Manufactured Inclusions in Gem Materials

Inclusions in gems have gained popularity as social media has exposed collectors to a wide range of gem materials with interesting inclusions. As a result, there has been an increase in artificial inclusions in natural rock crystal quartz as predicted by E. Skalwold (Summer 2016 Micro-World, pp. 201–202). Recently, the authors had the opportunity to examine several unique gems with manufactured inclusions. Microscopic examination revealed that the main methods for manufacturing inclusions were carving, assembling, dyeing, three-dimensional internal laser engraving, or a combination of these methods.

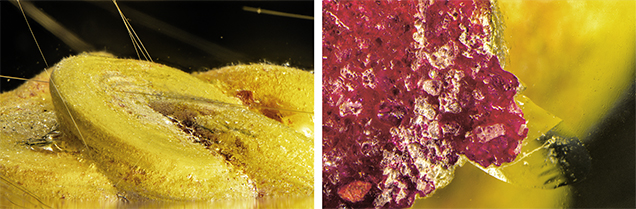

A 47 ct rutilated quartz cabochon exhibits an eye-catching yellow and red floral-shaped inclusion produced by creative carving and filling with a colored composite material (figure 1). Microscopic examination revealed circular marks from a rotary abrasive tool used to create the intricate cavity (figure 2, left). The cavity was subsequently filled with a yellow and red composite material of fine sand grains and a colored binder or resin (figure 2, right).

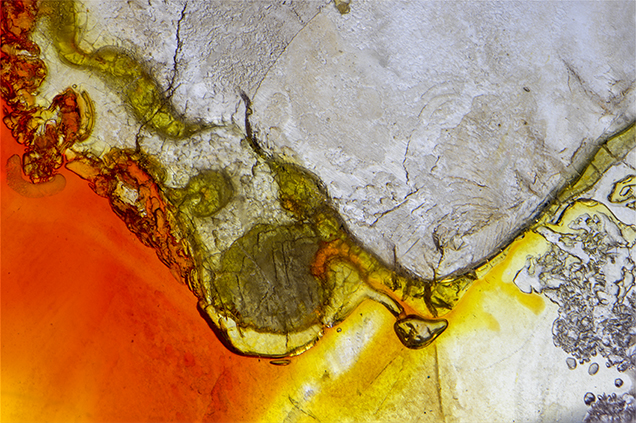

Another creatively manufactured inclusion in a quartz gem can be seen in a 226 ct round tablet containing a large fracture (figure 3). The fracture was filled with colored orange and yellow resin, which resembles natural iron oxide epigenetic staining sometimes seen in rock crystal quartz. A quick examination in the microscope revealed incomplete filling and trapped gas bubbles in the colored resin (figure 4), making the separation between this manufactured inclusion and its natural counterpart quite easy.

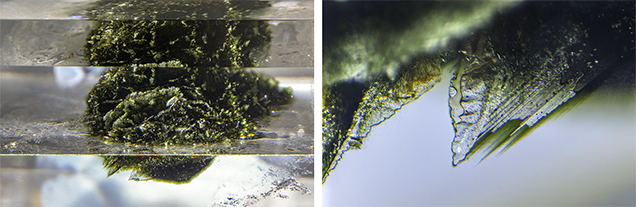

Creative dyeing also produced the manufactured inclusion in a 109 ct quartz with a completely enclosed green moss-like inclusion (figure 5). This stone consists of two pieces of rock crystal quartz, each with a centralized network of fine fractures that may have been artificially induced by laser, judging from their unnatural irregular pattern and striated appearance. The fracture network in each piece was subsequently filled with a dark green resin to give the appearance of a moss-like inclusion. The two halves were then glued together with colorless cement, completely enclosing the green moss-like inclusions in water clear rock crystal quartz. This left a somewhat obvious assembly plane (figure 6, left) when examined with the microscope, as well as trapped gas bubbles in the green resin-filled areas (figure 6, right).

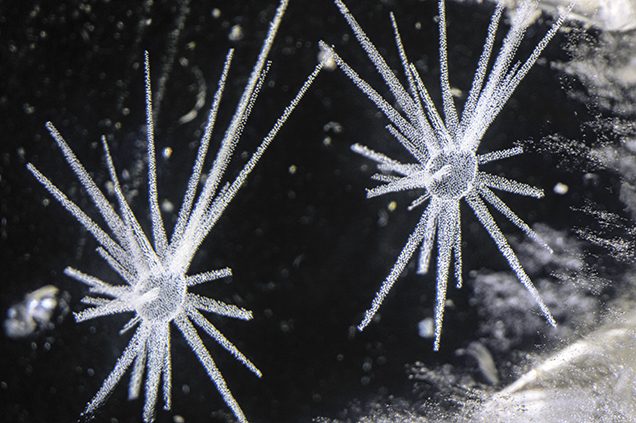

The fourth example of manufactured inclusions recently examined is a 724 ct quartz crystal with a polished face that contains two white stellate inclusions consisting of numerous radial arms surrounding a spherical core structure (figure 7). Closer examination revealed a carefully layered series of micro-fractures consistent with 3D subsurface laser engraving (figure 8). This is by far the most technologically advanced example of a manufactured inclusion in a gem material examined by author NR.

While these four examples of manufactured inclusions may not be quite as sought after as gems with natural inclusions, they certainly can be appreciated for the efforts and techniques employed by the manufacturers. Obviously, collectors of gems that feature inclusions should be aware that manufactured inclusions such as those described here exist in the trade. While some manufactured inclusions may be intended purely as an artistic enhancement, others may be produced with the intention to deceive the consumer, and caution should be used if a manufactured origin is suspected.