The Foldscope and Its Gemological Applications

Submissions were accepted for a beta test group (now closed) named the “10,000 Microscope Project.” The goal was to get a Foldscope in the hands of 10,000 users worldwide, in medical and non-medical fields. The project requested users who understood microscopy and agreed to write detailed scientific studies based on their own research, to be collected and published to show the variety of potential uses. Seeing a major application in field gemology, this author requested and received a Foldscope.

Beta testers received Foldscope components and instructions in December 2014. The body is made of a material more like plastic than paper, to prevent tearing. Pieces are punched out of perforated sheets and assembled like origami (figure 1). The kit also contained interchangeable low-magnification (140×) and high-magnification (400×) lenses, a 3V LED toggled light source, and a surprise: a coupler to connect to a cell phone for photomicrography. Due to its complexity, assembling the Foldscope may take an hour or two. The device was ingeniously constructed, but would it work with gems?

Stones between 1 and 3 mm could be mounted onto glass slides for study. Larger stones were held with gem tweezers in the slide opening, to test whether the Foldscope would work with loose stones as well. Stones that were transparent and relatively small produced impressive results. The use of a binder clip to hold the slide or tweezers in place freed the hands to manipulate the focus more precisely. Focusing was the biggest obstacle, and late in the research the author inadvertently scratched a lens while trying to focus on a 1 mm corundum culet.

Figure 2. This photomicrograph of synthetic opal, taken using the high-magnification lens (400×), shows the characteristic cellular mosaic appearance. Photomicrograph by Kate Pleatman.

It was possible to clearly distinguish between natural and synthetic stones, because the magnification levels were exceptional (figures 2–4). Yet the small fixed size of the slide opening made it difficult to use with loose stones in tweezers, and gems more than 8 mm in depth could not pass enough light to view. Opaque material was not visible at all.

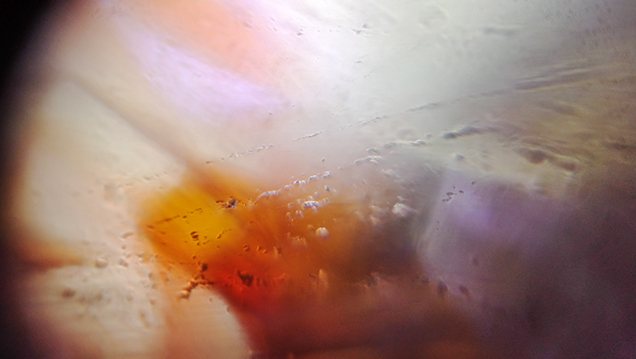

Figure 3. These fluid inclusions in quartz were taken using the Foldscope’s low-magnification lens (140×). Photomicrograph by Kate Pleatman.

Figure 4. These liquid inclusions in ruby are seen using the low-magnification lens (140×). Photomicrograph by Kate Pleatman.

Research details, photos, and feedback were sent to the Prakash Lab, along with design recommendations for making the device more ideal for gemological use. Suggestions included protection for the lens to prevent scratching and a larger gap for examining non-slide materials such as loose stones held with tweezers. An optional three- or four-inch fiber-optic light attachment would offer illumination from any angle, even for mounted stones. The Foldscope team has been very attentive to the feedback, although they have not committed to any alterations. Time will tell if the suggested modifications are feasible. No public release date or final price for the existing version has been announced. For more on this tool, visit www.foldscope.com.