Metallic Core in a Natural Freshwater Pearl

Although cultured pearls dominate the freshwater pearl industry, the rarer natural freshwater pearls are still encountered during routine laboratory testing. The majority of these have been handed down through generations, and recent finds are limited due to heavy regulations in the mussel shelling industry and lower demand for mother-of-pearl. Recently, GIA’s Mumbai laboratory received for identification a white circled button-shaped nacreous pearl measuring 5.74 × 3.98 mm and weighing 0.97 ct (figure 1).

The pearl displayed circular bands on its upper portion with minor sub-surface-reaching cracks and a translucent nacreous layer with overlapping platelets of aragonite. The pearl showed a strong yellowish green reaction when exposed to X-ray fluorescence. Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence analysis conducted on two spots revealed manganese levels of 348 and 390 ppm and strontium levels of 470 and 694 ppm, respectively. The results of both analyses are characteristic of pearls from a freshwater environment. Under long-wave ultraviolet light, the pearl exhibited a moderate greenish yellow reaction, which is typical for unprocessed white pearls. White cultured freshwater pearls are routinely processed and show moderate to strong blue reactions under long-wave UV.

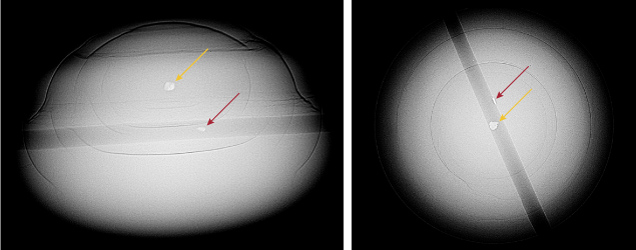

Real-time X-ray microradiography (RTX) imaging revealed a small near-round radiopaque white core, measuring approximately 0.20 × 0.15 × 0.12 mm, surrounded by concentric growth arcs extending to the pearl’s edge (figure 2). The core’s radiopacity suggested it was composed of a material of higher density than the surrounding nacreous area. This resembled the opacity typically observed in metals during X-ray radiography and was similar to metal cores previously noted in saltwater pearls (M.S. Krzemnicki, “Pearl with a strange metal core,” SSEF Facette, No. 24, 2018, p. 27; Summer 2023 Gem News International, pp. 244–246). Another metal remnant was observed in the pearl’s drill hole, initially presumed to be a fragment of a broken needle used during drilling (figure 2).

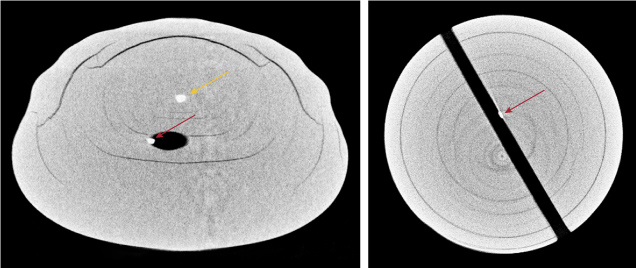

Upon closer examination using X-ray computed microtomography (μ-CT), the metal feature within the drill-hole area appeared similar to the metallic core found within the pearl and seemed to be partially embedded within the pearl’s growth arcs. Both metal features exhibited undulating outlines and a lack of sharp edges typically associated with a broken metal fragment. Given the similar properties of both metal features, the metal feature at the drill hole may have been present prior to the drilling process, rather than a remnant from a drilling needle (figure 3).

Because RTX and μ-CT imaging did not reveal any suspicious irregular linear or void structures typically found at the center of freshwater cultured pearls, the sample was identified as a natural freshwater pearl (K. Scarratt et al., “Characteristics of nuclei in Chinese freshwater cultured pearls,” Summer 2000 G&G, pp. 98–109). The structure present was comparable to that of natural freshwater pearls previously studied by GIA (Summer 2021 Gem News International, pp. 167–171). The only difference noted was the metallic core at the center of this pearl, a feature not commonly observed in natural freshwater pearls.

These observations suggest environmental contamination during the pearl’s formation, potentially due to the presence of a foreign object around which the pearl formed. The process of pearls forming around such foreign objects remains a topic of ongoing scientific research.

.jpg)