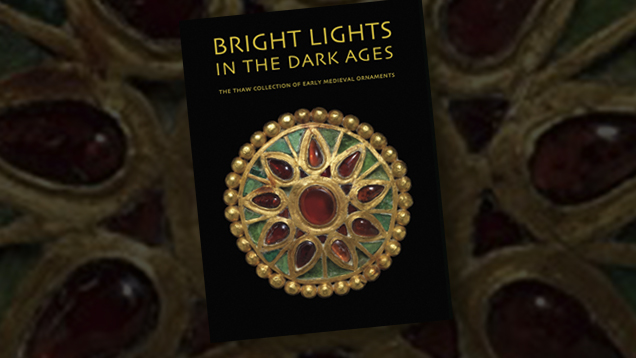

Books: Bright Lights in the Dark Ages: The Thaw Collection of Early Medieval Ornaments

Bright Lights in the Dark Ages is the seventh volume in which the Morgan Library and Museum documents a segment of the Eugene Thaw collection. Thaw’s many collections have been assembled over a lifetime, and he is considered the museum’s greatest benefactor since J.P. “Pierpont” Morgan himself. Art collector and dealer Eugene Thaw began acquiring ornaments from the early medieval period in the 1980s, leading to a systematic effort in 2001 to bridge the gap between the Museum’s ancient collections and its late medieval holdings. Thaw’s choices were based on aesthetic rather than scholarly merit, and he was advised on his acquisitions by the author of this book.

This volume focuses on small personal ornaments (brooches, buckles, and pendants), from Western Europe, including the United Kingdom and Scandinavia, to the Black Sea, that were fabricated in the early Middle Ages, often referred to as the “Dark Ages.” These small objects, often found interred with their owner in gravesites, are considered “portable wealth” and are usually interpreted by historians and archeologists as emblems of power and status.

The book’s narrow focus allows the author to address two objectives. The first is to challenge the preconceptions of art and culture of the “Dark Ages,” and the pejorative use of that term to describe a time that was actually quite culturally dynamic. The second is to demonstrate the continuity and evolution of metalworking from the 2nd century to the 10th century AD. To provide helpful context, the introductory sections outline the declining Roman Empire, the migration and invasion of new peoples and tribes from the East and the North, and the contraction of the Byzantine Empire.

The term “Dark Ages” refers to the death of classical literature in the sense that pagan tribes, specifically Germanic and Slavic “barbarians,” had rich oral traditions that eclipsed the written word following the disintegration of the Roman Empire. Other scholars of the 14th century regarded the dearth of written history, building activity, and artistic output as an indication of a “dark” time in history. Even today, “Hun,” “Goth,” “barbarian,” and, to a lesser degree, “Middle Ages” have negative connotations. Yet the barbarians and nomads, dismissed by the Greeks and Romans as having no culture or heritage, did recognize the sophistication of the Romans and sought to incorporate aspects of their culture, including classical forms and realistic imagery. In the 20th century, some scholars attempted to discontinue the pejorative use of “Dark Ages” and “barbarian,” promoting for a time the use of “migration period,” but the appellation and connotation appears to have been thoroughly embedded. The title of the volume seeks to challenge that preconception and to point out that all was not “dark” in this historical era.

The book features more than 100 examples of personal ornaments from this period from the Thaw collection, including fine metal, inlay, cloisonné, and mounted gemstones. The pieces were collected as singles and not as part of a grave burial collection. Through extrapolation from similar objects interpreted in a grave context, the pieces can be assigned to specific periods and regions. In interpreting the significance and meaning of the objects, Adams admits to having “committed one of the graver sins for the archeologist—the purposeful mixing of different types of evidence” in having used historical information to explain archeological findings and vice versa. The result, however, is a coherent narrative in which the reader can understand the significance and the sequence of the featured objects in an appropriate framework.

Following the introduction are six chapters examining different facets of the migration and invasions that bridged the transformation of Western Europe from a Greco-Roman world to the modern nation-states. The chapter introductions weave together history and cultural shifts (illustrated with maps), theories of visual art and personal adornment, and the state of craftsmanship/technology. Examples from other collections are included to better illustrate concepts. The remainder of the chapter is devoted to examples from the Thaw collection. Each is illustrated by a large-scale photo plus detail views. For those wanting technical details, the gemstones are identified and the jewelry making techniques are described. The stylistic attributes are discussed and the placement of the piece in its historical and cultural context is elaborated on, usually referencing other documented pieces. The photography and description are detailed enough to inspire and serve as a guide for a contemporary jeweler to design or manufacture archeological “revival” pieces that vastly differ from the Renaissance, Etruscan, or Egyptian objects associated with medieval influence.

The book ends rather abruptly, in the style of a catalog. The glossary could be more extensive, being dominated by geographic and historical periods rather than jewelry and stylistic terms. The bibliography attests ultimately to the scholarly nature of this work—it is an overwhelming 50 pages.

Trained as a geologist, art historian, and archeologist, Noël Adams brings her unique scholarly perspective to the technological aspects of metalwork. Less attention is paid to historiography, historical gender studies, cemetery analysis, dating analysis, and anthropological interpretations of burial ritual. The body of historical knowledge is augmented by examining how the pieces were physically made and the origin of materials, though one can only speculate how pieces were commissioned, supplied, bought and sold, or their meanings.

One favorite of Adams that was unfamiliar to me was “garnet cloisonné” or “framework cloisonné,” where garnets or glass pieces are collet set, giving the appearance of fired glass enamel. She defines this technique as “cold cloisonné” in the glossary. Examples are given of its evolution through Hunnic, Visigothic, and Merovingian periods of the 5th and 6th centuries.

I enjoyed this book because it gently made me aware of my own preconceived notions about the so-called “Dark Ages,” and then dispelled those notions. The early medieval period is one of the most complex in history—transitioning from long-established cultures of the Roman and Byzantine Empires to domination and displacement by very different peoples. The resulting turmoil eventually settled into an era of assimilation and comingling that would set the stage for a new era of creativity and progress, the “high” Middle Ages that eventually led to the Renaissance. In the introductory sections, the historical and cultural context is presented with just enough information to keep the interest of the average reader. Some of the chapters go into a level of historic detail that may be overwhelming to some, but gemological or jewelry enthusiasts can be satisfied by skipping to sections and illustrations focusing on medieval techniques and styles. Overall, Bright Lights in the Dark Ages is a worthwhile read.