FTIR Observation on Sapphires Treated with Heat and Pressure

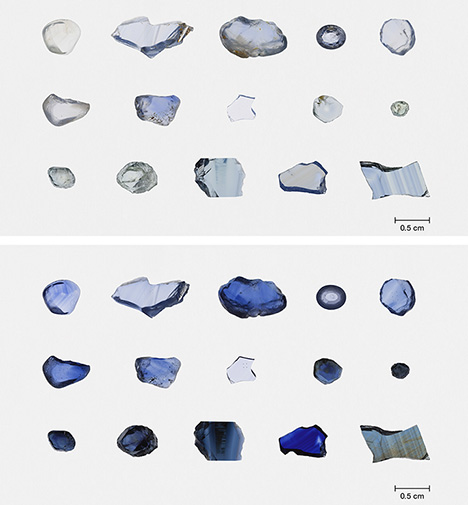

before (top) and after (bottom) heat with pressure treatment. Photos by Sasithorn

Engniwat.

Characteristics of sapphires heated with pressure have been discussed in several gemological publications in the past few years (e.g., M.S. Krzemnicki et al., “Sapphires heated with pressure – A research update,” InColor, Vol. 42, 2019, pp. 86–90). As previously reported, heat with pressure treatment is commonly applied to Sri Lankan sapphires, in either untreated geuda or conventionally heated blue sapphires, to enhance the blue color. The material has been treated at high temperature (approximately 1200–1800°C) with an application of pressure at nearly 1 kbar, using the facilities at HB Laboratory Co., Ltd. (H. Choi et al., “Sri Lankan sapphire enhanced by heat with pressure,” The Journal of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, Vol. 39, 2018, pp. 16–25).

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is considered a useful tool in revealing heat treatment of corundum (e.g., C.P. Smith, “A contribution to understanding the infrared spectra of rubies from Mong Hsu, Myanmar,” Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 24, 1995, pp. 321–335). Previous studies reported a great variability of FTIR spectra for sapphires heated with pressure, and FTIR spectra of this treated material generally showed a unique pattern of hydroxyl-related broad bands in the 2800–3500 cm–1 range, with the prominent position at around 3050 cm–1 (e.g., Krzemnicki et al., 2019). The origin of the resulting distinct IR broad bands has not been clearly determined. As discussed in Krzemnicki et al. (2019), broad bands centered at around 3050 cm–1 in sapphires heated with pressure share similar IR features observed in some acceptor-dominated corundum—heated or unheated natural materials, as well as laboratory-grown samples. (Acceptors refer to ions with the charge of –1 relative to the lattice, such as Mg2+ in corundum; see E.V. Dubinsky et al., “A quantitative description of the cause of color in corundum,” Spring 2020 G&G, pp. 2–28.)

According to a previous study (M.D.T. Phan, “Internal characteristics, chemical compounds and spectroscopy of sapphire as single crystals,” PhD dissertation, University of Johannes Gutenberg Mainz, 2015, https://d-nb.info/1075170532/34), iron (Fe3+) content in corundum can affect the position of the 3310 cm–1 IR peak. In sapphires heated with pressure, the starting material is generally limited to Sri Lankan stones. Since blue sapphires from Sri Lanka typically contain relatively low Fe concentrations (A.C. Palke et al., “Geographic origin determination of blue sapphires,” Winter 2019 G&G, pp. 536–579), the starting materials used in the study were expanded to various deposits, including Myanmar, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Montana, Australia, Nigeria, Cambodia, and Thailand, to cover a wide range of Fe contents presented in natural corundum (figure 1). The 36 untreated and 8 conventionally heated blue sapphires were treated using heat with pressure under the conditions reported in Choi et al. (2018). Their FTIR spectra and chemical analysis using laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) were measured in the same analysis area to observe whether there was any change in FTIR spectra for different amounts of Fe.

After heat with pressure treatment, the vast majority of treated sapphires in this study (>90%) showed essentially the same hydroxyl-related IR broad bands in the 2800–3500 cm–1 range with different prominent band positions at around 3050, 3130, or 3200 cm–1 (figure 2). The IR broad band centered at around 3050 cm–1 with related bands at ~3130 and ~3200 cm–1 (figure 2A) can be observed in sapphires heated with pressure that contained Fe <700 ppma (figure 3, circle), whereas IR broad bands with comparable band intensities at around 3050, 3130, and 3200 cm–1 (figure 2B) can be found in treated sapphires with 550–1350 ppma Fe (figure 3, triangle). At relatively high Fe concentrations (>900 ppma) (figure 3, square), the FTIR spectra of sapphires heated with pressure displayed IR broad bands with a prominent band position at around 3200 cm–1 (figure 2C). In the overlapped Fe range of the samples (500–700 ppma Fe and 900–1350 ppma Fe), different IR patterns could be obtained, possibly due to heterogeneity of the samples and different characteristics of analytical techniques—bulk analysis for FTIR and spot analysis for LA-ICP-MS.

This study shows other possible FTIR spectra patterns that might be observed in sapphires heated with pressure, as well as prominent IR bands of the treated material that can shift position with different Fe concentrations.

.jpg)