Splendors from the Deep: Historic Treasures from a Spanish Shipwreck

Each summer, when the waters off Florida’s east coast are calm enough for shallow diving, treasure hunters from 1715 Fleet Queens Jewels explore the seafloor for artifacts lost in a Spanish shipwreck from 1715. The company is licensed to operate in an offshore area between the towns of Sebastian Inlet and Fort Pierce, where they mostly recover gold and silver coins and nuggets but have also unearthed jewelry adorned with precious gems (figure 1). GIA’s Carlsbad laboratory recently had the opportunity to study six pieces of jewelry recovered by the team, providing a glimpse into the treasures and skilled craftsmanship of colonial Spain.

HISTORY

Christopher Columbus’s four voyages to the New World between 1492 and 1502 sparked the Age of Discovery, a centuries-long period of exploration and colonization. The Spanish Empire, which funded Columbus’s journeys, initially sought a westward maritime trade route to Asia. Instead, the exploration led to an unprecedented expansion of trade routes between the Americas, Europe, and Asia, catalyzing globalization. The export of silver, mainly from Bolivia (Potosí) and Mexico, dominated transatlantic trade beginning in the late sixteenth century, with Spanish galleons transporting it—along with gold, gems, pearls, and other commodities—to Europe. While these Spanish treasure fleets supported the empire’s finances, they faced the considerable risk of tropical storms and hurricanes on the route to Spain.

One of the most historic and archaeologically significant Spanish fleets was destroyed by a fierce hurricane in the summer of 1715. Anchored at Havana, the 1715 Fleet was a formation of galleons from the Tierra Firme fleet and the New Spain fleet, as well as the French warship Griffon (https://1715fleetsociety.com/history). Eleven vessels set sail for Cádiz, Spain, carrying 14 million silver coins, as well as gold and other commodities (Newton, 1976). Three days later, the fleet was devastated by a hurricane; some of the ships sank, while others were driven toward the reefs along the eastern coast of Florida. The Griffon was the only ship to survive the disaster and arrive safely at a European port.

Modern salvage efforts begun in the late 1950s yielded a massive amount of Spanish New World silver and gold coins struck by the colonial mints of Potosí, Lima, and Mexico City, among others (Craig, 2000a,b). Loose stones, mainly emeralds, as well as silver and gold jewelry items have also been recovered.

The discovery of emeralds and emerald jewelry during these salvage efforts is not surprising. After conquering Bogotá in 1538, the Spaniards eventually gained control of Colombia’s rich emerald deposits. By the mid-1500s, Colombian emeralds, primarily from the famed Muzo mines, were being transported to European and Asian markets, adorning the European royalty and Indian Mughals. The nature of the jewelry recovered from the shipwreck suggests a thriving manufacturing industry in the New World employing expert artisans using locally sourced materials.

GEMSTONE TREASURES

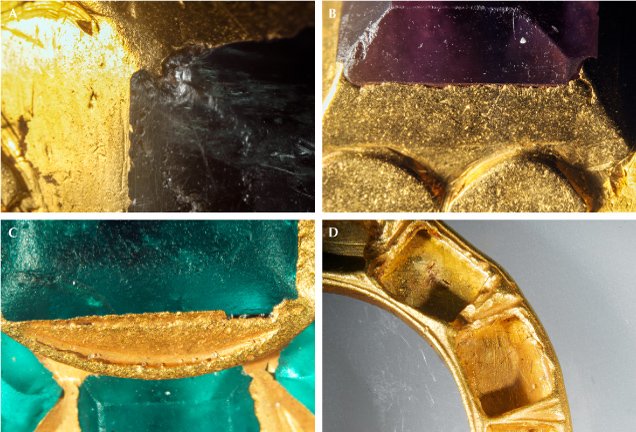

The most stunning example studied was a gold and emerald pendant containing 61 of the original 94 emeralds (figure 2). A second piece, a gold ring set with a Colombian emerald surrounded by two amethysts (figure 3), was also examined. All three stones in the ring were emerald cut with faceting styles common in Colombian emerald of this era, showcasing the color with a simple one-tiered step-cut pattern. The stones in both pieces were fixed in a bezel setting, with metal scraped or pushed over their edges to keep them in place. In some cases, this was evident from gold pushed into small cavities or fractures in the gem (figure 4A). The stones and the surrounding metal showed signs of wear from the slow action of water and sand, with pieces of gold flaked off near the girdle (figure 4, B and C).

The identity of the stones was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy and corroborated with ultraviolet/visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, and microscopic observations. The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of the emerald in the ring showed typical chromium and vanadium absorption features as well as the chromium fluorescence feature at ~685 nm, typical for emerald. XRF measurements of these emeralds’ chemistry supported a Colombian origin, given the very low concentrations of iron and potassium. While many of the emeralds had too poor of a polish to allow for inclusion observations, most showed jagged three-phase fluid inclusions, further confirming their Colombian origin (figure 5).

GOLD AND SILVER JEWELRY

Two gold chains, a gold ring, and silver cloak buttons recovered from the shipwreck were also studied (figures 6 and 7). The larger, thicker chain was assembled by mechanically bending and twisting thick gold wire into itself (figure 8, A and B). The manufacturing process for the small, finer chain was much more complicated, as one end of each link was clearly soldered in place (figure 8C). The careful soldering of the links, allowing for flexibility and movement, showcases the remarkable skill of these early jewelry artisans.

One interesting aspect of the jewelry was its metal composition. Except for the silver cloak buttons, most of the pieces were gold. Testing the metals with XRF gave precise measurements of their composition. The jewelers mainly used a high gold content with nonstandard karatage (typically from 20.1 to 21.5K, but with one 13.2K piece). Copper and silver made up the non-gold components of the alloys. The silver in the cloak buttons was also a nonstandard composition compared to modern jewelry, testing as 942 silver with copper making up the balance. The nonstandard gold and silver compositions likely result from the use of precious metals directly refined from natural sources, closely mirroring their Earth-derived composition.

A GLIMPSE INTO THE PAST

These pieces are just a small sampling of the remarkable treasures recovered from the Spanish galleons of the 1715 Fleet. Salvage efforts are ongoing every summer, and who knows where or when the next bounty will be revealed. Each artifact offers a fascinating glimpse into the craftsmanship, trade, and history of colonial Spain, shedding new light on a bygone era.