Update on Mozambique Ruby Mining and Trading

Less than 10 years after discoveries inside the Niassa Reserve in 2008 and near Montepuez in 2009, rubies from northern Mozambique have taken a significant place in the trade. During the first few years, production came exclusively from unlicensed miners known as garimpeiros, who sold their production mainly to Thai, Sri Lankan, Tanzanian, and West African traders. The stones were smuggled to cutting and trading centers such as Thailand. The situation changed when Gemfields, which acquired mining licenses near Montepuez in 2011 and began operations in 2012, held its first rough ruby auction in Singapore in June 2014.

Since 2015, three factors have affected that dynamic, starting with an efficient low-temperature heat treatment technique developed in Sri Lanka and brought to Mozambique. As the treatment is very difficult to detect without lab instrumentation on faceted stones and even more so on rough, the challenge for dealers buying stones from garimpeiros was to avoid paying unheated ruby prices for stones that had been already heated. Many buyers purchased heated rough in Montepuez only to find out later in Thailand about their costly mistake. Within a few months, confidence in the stones from that network deteriorated and dealers found out that the only safe options for unheated rubies were to buy directly from Gemfields or to get reliable laboratory testing on any stones obtained elsewhere. The situation became difficult for those willing to take their chances buying illegally in Mozambique.

In early 2016, another significant change took place when the Mozambican government changed its policy on garimpeiros. Before 2016 the garimpeiros were, legally speaking, “informal” small-scale miners. The only legal issue was that they had no license. The police were only allowed to confiscate their mining equipment and question them before releasing them. But in 2016, mining for gemstones or gold without a license became a crime punishable by three years in jail. In February 2017 the government, which was facing major fiscal problems, changed tactics: Instead of taking legal action against garimpeiros, they would target buyers hiding in the towns. Several police operations were launched in Cabo Delgado, and many foreign buyers (mainly Tanzanian, Thai, Sri Lankan, and West African) were arrested, fined, and expelled. Rubies quickly became more scarce in the Thai markets. This probably explains why Gemfields had its most successful ruby auction ever in June 2017, recording more than US$54 million in sales.

Finally, as previously reported (W. Vertriest and V. Pardieu, “Update on mining in northern Mozambique,” Winter 2016 G&G, pp. 404–409), two new mining companies, Mustang Resources and then Mozambican Ruby (formerly known as Metals of Africa), began operations near Napula village, north of the road linking Montepuez to Pemba in areas neighboring Gemfields. As these companies have not yet sold any production, their impact is still unknown.

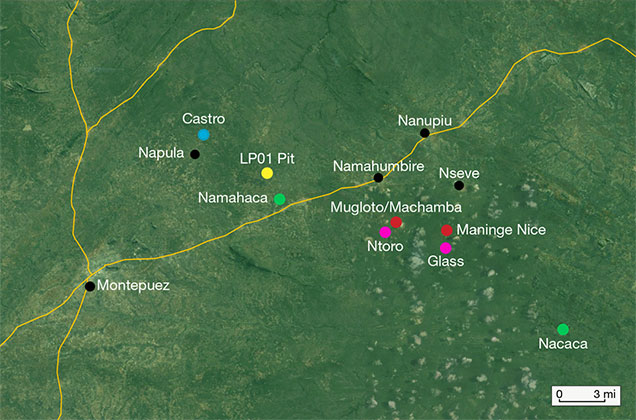

In June 2017, the author visited northern Mozambique (figure 1) for the sixth consecutive year to collect reference samples. This time it was for Danat, the newly formed Bahrain Institute for Pearls & Gemstones. The team was composed of jewelry designer Erica Courtney; Dr. Cedric Simonet, a geologist with extensive experience in East African gem deposits; and a photographer and videographer.

Unlike previous years, we visited the area at an early stage of the dry season, which extends from June to November. The land was still green, and upon arriving we were struck by the lack of activity at the main garimpeiro villages on the road between Pemba and Montepuez. While in previous years we could see thousands of people and hundreds of shops at Nanupiu and Namahumbire, this time there were maybe a few hundred people in the streets and most of the shops were closed. It seemed that most of the garimpeiros had moved to other parts of the country.

MRM (Montepuez Ruby Mining): Our visit to the MRM mine, owned by Gemfields and its local partner Mwiriti Limitada, took place during the record-breaking ruby auction in Singapore and a few days after Pallinghurst, Gemfields’ main shareholder, attempted a takeover. We also saw representatives from the Chinese conglomerate Fosun, which was also looking to acquire Gemfields. The mine staff was thrilled by the results of the Singapore auction but uncertain about Gemfields’ future. Afterward we learned that Pallinghurst was successful in the takeover. Gemfields was delisted from the London Stock Exchange on July 28, and a few days later Gemfields CEO Ian Harebottle announced his resignation. He was replaced by Sean Gilbertson.

Besides the excitement about the auction and the legitimate questions about the future of Gemfields, we observed some interesting changes at MRM. First, MRM continued to improve its mining and sorting capacity. Figure 2 shows a dense media separation (DMS) plant that became operational in December 2016, replacing the previous system of pulsating jigs. The results were said to be very encouraging, particularly regarding small material. Before, all material under 3 mm was rejected and stockpiled. With the new DMS plant, rubies under 3 mm can be collected very efficiently, and MRM’s washing capacity has increased from 80 to about 150 tons per hour in ideal conditions. The sorting house scheduled to go next to the new DMS plant in 2017 will not be completed before summer 2018. Visiting the existing sorting house, we saw few improvements in rough processing efficiency. The author was able to once again select samples from recent production. These were mainly high-clarity, attractive rubies from the classic Mugloto/Machamba area, which has produced most of the stones auctioned by Gemfields since 2014.

Exploration continues, meanwhile, and mining is being planned for new areas east and west of the current pits at Mugloto/Machamba (producing secondary-type, iron-rich material with high clarity) or Maninge Nice (producing primary-type stones with moderate iron content and more inclusions and fractures). Glass, a secondary deposit south of Maninge Nice, was not bringing as much as expected, as it had been extensively worked by garimpeiros since 2009.

In summer 2017, the MRM mine employed 450 people. Including security and contractors, that number is more than 1,100 employees. Concrete houses have replaced the cargo containers once used as living quarters, and life there is now much more comfortable. Since the construction of the main camp, MRM has been able to focus on corporate social responsibility, and we could see significant results that have improved MRM’s image in local communities. The company has built schools at Namahumbire and Nseve. We saw two chicken farms that appeared to be sustainable, and six farming associations created and supported by Gemfields. At Nseve, we visited a farming pilot program that could become very successful, as the area was fertile during Portuguese colonial times when the nearby reservoir was built. Agriculture disappeared after the civil war, which destroyed the local communities and the economy. MRM is also financing a mobile health clinic, enabling government doctors to visit different villages each day to serve those with little access to health care. Finally, we could see that Gemfields was continuing to support conservation and community development in the Niassa Reserve with the “Niassa Lion” project.

Mustang Resources: In 2016, the author reported on the emergence of Mustang Resources, which acquired mining licenses in 2015. At the time they were focused on exploration and camp infrastructure. Mustang has been quite active, and the operation now employs about 130 people. A modern washing plant using rotary plants (figure 3) is in place. Jigs (the small “Bushman jig” version used for prospecting) and a small sorting house have been built. Mustang decided to concentrate on LP01, a promising area in the south of the concession where gem-rich gravels could be found at less than one meter depth. Operating at such shallow depth is inexpensive, as there is little overburden to be removed. The area had been discovered by garimpeiros (figure 4), and we saw mining from both Mustang and local villagers.

The stones are similar to those found in Glass or around Nacaca village (an area open for garimpeiros to the east of the Gemfields concession). This means that these are mainly secondary-type rubies that spent millions of years in gravels and show some abrasion. They have a fine pink to deep red color and are quite clean with rare fractures, but they tend to be smaller and their color is brighter than the production at Mugloto/Machamba, which has a higher iron content. We saw several fine clean rough stones up to 10 carats, but most of the production was under 1 carat.

We were informed that Mustang planned to have its first rough ruby auction at the end of November 2017 in Mauritius, as several tens of kilos had already been mined.

Mozambican Ruby Lda.: While significant changes were visible in areas worked by Mustang and MRM, the same could not be said for Mozambican Ruby Lda. The project was clearly still in an early stage, with only a few employees and very basic equipment. The exploration program has nevertheless advanced considerably since last year, and more equipment is expected to arrive this year. The project is led by a small private company with a rather cautious approach. We visited the different pits mined by garimpeiros during the author’s previous visit in 2016. The two pits at Castro were flooded and mainly being used by garimpeiros as a water reserve for washing the gravel they collected around the pit. The area seems to have great potential.

Our visit to the Montepuez area showed the evolution of ruby mining by MRM, Mustang, and Mozambican Ruby Lda., as well as by the garimpeiros. It now seems that the legally operating mining companies are gaining the upper hand over the garimpeiros and the foreign buyers who smuggle stones to trading centers in Tanzania, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. It will be interesting to see what happens with Gemfields under Pallinghurst’s full control and the impact of forthcoming production from Mustang.

.jpg)