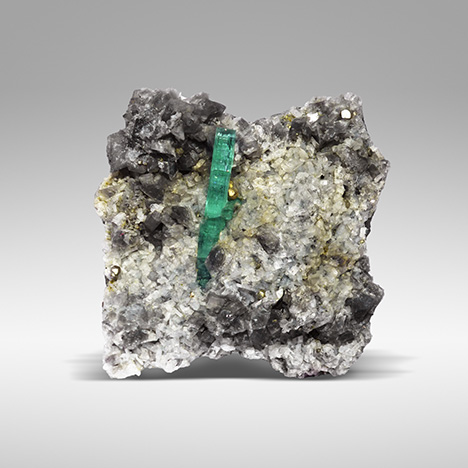

At present, the principal mines in the Chivor area are operated by two companies, Soescol Ltda. and San Francisco C.I.S.A., and/or their controlling shareholders Uvaldo Montenegro and Hernando Sánchez, respectively.172 Chivor is worked exclusively underground by tunneling, and open-pit emerald mining in the steep mountain range is no longer performed (figures 24 and 25). Currently, these primary operators are working numerous tunnels or mines on the different existing concessions—including San Pedro, San Gregorio, Manantial, Oriente, Piedra Chulo, Quebra Negra, Gualí, Dixon, and Tesoro.173 Additional galleries known within the region are Gavilanes, San Judas, El Acuario, Mirador, Milenio, Porvenir, Palo Arañado, Calichal, Camoyo, Klein & Cuatro, Gualí, and El Pulpito. In the town of Chivor (figure 26), there is a small informal street market for faceted stones, specimens in matrix (figure 27), and rough emerald crystals (figure 28).

LEGENDS AND REALITY: RAINIER, ANDERTON, AND THE HISTORICAL RECORD

The view of Chivor’s story from 1924 to 1970 has to date been largely guided by the accounts penned by Rainier and Anderton in Green Fire and Tic-Polonga, respectively. Both of those publications, however, are marked by notable absences. For instance, Rainier never mentioned the involvement of the corporate leadership in New York in the stock market manipulation controversy (Lewisohn, MacNamara, Rice), nor did he name either his predecessors in mine management (Burns, Mentzel) or his assistants in the work at Chivor (Gilles, Sylvester). Conversely, he dedicated a full chapter of his book to “Joaquin the Bandit,” a character apparently inspired by Joaquín Daza with whom he was involved in a legal dispute. Yet Rainier’s recitation contrasts strongly with the detailed record found in the Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia) in Bogotá,174 signaling an intent to offer an adventurous tale as opposed to an entirely factual text. Thus, a comparison of Rainier’s narration in Green Fire with original documents preserved from the period shows that the book employed real events to establish a rough framework but that details were supplemented, embellished, and even rearranged chronologically to suit the genre. More mundane matters such as the facts from the late 1920s that led to his engagement by the mine owners and the colleagues cooperating at Chivor were omitted. With Anderton, the lack of nearly any dates to frame the events is particularly glaring. The difficulties are compounded by the fact that an untold number of individuals involved in administering or operating the mine from New York, Bogotá, or Chivor itself left few, if any, traces in publications or official records.

169Latin America, 5 (1971), p. 123.

170Gonzalo Jara, pers. comms. 2017, 2018.

171Keller, 1981; Erazo Heufelder, 2005; Cepeda and Giraldo, 2012.

172Fortaleché et al., 2017.

173Ibid.

174File “Joaquín Daza B.,” Volume “Propuestas Minas 99,” Ministerio de Industrias, Departamento de Minas y Petróleos, Archivo General de la Nación (Colombia).

Nonetheless, by using independent contemporaneous materials in combination with and in restraint of the dramatized accounts, it has become possible to outline a more verifiable chronology of the period. The almost half-century in which Chivor was mainly owned and operated by the same American company saw numerous ups and downs in terms of productivity, emphasis, and financial fortunes.

In the first years after 1924, profit for the principal shareholders, in close cooperation with Rice, derived primarily from the United States stock market. Mining activities were comparatively minimal, and public interest centered on the scandals implicating company leaders Lewisohn and MacNamara. Then, under Rainer’s mine management from the late 1920s into the beginning of the following decade, the situation shifted to a greater focus on the operational side. Before long, however, the scenario reversed again, with Chivor being closed and the company essentially withdrawing from operating the property to any significant degree until after World War II.

Yet another about-face in the late 1940s to early 1950s brought renewed operational efforts instigated by Pace on behalf of the company in New York and headed by Anderton at the mine. That era of productivity nonetheless shortly fell victim to controversy between American and Colombian associates and mounting debts. The result was insolvency proceedings instigated under Colombian law in 1952 and nearly two decades under receivership. Bronkie, as receiver and mining engineer, was eventually able to restore a measure of financial health, and the receivership was lifted in 1970.

The American shareholders thereby regained full control over the mine, but within a few years, Chivor was sold, closing an era and paving the way for the increased local control and productivity existing today. While countless details remain fraught with mystery, particularly insofar as concerns the motivations incentivizing various decisions and any comprehensive accounting of mining costs versus emerald sales, the tale of Chivor, even as presently known, likely has few equals. One thing that is clear, however, is that Prof. Robert Scheibe’s conclusion in September 1914 upon examining the mine’s potential—positing a realistic “chance” for a successful venture but also an extremely high “risk” in buying the property—proved a prescient one.

.jpg)