Freshwater Pearling in Tennessee

October 7, 2016

North America has a long history of natural pearling owing in part to its very diverse and rich freshwater mussel resources. After the Civil War pearl jewelry gained greater popularity in the United States than in Europe. To some extent this popularity was due to European fashion icons but more significantly was influenced and supported by the exciting discovery of freshwater pearls in U.S. rivers and lakes, especially in the southeastern states. Pearl was officially designated Tennessee’s state gem in 1979, but for people living along the rivers, it has always been a part of their lives.

harvested pink heelsplitter from the Tennessee River. This was the first mussel shell

–hunting trip for Sabrina and for the GIA research team. Photo by Tao Hsu/GIA.

In 1984 James Sweaney and John Latendresse introduced Gems & Gemology readers to the American freshwater pearl industry. Around the same time, the Latendresse family harvested the first crop of American freshwater cultured pearls from their Birdsong Creek pearl farm in Camden, Tennessee. Thirty years have passed since this introduction with no update. In June 2016 GIA sent a collaborative team to revisit the Latendresse family and the pearl farm. While the researchers focused on sampling the freshwater pearl mussels for DNA bar coding, the education crew collected information for a complete industry update.

with the American Pearl Company

During this short field trip, the team went on an expedition on the famous Kentucky Lake, where our diver and guide Don Hubbs dove to collect five different pearl mussel species samples. Don is the mussel program coordinator at the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) and has worked for the agency for over 25 years. The samples are important for GIA’s pearl research DNA bar coding project. We also visited the once-booming town of Camden and the Birdsong Creek pearl farm. The last day of the trip was spent at the American Pearl Company’s Nashville office for an informative discussion with Gina Latendresse (John Latendresse’s daughter), the company’s current president. We are very grateful to have had the opportunity to see the Latendresses’ remarkable pearl collection.

THE TENNESSEE RIVER AND KENTUCKY LAKE

The Tennessee River’s main stem begins near Knoxville, in eastern Tennessee. Roughly 652 miles (1049 km) long, the river is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. From Knoxville the river flows southwest, crossing into northern Alabama, where it travels west through the state and forms part of the border with Mississippi before looping back to Tennessee. In Tennessee the river divides central and western Tennessee. The group drove west from Nashville to cross this section of the river. The pearling town of Camden is just west of the river.

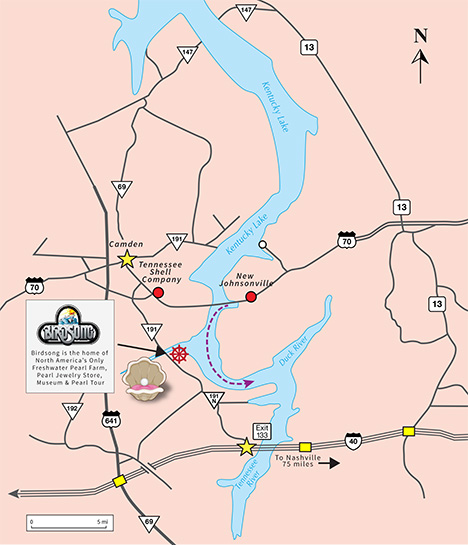

Kentucky Lake sits across northwestern Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. It is the largest reservoir in the eastern United States, created after construction of the Kentucky Dam in 1944. The lake is about 184 miles (296 km) long and marks the end of the Tennessee River before it connects to the Ohio River. Today the multifunction dam, reservoir, and nearby land are major tourist magnets. People travel to this region from all over the country to enjoy the appealing views, the water activities, and the rich history of the river. The Birdsong Creek pearl farm is close to the western shore of Kentucky Lake, near Camden. The mussels collected for the DNA bar coding project were obtained from this section of the lake.

route of the group’s boat trip is indicated by the purple dashed line on the map. Since

this was once rich farmland, an ample plankton supply enabled freshwater mussels

to thrive. The pearl farm once owned by John Latendresse is located at the Birdsong

Creek Marina, now a popular tourist attraction. Historically most of the mussel shell

divers and buyers settled in Camden.

TENNESSEE'S HISTORICAL PEARLING

Tennessee’s freshwater pearl and mussel shell industry began with the outbreak of a “pearl rush” on the Clinch River in eastern Tennessee just before the turn of the century. The period from 1895 to 1936 was the beginning of Tennessee’s prominence as one of the nation’s leading states in pearl marketing and production. Tennessee’s pearl history is therefore a microcosm of that of the eastern United States.

The first third of the 20th century witnessed the boom of a multimillion-dollar mother-of-pearl button industry in Tennessee. While the button industry came to an end in the 1950s due to labor and cost issues, the commercial shell industry did not die with it. To satisfy the high demand of the Japanese cultured pearl trade, thousands of tons of American freshwater mussel shells were exported each year after World War II. The profitable business lasted from the 1940s to the 2000s. During its heyday, from roughly the 1960s to the 1990s, Tennessee’s commercial mussel shell business employed about 2,000 people and provided nearly $50 million in state revenue. Close to 90% of the cultured pearls produced worldwide during this time had nuclei (kaku in Japanese) made of American freshwater shell.

Mussel fishing was once accomplished with brail boats. Brails are long upright poles or supports with hanging clusters of brail hooks. The brails are lowered into the water so the hooks touch the mussels. The mussels close on the hooks in a reflex reaction and can be harvested.

By 2000 pearl culturing in Japan had shrunk dramatically to only about 20% of the scale of the 1990s, due to severe pollution and the Asian economic crisis at the end of the decade. China quickly became the main freshwater cultured pearl supplier. Unfortunately China has never been a large consumer of U.S. freshwater shells. The vast majority of Chinese production is tissue nucleated instead of bead nucleated.

A brief history of freshwater pearl culturing in Tennessee partially overlaps with the history of the mussel shell business. Before pearl culturing all American pearls were natural and collected by divers. John Latendresse, founder of the American Pearl Company, was the pioneer who brought pearl culturing to the United States and first successfully harvested pearl crops here. Latendresse was initially involved in the mussel shell and pearl trading business in Japan. When he was challenged by his Japanese friends, he became determined to culture freshwater pearls in the United States. From 1963 to 1983 he experimented on pearl culturing with the help and support of his Japanese wife, Chessy. After 20 years’ hard work, the family finally harvested their first bead-nucleated American freshwater pearl in 1983. For many years their farm at Birdsong Creek produced cultured pearls for jewelry retailers, and it now supplies only the on-site gift shop.

pearl farm. The Latendresses cultured many different shapes of pearls and blister pearls.

Photo by Artitaya Homkrajae/GIA.

After John Latendresse passed away in 2000, the farm was transformed by its current owner, Robert Keast, into a 58-acre recreational complex. Hosting a small-scale pearl culturing farm and the Tennessee River Freshwater Pearl Museum, the Birdsong Creek Marina and Resort is now open to the public and has become a popular attraction. The Latendresse family has stopped pearl culturing but still runs their pearl business in Nashville. The company is overseen and operated by Gina Latendresse, John and Chessy’s elder daughter. To learn more about the Latendresse family, their remarkable pearl collection, and their business, please read the coming article “Catching the Orient of American Pearls.”

A RICH FRESHWATER PEARL MUSSEL RESOURCE

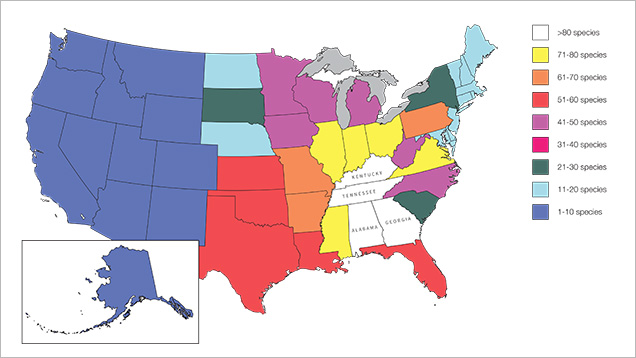

Compared to the rest of the world, North America has an extremely diverse molluscan fauna. Among the 1,000 known species, approximately 300 are found in North America, with the highest concentration in the southeastern United States. The aboriginal Indians benefited from this resource for food, tools, and simple decorations. Surprisingly they were never enthusiastic about the pearls they recovered from the mussels. Since the odds of finding a natural pearl are outrageously low (less than 1 in 10,000), a tremendous number of mussels is necessary to support a natural pearl industry. This is true even for the cultured pearl industry because of the high mortality and rejection rate.

Unlike the ocean’s pearl oysters, freshwater mussels need a very strict living environment to survive and reproduce. The mussel babies, called glochidia, are parasites of fish. Without the host fish, they cannot survive. The juveniles live in the sediments for years before they are mature enough to produce offspring. Although pearl mussels are among the most long-living animals on the planet, with some centuries old, the United States faces the critical situation of a dramatic reduction of the pearl mussel population. The concern has lingered since the end of World War I, when people began building dams along the major rivers and many Tennessee River tributaries. Many mussel species and their host fish species lost their stable habitats. The overharvesting occurred during the prime of the mother-of-pearl button industry, and the mussel shell industry also severely reduced the population of many important species. In addition, pollution, exotic species introduction, and even global warming all threaten mussel populations.

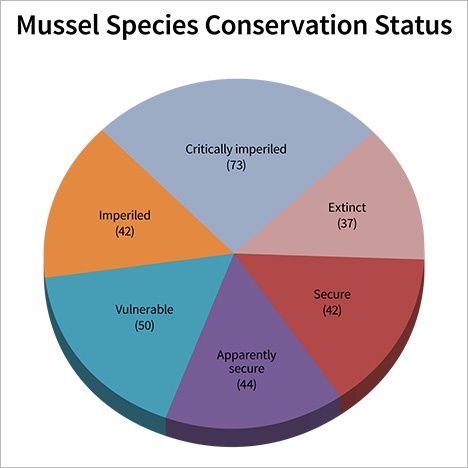

due to overharvesting, habitat destruction, and exotic species invasion. Chart reproduced

from Strayer et al., “Changing Perspectives on Pearly Mussels, North America’s Most

Imperiled Animals,” BioScience, Vol. 54, no. 5, 2004.

Altogether these negative factors have put 70 mussel species on the endangered list and many more candidates in the queue. Since some species live for a long time even under a negative growth rate, the number of species might not currently seem to be shrinking much. However, the negative growth rate means we are accumulating a huge “extinction debt” until the payday comes.

The shells that fit smoothly through the rings are below legal harvesting size and will

be returned to the river. Photo by Tao Hsu/GIA.

Our river guide and diver Don Hubbs introduced us to the mussel species and their conservation on Kentucky Lake. To protect the resource from exhaustion, harvested mussels smaller than their legal size limit should be released back to the water. Different species have different size limits. Divers gauge size by measuring the harvested mussels against metal rings of different sizes. If they are too big to go through the ring, they are legal to harvest. Otherwise they should be released following the regulations. Divers who do not follow this rule are fined. Divers harvesting shells for commercial purposes also need to purchase a license. Hubbs and his colleagues patrol the lake to monitor the mussel populations, research the endangered species, and check for illegal harvesting.

Through the efforts of river conservationists and thanks to the smaller mussel shell industry, the population of major pearl mussels in the area has gradually increased. According to Hubbs, in the past 10 to 15 years, commercial mussel shell harvesting was less than 100 tons annually, dramatically reduced from thousands of tons per year 20 years ago. In 1999 TWRA updated its legal size limit for washboard, the most valuable shell species, from 3.75 to 4 inches. This will help further protect this mussel.

Hubbs is very positive about the future of Kentucky Lake’s freshwater mussel population and confident about the sustainability of the lake with a certain amount of mussel harvesting. He also informed us that many students are involved in freshwater mussel conservation programs at major universities such as Virginia Tech and Tennessee Tech. When asked about the amount of mussels people can harvest, he said that 500 to 600 tons a year would be tolerable.

Freshwater Mussel Resource

years. Don is proud of the TWRA’s work on mussel preservation on Kentucky Lake.

Photo by Artitaya Homkrajae/GIA.

DIVING FOR PEARL MUSSELS, AND THEIR DNA BAR CODING

A primary goal of the trip was to collect important pearl mussel shells from Kentucky Lake for DNA analysis in order to help with pearl identification. Don Hubbs collected the shells by diving to the bottom of the lake and handpicking the mussels.

“Toe digging” is one way to locate possible mussel beds since they are partially exposed above the muddy sediments. This activity can easily be carried out by people who can’t dive. However, toe digging can only be performed in shallow waters, which are not necessarily the ideal conditions in which to search for mussels. The distribution of freshwater mussels is very patchy, in areas ranging from centimeters to kilometers wide. Locally mussels tend to cluster into sedimentary beds. To find the targeted beds for certain species, an experienced local diver is helpful. As a local, Don is very familiar with the environment, especially the mussel beds.

The GIA crew boarded one boat with Gina Latendresse and her daughter, while Don took the TWRA boat to lead the way. Both boats set off from New Johnsonville. It took about 10 minutes to arrive at the first sampling spot. Diving is not an easy task. The poor visibility makes it unpredictable and to a degree scary. Some locals told us that diving in the river was the scariest experience they had endured in their lives. In addition to the conditions at the bottom of the lake, the threats of people, boats, and barges on the surface of the water can be devastating. Certain rules need to be strictly followed to create a safe diving experience.

At the diving spot Don hoisted two flags to warn people of the divers below. They are called Diver Down Flags; Internationally, the code flag Alpha is blue and white, and in North America it is red with a white stripe from upper left corner to lower right corner. Don demonstrated the diving equipment and the boat’s dive support system. The oxygen tank can support a diver for 45 to 60 minutes underwater, and two divers can depart from the boat at the same time. This modern diving boat has an air compressor that allows oxygen tank refilling on the boat, so divers can look for mussels for hours without returning to shore to refill the tank. The equipment also supports communication between those on the boat and the diver in the water.

When ready, Don dove into the water. Due to very low visibility, it is not possible to clearly spot the mussels. Divers locate them by using their hands to feel their exposed portions. Experienced divers can determine the species based on the mussel morphology. Multiple dives were made to bring back enough samples of different species, each one taking about 5 to 10 minutes.

At the first sampling spot several dives were made. Almost all the major species of interest to the researchers were collected, except for one called the “bankclimber.” We decided to move to another spot to try to find it. At the second spot we successfully recovered the bankclimber and other mussel species. The mother-of-pearl of the pink heelsplitter shows a very bright and vivid pink color and orient. Don gave the team several quick crash-course lectures on Tennessee River mussel taxonomy and anatomy.

At the end of the day, the group had collected enough shells of five important known pearl-producing species. Back at the riverbank, the GIA pearl research team quickly sorted the shells into different species with Gina's expertise. All mussel shells were sorted by species, placed in labeled plastic bags, and stored in an ice chest to keep them fresh before shipment.

The five species collected were washboard (Megalonaias nervosa), ebony (Fusconaia ebena), pink heelsplitter (Potamilus alatus), purple bankclimber (Elliptoideus sloatianus), and three-ridge (Amblema plicata). Of these the washboard is the most valuable and is used for the limited freshwater pearl culturing in Tennessee today. It has a very thick shell, especially along the hinge, so it is ideal for bead making. During the commercial shell industry’s heyday, washboard was sold for about $4 a pound. Today the price is only about 50 cents. Ebony is the most abundant species in Kentucky Lake. Don estimated that of the total harvest each year by weight, about 50% is ebony, 20% is three-ridge, maple leaf, and pigtoe; and 10%–15% is washboard. All five species can potentially generate natural pearls; therefore genetically characterizing them is critical for the identification of more challenging natural pearls that have structures similar to some non-bead cultured pearls. All five have very distinct appearances that correspond to their names.

All samples were packaged and shipped with dry ice to the institute GIA is working with on the DNA project. The packaging was carried out at a local dry ice company. Big blocks of dry ice were sliced into slabs, wrapped with paper, and placed with the mussel shell samples. Shipping and transporting dry ice involves very strict regulations and can be dangerous. For example, when dry ice is transported in a vehicle, the windows must be rolled down for airflow. Since the sublimation of dry ice releases carbon dioxide, which is heavier than oxygen, it concentrates in the lower space of the car. This concentration can quickly suffocate the people in the vehicle without any warning.

DNA bar coding is a powerful tool for accurate species identification. The technique innovatively combines taxonomy, genetics, and computer science. DNA bar coding of the Tennessee River pearl mussel shells will provide a genetic database for future pearl identification since pearls also contain a small amount of organic residue from the “mother” shell. More research will be carried out on bridging the DNA bar coding technique to pearl identification by GIA’s pearl research team. This will help tremendously with the more challenging cases submitted to GIA around the world.

TENNESSEE’S CURRENT PEARL INDUSTRY

Both the prosperous shell business and pearl culturing gradually came to their ends in the late 1990s and especially after John Latendresse passed away in 2000. The Birdsong Creek pearl farm was then sold to its current owner. Today’s operation includes a pearl museum, an active small-scale pearl farm, a pearl jewelry showroom, a boat dock, and a resort. It remains the only active pearl farm in North America.

The farm’s production is very limited and mainly supplies the on-site shop while at the same time demonstrating pearl farming techniques for the visitors. The impact of, and competition from, China as the main freshwater pearl supplier has drastically reduced the number of freshwater pearl farms in the rest of the world. As a result the commercial shell industry has also been impacted over the past decade. According to Gina, in the height of the industry, there were around 2,000 divers harvesting mussels fulltime. TWRA data shows that in 2013 only 43 mussel diving permits were issued. Today fewer than 20 divers are still actively diving for mussel shells in the state.

The group met a mussel shell buyer in Camden during their trip. Steve Hatley used to work for Gina’s father in the commercial shell industry and is currently the only shell buyer in town. He explained the main process of shell sorting to us and showed the team the shakers and other tools applied to the process. Compared to two decades ago, the price of mussel shell has dropped to only a fraction of its value, putting a lot of people out of business. Gina informed the GIA team that Japan’s demand for mussel shell is still stagnant. She also pointed out that the Japanese have stockpiled enough mussel shells for possibly the next 50 years, and the Chinese use their own shells.

While the diminishing pearl and shell businesses have caused activity in the once-booming town of Camden to decline, it has helped replenish the local mussel population. When asked about the future of the American pearl industry, Gina is very positive. To her the industry is sleeping instead of dying. The breathtaking natural beauty of the pearl and the mother-of-pearl in many mussel shells is undeniable. A break could be positive for this industry that relies on a natural resource that takes time to renew itself.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology at GIA Carlsbad. Dr. Chunhui Zhou is pearls research scientist and manager of pearl identification at GIA New York. Artitaya Homkrajae is staff gemologist at GIA Carlsbad. Joyce Wing Yan Ho and Emiko Yazawa are staff gemologists at GIA New York. Pedro Padua is video producer at GIA Carlsbad.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors would like to thank Gina Latendresse for her assistance in making this trip possible and for sharing her experience and knowledge while in the office and field. They also highly appreciated the guidance and help of Don Hubbs of the Tennessee Wildlife and Resources Agency.