Cat’s-Eye Opal

Precious opal characteristically shows a spectacular play-of-color effect and may also display cat’s-eye or star phenomena produced by the internal structure (e.g., Winter 1990 Gem News, p. 304; Spring 2003 Lab Notes, pp. 43–44; Summer 2014 Lab Notes, pp. 152–153). Chatoyancy and asterism in opal are quite rare, however, because opal is a hydrated silica and has no repeating crystal lattice (J.V. Sanders, “The structure of star opals,” Acta Crystallographica, Vol. A32, 1976, pp. 334–338). The keys to creating and maximizing chatoyancy in opal is careful arrangement of the play-of-color patches, orienting the “brushstrokes” (stripe structure caused by misalignment of the tiny silica spheres producing play-of-color), and good cutting.

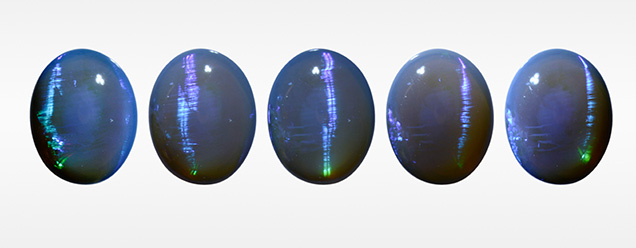

Recently, GIA’s Tokyo laboratory had an opportunity to examine a transparent double cabochon measuring 12.65 × 10.06 × 5.70 mm and weighing 3.79 ct. It showed blue to green play-of-color against a gray background as well as a distinct chatoyancy (figure 1). Standard gemological testing gave a specific gravity of 2.13 and a spot RI reading at 1.45, suggesting that the stone was opal. The brushstroke pattern within play-of-color patches and the strong bluish white fluorescence and phosphorescence after exposure to ultraviolet light were consistent with a natural origin. Advanced testing using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) also indicated that this was natural opal with no evidence of polymer impregnation and/or sugar treatment (G. Brown, “Treated Andamooka matrix opal,” Summer 1991 G&G, pp. 100–106). This opal had no synthetic features such as “snake skin” and “columnar structure” in any direction. There was no evidence that this stone was assembled.

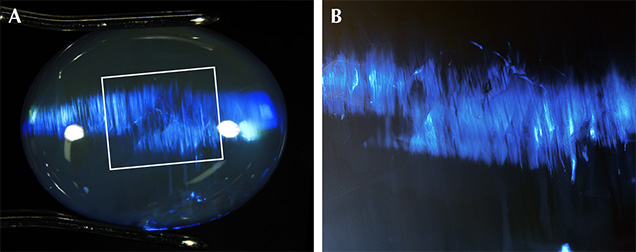

In microscopic observation, this opal contained several large blue to green play-of-color patches with parallel brushstroke patterns. The brushstrokes in each patch were mostly perpendicular to the length of the stone and parallel to each other, and the light reflection from the pattern created a distinct chatoyant effect (figure 2). Because the opal was composed of large blue dominant play-of-color patches, the parallel brushstrokes and the high-dome cabochon shape produced a distinct chatoyancy against the gray background. This was a striking example of cat’s-eye precious opal.

.jpg)