Zoned Trapiche Emerald with Goshenite Overgrowth

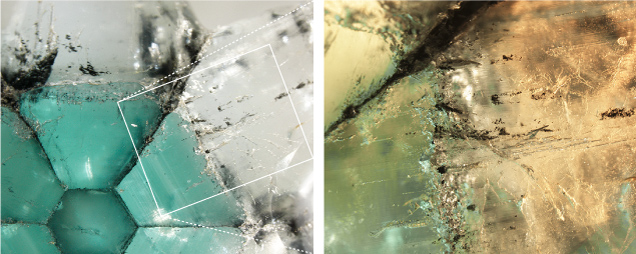

GIA’s Tokyo laboratory recently examined a 12.62 ct trapiche emerald with areas of the near-colorless beryl variety goshenite (figure 1). The stone was carved in the shape of a modified hexagram measuring 23.66 × 19.65 × 5.66 mm.

The internal features consisted of tubes, graphite, and jagged three-phase inclusions composed of a cube of halite (NaCl), a carbon dioxide (CO2) gas bubble, and water (H2O). Both the green and the near-colorless areas showed similar Raman spectra consistent with a beryl structure and spot refractive index readings of 1.57, matching that of beryl. The nearly identical Raman spectra patterns and intensity ratios indicated that the crystal axes of both areas were aligned. Some of the inclusions such as tubes were also in agreement with the internal fibrous growth structure of both the green and the near-colorless arm areas. These points suggested that both green and near-colorless arms were almost in the same crystallographic direction (figure 2).

The green core and green arms showed hexagonal weak green color bands. Absorption lines and bands related to trivalent vanadium (V3+) and chromium (Cr3+) were detected by a handheld spectroscope and an ultraviolet/visible absorption spectrometer in the green area but not in the near-colorless area. Chemical analyses using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) demonstrated that the green trapiche area was consistent with a Colombian origin and the near-colorless goshenite area was poorer in minor elements of sodium, magnesium, vanadium, chromium, and iron while richer in potassium and cesium than the green core and arms (table 1). (The behavior of rubidium is unknown with this chemical measurement method.)

Next, we considered the processes that might have formed such a zoned trapiche emerald. The finest trapiche emeralds are found in the Colombian deposits on the western side of the Eastern Cordillera Basin (e.g., Muzo, Coscuez, and Peñas Blancas), characterized by folding and thrusting along tear faults at the time of the Eocene-Oligocene boundary between 38 and 32 million years ago. Accumulation of hot H2O-NaCl-CO2 fluids at the tip of décollement faults in black shale host rock led to maximum fluid overpressure and subsequent sudden decompression associated with the collapsing of rock, forming emerald-bearing vein systems. The rapid growth of trapiche arms was shown to start at the beginning of decompression (e.g., I. Pignatelli et al., “Colombian trapiche emeralds: Recent advances in understanding their formation,” Fall 2015 G&G, pp. 222–259).

Pignatelli et al. (2015) performed EDX elemental mapping using an electron probe microanalyzer for sodium, magnesium, aluminum, vanadium, and chromium on a trapiche beryl, which consisted of a near-colorless core and arms and green overgrowth areas. The green overgrowth areas were richer in sodium, magnesium, vanadium, and chromium than the near-colorless core and arms. The behavior of these trace elements corresponds to the color and is consistent with our EDXRF results on the present stone, which showed an inverse color distribution. In addition to these trace elements, we examined potassium and cesium and found for the first time that they behaved in a manner opposite to that of sodium, magnesium, vanadium, chromium, and iron.

Such chemical differences could be due to either compositional changes in the incoming fluids themselves in a simple open system or fluid differentiation associated with emerald crystallization in a closed system. Various chemical elements will behave differently to changes in pressure or temperature of the mineralizing aqueous fluid in such a system. For instance, elements such as potassium and cesium, with a so-called positive partial molar volume, will be released from the fluid due to increased pressure and/or decreased temperature (e.g. table 1; T.W. Swaddle and M.K.S. Mak, “The partial molar volumes of aqueous metal cations: Their prediction and relation to volumes of activation for water exchange,” Canadian Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 61, No. 3, 1983, pp. 473–480; E.L. Shock et al., “Inorganic species in geologic fluids: Correlations among standard molal thermodynamic properties of aqueous ions and hydroxide complexes,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 61, No. 5, 1997, pp. 907–950). These elements are concentrated in the colorless goshenite areas. On the other hand, V3+ and Cr3+, with a so-called negative partial molar volume, would have reacted in the opposite way and are depleted in the goshenite but enriched in the emerald areas, indicating a change in the pressure and/or temperature of the fluid as it crystallized either goshenite or emerald. The classical chemical thermodynamic considerations above may provide insight into the differences in behavior among trace elements and the growth history that zoned gems such as this stone have undergone in fluids or melts.

This trapiche emerald offers a unique example to consider trace element behavior and geological conditions during crystal growth, as well as the diversity of trapiche emerald formation.

.jpg)