Fine Gems and Update from Myanmar

At the AGTA GemFair, Edward Boehm (RareSource, Chattanooga, Tennessee) showed us a succession of top-quality gems. Boehm is a geologist, gemologist, and accomplished gem dealer who works with rare and higher-end gems. He noted that the price of spinel from Myanmar has increased dramatically, with recent prices at the source more than double those of previous years. He explained that spinel has gained favor in Myanmar, which is reflected by the higher prices at this year’s show.

Boehm noted that a growing appreciation for spinel from all sources is driving higher market prices. As an example, he showed us a beautiful oval 21.56 ct Sri Lankan pink spinel cut to make the most of the gem’s high clarity and moderate dispersion. The size, clarity, and brightness are reminiscent of Tajik spinel. He compared this bright lilac pink Sri Lankan spinel with a strong orangy red square cushion-cut 9.82 ct Burmese gem, which he described as having a “flame” color. The per-carat price of the flame-colored Burmese stone is almost double that of the Sri Lankan spinel—$12,000 per carat wholesale versus $7,000 per ct. A strong red “flame” color makes the price jump significantly. If the stone were above 10 ct, Boehm added, the price would further jump to around $15,000 per carat.

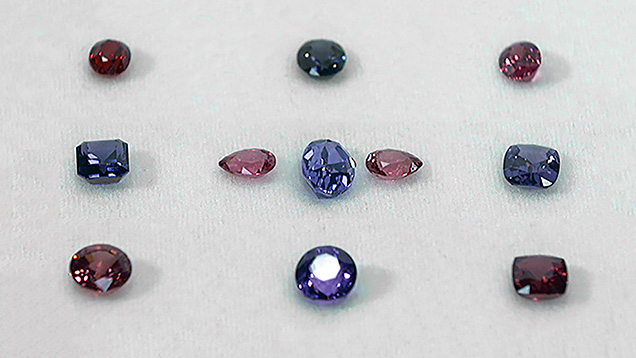

Pastel blue to violet spinels are also selling well for Boehm. Designers like to mix these delicate blues with pinks or “rose” colors of similar tone and saturation to produce very attractive suites and sets. The pinks help to highlight the violet or purple in the pale blues, he added. The bluish violet examples he showed us hailed from Sri Lanka and wholesaled for $1,200–$1,500 per ct (figure 1). Complementary rose-colored gems came from a variety of sources—including Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar—and ranged from $1,000 to $1,800 per ct.

Boehm explained that the most sought-after color is the “electric” haüyne blue, which comes from Luc Yen, Vietnam, and is only sporadically available in small sizes. He added that the light-toned, gray-to-violet blue colors are more available than in the past—partly because there’s more demand so more people are bringing it to market.

Like Burmese spinel, Burmese peridot is currently in vogue. Boehm showed us a fine 20.41 ct cushion-cut gem (figure 2). The presence of a multitude of tiny inclusions lend it a softness and reduce extinction. By comparison, fine Pakistani peridot—which is also available in large sizes—has a more “crystalline” appearance and deeper color, but shows more extinction. He explained that the price of Burmese peridot has recently gone up sharply. A top gem like the one in figure 8, which would formerly have been in the $250–$350 per carat range, is now wholesaling for $450–500 carat and even up to $600 per carat. He cautioned buyers to check whether a stone shows doubling in the pavilion in the face-up position, which is considered less desirable. Buyers want to ensure the stone is oriented in such a way that doubling isn’t visible through the table.

Next, he showed us a rich green, 4.81 ct cushion-cut demantoid garnet from Russia, which contained a golden-colored horsetail inclusion. Such a gem would wholesale for $15,000 per ct, he said. According to Boehm, gems of such pure green color rarely come out of the ground—they are typically heated to this color. This treatment has been going on for 10–15 years, he explained. Despite this treatment, the demantoid is still an exceptional stone.

Boehm explained that judicious heating converts a yellowish green gem to a vibrant green but removes some of the stone’s characteristic fire, making it an almost “electric” green color. He prefers a balance of color and fire, acknowledging that the gem’s inherent fire—flashes of red and blue coming off a green bodycolor—is part of its unique appeal. In today’s market, any demantoid over 2 ct is extremely rare, so this gem’s size of almost 5 ct makes it very desirable.

The demantoid was from new production rather than the secondary market, Boehm explained. He added that there is still newly mined supply and treaters are perfecting heating techniques to make gems much more vivid, although not all respond like this one.

Finally, he showed us a striking 31.79 ct Sri Lankan pear-shaped sapphire with padparadscha color—a delicate pink flushed with a bloom of orange (figure 3). He explained that the gem had been recut three times to perfect its shape and proportions. The objective of recutting the original old-style cut was to close the window on the pavilion, but any further work would affect the brilliance and might even lose the cherished pinkish orange color. He added that when cutting padparadscha sapphire, it is very hard to keep that balance of pink and orange, because sometimes the orange might be in just one portion of the stone, which could easily be removed accidentally. A gem of this size is enormous for a padparadscha, he noted, and the wholesale asking price would be in the neighborhood of $30,000–$35,000 per ct.

Boehm noted that on October 7, 2016, President Barack Obama signed an executive order lifting U.S. sanctions on Myanmar, allowing Burmese jadeite and rubies, and any jewelry containing them, to be imported into the United States. The sanctions had been imposed in 1997 (see https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/pages/burma.aspx).

Boehm felt fortunate to be in Mogok (figure 4) when the ban was lifted and was able to celebrate with many of the local miners and brokers. He hoped the change would significantly improve the supply of Mogok gems but anticipated that any increase in gems reaching the U.S. from this source would likely take some time. Most if not all Mogok mining licenses have been suspended as the Burmese parliament and ministries work together to rewrite mining laws in Mogok and the jade mining areas in Pagan. These laws have been in place for more than 100 years and have changed little.

When Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League of Democracy party won a majority of seats in parliament during the November 2015 election, it was able to effect change with a special focus on the environment. The new administration’s objective is to make reclamation integral to obtaining a mining or prospecting license, so that when mining finishes, the licensee will be obligated to return the land to its original condition. The government wants to ensure these laws are enforced and that environmental and ethical standards conform to Western expectations for the gem mining sector. The aim is for the new mining laws to meet the internationally accepted standards outlined by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of 34 democratic countries that develop economic and social policy to support free market economies. These principles are laid out in the policy paper OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252479-en). For more information on corporate social responsibilities and ethical colored stone supply chains, please see J. Archuleta, “The color of responsibility: Ethical issues and solutions in colored gemstones,” Summer 2016 G&G, pp. 144–160).

Boehm mentioned the recent AGTA October 2016 delegation (figure 5) to Myanmar that visited the cities of Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw, Mandalay, and Mogok. Along with other U.S. trade and industry bodies, AGTA is seeking to reestablish responsible gemstone trade between the two countries. This is only possible because of the political and economic progress Myanmar has made in the past six years, but it also depends on Myanmar’s gemstone sector meeting international standards such as OECD’s guidelines.

The delegation, which included GIA researcher Dr. James Shigley and representatives from Jewelers of America, met with a cross section of stakeholders, including the U.S. ambassador, ministers and representatives of the Myanmar government, international and local organizations, trade associations, gem dealers and traders, and mine owners. They visited a number of gem markets and mines, including the Baw Maw mine (figure 6) and the Taung ruby and sapphire mine.

According to Boehm, the delegation was an impartial group sent to look at the situation “on the ground” in Myanmar, particularly in Mogok. He explained that it was an “eye-opening” experience and although conditions were much better than the group anticipated, there was room for improvement. The delegation made a series of observations that were set out in their white paper, Step by Step – Myanmar Gem Sector Emerges from Isolation and U.S. Sanctions, which is available from AGTA’s website at http://agta.org/info/docs/burmawhitepaper2016.pdf

Boehm indicated that Mogok was still beholden on the U.S. gem industry’s ongoing efforts to ensure that Myanmar’s government follows through with its promise to manage the gem sector properly and that the Burmese people benefit from the gems. He cautioned that a lot of mining licenses remain suspended. Therefore it’s very unlikely that U.S. businesses will see much production until these are reinstated, possibly in late 2017. He forecasts that the U.S. trade at large will have to wait at least another year before production appears in earnest. At that point, he expects many more U.S. buyers will travel to Mogok and competition for scarce goods will drive prices up, but at least the goods can be legally imported into the U.S. once more.

He reported that because of the government’s suspension of mining licenses, Mogok’s mines are currently closed again after a brief reopening. Boehm suspects several reasons for caution on the part of the authorities. Firstly, it would be very tempting for miners to produce as much material as possible now that dealers from the U.S. can legally buy gems in Mogok, so the government wants to buy time to regulate mining ethically to make sure the Burmese people are protected (figure 7). Secondly, they want to prevent large foreign investors from taking over the mining sector. Finally, there are some security issues with traveling the new road leading into Mogok at night, which the authorities want to correct before mining licenses are reinstated. Boehm considers these good signs that demonstrate the Myanmar government’s commitment to security and corporate social responsibility for the good of its citizens.

.jpg)