Why are Pink Diamonds Pink?

GIA Researchers Dive Deep into their Crystal Structure

October 21, 2019

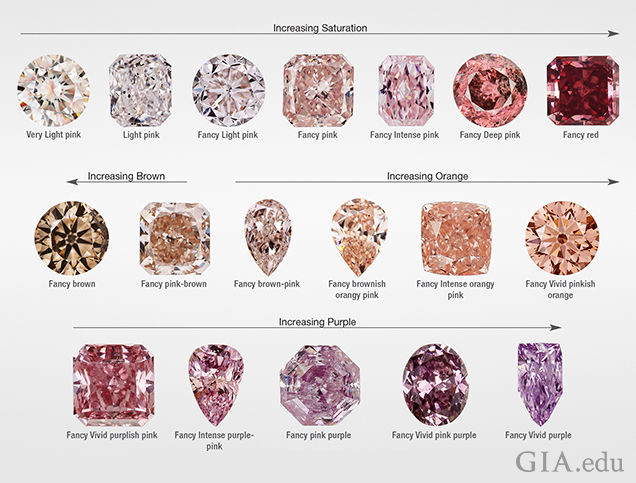

Natural pink diamonds are among the most valuable and rare of Earth’s treasures. Top, vivid-colored stones can bring more than $2 million per carat at major auctions. Such prices come from their rarity as much as their beauty – only a tiny percentage of diamonds have pink color, and only a tiny percentage of these have a rich, vivid color.

Pink diamonds created in a laboratory, however, are quite different from most of their natural counterparts. Manufacturers can’t replicate the way the vast majority of these fancy colored diamonds formed in nature, according to GIA researchers.

Employing GIA’s immense database of more than 90,000 natural pink and related colored diamonds graded between 2008 and 2016, GIA researchers Dr. Sally Eaton-Magaña, senior research scientist; Troy Ardon, research associate; Dr. Karen V. Smit, research scientist; Dr. Christopher M. Breeding, senior research scientist and Dr. James Shigley, distinguished research fellow, produced the most detailed and comprehensive gemological analysis of pink diamonds to date, published in the Winter 2018 edition of the Institute’s quarterly journal, Gems & Gemology.

The sample set of 90,000-plus diamonds includes all those submitted to GIA from 2008 to 2016 with pink as a primary color, and also spans the color hue range from red to purple and saturation range from faint to dark, along with brown diamonds, which share a similar cause of color as pink and related stones. Many of those 90,000 diamonds were small, with low color saturation.

This research confirms that the color of 99.5% of pink diamonds comes from distortion in their crystal structure, not from trace elements, such as nitrogen, which causes yellow color in diamonds or boron, which causes blue. In pink diamonds containing nitrogen, the color is generally concentrated within parallel narrow bands called glide planes, lamellae, or pink/brown graining, depending upon the color. These lines are visible under a microscope and cutters orient them perpendicular to the table to maximize body color.

While many color-producing defects can be introduced through laboratory treatment processes, atomic level distortions in a diamond’s crystal structure created by plastic deformation cannot.

“We know that plastic deformation is associated with the vast majority of diamonds with these colors, but we still do not know the actual atomic structure of the defect causing the color,” says Breeding, who notes that the pink color is caused by a broad absorption band centered at 550 nanometer (nm) in spectroscopic analysis. Spectroscopic analysis is an important gemological tool to measure the impurities and other defects within a diamond (and other gemstones) that give rise to specific absorption peaks or bands in the visible spectrum. The researchers said that there is no known method of replicating plastic deformation with the 550 nm absorption band by a laboratory treatment or growth process.

All fancy colored diamonds submitted to GIA’s grading laboratories are subjected to rigorous analysis to be certain that the colors ‒ and the diamonds themselves ‒ are of natural origin, which makes the GIA database extensively detailed and valuable for research, Shigley said. He added that the team selected a representative sample of 1,000 pink diamonds to examine even more thoroughly for the Gems & Gemology article.

How are Laboratory-Grown Pink Diamonds Created?

There are laboratory-grown pink diamonds in the market, but they are created by three different methods, said Eaton-Magaña.

“The first, and by far the most common, is through irradiating (exposing to radiation) a laboratory-grown diamond that was grown with nitrogen impurities, then subjecting it to moderate temperatures (600°C to 1000°C) afterwards,” she said. “The vast majority of pink and related colors are made using this method.”

This process creates a defect in the crystal lattice (caused by a missing carbon atom adjacent to a nitrogen atom within the lattice) called a nitrogen-vacancy center that is responsible for the color. Eaton-Magaña said a tiny percentage of natural pink diamonds have this nitrogen-vacancy center, which is identifiable by spectroscopic lines at 575 nm and 637 nm.

“These nitrogen-vacancy pinks comprise about one half of one percent of the natural pinks in the GIA database,” she said. They are type IIa diamonds (a rare type of diamond with an exceptionally pure chemical composition: almost all carbon, with negligible amounts of nitrogen or boron) with a very uniform pink color and no visible colored lamellae. These stones are sometimes termed Golconda pinks, but they don’t necessarily have a connection to the Indian mine that closed in the late 18th century.

Generally, she noted, natural nitrogen-vacancy pinks have pale colors, while the laboratory-grown and treated diamonds are more highly colored. Additional testing, such as at a gemological laboratory, is essential to determine the cause of color in such diamonds.

The second method cited by the researchers occurs only in chemical vapor deposition laboratory-grown diamonds (CVD), where a 520 nm spectral band is created during growth that results in an orangy-pink color. GIA has only seen a few of these stones, they say, and the color was not as vibrant as other pink lab-grown diamonds.

The third method, which is even more rare, Eaton-Magaña said, is achieved by adding high amounts of silicon to the CVD growth process which, when exposed to UV illumination, creates reversible color change between the stable pink color and a temporary blue color.

Size and Color Statistics: Are Pink Diamonds Rare?

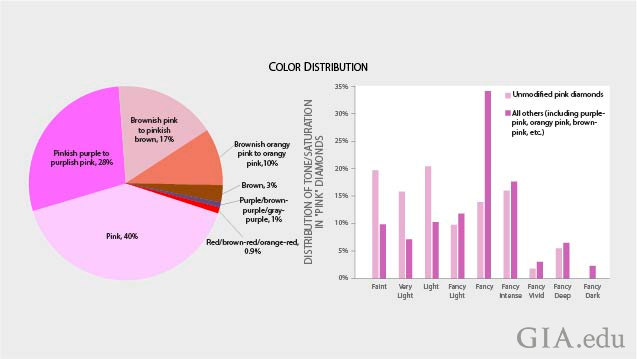

Of the group of diamonds in this study 47% were unmodified (no other color observed) pink; 28% were purplish pink to pinkish purple; 17% were brownish pink to pinkish brown; 10% were brownish orangy-pink to orangy-pink; 3% were brown; 1% were purple-brown, purple-gray and purple; and 0.9% were red, brown-red or orange red. Of the unmodified pink diamonds, 54% were graded faint to light pink.

While brown diamonds are among the most common fancy colors in nature, the low percentage of them in this group suggests that most are sold into the market without grading reports. The brown color is accompanied by other hues, such as pink or yellow, or the brown stones are treated to produce other colors.

The vast majority of the group (83%), weighed less than one carat, with 56% of them being under one-half carat. The dominant shapes were round (24%), pear (20%), rectangle (16%) and cushion (13%).

The research ‒ the most extensive ever carried out on pink and associated colored diamonds ‒ found that 25% are type IIa, which is much higher than with colorless to near-colorless diamonds (where the percentage is < 5%), Breeding said.

The majority of type Ia pink diamonds (diamond containing clusters or aggregates of nitrogen atoms as impurities in the crystal lattice) almost exclusively come from two sources: Australia’s Argyle mine and Russia, which also happen to be the most prolific and consistent producers of such stones. Type IIa pink and other type Ia pink diamonds come from other sources – such as Tanzania, South Africa, and Brazil – but there is no reported regular production from any mine.

“It’s unusual that these types are from very specific locales, especially because they are so rarely found in other sources,” Breeding noted, adding that because Argyle is the dominant source for highly saturated (colored) pink, purplish-pink and red diamonds; the decline in the numbers of such stones will be substantial after the mine closes next year.

Research Aids Automated Detection of Treatment/Lab Growns

This pink diamond study enables GIA to better understand how these rare and beautiful diamonds formed and the properties that give them their color. The researchers found many new details at the atomic level by analyzing the absorption spectroscopy and photoluminescence data. These findings add to the understanding of these amazing stones – which can enable faster, more accurate identification.

The research from this study reinforces GIA’s development of an upgrade for the GIA iD100® gem testing device that adds a function to accurately screen pink and related color diamonds for treatments and synthetics.

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.