Orange Faceted Eosphorite

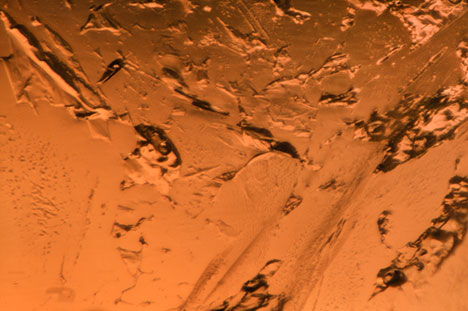

The Carlsbad laboratory recently examined a 5.85 ct transparent orange oval mixed cut for identification services (figure 1). Standard gemological testing showed an RI of 1.640 to 1.667; the hydrostatic SG was 3.12. The stone showed yellow and reddish orange pleochroism. Fluorescence was inert to long-wave and short-wave UV radiation. The most distinctive internal characteristic, revealed by microscopic examination, was the presence of multiphase inclusions (figure 2), suggesting a formation process with the presence of water, such as pegmatitic and hydrothermal processes.

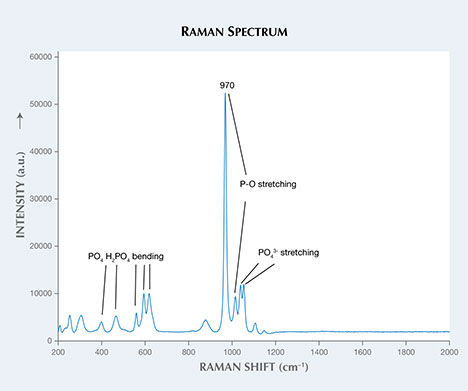

Raman spectroscopy confirmed that the stone belongs to the childrenite-eosphorite mineral series (figure 3), with intense peaks observed at 970 and 1011 cm–1. These peaks are attributed to the P-O (phosphorus-oxygen) stretching vibrations (R. L. Frost et al., “Vibrational spectroscopic characterization of the phosphate mineral series eosphorite-childrenite-(Mn,Fe)Al(PO4)(OH)2·(H2O),” Vibrational Spectroscopy, 2013, Vol. 67, pp. 14–21). This mineral series has a stoichiometric formula (Mn,Fe)Al(PO4)(OH)2·(H2O). Visible absorption spectroscopy revealed that the stone’s orange color results from the combination of Fe and Mn (M.A. Hoyos et al., “New structural and spectroscopic data for eosphorite,” Mineralogical Magazine, 1993, Vol. 57, pp. 329–336).

Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) analysis revealed a composition of 25.10 wt.% Al2O3, 31.74 wt.% P2O5, 15.46 wt.% MnO, 11.47 wt.% FeOtot, 0.49 wt.% MgO, 0.25 wt.% CaO, and 15.50 wt.% H2O (water weight percent is assumed from references). The stone contains 55.3 mol.% eosphorite and 40.5 mol.% childrenite. The calculated formula is

(Mn0.48Fe0.35Ca0.01Mg0.03)(Al)1.09(P0.99 O4)(OH)2·0.91(H2O), which indicates an intermediate member of the childrenite-eosphorite series with predominance of the Mn phase. As a result, the stone should be classified as eosphorite.

Eosphorite is the manganese-rich end member of the childrenite-eosphorite series, formed worldwide in pegmatites (T. J. Campbell and W. L. Roberts, “Phosphate minerals from the Tip Top mine, Black Hills, South Dakota,” Mineralogical Record, 1986, Vol. 17, pp. 237–254) or by hydrothermal phosphatization of metasediments and associated with the intrusion of granites (R. S. W. Braithwaite and B. V. Cooper, “Childrenite in South-West England,” Mineralogical Magazine, 1982, Vol. 46, pp. 119–126). This was the first faceted eosphorite examined by GIA’s Carlsbad laboratory.