Observations on Pearls Reportedly from the Pinnidae Family (Pen Pearls)

ABSTRACT

Pearls of all kinds have been used for decorative purposes throughout history. The majority of these have been nacreous, yet certain non-nacreous pearls have also been sought by connoisseurs. Pinna (pen) pearls fall into the latter group. The nature of their non-nacreous structure often results in cracking, and because of stability concerns they are very rarely used in jewelry. Nineteen of the 22 samples from this study, reportedly from Pinnidae family mollusks, show similarities in color as well as external and internal structure. Raman, photoluminescence, and UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopic results are discussed, along with the internal characteristics of pearls likely produced by this mollusk.

Mollusks of the Pinnidae family include the Atrina species and the more familiar Pinna species such as Pinna nobilis, as well as the rarely encountered Streptopinna species. Like many mollusks, this bivalve contains several members, including Atrina vexillum, Atrina fragilis, Atrina pectinata, Atrina maura, Pinna bicolor, Pinna muricata, Pinna rudis, and Pinna rugosa (Wentzell, 2003; Wentzell and Elen, 2005). The 22 pearls discussed herein (see figure 1) were submitted for examination by William Larson (Pala International, Fallbrook, California). They were all referred to as “pen pearls,” without any details concerning their recovery or provenance. Pen pearls have seldom been covered in the gemological literature, so the results presented here are intended as a reference for those interested in pearls from this important ocean dweller.THE MOLLUSK

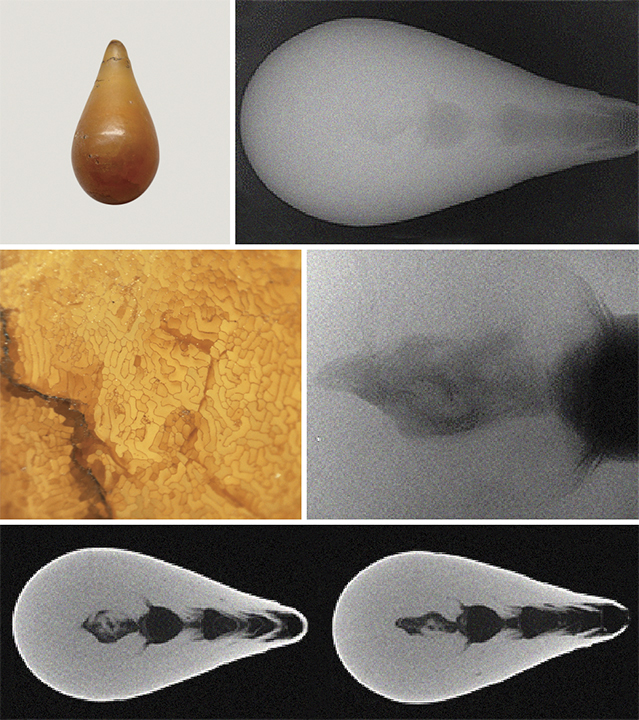

Bivalve shells from the Pinnidae family share a very characteristic outline, tapering from a broad curved end to a pointed tip (figure 2). This unique form, reminiscent of the quill pens once used as writing tools, gives the shell its name. Sometimes referred to as “fan clams,” they average 100 to 600 mm in length, though specimens approaching 800 mm (2.5 feet) have been recorded. Apart from size, another claim to fame for Pinna nobilis is that its byssal threads, which anchor the shell in the sand during the mollusk’s life, were once woven together to make a fabric known as “sea silk.”

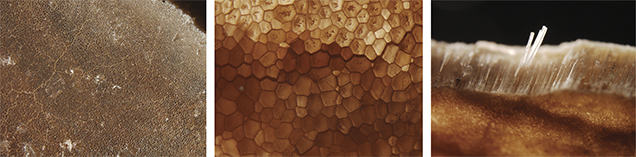

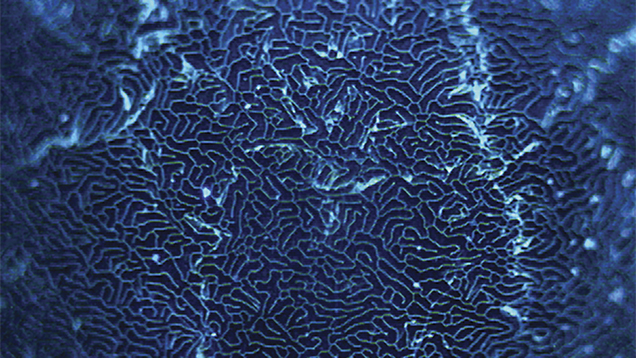

A quick glance at most Pinnidae shells shows a clear area of nacre at the pointed end and a less-lustrous portion extending across the curved opposite end. Closer examination reveals that the nacreous portions do not, as a whole, exhibit the obvious classic overlapping nacre structures encountered in other bivalves from the same order (Pterioida). Rather, they show a much finer form of nacre that is more difficult to resolve in most cases, even at high magnification (figure 3). This difference stems from the fact that the nacreous portion is not constructed of concentric layers, but of numerous small prisms arranged around the center (Taburiaux, 1985). Since the family comes from the same order as other nacreous species such as those of Pinctada and Pteria, it is not surprising that nacre should feature somewhere within the shells’ composition. But it is intriguing to see the different degree of coverage, given that the Pinctada and Pteria species are completely nacreous on their inner shells and clearly display overlapping platelet ridges.

THE PEARLS

Pen pearls occur in various shapes and sizes, and their color usually ranges from black or dark brown to a more yellowish brown or yellowish orange (Strack, 2006). This range of color was apparent in the samples we studied, where one of the drops stood out from the darker, more typical pearls. Most pearls form as cyst or whole pearls, but some—again in keeping with other mollusks—occur as blister pearls or blisters (figure 5; CIBJO, 2013). Blister pearls and blisters are particularly useful when trying to compare the structure of pearls to their hosts, as they occur together and provide a direct means of comparison. One of the greatest drawbacks of pen pearls, though, is their tendency to crack or craze, a characteristic that significantly hinders their market value. This cracking appears to occur only in the non-nacreous pearls, but unfortunately these specimens are the norm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

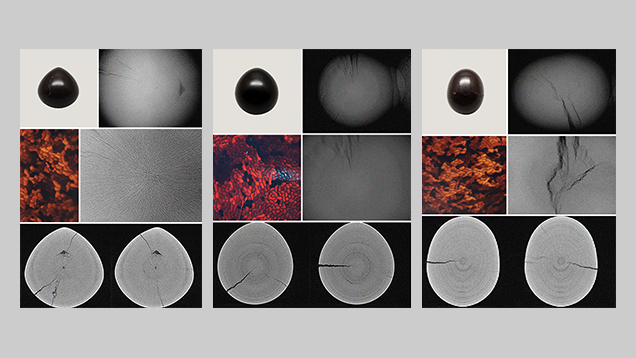

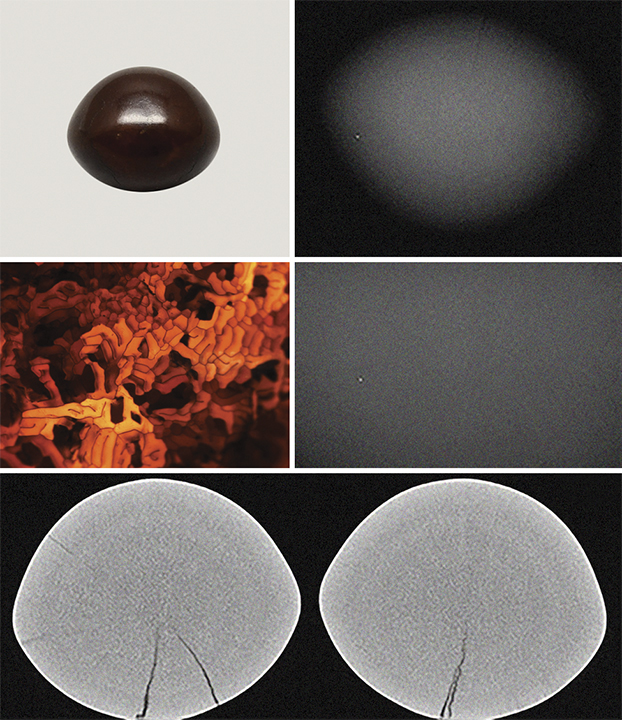

Twenty loose undrilled pearls, weighing between 2.74 and 20.70 ct and ranging in color from dark brown to yellow-brown, were analyzed. Two additional samples weighing 2.78 and 5.81 ct (see pearls 19 and 20 in table 1), exhibiting both silver nacreous and brown non-nacreous areas, were also examined. The properties of all 22 samples are listed in table 1.The pearls’ internal structures were examined using a Faxitron CS-100 2D real-time (RTX) microradiography unit (90 kV and 100 mA excitation), and a Procon CT-Mini model X-ray computed microtomography (μ-CT) unit fitted with a Thermo Fisher 8W/90 kV X-ray tube and a Hamamatsu flat-panel sensor detector.

Their composition was analyzed with an inVia Raman microscope equipped with a 514 nm argon-ion laser (Ar+), which was used to obtain Raman and photoluminescence spectra. The laser was set at 100% power, and spectra were collected using 10 accumulations, with an accumulation time of 10 seconds per scan.

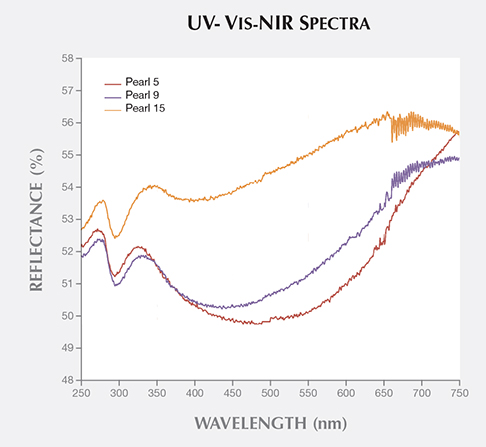

The spectra required to characterize each sample’s color were collected in the 200–2500 nm range with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 950 ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectrophotometer using a reflectance accessory fitted with an integrating sphere. The 250–750 nm range is presented here, because this range contains most color-related reflectance features.

The pearls’ chemical composition was analyzed using a Thermo X Series II laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) system equipped with an attached New Wave Research UP-213 laser and an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (EDXRF) unit. Microanalytical carbonate standards MACS-1 and MACS-3 from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) were used as the standards for each method.

Photomicrographs of the surface structures were captured with a Nikon SMZ1500 system using various magnifications up to 176×. Other gemological microscopes with magnification ranges between 10× and 60× were also used during the examination of the shells and pearls. Shells from both Pinna and Atrina species in GIA Bangkok’s reference collection were studied to compare their structural similarities with the sample pearls.

The pearls’ fluorescence features were also observed under an 8-watt UV lamp with both long-wave (365 nm) and short-wave (254 nm) radiation, as well as a DiamondView unit.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

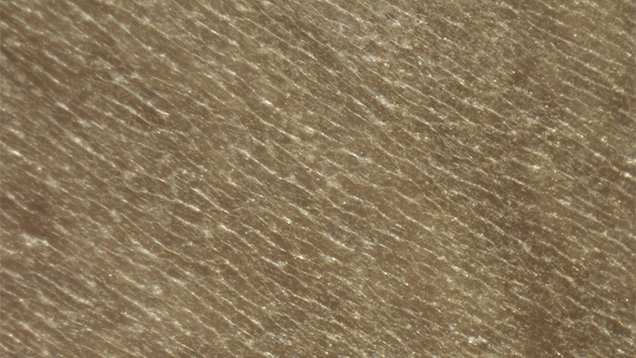

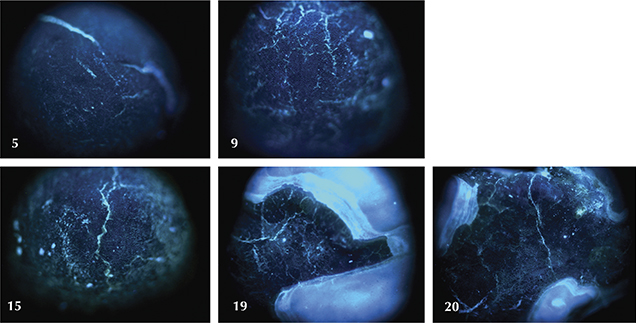

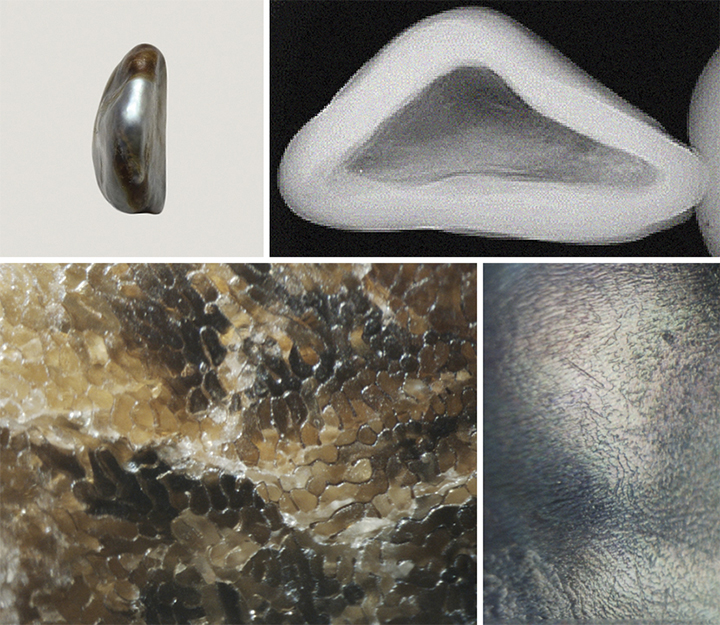

External Structure. The pearl samples showed characteristic non-nacreous structure consisting of a network of cells resembling those pictured in figure 4. The actual shape of the cells varied quite markedly, from a pseudo-hexagonal outline to an elongated curved form. Examples of the range of structures can be seen in figures 11–21. Diaphaneity ranged from opaque to semi-translucent, with the lighter-colored samples tending toward the latter (Gauthier et al., 1997; Karampelas et al., 2009). Cracking was very apparent in most of the samples, and some of the cracks were fairly wide and penetrated quite deeply. This is an accepted but undesirable trait encountered in most pen pearls. Using them as nuclei for atypical bead-cultured pearls solves this problem, since the nacre overgrowth hides not just the cracks but the whole pearl.Samples 19 and 20 were considerably different from the rest of the group. Their shapes were baroque and quite flattened, while their colors were clearly uneven and more bicolored, with silver and brown areas mixed together. Their structure also varied, from a more nacreous type with silver portions to a non-nacreous cellular structure on the brown portions (consistent with the other samples). These two pearls differed in other ways that will be described later in this work.

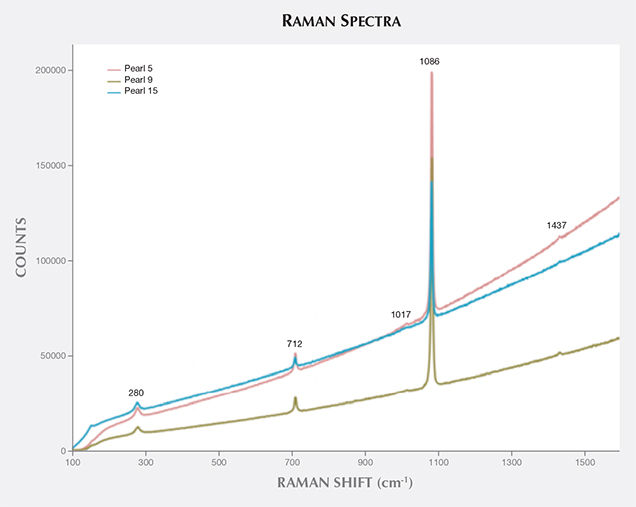

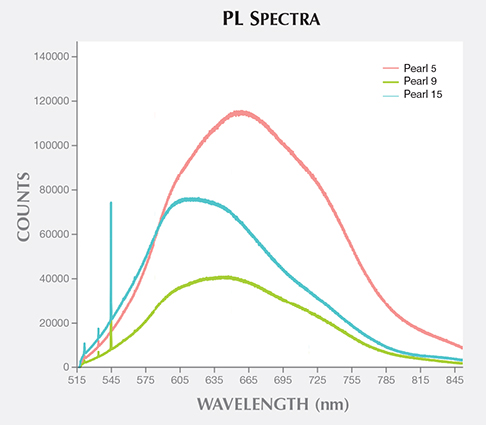

External Composition. To identify the nature of the minerals forming the pearls, we examined the pearls using the Raman spectrometer with an attached microscope. This analysis showed that the non-nacreous areas consisted of calcite, as evidenced by the peaks at 280 and 712 cm–1, with the associated band at 1086 cm–1 (figure 6). The only noticeable exceptions were the spectra for the two bicolored pearls, where the silver nacreous areas produced a slightly different spectrum. Here, the 280 cm–1 peak was very weak and accompanied by a series of peaks at 198, 206, 217, and 287 cm–1, while the 712 cm–1 peak position shifted to a doublet feature at 701 and 705 cm–1. These features are all characteristic of aragonite, the most common polymorph found in pearls and shells, so we were not surprised to detect it on the more nacreous portions. Previous studies on pearls from Pinna nobilis (Gauthier et al., 1997; Karampelas et al., 2009) attributed the cause of color to carotenoids. While we detected the 1017 cm–1 peak reported in their studies, the other peaks were not readily apparent, which is unusual. Such pigment peaks exhibit strong resonant phenomena. Their absence could be due to the particular mollusk that produced the pearls or the laser wavelengths used in collecting the spectra, as well as the parameters used to test the samples. No other lasers were used in this study.

patterns, likely due to the variation in their relative intensities. While the weak feature at

around 700 nm stayed consistent, the overall pattern of the peaks varied. The sharp

features at 520 and 550 nm are due to the Raman effect.

in color. The “noise” in the ultraviolet to visible region (250–750 nm) is likely due to the

pearls’ structure.

We turned to LA-ICP-MS, which examines a smaller micron-sized area of the surface and the underlying material and offers better sensitivity and element coverage. The results confirmed the pearls’ known saltwater origin on the basis of low manganese (Mn) levels and the expected results for boron (B), gallium (Ga), and barium (Ba). Strontium (Sr) levels were on average slightly lower than those usually recorded for saltwater mollusks, but still within the saltwater range. While they do not allow a direct comparison with pen pearl chemical composition, data collected from Pinctada maxima pearls show some similarities when each element is compared (Scarratt et al, 2012). Li and Fe were present in slightly higher concentrations in the pen pearls. The LA-ICP-MS results for the pen pearls are summarized in table 2.

Tables 1-2 (PDF)

The most significant differences observed between the nacreous and non-nacreous areas in samples 19 and 20 are highlighted by the bold numerals in the table. The most dramatic difference occurred with magnesium (Mg), which showed significantly lower concentrations in the nacreous areas than the non-nacreous areas of all the other pearls. The elemental concentrations in the non-nacreous areas of all 22 samples matched one another well, as would be expected for such similar-looking material. Many more samples of known pen pearls will need to be analyzed to determine whether any correlation exists, yet the detailed chemical analysis of pen pearls is not part of routine laboratory work.

Internal Structure. Viewed in cross-section, the internal structures of non-nacreous pen pearls appear to possess a distinct radial columnar structure. Not surprisingly, this radial structure often manifests itself clearly in microradiographic images, since the path length equals the entire thickness of the sample when exposed to the X-ray source. The clarity is usually not so obvious in the micron-thick slices of CT images. On the other hand, concentric ring structures are often more visible via CT than the RTX method. A selection of the thousands of RTX and CT slice images obtained by the authors appears in figures 11–21. These show that small, dark natural nuclei or cores sometimes exist at the center of the radial and concentric structures, while undesirable cracks also extend to various degrees throughout most of the samples.

Sample 15 exhibits the only atypical internal structure of the completely non-nacreous pearls in this study; it also differs in coloration and diaphaneity, as seen in figure 16. The structure consists of a series of connected voids and what are probably conchiolin-rich chambers that extend from the tapered point toward the broader end. The central irregular nucleus consists of another void/conchiolin-rich area that possesses an internal structure. Given the specimen’s size and the lack of commercial culturing of this mollusk, the pearl is almost certainly natural in origin.

It is worth noting that we observed a direct correlation between the structure (solid or hollow) and the specific gravity in these 22 samples. All the solid pearls (samples 1–18, 21, and 22) gave SG values between 2.39 and 2.53; this variation was likely due to the size and depth of the cracks and any air trapped in them during hydrostatic measurements. Samples 19 and 20 again proved the exceptions, with SG values of 1.76 and 2.02, respectively. Given the large voids observed in their structures, this was not surprising.

Culturing and Treatments. While many different mollusks are known to produce cultured pearls, most are bivalves associated with species from the Pteriidae family or various freshwater mollusks from the Hyriopsis genus that are frequently used to produce non-bead-cultured, mantle-grown cultured pearls (Farn, 1991; Strack, 2006). Cultivation using mollusks from other families is usually the exception rather than the rule today. The only other mollusks known to produce cultured pearls to any commercial extent are from the Haliotis genus and, on rare occasion, the Strombus gigas (Queen conch) species. Cultured pearls from the Pinnidae family can be added to the list of those that have undergone trials but without commercial success so far (Landis, 2010).

As with all pearls, the subject of treatments was often at the forefront of our thoughts on these pen pearls. No treatments were detected in this group, nor are the authors aware of any treatment applied to the Pinnidae family. Waxing or some other method could be used to hide cracks or prevent them from expanding and deepening, but no such procedure was observed in this study.

CONCLUSION

Pen pearls are among the least appreciated pearls due to durability issues and their rather plain appearance. Yet they possess one of the most wonderful internal structures of all mollusk creations, and the surface patterns revealed by magnification are truly remarkable works of nature that all pearl aficionados would do well to observe. The columnar structures in their radiating forms produce unique specimens that allow light to be transmitted along their length to varying degrees, causing some pen pearls to appear semi-translucent to the unaided eye. Not many pearls can lay claim to this characteristic.These radiating concentric structures manifest themselves clearly during examination with direct microradiography and X-ray computed micro-tomography (µ-CT). These techniques also demonstrate that in the 22 samples studied here, the structures do not always conform to the norm. Pen pearls 15, 19, and 20 showed void-related features that clearly differed from the other samples examined. The latter two also differed in their external nacreous and non-nacreous appearances, which leads one to question if they are indeed pen pearls. While we cannot be certain, the surface structure seen on the pen shell in figure 4 does bear a close similarity with the features seen in these two examples and in other pearls of reported pen shell origin occasionally examined in the GIA laboratory, so the nature of the nacreous structure appears to support this conclusion. Additionally, the non-nacreous calcitic areas typical of pen pearls are present in both pearls, further supporting the identity. It is noteworthy that both of these pearls, though outwardly different from the other 20 samples, share similar internal characteristics.

This work, along with those previously published by Gauthier et al. (1997) and Karampelas et al. (2009) appear to be the most comprehensive studies on pen pearls to date. Whereas the latter focused on pen pearls from a single known species of Pinnidae, the samples in this study are from unknown species and could come from several different members of the family.

The recent use of pen pearls as atypical nuclei to create natural-looking cores in cultured pearls has stimulated interest in these unusual specimens. The internal structures shown here will also serve as a reference for anyone studying the internal variations in pen pearls.

.jpg)